Lubaina Himid

The truth is never watertight

08 Sep - 26 Nov 2017

LUBAINA HIMID

The Truth is Never Watertight

8 September - 26 November 2017

Curated by Anja Casser

Badischer Kunstverein is delighted to present the first survey exhibition by British artist Lubaina Himid in Germany. As an artist, writer, and teacher, Himid has dedicated her work to the representation of the black body in art and its debates, while questioning Western stereotypes and classifications. She was one of the first activists in the Black Arts Movement in the 1980s and 1990s and curated a number of significant exhibitions of black female artists. The truth is never watertight brings together a wide range of paintings from the 1980s to the present day, as well as cut-outs, painted wooden objects, and works on paper. The exhibition also focuses on archival material from the artist’s own collection, including catalogues and images by and of black artists from the 1980s and early 1990s. A first extensive publication on Lubaina Himids work will be published in cooperation with Modern Art Oxford, Spike Island (Bristol), and Nottingham Contemporary. Lubaina Himid has recently been nominated for the 2017 Turner Prize.

Early on in her practice, Himid chose painting as her medium, which allowed her to deconstruct the Western myth of “Africa”. To “make the black presence visible” is a central motif running through all the works selected for the Kunstverein’s exhibition. Himid’s approach to painting is not only planar, however, for it also moves into the exhibition setting through painted found objects or figures made from wood and then coloured: so-called cut-outs. Some of these cut-outs from the series Vernets Studio (1994) will be seen again for the first time in this exhibition, challenging collective memory and the codification of art-historical facts. Himid studied theatre design in the 1970s, and her interest in spatial orchestrations led to stage-like compositions in and outside of her paintings; or, as the artist herself states, it also channels “a desire to have art in the room, present, in the moment and not distant and framed within a rectangle.” Furthermore theatre opened up opportunities for political thought and action, first in real street settings and then in the imaginary spaces of her artwork.

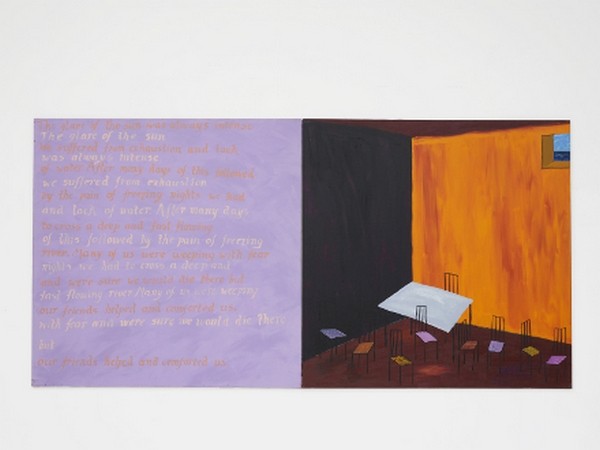

Himid’s painting is at once seductive and provocative. Her pictures are mostly figurative, imbued with brilliant colour and immediate presence. Flight and migration are main topics, as are questions of identity and origin, but also the loss of collective knowledge. Striking patterns on textiles, walls, and tiles are found in many representations, developing their own language (“speaking clothes”) and harking back to the influence of African, European, or Islamic ornamentation. A series of Kangas (2008–12) painted on paper, for instance, references the conventional patterns and motifs of a traditional East African garment, supplemented here with texts by the artist dealing with peril and the will to survive. This atmosphere between harmony and dissonance is characteristic for Lubaina Himid’s works. It is often only at second glance that a reality marked by gender and racial oppression or colonial trauma is visualised. This is the case, for example, in her current series Le Rodeur (2016–17), in which people who are quite elegantly clad meet in bright yet surreal rooms, their rigid posture already hinting at a sense of alienation and unease. In fact, details in the images and the title refer to an incident in 1819 on a slave ship, where all the enslaved passengers and most of the crew contracted an eye infection and went blind. In motifs from the series Plan B (1999/2000), in turn, the painted empty rooms are strangely indeterminate and could be places of refuge or also captivity. Finally, in the impressive installation Drowned Orchard: Secret Boatyard (2015), sixteen painted wooden panels are leaning against the wall, fanning out into the space at ever-increasing angles. The painted motifs of shells, fish, flags, or boats embrace the most different places and cultures. The symbolism of the sea—a frequently recurring motif—alludes to the mobility of humans, but also to lost sites and the dangers of the ocean depths.

Since 2007 Lubaina Himid has been researching the visual and textual presence of black persons in the British dailies. She has noted that the reports subvert, subtly and continually, the identity of the people rendered, and that the ever-rare renderings of black personalities —except in a football or rugby context—are often only used to fill a gap or to enrich a narrative. With the aim of pointing out this inappropriate treatment, Himid has painted select pages from the newspaper The Guardian with traditional or newly created East African patterns and forms. The exhibition presents a comprehensive selection from this sequential work series called Negative Positives (2007–16).

The truth is never watertight refers to a quote by Walter Benjamin speaking about the fact that much of what we expect to find in truth is actually slipping through the net. Himid’s interest focuses on precisely these untight areas in the conveyance of purported truths. Her work is devoted to a critical questioning of codified forms and thus opens the gaze to a vocabulary well beyond Western historiography.

Lubaina Himid (*1954 in Zanzibar, Tanzania) is Professor of Contemporary Art at the University of Central Lancashire. During the past 30 years she has exhibited widely, both in Britain and internationally, e.g. Spike Island, Bristol (solo); Modern Art Oxford (solo); Folkstone Triennale, UK; Nottingham Contemporary (group); Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (group); 14. Istanbul Biennale; Gwangju Biennale; Tate Britain, London; Tate St. Ives, Transmission Gallery Glasgow and Chisenhale Gallery, London.

