Christopher Orr

20 Apr - 30 Jun 2013

CHRISTOPHER ORR

Light Shining Darkly

20 April - 30 June 2013

Kunsthaus Baselland is very pleased to present the first institutional solo exhibition of the British artist Christopher Orr (born 1967 in Scotland, lives and works in London). The exhibition presents a series of works from recent years supplemented by new works created specifically for the exhibition.

Orr belongs to the most impressive among contemporary painters. His works have been shown, inter alia, at the 54th Venice Biennale in the Palazzo Zenobio, the CAPC Musée d’Art Contemporain, Bordeaux, the Kunsthalle Brandts in Odense at the Tate Britain, as well as regularly in the galleries of Hauser & Wirth and IBID Projects.

As the title “Light Shining Darkly” already evokes, Orr’s paintings show locations and scenes where something seemingly mystical, supernatural, dark or sinister happens, or you, as the viewer, presage something like this may happen. The landscape scenes in which protagonists act are characterised by special lighting effects. Sometimes a night landscape with an incoming, diffuse cone of light reveals strollers (Descent, 2004), sometimes people stand in front of a rocky slope (Silent One, 2010), or inexplicable scenes take place in a forest in the dead of night (The Silence of Afterwards, 2010 ). Time and again it is the specific use of lighting effects, which at first glance give the motifs already a twist towards the uncanny. The way in which the human being is located in the landscape provides connecting factors for the philosophy of the sublime. In light of the unattainability and size of nature, humans feel small and overwhelmed.

Christopher Orr works most times on several paintings at the same time. An important source of information for his creative process proves to be his images archive, consisting of old magazines - especially National Geographic from the 1930s to the 70s - and books. Orr also draws on the “old masters” of painting like Tiepolo, Vermeer, Bosch, Hals, van Eyck, Caravaggio and others. His passion for details in the works of his role models finds its way into his own paintings. He quotes, as it were, a certain selected point from the entire historical quote. His archive also includes thematic collections of images which are grouped, for example, into the scientific, the mystical or the spherical.

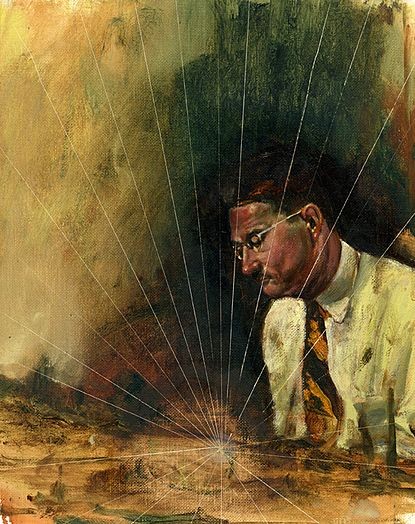

Many of the characters, objects, landscapes and the activities of the characters originate in the archive. The artist assembles them into a collage, drawing from different sources, by first conceiving and drawing them in his sketchbook. The oil paintings resulting from it, mostly in small format and produced with superb dexterity, entice one to look more closely, and it is not only the brush strokes, both coating and removing, that strike but also time and again the breaks in temporalities. In Häxan Apparatus (2012) for instance, a male figure whose clothing style could be both contemporary and from the last twenty years, stands in a landscape that could have sprung from a Renaissance painting. The object the figure wears slung around his neck cannot be identified by the uninitiated. The title, which suggests a cross-reference to the Swedish silent film “Häxan” from 1922 - a film about the history of the witch hunts, associates the object with the occult and witchcraft. Even the rays emanating from a staff of the figure makes one think of it. The fact that a man in jeans, a red shirt and lace-up shoes is presumably executing something occult within an Old Master landscape that we know from art historical masterpieces, renders a very specific singularity to the picture. Detached temporal moments connect, the incompatible can be read together, old and new unites and forms anew, along with us as viewers, a connection with the present.

A recurring feature in Christopher Orr’s paintings is the use of different figure sizes that are presented regardless of issues of perspective and image consistency. In Lighten Our Darkness (2010), for instance, two female figures clad in aprons face each other and raise a hand, as if they have performed a magic ritual. They have identical faces and are mirror images of each other, but one figure inexplicably stands a third taller than the other one. In The Cunning Folk (2012) as well, an over-sized male figure in a suit and a relatively tiny bare-chested male figure are situated in the same visual space. There is no linear narrative which gives us a reason for it.

