David Schutter

02 May - 27 Jun 2015

DAVID SCHUTTER

Glove in Hand

2 May - 27 June 15

Berlin – “Glove in Hand” is the American artist David Schutter‘s (b. 1974) third solo show at Aurel Scheibler. It features paintings and will run through June 27, 2015

You are warmly invited to the opening of the exhibition on Friday, May 1 from 7 until 9 pm.

The 11th day. The king’s slaves carried me in a hammock to the Congo River, which was over two long miles away. On arriving there, I could see from atop a hill our ship lying at the hook of the Padron. I hired a prauw for two ells of blue cloth to bring me across the river.

Pieter Van Den Broeke, Chief Tradesman and Admiral of the Dutch East India Company, from his journal “Third Voyage to Angola”, 1612

Pieter Van Den Broeke brought 65,000 lbs. of ivory to Amsterdam a year before the above was written and was soon thereafter given his ultimate title. Later placed to govern trade in the Banda Islands by his corporation, Van Den Broeke so harshly decimated the native population and competitive traders in his pursuance of a nutmeg and clove monopoly that the islands had to be repopulated in order to sustain the rate of export.

Between the 1630s and the 1650s, Frans Hals painted Van Den Broeke and his contemporaries from Rotterdam and Haarlem. These 1% elite formed an early venture capital group that invested in the Dutch East India Company and supported its colonial project. As the new rich, these former sailors and merchants, brewers and burghers, sought a portraiture fitting of their narrative grounded in simple beginnings. Frans Hals’ open brushwork was referred to in the marketplace as painting in the “rough manner”. Reminiscent of the popular Flemish paintings much in vogue by Antony can Dyck and Peter Paul Rubens, Hals’ “rough manner” was alluring as a stylistic metaphor with these rugged capitalists would commission an image of self-made men newly familiar with with culture and refinement while at once latently disclosing a mastery of labor and power.

Persistent forms of 17th Century Dutch painting bear incumbent significance on how the syntax of painterliness is repeatedly defined by the descriptive touch of the painter’s hand. Through deft brush-play and a keenly observant eye for character, Frans Hals’ portraits evoke an instantaneity that seemingly belies the affectations of representation in the portrait genre. The athletic alacrity of his brush was a kind of naturalism that spoke to an illusory perfection, a fit to fidelity like the popular idiom “hand in glove”. However, his signature stroke was an aggregate of market forces steered by the commissioning class of new colonial power that through their influence of wealth held glove in hand.

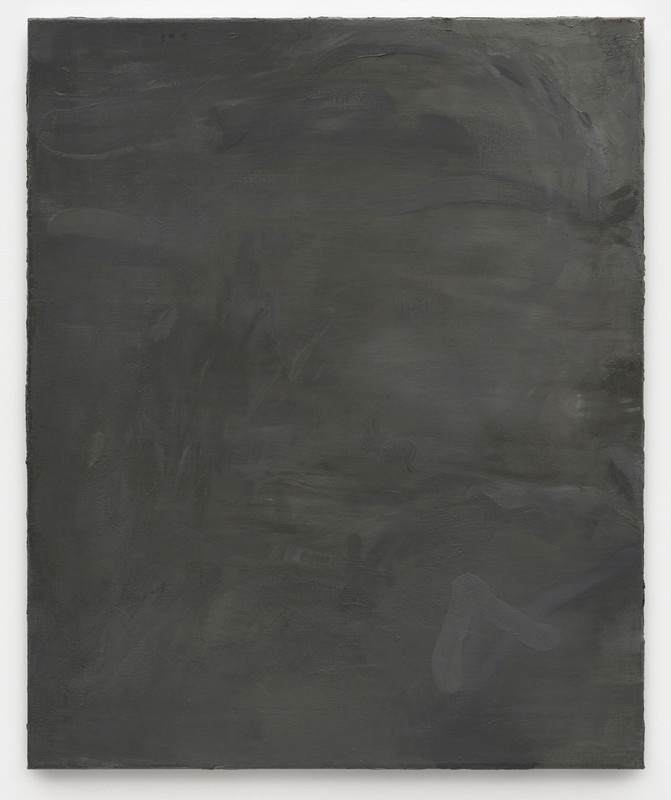

In a suite of five paintings, the American artist David Schutter sources five portraits by Frans Hals representative of the above group that he studied firsthand in British and American collections, including a portrait of Van Den Broeke. Schutter has “re-made” these source subjects in a 1-to-1 scale with like materials and without aide memoires, resulting in objects of inquiry that are both familiar and estranged. Less a test of memory, Schutter’ practice is more a phenomenological study that discusses the distances and problems encountered when making a painting. The works in the exhibition are as much performative re-enactments of the sources as they are discreet paintings, and as such form a painter’s repertory of extended rehearsals that ruminate on the disturbing recurrence of form over content.

