Closer to Nature

Building with Fungi, Trees, Mud

16 Feb - 14 Oct 2024

Exhibition view “Closer to Nature. Building with Fungi, Trees, Mud”, Berlinische Galerie © Photo: Harry Schnitger

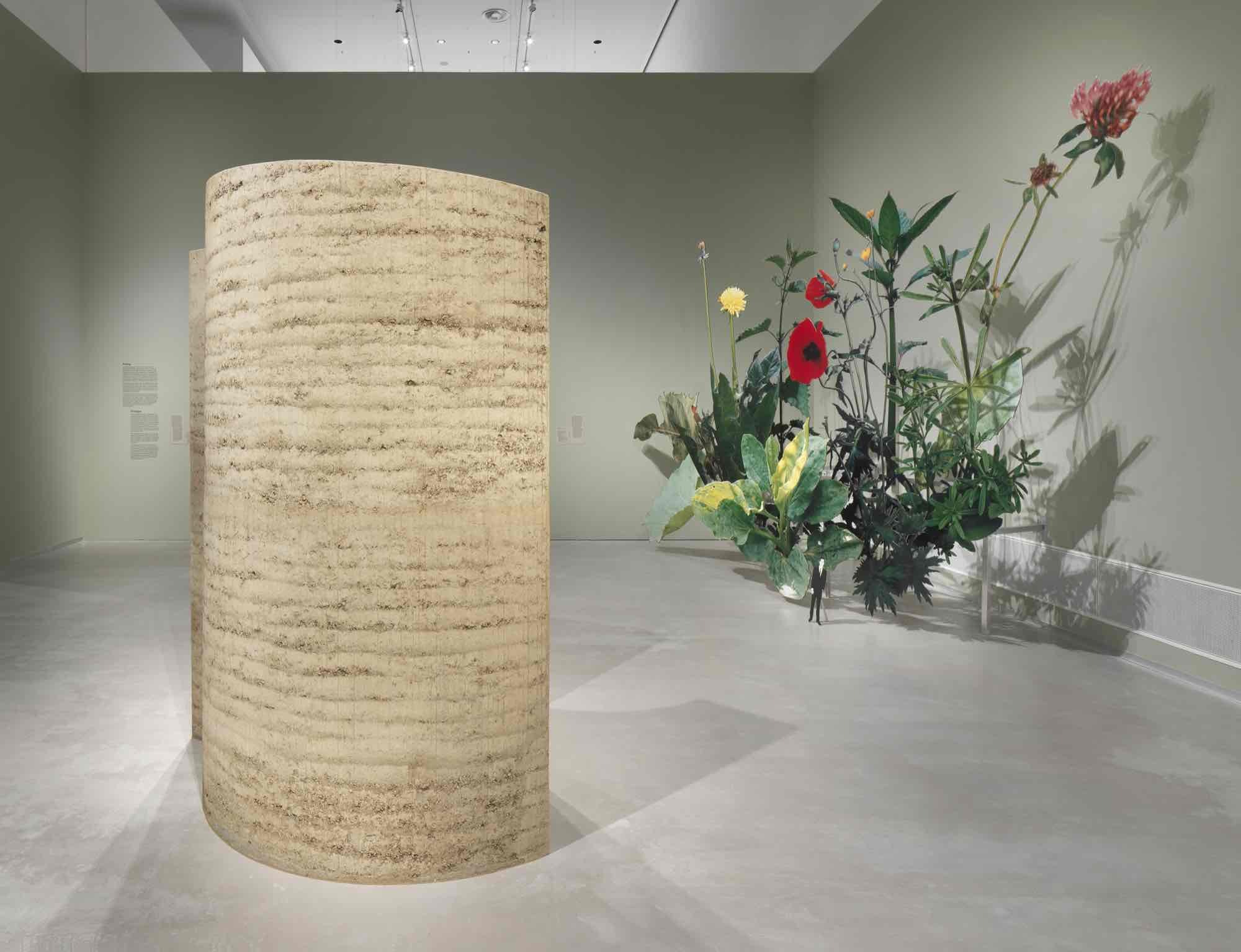

Exhibition view “Closer to Nature. Building with Fungi, Trees, Mud” (work shown: Thomas Eller, THE Self with a Large Piece of Lawn, 1992), Berlinische Galerie © Photo: Harry Schnitger

