COMMA 30: David Jablonowski

13 Jan - 13 Feb 2011

COMMA 30:

DAVID JABLONOWSKI

13 January - 13 February 2011

1.33:1, Hard Copy, Display Sequences, Multi Channel Projection

The Azadi Tower (known before the revolution as the Shahyãd Ãryãmehr Tower) was donated by the Mayor of Tehran to the Shah in 1971 and dedicated to the memory of the Kings of Persia. Combining both modernist and Islamic architectural styles, this marble clad structure rises on four fluted legs from an ornately patterned square of lawns, fountains and walkways ringed round with traffic, to be one of the idiosyncratic landmarks of world architecture. In the basement there is a museum celebrating 2,500 years of Persian history. Along with unique artefacts such as early examples of writing on stone tablets, Miniature Painting, and illuminated copies of the Koran, there is a sound and light theatre designed by a Czech company which was added to the exhibition in 1975. This gives an account of the nation's history and pre-history in a spectacular and immersive display, using extensive still and moving images projected at different heights and onto a variety of surfaces, hanging globes, lighting effects, and water features. The experience of the viewer is disembodied, as the images and objects merge as illuminated islands in a darkened space. This paradoxically, might have the opposite effect than the one intended by the designers who wished to emphasise the continuity between ancient empire, Islamic golden age and the Shah's regime. Instead they produced a space where history is staged as something fantastical and discontinuous. Film footage of this sound and light theatre appears in the new installation 1.33:1, Hard Copy, Display Sequences, Multi Channel Projection by the artist David Jablonowski which is currently being exhibited at Bloomberg SPACE. Shot by the artist during a visit to Iran in 2009, this footage provides an interesting counterpoint to the installation itself, and points the viewer towards a number of related considerations, including the mechanics of exhibition display systems and the technologies through which information is mediated.

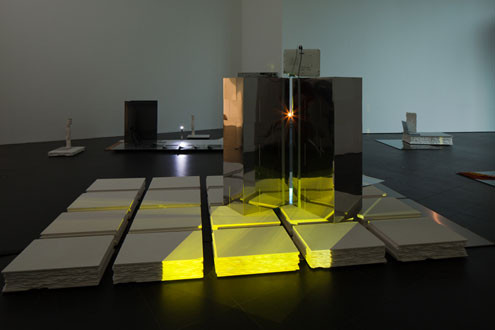

Individually, Jablonowski's sculptures have autonomy as artworks, and when assembled they produce an environment. Each one is carefully layered from different elements with the artist playing off reflective and non reflective surfaces, organic and synthetic materials, the crafted and the manufactured, as well as solid and virtual components, shadows and light. The installation includes a series of basins of 4:3 aspect ratio, filled with water which capture light and moving images, white plaster blocks waffled and textured like sheets of handmade paper, mirrored cubes used as pedestals and reflective surfaces, rectangular steel plates of different sizes, and four projectors aimed variously towards the wall as well as down onto the surface of the sculptures themselves. All four projectors play the same sequence in a loop which includes footage of an automated display case from the Egyptian gallery of the Neues Museum in Berlin, images of the artist's previous works with elements of animation, and the above mentioned sound and light theatre from the Azadi Tower in Tehran. All of these elements come together in a series of informal geometric clusters arranged in diagonal lines across the room. In order to arrive at this layout, and mainly for his own reference, during the installation the artist used a template taken from Arabic calligraphy, where the lines of text move diagonally across the page, adding another layer to the composition of the work, even if this is not apparent to the viewer. Elsewhere in the exhibition in a second set of sculptures - All Share, Think Free Office (Desktop) (2010), Multiple, 1.33:1 (2010) and Multiple, Gestetner, 1.78:1 (2010) - the artist introduces components relating to different generations of reproductive technology including offset plates used in printing processes and modern day flat bed scanners. Looking back you can see how he has utilised several of these elements in previous works, developing his own vocabulary of objects, images and materials that get to be recycled and configured differently in different contexts.

