BODY SURPLUS - JULIANE REBENTISCH IN CONVERSATION WITH BETTINA ALLAMODA

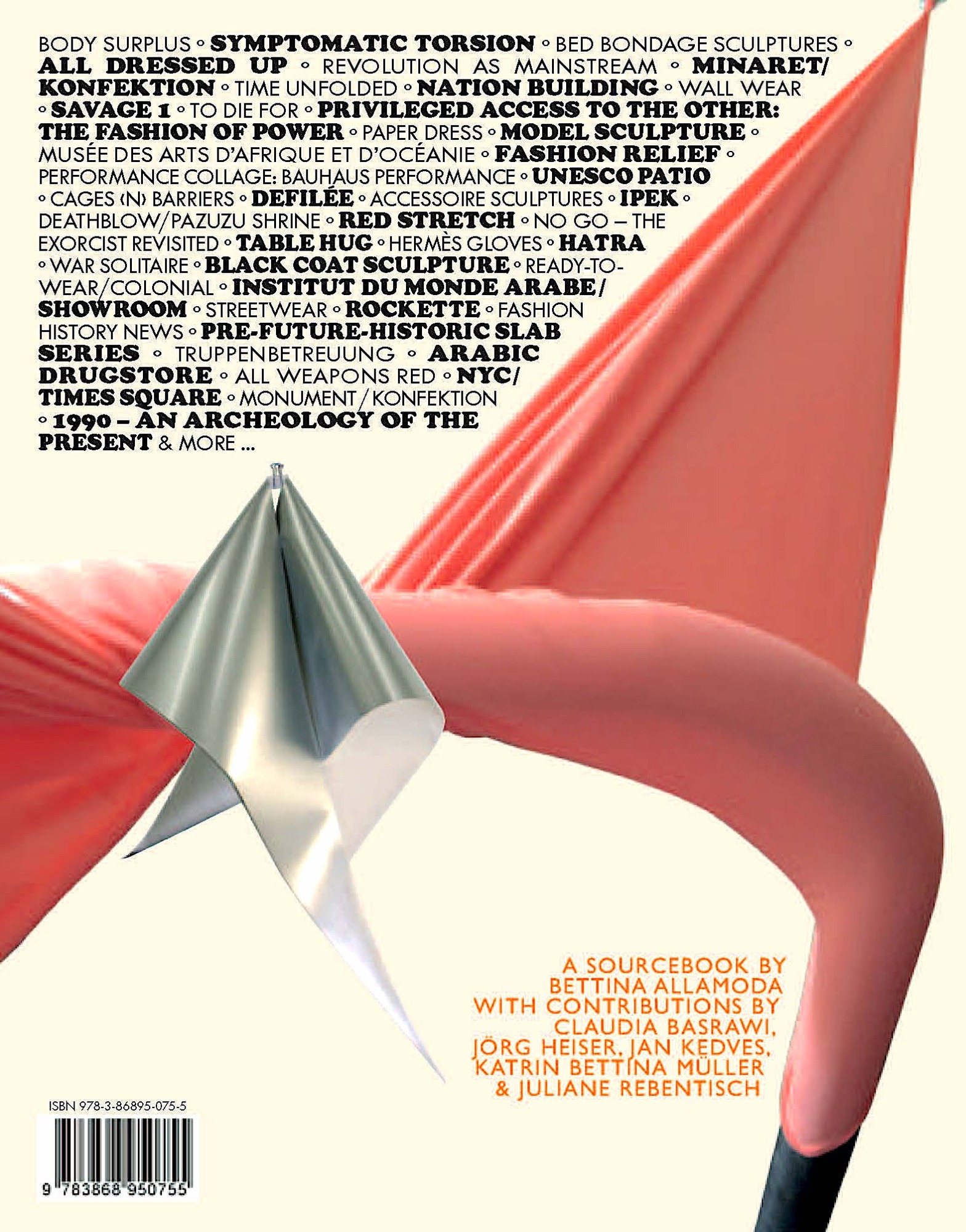

from: Catwalk to History, a Sourcebook by Bettina Allamoda, Revolver Publishing Berlin 2010, in conversation with Juliane Rebentisch & essays by Jan Kedves, Jörg Heiser, Claudia Basrawi & Kartin B. Müller

Bettina Allamoda: I actually have to force myself to handle textiles as a material at all. I have a certain antipathy towards them, especially where sewing is concerned. In Black Coat Sculpture(1), I turned this aversion to productive use for the first time: The fabric for this large-scale work is stretched way past its limits, used for something unsuitable and inappropriate, and pressured into a shape that acts against its very substance.