Exhibition view “Closer to Nature. Building with Fungi, Trees, Mud”, Berlinische Galerie © Photo: Harry Schnitger

Exhibition view “Closer to Nature. Building with Fungi, Trees, Mud”, Berlinische Galerie © Photo: Harry Schnitger

Exhibition view “Closer to Nature. Building with Fungi, Trees, Mud”, Berlinische Galerie © Photo: Harry Schnitger

Exhibition view “Closer to Nature. Building with Fungi, Trees, Mud”, Berlinische Galerie © Photo: Harry Schnitger

Exhibition view “Closer to Nature. Building with Fungi, Trees, Mud”, Berlinische Galerie © Photo: Harry Schnitger

Exhibition view “Closer to Nature. Building with Fungi, Trees, Mud”, Berlinische Galerie © Photo: Harry Schnitger

Exhibition view “Closer to Nature. Building with Fungi, Trees, Mud”, Berlinische Galerie © Photo: Harry Schnitger

Exhibition view “Closer to Nature. Building with Fungi, Trees, Mud”, Berlinische Galerie © Photo: Harry Schnitger

Architecture and nature inevitably compete for space. That poses a dilemma when resources are finite and the demand for space keeps growing. Besides, we know that the construction sector generates huge waste and emissions. All this has raised issues about the role of architecture: Does it need a shift in perspective? Could we be building with nature instead of against it? This exhibition showcases three Berlin-based projects: the experimental building MY-CO SPACE (2021, MY-CO-X), a competition entry for the Futurium exhibition venue (2012, 3rd prize, ludwig.schoenle, now OLA – Office for Living Architecture), and the Chapel of Reconciliation built on Bernauer Strasse (1996–2000, Reitermann/Sassenroth Architekten with Lehm Ton Erde Baukunst – Martin Rauch).

New sensuality

These buildings draw on the potential of fungi, trees and mud. Doing so lends them not just an ecological quality but an entirely new character: they breathe, grow and take on life. As a result, the architecture acquires a surprising sensuality. When our senses respond to the space, we experience our contact with the environment physically: the sustainable impact is not merely material. Installations, some purpose-designed for this show, will enable visitors to discover the materiality and aesthetic value of building with these natural materials. The genesis of these three projects and the strategies behind them are illustrated by about 45 original plans and sketches, photographs, renderings, objects and models.

Sustainable building strategies

The teams presented here – the SciArt collective MY-CO-X from Berlin, the Office for Living Architecture (OLA) from Stuttgart and the group collaborating with Martin Rauch, the clay virtuoso from Vorarlberg – all boast an international reputation or rank as pioneers in the fields of fungal research, botanical architecture and modern-day mud construction. They all share a desire to combine different disciplines and to merge cutting-edge technology with traditional practice.

In pursuit of building methods that place less pressure on the climate, they have established new links between architecture and the world outside. Fungi, trees and mud are not just building materials but partners, partly because the architects are learning from them and partly because they influence the structure both conceptually and formally. Collaboration and combination are closing the gap between architecture and nature.

The building transition

There is much talk at present about a transition in the construction sector. The buildings and designs on show here are prominent examples. They symbolise a belief that sustainable architecture cannot be achieved simply by technical means, such as by focusing on ecological materials and energy efficiency. They go further by adding a deeper cultural dimension to the sustainability debate, questioning the conventional relationship between architecture and nature and promoting an awareness for things in our environment not made by human hand.

Nature v. architecture

The conflict between nature and architecture is ancient and fundamental. The basic function of a building was to protect us from natural forces such as weather and wild animals. Of all cultural techniques, architecture has served most clearly to keep nature at bay, suppress it or at best exploit it. Even in 1925, Le Corbusier, a hero of modernism, described the construction of cities as “a human operation directed against nature”. The history of architecture records many critical responses and counter-proposals, sometimes utopian or visionary, sometimes pragmatic and successful. In Berlin, an ecological architecture movement emerged around the International Building Exhibition (IBA) in 1987. That, too, promoted natural materials and sought to integrate buildings more effectively into environmental cycles, drawing on solar energy and rainwater, respecting the vegetation available and incorporating it into the built fabric. When Berlin was redeveloped as the capital of a newly unified Germany, accompanied by politically endorsed discourse about “Critical Reconstruction”, the focus shifted again, and those ideas largely dried up. Much of the resulting architecture sought to echo history and the opposition between nature and architecture remained unchallenged, still driving the competition for space and resources. But now the time seems right to reassess the future of that relationship.

