Stephan Balkenhol

28 Nov - 24 Dec 2008

STEPHAN BALKENHOL

Slivers of wood and the rough treatment of the coarse material are fingerprints of a seemingly violent production process, in which the sculptures – in the form of reliefs, figures, busts and heads of people – were peeled out from a rigid block of wood. The sculptures hover in a state of being unfinished, in the continuum between being a drawing and the final object ready for being exhibited. It is exactly this imperfect state which has the potential to reanimate the dead material, to instill life into it.

But Balkenhol’s artistic merit reaches beyond his distinctive treatment of the material. His uniqueness among contemporary sculptors is certainly his nostalgic relationship to classicism and his devotion to the human body, which he rediscovered in the 1980s – a time which was dominated by abstract forms, in which glamorous objects rather than human bodies prevailed the artistic scene, and in which the appraisal of the human figure was still imbued with negative connotations in respect to fascistic monumentalism and heroism. Yet, Balkenhol was courageous enough not to meet the expectations of his contemporaries, to interrogate the experimental and to reintroduce the human figure.

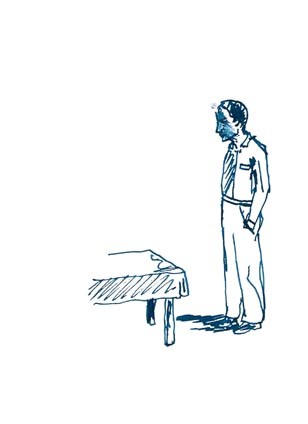

Balkenhol’s works dare to be simple and rather mundane, with a touch of pop art. His statues are self-referential; they merely represent themselves as there are not hidden depths, secret stories and anecdotes, which have to be revealed by the spectator. Balkenhol does not attempt to comment on socio-political issues, nor does he create identifiable individuals of a particular personality or social class but his people are common people – people that surround us in our everyday lives. This sheer and blatant normality is conveyed through the unspectacular clothes the characters wear and their reserved, unobtrusive poses. Their facial expressions are emotionless. All too often, they are compared by critics to people who are recovering from a severe illness and are in a process of re-civilisation.

This inaccessibility of individuality is intentional: If one attempts to find clues for interpretation in the titles, one will be disappointed: Mostly, they are plainly labelled “big man with green shirt” or simply “head”.

Still, Balkenhol’s prolific output lends itself to difficult readings and interpretations, despite its simplicity – this is what causes confusion. As a spectator, we are captured by the tension between identification and alienation. It is precisely the characters’ lack of identity and personality that invites us to identify with the common man or woman: The sculptures function as a mirror of our basic human selves. But simultaneously, this familiarity and humanity is called into question by dint of their representation as either larger or smaller than life size. One is left wondering.

Slivers of wood and the rough treatment of the coarse material are fingerprints of a seemingly violent production process, in which the sculptures – in the form of reliefs, figures, busts and heads of people – were peeled out from a rigid block of wood. The sculptures hover in a state of being unfinished, in the continuum between being a drawing and the final object ready for being exhibited. It is exactly this imperfect state which has the potential to reanimate the dead material, to instill life into it.

But Balkenhol’s artistic merit reaches beyond his distinctive treatment of the material. His uniqueness among contemporary sculptors is certainly his nostalgic relationship to classicism and his devotion to the human body, which he rediscovered in the 1980s – a time which was dominated by abstract forms, in which glamorous objects rather than human bodies prevailed the artistic scene, and in which the appraisal of the human figure was still imbued with negative connotations in respect to fascistic monumentalism and heroism. Yet, Balkenhol was courageous enough not to meet the expectations of his contemporaries, to interrogate the experimental and to reintroduce the human figure.

Balkenhol’s works dare to be simple and rather mundane, with a touch of pop art. His statues are self-referential; they merely represent themselves as there are not hidden depths, secret stories and anecdotes, which have to be revealed by the spectator. Balkenhol does not attempt to comment on socio-political issues, nor does he create identifiable individuals of a particular personality or social class but his people are common people – people that surround us in our everyday lives. This sheer and blatant normality is conveyed through the unspectacular clothes the characters wear and their reserved, unobtrusive poses. Their facial expressions are emotionless. All too often, they are compared by critics to people who are recovering from a severe illness and are in a process of re-civilisation.

This inaccessibility of individuality is intentional: If one attempts to find clues for interpretation in the titles, one will be disappointed: Mostly, they are plainly labelled “big man with green shirt” or simply “head”.

Still, Balkenhol’s prolific output lends itself to difficult readings and interpretations, despite its simplicity – this is what causes confusion. As a spectator, we are captured by the tension between identification and alienation. It is precisely the characters’ lack of identity and personality that invites us to identify with the common man or woman: The sculptures function as a mirror of our basic human selves. But simultaneously, this familiarity and humanity is called into question by dint of their representation as either larger or smaller than life size. One is left wondering.