Himid’s work can be found in public collections including Tate, the Victoria & Albert Museum, The Whitworth Art gallery, Arts Council England, Manchester Art Gallery, The International Slavery MuseumLiverpool, The Walker Art Gallery, Birmingham City Art Gallery, Bolton Art Gallery, New Hall Cambridge and the Harris Museum and Art Gallery Preston.

The Truth is Never Watertight

8 September - 26 November 2017

Curated by Anja Casser

Badischer Kunstverein is delighted to present the first survey exhibition by British artist Lubaina Himid in Germany. As an artist, writer, and teacher, Himid has dedicated her work to the representation of the black body in art and its debates, while questioning Western stereotypes and classifications. She was one of the first activists in the Black Arts Movement in the 1980s and 1990s and curated a number of significant exhibitions of black female artists. The truth is never watertight brings together a wide range of paintings from the 1980s to the present day, as well as cut-outs, painted wooden objects, and works on paper. The exhibition also focuses on archival material from the artist’s own collection, including catalogues and images by and of black artists from the 1980s and early 1990s. A first extensive publication on Lubaina Himids work will be published in cooperation with Modern Art Oxford, Spike Island (Bristol), and Nottingham Contemporary. Lubaina Himid has recently been nominated for the 2017 Turner Prize.

Early on in her practice, Himid chose painting as her medium, which allowed her to deconstruct the Western myth of “Africa”. To “make the black presence visible” is a central motif running through all the works selected for the Kunstverein’s exhibition. Himid’s approach to painting is not only planar, however, for it also moves into the exhibition setting through painted found objects or figures made from wood and then coloured: so-called cut-outs. Some of these cut-outs from the series Vernets Studio (1994) will be seen again for the first time in this exhibition, challenging collective memory and the codification of art-historical facts. Himid studied theatre design in the 1970s, and her interest in spatial orchestrations led to stage-like compositions in and outside of her paintings; or, as the artist herself states, it also channels “a desire to have art in the room, present, in the moment and not distant and framed within a rectangle.” Furthermore theatre opened up opportunities for political thought and action, first in real street settings and then in the imaginary spaces of her artwork.

Himid’s painting is at once seductive and provocative. Her pictures are mostly figurative, imbued with brilliant colour and immediate presence. Flight and migration are main topics, as are questions of identity and origin, but also the loss of collective knowledge. Striking patterns on textiles, walls, and tiles are found in many representations, developing their own language (“speaking clothes”) and harking back to the influence of African, European, or Islamic ornamentation. A series of Kangas (2008–12) painted on paper, for instance, references the conventional patterns and motifs of a traditional East African garment, supplemented here with texts by the artist dealing with peril and the will to survive. This atmosphere between harmony and dissonance is characteristic for Lubaina Himid’s works. It is often only at second glance that a reality marked by gender and racial oppression or colonial trauma is visualised. This is the case, for example, in her current series Le Rodeur (2016–17), in which people who are quite elegantly clad meet in bright yet surreal rooms, their rigid posture already hinting at a sense of alienation and unease. In fact, details in the images and the title refer to an incident in 1819 on a slave ship, where all the enslaved passengers and most of the crew contracted an eye infection and went blind. In motifs from the series Plan B (1999/2000), in turn, the painted empty rooms are strangely indeterminate and could be places of refuge or also captivity. Finally, in the impressive installation Drowned Orchard: Secret Boatyard (2015), sixteen painted wooden panels are leaning against the wall, fanning out into the space at ever-increasing angles. The painted motifs of shells, fish, flags, or boats embrace the most different places and cultures. The symbolism of the sea—a frequently recurring motif—alludes to the mobility of humans, but also to lost sites and the dangers of the ocean depths.

Since 2007 Lubaina Himid has been researching the visual and textual presence of black persons in the British dailies. She has noted that the reports subvert, subtly and continually, the identity of the people rendered, and that the ever-rare renderings of black personalities —except in a football or rugby context—are often only used to fill a gap or to enrich a narrative. With the aim of pointing out this inappropriate treatment, Himid has painted select pages from the newspaper The Guardian with traditional or newly created East African patterns and forms. The exhibition presents a comprehensive selection from this sequential work series called Negative Positives (2007–16).

The truth is never watertight refers to a quote by Walter Benjamin speaking about the fact that much of what we expect to find in truth is actually slipping through the net. Himid’s interest focuses on precisely these untight areas in the conveyance of purported truths. Her work is devoted to a critical questioning of codified forms and thus opens the gaze to a vocabulary well beyond Western historiography.

Lubaina Himid (*1954 in Zanzibar, Tanzania) is Professor of Contemporary Art at the University of Central Lancashire. During the past 30 years she has exhibited widely, both in Britain and internationally, e.g. Spike Island, Bristol (solo); Modern Art Oxford (solo); Folkstone Triennale, UK; Nottingham Contemporary (group); Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (group); 14. Istanbul Biennale; Gwangju Biennale; Tate Britain, London; Tate St. Ives, Transmission Gallery Glasgow and Chisenhale Gallery, London.

Himid’s work can be found in public collections including Tate, the Victoria & Albert Museum, The Whitworth Art gallery, Arts Council England, Manchester Art Gallery, The International Slavery MuseumLiverpool, The Walker Art Gallery, Birmingham City Art Gallery, Bolton Art Gallery, New Hall Cambridge and the Harris Museum and Art Gallery Preston.