The exhibition begins with photographic art (from the museum collection or loaned) by Elisabeth Niggemeyer, Ulrich Wüst and Thomas Eller. The photographs by Niggemeyer and Wüst illustrate an apparent incompatibility and stand-off between post-war modernist architecture and forms that take shape organically. Thomas Eller’s photo-installation addresses a new perspective by quoting Albrecht Dürer’s well-known watercolour “The Large Piece of Turf” of 1503. In his piece, the humans look very small and nature oversized.

New sensuality

These buildings draw on the potential of fungi, trees and mud. Doing so lends them not just an ecological quality but an entirely new character: they breathe, grow and take on life. As a result, the architecture acquires a surprising sensuality. When our senses respond to the space, we experience our contact with the environment physically: the sustainable impact is not merely material. Installations, some purpose-designed for this show, will enable visitors to discover the materiality and aesthetic value of building with these natural materials. The genesis of these three projects and the strategies behind them are illustrated by about 45 original plans and sketches, photographs, renderings, objects and models.

Sustainable building strategies

The teams presented here – the SciArt collective MY-CO-X from Berlin, the Office for Living Architecture (OLA) from Stuttgart and the group collaborating with Martin Rauch, the clay virtuoso from Vorarlberg – all boast an international reputation or rank as pioneers in the fields of fungal research, botanical architecture and modern-day mud construction. They all share a desire to combine different disciplines and to merge cutting-edge technology with traditional practice.

In pursuit of building methods that place less pressure on the climate, they have established new links between architecture and the world outside. Fungi, trees and mud are not just building materials but partners, partly because the architects are learning from them and partly because they influence the structure both conceptually and formally. Collaboration and combination are closing the gap between architecture and nature.

The building transition

There is much talk at present about a transition in the construction sector. The buildings and designs on show here are prominent examples. They symbolise a belief that sustainable architecture cannot be achieved simply by technical means, such as by focusing on ecological materials and energy efficiency. They go further by adding a deeper cultural dimension to the sustainability debate, questioning the conventional relationship between architecture and nature and promoting an awareness for things in our environment not made by human hand.

Nature v. architecture

The conflict between nature and architecture is ancient and fundamental. The basic function of a building was to protect us from natural forces such as weather and wild animals. Of all cultural techniques, architecture has served most clearly to keep nature at bay, suppress it or at best exploit it. Even in 1925, Le Corbusier, a hero of modernism, described the construction of cities as “a human operation directed against nature”. The history of architecture records many critical responses and counter-proposals, sometimes utopian or visionary, sometimes pragmatic and successful. In Berlin, an ecological architecture movement emerged around the International Building Exhibition (IBA) in 1987. That, too, promoted natural materials and sought to integrate buildings more effectively into environmental cycles, drawing on solar energy and rainwater, respecting the vegetation available and incorporating it into the built fabric. When Berlin was redeveloped as the capital of a newly unified Germany, accompanied by politically endorsed discourse about “Critical Reconstruction”, the focus shifted again, and those ideas largely dried up. Much of the resulting architecture sought to echo history and the opposition between nature and architecture remained unchallenged, still driving the competition for space and resources. But now the time seems right to reassess the future of that relationship.

The exhibition begins with photographic art (from the museum collection or loaned) by Elisabeth Niggemeyer, Ulrich Wüst and Thomas Eller. The photographs by Niggemeyer and Wüst illustrate an apparent incompatibility and stand-off between post-war modernist architecture and forms that take shape organically. Thomas Eller’s photo-installation addresses a new perspective by quoting Albrecht Dürer’s well-known watercolour “The Large Piece of Turf” of 1503. In his piece, the humans look very small and nature oversized.