JR: A love/hate relationship with textiles? In your case, however, the result isn’t the kind of subversive over-affirmation of the association between working with textiles and feminity that is found in Rosemarie Trockel’s work. I’d say that your working method, the way you handle fabric, is distinctly sculptural.

BA: My approach to the material does have to do with sculpture, yes. I like the craft side of it. But that has never been my sole focus. I’ve always been interested in the cultural resonances of any given material, including textiles. Among other things, I refer to the way specific fabrics are used and deployed in fashion, film, and everyday (working) life. And in the cultural significance attached to them – flags being an extreme example.(2) I’m interested in the possibility of giving the material a psychological charge, so putting it under strain always has more than a purely formal significance for me. As I mentioned, Black Coat Sculpture was the first time I used stretch fabric, pulled over a styrofoam base. In the end, it looked more like a bomb, you’d hardly think of it as ordinary clothing fabric. Making this piece was more like upholstery. Rather than sewing the fabric, it was fastened in place with pins. This gave the object as a whole an astonishing firmness, and yet it remained provisional.

JR: Most of your textile sculptures and reliefs relate the stretched fabric to another element: an abstract form, a stand, a heavy iron object. In some cases, completely clad with fabric, in others still partially visible – demonstrating a reversal of prevailing power relationships: a jersey fabric commonly known for its light, accommodating, and yielding qualities is used to hold heavy equipment or heavy objects. In this tension you create, the soft material appears unexpectedly strong. Strained as it is, it not only proves itself amazingly robust, but also ap-pears as the more aggressive part of the constellation: a kind of shackle.

BA: In Monument/Konfektion III, a heavy, coffin-like wooden object is fixed to the wall by stretched jersey fabric. The two sides come together here: the abstract object is veiled, but this veiling has a holding or supporting function. There are also works with bicycle stands, the U-rack kind that also resemble barriers. These pre-fabricated elements are held in place by extremely stretched Lycra, which really turns the tables: here, the soft lingerie fabric carries the steel, itself becoming a barrier. Of course, I’m also interested here in the conflict be-tween the materials, the way they disturb and act on each other. This is also true of other pieces made of actual police barriers or demonstration barrages which I confront with organza.(3)

JR: In terms of content, an element linking your many works with barriers is their indirect reference to the body. Barriers evoke situations where bodies are refused entry or exit, they are instruments of discipline. Barriers in a gallery function as a drastic intervention into the exhibition architecture. But as paths are blocked and movements dictat-ed, attention is of course also focused on the body of the visitor. As a result, the correlation between movement and perception that is fundamental to experiencing sculpture and installations potentially opens up links to real-world contexts established by the barriers in question. Moreover, you combine barriers with textiles that evoke the body in still another way – be it lingerie fabrics that call to mind both sex and sex work, or the rubberized blue stretch cloth recalling hospitals and the clinical handling of disease and frailness, as in Bed Bondage Sculpture #1(4). In both cases, the combination of fabric and steel has a brutal quality that underlines the association of barriers with potentially violent disciplining of bodies. At the same time, in conjunction with the fabrics, the barriers take on another quality that points in an opposite direction. This has to do with the formal inversion of power relations we spoke of earlier. In the case of Bed Bondage Sculpture #1, the barrier comes for moments to resemble the backrest of a tubular steel hospital bed. With sexualized fabric (Bed Bondage Sculpture #2), similar inversions occur, having associations with sadomasochism.

BA: Of course it’s not about illustrating SM. Formally speaking, the Bed Bondage Sculptures(5) deal with bonds, knots, and restraint. Often, they involve bringing together two custom-built readymades, as I like to call hem. It’s never quite certain which element wins in the end, due to the use of fabrics that are hard to identify, hard to grasp, quite literally. The peculiar, shower-curtain-like wash able fabric I used for Bed Bondage Sculpture #1 may have a clinical feel, but it could also be used for something completely different. It’s unclassifiable. That’s something I’m very interested in: versatility. How are things used? How are they repurposed? The way barriers are deployed in urban spaces can be highly diverse. It can have very different meanings.