The investigations of David Schutter are not homage, but instead are a way toward understanding the continued expectations that paintings function along historical values. In his approach to his subjects, Schutter locates his practice within the traditions of philosophical inquiry by beginning with the surfaces of things. His questions elicit responses to how we re-stratify our knowledge of the past while developing representations of the present, how we can uncover circumscribed categories and make new knowledge from the experience, and how repeated questions come to be ultimately forms of description in a world where the past is often a difficult and arguable anteriority.

Glove in Hand

2 May - 27 June 15

Berlin – “Glove in Hand” is the American artist David Schutter‘s (b. 1974) third solo show at Aurel Scheibler. It features paintings and will run through June 27, 2015

You are warmly invited to the opening of the exhibition on Friday, May 1 from 7 until 9 pm.

The 11th day. The king’s slaves carried me in a hammock to the Congo River, which was over two long miles away. On arriving there, I could see from atop a hill our ship lying at the hook of the Padron. I hired a prauw for two ells of blue cloth to bring me across the river.

Pieter Van Den Broeke, Chief Tradesman and Admiral of the Dutch East India Company, from his journal “Third Voyage to Angola”, 1612

Pieter Van Den Broeke brought 65,000 lbs. of ivory to Amsterdam a year before the above was written and was soon thereafter given his ultimate title. Later placed to govern trade in the Banda Islands by his corporation, Van Den Broeke so harshly decimated the native population and competitive traders in his pursuance of a nutmeg and clove monopoly that the islands had to be repopulated in order to sustain the rate of export.

Between the 1630s and the 1650s, Frans Hals painted Van Den Broeke and his contemporaries from Rotterdam and Haarlem. These 1% elite formed an early venture capital group that invested in the Dutch East India Company and supported its colonial project. As the new rich, these former sailors and merchants, brewers and burghers, sought a portraiture fitting of their narrative grounded in simple beginnings. Frans Hals’ open brushwork was referred to in the marketplace as painting in the “rough manner”. Reminiscent of the popular Flemish paintings much in vogue by Antony can Dyck and Peter Paul Rubens, Hals’ “rough manner” was alluring as a stylistic metaphor with these rugged capitalists would commission an image of self-made men newly familiar with with culture and refinement while at once latently disclosing a mastery of labor and power.

Persistent forms of 17th Century Dutch painting bear incumbent significance on how the syntax of painterliness is repeatedly defined by the descriptive touch of the painter’s hand. Through deft brush-play and a keenly observant eye for character, Frans Hals’ portraits evoke an instantaneity that seemingly belies the affectations of representation in the portrait genre. The athletic alacrity of his brush was a kind of naturalism that spoke to an illusory perfection, a fit to fidelity like the popular idiom “hand in glove”. However, his signature stroke was an aggregate of market forces steered by the commissioning class of new colonial power that through their influence of wealth held glove in hand.

In a suite of five paintings, the American artist David Schutter sources five portraits by Frans Hals representative of the above group that he studied firsthand in British and American collections, including a portrait of Van Den Broeke. Schutter has “re-made” these source subjects in a 1-to-1 scale with like materials and without aide memoires, resulting in objects of inquiry that are both familiar and estranged. Less a test of memory, Schutter’ practice is more a phenomenological study that discusses the distances and problems encountered when making a painting. The works in the exhibition are as much performative re-enactments of the sources as they are discreet paintings, and as such form a painter’s repertory of extended rehearsals that ruminate on the disturbing recurrence of form over content.

The investigations of David Schutter are not homage, but instead are a way toward understanding the continued expectations that paintings function along historical values. In his approach to his subjects, Schutter locates his practice within the traditions of philosophical inquiry by beginning with the surfaces of things. His questions elicit responses to how we re-stratify our knowledge of the past while developing representations of the present, how we can uncover circumscribed categories and make new knowledge from the experience, and how repeated questions come to be ultimately forms of description in a world where the past is often a difficult and arguable anteriority.