The Eternal Flame

10 Aug - 05 Oct 2008

THE ETERNAL FLAME

On the promise of eternity

10 August 2008 – 5 October 2008

A project by Burkhard Meltzer and Sabine Schaschl

“Eternity” is one of those words we use without really having a concept of what they refer to. As an existential experience of our life-time and a metaphysical idea of something “beyond time”, our relationship with time is a philosophical evergreen. The Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle always assumed that matter existed eternally when discussing the big mystery of how the world came into being. They did not believe that the world as known by humankind could simply have materialized out of nothing. On the threshold from antiquity to the Middle Ages, the theologian and philosopher Augustine considered eternity to be an everlasting force and even called it a negation of all time. In subsequent centuries, theologians and philosophers often understood eternity to mean there was hope for the existence of God. Henri Bergson, in the 19th century, and Martin Heidegger, in the 20th, however, had other, more modern difficulties with the notion of eternity. Bergson was particularly concerned with the precarious shortcomings of language to even describe eternity, while Heidegger tried to find eternity in art, for instance – in order to make the unimaginable more graspable. The point where language and the aesthetic experience of art intersect seems to be propitious for reflections on eternity.

At the juncture where space-time orientation seems to dissolve, we can start thinking about eternity. Although the dimensions of eternity are almost impossible to imagine, they can still somehow be experienced by the individual. That paradox is the point of departure for this exhibition, and it is reflected in the work of contemporary artists moving between the idiom of abstraction and landscape motifs – two of the most important pictorial languages of modern art that make reflections on eternity conceivable.

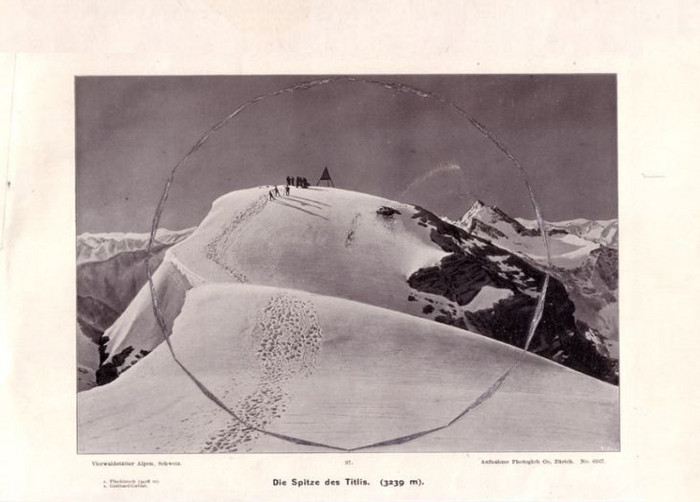

Claudia Wieser, for instance, combines both levels when she adds a geometrical shape in silver leaf to printed photographs of impressive mountain-scapes taken from 20th century travel literature (Kessel der 5 Seen, 2007). One could be tempted to consider the silver shape as a token of how forms continually develop in nature.

What lies between the idea of eternity and the organisation of time in our daily lives? The question of the interstitial spaces in images, language and time sequences is explored by the Belgian artist Kris Martin. A life-size mirror bears the inscription THE END in mirror-inverted curved letters. The mirror shows the room in retrospect together with the viewer. The inscription, with its pathos reminiscent of old movies, adds a temporal layer to the spatial mirror image. Factually, space-time ends at this mirror wall; for the viewer, however, it is right there that an illusionary space begins combining language and the mirror image.

In the film “Starfield”(2004), Jordan Wolfson lets a dot develop into a line that seems to continue eternally. Although this is only a simple version of the old “Starfield” screensaver, you could also see this abstract film as a possible depiction of infinity and eternity. In the perspectival illusion of the film, the lines appear to be parallel ; when viewing the animation as a two-dimensional image, however, the lines converge and might actually meet. This would mean the fulfilment of the mathematical axiom of “parallel lines meeting at infinity”. Quantum physicists also speak about a continuous present that makes do without any fact-creating action. According to the British philosopher Colin McGinn this is merely a “phase of potentiality”.

We are as unable to conceive of eternal duration as of present transience. And yet we at least have a linguistic concept of “eternity” that enables us to use it in statements. Let us try to put it this way: although eternity is not imaginable, it is still possible. And particularly at the boundaries of aesthetic experience – in the work of certain contemporary artists, for instance – this possibility becomes conceivable.

On the promise of eternity

10 August 2008 – 5 October 2008

A project by Burkhard Meltzer and Sabine Schaschl

“Eternity” is one of those words we use without really having a concept of what they refer to. As an existential experience of our life-time and a metaphysical idea of something “beyond time”, our relationship with time is a philosophical evergreen. The Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle always assumed that matter existed eternally when discussing the big mystery of how the world came into being. They did not believe that the world as known by humankind could simply have materialized out of nothing. On the threshold from antiquity to the Middle Ages, the theologian and philosopher Augustine considered eternity to be an everlasting force and even called it a negation of all time. In subsequent centuries, theologians and philosophers often understood eternity to mean there was hope for the existence of God. Henri Bergson, in the 19th century, and Martin Heidegger, in the 20th, however, had other, more modern difficulties with the notion of eternity. Bergson was particularly concerned with the precarious shortcomings of language to even describe eternity, while Heidegger tried to find eternity in art, for instance – in order to make the unimaginable more graspable. The point where language and the aesthetic experience of art intersect seems to be propitious for reflections on eternity.

At the juncture where space-time orientation seems to dissolve, we can start thinking about eternity. Although the dimensions of eternity are almost impossible to imagine, they can still somehow be experienced by the individual. That paradox is the point of departure for this exhibition, and it is reflected in the work of contemporary artists moving between the idiom of abstraction and landscape motifs – two of the most important pictorial languages of modern art that make reflections on eternity conceivable.

Claudia Wieser, for instance, combines both levels when she adds a geometrical shape in silver leaf to printed photographs of impressive mountain-scapes taken from 20th century travel literature (Kessel der 5 Seen, 2007). One could be tempted to consider the silver shape as a token of how forms continually develop in nature.

What lies between the idea of eternity and the organisation of time in our daily lives? The question of the interstitial spaces in images, language and time sequences is explored by the Belgian artist Kris Martin. A life-size mirror bears the inscription THE END in mirror-inverted curved letters. The mirror shows the room in retrospect together with the viewer. The inscription, with its pathos reminiscent of old movies, adds a temporal layer to the spatial mirror image. Factually, space-time ends at this mirror wall; for the viewer, however, it is right there that an illusionary space begins combining language and the mirror image.

In the film “Starfield”(2004), Jordan Wolfson lets a dot develop into a line that seems to continue eternally. Although this is only a simple version of the old “Starfield” screensaver, you could also see this abstract film as a possible depiction of infinity and eternity. In the perspectival illusion of the film, the lines appear to be parallel ; when viewing the animation as a two-dimensional image, however, the lines converge and might actually meet. This would mean the fulfilment of the mathematical axiom of “parallel lines meeting at infinity”. Quantum physicists also speak about a continuous present that makes do without any fact-creating action. According to the British philosopher Colin McGinn this is merely a “phase of potentiality”.

We are as unable to conceive of eternal duration as of present transience. And yet we at least have a linguistic concept of “eternity” that enables us to use it in statements. Let us try to put it this way: although eternity is not imaginable, it is still possible. And particularly at the boundaries of aesthetic experience – in the work of certain contemporary artists, for instance – this possibility becomes conceivable.