JR: This interest in versatile modules was already a factor in earlier site-specific work of yours. You worked a great deal with the covering or cladding of spaces, allowing them to take on a different character in the situation. These were temporary interventions, functioning for the period of an exhibition, easily removed and potentially achieving a complete ly different effect elsewhere. As interventions focusing on surface – something just gets covered, with no alteration of the underlying structure – the works highlight their own temporary character. That’s one side. The other is that this superficial intervention is by no means defensive towards the substance of the structure. The superfici-ality is precisely the point. It’s clearly about drawing attention to decor, to what supplements the architecture, so to speak. In structural terms at least, there are links here to the aesthetic of camp. In some cases, you made this explicit in your choice of fabrics.

BA: Through dealing with buildings that have received a different face in the course of history, including a new façade added after German reunification, (6) I began to take an interest in interior design: the possibility of varying spaces by means of textiles from wall fabrics to curtains to carpets (7). This interest focuses both on covering structures entirely and on dramatizing them by means of translucent fabrics. I’m concerned with the staging of spatial elements. I also experiment with extreme fabrics used in stage productions: cheap and simple sequined stretch fabrics, PVC dance floor material, or high-quality velvet carpets that are not necessarily suited for everyday use on account of their garish colors. I made a glittering dress for a wall, for example. And some of the stretch reliefs were inspired by poses and gestures performed on stage by Liberace’s Rockettes (8).

JR: Aside from your interest in the performance of spaces, you’re also interested in performances that happen in specific spaces. I’m thinking, for example, of your work on Paris fashion shows.

BA: Initially, this body of work (ready-to-wear/colonial) came out of a preoccupation with appearance, performance, and display. Over a six-month period in Paris, I visited various prêt-à-porter, haute couture, and menswear shows. I was interested in the interplay of the various elements: What space is chosen? Venues included the Musée des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie (the only remaining pavilion of the 1931 Exposition Coloniale Internationale), the UNESCO building, or the Institut du Monde Arabe. What spatial order is established by the event architecture, where is the audience positioned, where are the photographers? How does the performance work, the movement of models in the space? Viennese fashion designers Wendy & Jim had a show at the Institut du Monde Arabe where a model not clearly identifiable as male or female strode down the main hall wrapped in a black cloth. This venue is used for very different purposes. Perfume presentations and fashion shows take place there, occasionally it’s used as a showroom, but it is also used for meetings by the Gulf Cooperation Council. Such overlapping is the starting point for my research: Do the dress codes and fashions of the recent past function as a kind of “nation building”? In my work on the Institut du Monde Arabe, the post-colonial dimension plays a key role, as well as a concern with the politics of surface, of representation. I was especially intrigued by the ambivalence of this model, as it made clear the way fashion appropriates codes and somehow empties them. Here, the meaning of veiling remained totally free-floating. This was one source of inspiration for Black Coat Sculpture.

JR: Do you have a concept for finding your materials? I don’t mean the textiles, but the subject matter from (pop) culture and recent history which you reference in your work? It seems to me these are quite often stories where there’s no clear distinction, from the outset, between reality and fiction. Cases, then, where this distinction, that is often called into question by the way history is dealt with in artworks themselves, is already unstable in the source material.

BA: In my research, I’m basically interested in the way history is mediated. What do people lose interest in at a given moment, when do they become interested again? Why do specific historical events move in and out of the spotlight like this, as in fashion? The topics or news items that interest me are mostly ones that initially appear absurd or completely fictitious. On the one hand, it’s about questioning particular forms of documentation, the archive and it’s history, but also about a certain aspect of re-reading, investigating, “excavating” – about questioning the creation of hierarchies for news and stories, as performed by historiography.

JR: But you’re not concerned with contrasting these constructions of history with more truthful versions, or claiming the right to a counter-history. You’re not an investigative journalist. Instead, your works are more about accentuating the construction of what we consider to be reality, keeping the construction in abeyance. Hence your emphasis on the fictitious. Does this not also relate to your special interest in science fiction?