The described motif inconsistencies, the dramatic composition of the images in light and dark, and the disintegration of temporalities leave room for one’s own individual narrative in the mind. Christopher Orr is, so to speak, the director of the movies in our head.

Sabine Schaschl

Light Shining Darkly

20 April - 30 June 2013

Kunsthaus Baselland is very pleased to present the first institutional solo exhibition of the British artist Christopher Orr (born 1967 in Scotland, lives and works in London). The exhibition presents a series of works from recent years supplemented by new works created specifically for the exhibition.

Orr belongs to the most impressive among contemporary painters. His works have been shown, inter alia, at the 54th Venice Biennale in the Palazzo Zenobio, the CAPC Musée d’Art Contemporain, Bordeaux, the Kunsthalle Brandts in Odense at the Tate Britain, as well as regularly in the galleries of Hauser & Wirth and IBID Projects.

As the title “Light Shining Darkly” already evokes, Orr’s paintings show locations and scenes where something seemingly mystical, supernatural, dark or sinister happens, or you, as the viewer, presage something like this may happen. The landscape scenes in which protagonists act are characterised by special lighting effects. Sometimes a night landscape with an incoming, diffuse cone of light reveals strollers (Descent, 2004), sometimes people stand in front of a rocky slope (Silent One, 2010), or inexplicable scenes take place in a forest in the dead of night (The Silence of Afterwards, 2010 ). Time and again it is the specific use of lighting effects, which at first glance give the motifs already a twist towards the uncanny. The way in which the human being is located in the landscape provides connecting factors for the philosophy of the sublime. In light of the unattainability and size of nature, humans feel small and overwhelmed.

Christopher Orr works most times on several paintings at the same time. An important source of information for his creative process proves to be his images archive, consisting of old magazines - especially National Geographic from the 1930s to the 70s - and books. Orr also draws on the “old masters” of painting like Tiepolo, Vermeer, Bosch, Hals, van Eyck, Caravaggio and others. His passion for details in the works of his role models finds its way into his own paintings. He quotes, as it were, a certain selected point from the entire historical quote. His archive also includes thematic collections of images which are grouped, for example, into the scientific, the mystical or the spherical.

Many of the characters, objects, landscapes and the activities of the characters originate in the archive. The artist assembles them into a collage, drawing from different sources, by first conceiving and drawing them in his sketchbook. The oil paintings resulting from it, mostly in small format and produced with superb dexterity, entice one to look more closely, and it is not only the brush strokes, both coating and removing, that strike but also time and again the breaks in temporalities. In Häxan Apparatus (2012) for instance, a male figure whose clothing style could be both contemporary and from the last twenty years, stands in a landscape that could have sprung from a Renaissance painting. The object the figure wears slung around his neck cannot be identified by the uninitiated. The title, which suggests a cross-reference to the Swedish silent film “Häxan” from 1922 - a film about the history of the witch hunts, associates the object with the occult and witchcraft. Even the rays emanating from a staff of the figure makes one think of it. The fact that a man in jeans, a red shirt and lace-up shoes is presumably executing something occult within an Old Master landscape that we know from art historical masterpieces, renders a very specific singularity to the picture. Detached temporal moments connect, the incompatible can be read together, old and new unites and forms anew, along with us as viewers, a connection with the present.

A recurring feature in Christopher Orr’s paintings is the use of different figure sizes that are presented regardless of issues of perspective and image consistency. In Lighten Our Darkness (2010), for instance, two female figures clad in aprons face each other and raise a hand, as if they have performed a magic ritual. They have identical faces and are mirror images of each other, but one figure inexplicably stands a third taller than the other one. In The Cunning Folk (2012) as well, an over-sized male figure in a suit and a relatively tiny bare-chested male figure are situated in the same visual space. There is no linear narrative which gives us a reason for it.

The described motif inconsistencies, the dramatic composition of the images in light and dark, and the disintegration of temporalities leave room for one’s own individual narrative in the mind. Christopher Orr is, so to speak, the director of the movies in our head.

Sabine Schaschl