Jablonowski's interest in display systems and information transfer has as much to do with the hardware that is

used in the staging of knowledge as it has with the knowledge itself. This relates the installation to exhibition design in general, as even the most sober museum displays involve a high degree of artifice and include a consideration of interior design, exhibition furniture, lighting and props, colour schemes, text and graphics, despite their supposed neutrality. A particular tradition in exhibition making actively embraces this artificiality, seeking to engage the viewer with theatrical effects and implicate them through interactive displays. This approach was introduced with a flourish born of revolutionary enthusiasm by the artist El Lissitzky and his team of thirty collaborators when in 1928 they participated in 'Der Internationalen Presse-Ausstellung (the International Press Exhibition) in Cologne. Lissitzky designed a pavilion whose theme was the role of the media in Soviet society, using a number of ground breaking techniques which captivated audiences and virtually gave rise to exhibition design as art form and medium in its own right. Divided into twenty different sections, the Soviet pavilion provided an all round aesthetic experience through colour, form, movement and light and included film, large scale photomontage, special effects and mechanical elements such as spinning globes, as well as introducing a range of new materials such as cellophane and Plexiglas. What is notable about Lissitzky's pavilion is how it aimed to communicate a revolutionary concept of the media and simultaneously embodied this notion by employing sophisticated media techniques.

Similar to the Czech designers of the sound and light theatre housed in the basement of the Azadi tower, Lissitzky was intent on transmitting his message as well as being intensely interested in exploring novel ways to do this. Both displays create an excessive theatricality that we admire in one and perhaps ridicule in the other. In Jablonowski's installation 1.33:1, Hard Copy, Display Sequences, Multi Channel Projection the attention is exclusively on the mechanical aspect of information transmission as there is no message or even subject matter that can be attributed to the work. While it contains data, in the form of moving images that are transmitted as projections, these are duplicated, looped, fragmented and reflected to the point where their narrative or documentary value is lost. If Jablonowski's work seems to be in part about the distortion of information, it is more substantially concerned with the material nuts and bolts that are needed in order build an information system. It is as if you walked into the British Museum and decided to concern yourself in particular with the vitrine in front of you, its metal casing, wooden panels and interior lighting rather than the ancient artefact inside. Or more precisely as if you viewed all of these things as one integrated assemblage. However Jablonowski's work is not deconstructive in the sense that it might seek to unmask the structures which organise knowledge in accordance to hierarchies of power and vested interest. Instead the artist seems to revel in the idiom of exhibition display systems and reproduction processes themselves, as a formal language and a game of aesthetic choices. In 1.33:1, Hard Copy, Display Sequences, Multi Channel Projection, the audience is invited to approach these choices as the main emphasis of the work, with the artist's layering of materials and engineering of movement through reflection, shadow and light, making this experience both detailed and immersive. Jablonowski has said of his sculptures that they have more to do with cinema than with the minimalist works which they sometimes resemble, and here one is tempted to make a link to the Materialist Film genre of artists such as Peter Gidal and Michael Snow. In a parallel with Jablonowski's practice, Structural/Materialist Film places the utmost importance on the fact of the film itself, and so a consideration of the camera, the frame, the lighting, the projection and the passing of time become the subject of the work.

Grant Watson

Grant Watson is a curator and writer based in London.

DAVID JABLONOWSKI

13 January - 13 February 2011

1.33:1, Hard Copy, Display Sequences, Multi Channel Projection

The Azadi Tower (known before the revolution as the Shahyãd Ãryãmehr Tower) was donated by the Mayor of Tehran to the Shah in 1971 and dedicated to the memory of the Kings of Persia. Combining both modernist and Islamic architectural styles, this marble clad structure rises on four fluted legs from an ornately patterned square of lawns, fountains and walkways ringed round with traffic, to be one of the idiosyncratic landmarks of world architecture. In the basement there is a museum celebrating 2,500 years of Persian history. Along with unique artefacts such as early examples of writing on stone tablets, Miniature Painting, and illuminated copies of the Koran, there is a sound and light theatre designed by a Czech company which was added to the exhibition in 1975. This gives an account of the nation's history and pre-history in a spectacular and immersive display, using extensive still and moving images projected at different heights and onto a variety of surfaces, hanging globes, lighting effects, and water features. The experience of the viewer is disembodied, as the images and objects merge as illuminated islands in a darkened space. This paradoxically, might have the opposite effect than the one intended by the designers who wished to emphasise the continuity between ancient empire, Islamic golden age and the Shah's regime. Instead they produced a space where history is staged as something fantastical and discontinuous. Film footage of this sound and light theatre appears in the new installation 1.33:1, Hard Copy, Display Sequences, Multi Channel Projection by the artist David Jablonowski which is currently being exhibited at Bloomberg SPACE. Shot by the artist during a visit to Iran in 2009, this footage provides an interesting counterpoint to the installation itself, and points the viewer towards a number of related considerations, including the mechanics of exhibition display systems and the technologies through which information is mediated.