BA: In a series of works around the theme Science Fiction/Science Fact, I was indeed intrigued by the complex and contradictory relation of fact and fiction (9). The works took as their point of departure the Soviet cosmos. Space is an extraordinary field for the projection of the most diverse ideologies and world views, as manifested both in historical documents and in works of fiction, films, etc. But rather than finding and pursuing particularly obscure stories, the idea was to start by rediscovering the various views of space itself. I was interested not only in the stories, but also in film sets and the ways these utopian world views materialize into objects. Here, my work was more like that of an archaeologist, excavating these objects in which past visions of the future took on concrete form, and exposing them to debate again in a new installation.

JR: This interest in the insecure boundary be-tween fiction and reality is also behind your performance lectures. As the term suggests, this format oscillates between scientific lecture and performance. To the uncertainty in the relation between scientific claim to truth and artistic fiction is added an uncertainty regarding the status of your persona. It is left open whether you are performing as an artist with a knowledge of cultural studies, or as a scholar in the field of cultural studies with a talent for performance.

BA: My first performance was a performance lecture. I recited news items gathered from archives – not just academic material, but also information from tabloids and popular science news. Based on these selected historical documents, I compiled a lecture narrative that was illustrated with slides and accompanied by music. Besides this collage of news, music, and images, performing itself was an important element, my physical presence as part of this spatial collage. I wore an unspectacular white sequined dress that served as a projection surface for the slideshow. Of course, there was a slightly showy dimension to this. There’s a precedent that I like to mention: The IBM Pavilion at the 1964–65 World’s Fair in New York gave a gala showcasing the first computer, hosted by a woman, not in a sequined dress, but in an evening gown, and a man in a tuxedo. I’m interested in this showcasing of material. The model is a particular type of popular-science multivision event that sometimes has an element of show. But it also has a lot to do with media, with television, and with women as a medium in this context. Later I abstracted from this, so to speak, I recited no text and was now purely the projection surface for a film: the figure in an evening gown interacting with the image. This was not performance in the narrow sense of the word, it has little to do with theater, but it is still about presentation. Later, this was recorded without an audience and re-projected as a video installation. The live performance was omitted in favor of addressing the question of how moving images are presented in space.

JR: So, and this is what seems important to me in what you just said, your engagement with performance also derives from an engagement with space. There’s a link to your sculptural work.

BA: The important thing for me here is immediacy: an audience being directly present and a body, in this case mine, being posi-tioned in the space. This is related both to sculpture and to bands playing a gig. The element of stage appearance is also important to me.JR: your performances are clearly distinct from the performance tradition in feminist art with its excessive corporeality and drastic exposure of the body. your work draws instead on specific show formats, you never expose your body as such.

BA: The sequined dress is especially important here, the sequined data-dress. I got it in a thrift shop. It doesn’t really fit me, it’s more like a nightgown. It glitters, it’s a “lovely dress,” but basically it’s at odds with the body.

JR: This is an important point, that it doesn’t fit, that a dissonance exists between body and dress. It introduces an ironic distance towards the cultural expectation on women to expose themselves in their physicality, an expectation whose violent side so many female artists in the seventies unmasked in performances based more on overstatement. This dimension of self-torture is largely absent in your work. It’s more about an investigation of show formats, even comedy formats, whose formal qualities you isolate. It’s never directly about you or your body. It remains an act, a show, precisely to the extent that the distance between you and what you are showing remains clear. One can absolutely sense your enjoyment of performing, of the show.

BA: I grew up with that. All those comedy shows, game shows, and performances were part of everyday life in Canada. There were variety shows at school. As well as playing ball in the street, we actually re-enacted comedy shows. So for me, performing came naturally. Kids just did that there in the 1970s. It was the Sesame Street approach without fixed genders: there were show-masters, vampires, fluffy green frogs, a blue cookie monster. It was all-inclusive. This has remained crucial to my performances – the mingling of high and low with aspects of lecture culture, be it from movies, television, or music. The psychedelic moments in popular science multimedia presentations were also important to me. And initially, it really was aimed against the feminist performance tradition and that whole “I live my body” culture. I’m certainly not the first person to have challenged that with humor. But in my work, there’s also the focus on mass culture and popular science: a deep interest in pop. Ultimately, it was this interest in show business and its glitzy outfits that prompted me to pick up textiles as a material, despite my initial reservations.

JR: This is something I find increasingly intriguing, the way you keep emphasizing taking things in hand, working with the material in this immediate way, if you will. your work often has a craft dimension, and I think that’s something worth elaborating on. you insist on craft, on an old-style approach to sculpture in fields where the hand-made no longer plays a role, or where it can at least no longer be taken for granted. When dealing with information, there’s no actual need to print things out and hang them up, as if it was about banging a nail into a wall. There’s a built-in disconnect between your material and the way you present it. It seems to me that for you, rather than production value, the crucial category is this getting to grips and taking things in hand. Even in sculpture, this can no longer be taken for granted. Art production has long ceased to be the opposite of industrial production. your own work often includes elements that you’ve had industrially manufactured. But then you process them further by hand. This is clearly not about rein-stating the old image of the sculptor. It’s more a matter of insisting on the physical dimension of your production processes.

BA: yes, that’s exactly right. It also has to do with appropriating materials and techniques – I often do things I’ve never done before. I have some craft training, but I’m not into mastery, not interested in craft as in classic sculpture. I never placed myself in a craft tradition. I’m interested in production processes in general, how things are made and which norms are involved. This means observing the production of elements I have manufactured, but also attempting to appropriate certain skills. Not a total do-it-yourself approach, that would be just another specific field with its own restrictive aesthetic. And it’s not about expression either.JR: No, not the sacrosanct earnest of subjective expression. Instead, what I see here is, once again, a slightly ironic insistence: using your body as a somehow unwieldy element, the individual’s capacity for physical work as something imperfect, unfitting.

BA: There is also an actionist element.JR: yes, but without heroic pathos. More a laconic, causal moment of disruption.BA: It’s not about focusing attention on a lack of power.

JR: Precisely. The body appears more as something unresolved, like an anachronism that persists. By this I mean not just the body beneath an ill-fitting dress, but also the abstract body trace, the trace of physical work in your sculptures. They have an explicitly imperfect look that highlights the hands-on side of their production. The body insists – especially in this strange lack of place, that is to say: to the extent that the body itself is not directly the subject – opposing the sur-faces, remaining present as that which they don’t absorb. It’s simply still there, like a supplement: X + body.

1. See Nation Building/Wall Wear, 2009 and Intitut du Monde Arabe/Nation Building (ready-to-wear/colonial III), 2004. 2. See ibid. and the video Fashion History News, 2003. Fashion History News combines catwalk “radical chic” and fashion photography with images of demonstrations and political violence almost unnoticed, sampled from found and own footage in current news media.

3. See Streetwear, part of a sculpture series for To Die For, 2008, conceived for and with Nikolaus Utermöhlen’s work An Infinite Painting on “A Vision of the Last Judgment” by William Blake at September, Berlin, 2008.

4 & 5. Bed Bondage Sculptures, series, part of No Go – The Exorcist Revisited, 2010.

6. See former House of Soviet Science and Culture in Berlin Mitte (1990 – eine Archäologie der Gegenwart, 1992); Haus des Lehrers (House of the Teacher) on Alexanderplatz, Berlin (ambi: in/out project, 1999, Model Map: Zur Karthographie einer Architektur Haus des Lehrers Berlin, exhibition project and publication, 2002/05); the first Bauhaus model home (Versuchshaus am Horn), Weimar (Performance Collage: Bauhaus Performance, Bauhaus-as-readymade, both 1999).

7. See les artistes décorateurs, 1996/99, a body of work and publication on the interface between autonomous art, commissioned work, and representative design. For this project, sculptures and installations were made using the material of a “decommissioned” exhibition display from the former GDR Carl Zeiss Optical Museum in Jena, Thuringia.

8. See To Die For, 2008.

9. See 1990 – eine Archäologie der Gegenwart,1992, or Toy, Cult & Aerospace, a multi-vision-installation, part of the site-specific work Memorabilia, Science & Fiction 93 at Zeiss-Großplanetarium, Berlin, 1993.