Individually, Jablonowski's sculptures have autonomy as artworks, and when assembled they produce an environment. Each one is carefully layered from different elements with the artist playing off reflective and non reflective surfaces, organic and synthetic materials, the crafted and the manufactured, as well as solid and virtual components, shadows and light. The installation includes a series of basins of 4:3 aspect ratio, filled with water which capture light and moving images, white plaster blocks waffled and textured like sheets of handmade paper, mirrored cubes used as pedestals and reflective surfaces, rectangular steel plates of different sizes, and four projectors aimed variously towards the wall as well as down onto the surface of the sculptures themselves. All four projectors play the same sequence in a loop which includes footage of an automated display case from the Egyptian gallery of the Neues Museum in Berlin, images of the artist's previous works with elements of animation, and the above mentioned sound and light theatre from the Azadi Tower in Tehran. All of these elements come together in a series of informal geometric clusters arranged in diagonal lines across the room. In order to arrive at this layout, and mainly for his own reference, during the installation the artist used a template taken from Arabic calligraphy, where the lines of text move diagonally across the page, adding another layer to the composition of the work, even if this is not apparent to the viewer. Elsewhere in the exhibition in a second set of sculptures - All Share, Think Free Office (Desktop) (2010), Multiple, 1.33:1 (2010) and Multiple, Gestetner, 1.78:1 (2010) - the artist introduces components relating to different generations of reproductive technology including offset plates used in printing processes and modern day flat bed scanners. Looking back you can see how he has utilised several of these elements in previous works, developing his own vocabulary of objects, images and materials that get to be recycled and configured differently in different contexts.

Jablonowski's interest in display systems and information transfer has as much to do with the hardware that is

used in the staging of knowledge as it has with the knowledge itself. This relates the installation to exhibition design in general, as even the most sober museum displays involve a high degree of artifice and include a consideration of interior design, exhibition furniture, lighting and props, colour schemes, text and graphics, despite their supposed neutrality. A particular tradition in exhibition making actively embraces this artificiality, seeking to engage the viewer with theatrical effects and implicate them through interactive displays. This approach was introduced with a flourish born of revolutionary enthusiasm by the artist El Lissitzky and his team of thirty collaborators when in 1928 they participated in 'Der Internationalen Presse-Ausstellung (the International Press Exhibition) in Cologne. Lissitzky designed a pavilion whose theme was the role of the media in Soviet society, using a number of ground breaking techniques which captivated audiences and virtually gave rise to exhibition design as art form and medium in its own right. Divided into twenty different sections, the Soviet pavilion provided an all round aesthetic experience through colour, form, movement and light and included film, large scale photomontage, special effects and mechanical elements such as spinning globes, as well as introducing a range of new materials such as cellophane and Plexiglas. What is notable about Lissitzky's pavilion is how it aimed to communicate a revolutionary concept of the media and simultaneously embodied this notion by employing sophisticated media techniques.

Similar to the Czech designers of the sound and light theatre housed in the basement of the Azadi tower, Lissitzky was intent on transmitting his message as well as being intensely interested in exploring novel ways to do this. Both displays create an excessive theatricality that we admire in one and perhaps ridicule in the other. In Jablonowski's installation 1.33:1, Hard Copy, Display Sequences, Multi Channel Projection the attention is exclusively on the mechanical aspect of information transmission as there is no message or even subject matter that can be attributed to the work. While it contains data, in the form of moving images that are transmitted as projections, these are duplicated, looped, fragmented and reflected to the point where their narrative or documentary value is lost. If Jablonowski's work seems to be in part about the distortion of information, it is more substantially concerned with the material nuts and bolts that are needed in order build an information system. It is as if you walked into the British Museum and decided to concern yourself in particular with the vitrine in front of you, its metal casing, wooden panels and interior lighting rather than the ancient artefact inside. Or more precisely as if you viewed all of these things as one integrated assemblage. However Jablonowski's work is not deconstructive in the sense that it might seek to unmask the structures which organise knowledge in accordance to hierarchies of power and vested interest. Instead the artist seems to revel in the idiom of exhibition display systems and reproduction processes themselves, as a formal language and a game of aesthetic choices. In 1.33:1, Hard Copy, Display Sequences, Multi Channel Projection, the audience is invited to approach these choices as the main emphasis of the work, with the artist's layering of materials and engineering of movement through reflection, shadow and light, making this experience both detailed and immersive. Jablonowski has said of his sculptures that they have more to do with cinema than with the minimalist works which they sometimes resemble, and here one is tempted to make a link to the Materialist Film genre of artists such as Peter Gidal and Michael Snow. In a parallel with Jablonowski's practice, Structural/Materialist Film places the utmost importance on the fact of the film itself, and so a consideration of the camera, the frame, the lighting, the projection and the passing of time become the subject of the work.

Grant Watson

Grant Watson is a curator and writer based in London.