Lee Ufan

16 Jan - 20 Feb 2010

LEE UFAN

January 16 - February 20, 2010

Opening Reception: Saturday, January 16th, 6-8pm

The Breath of a Margin

The artworks I create are all tapestries of intimate breathing between me and the world. Therefore, seeing is not the confirmation of an object but a quiet concert of breathing between the work, the world, and the viewer.

—Lee Ufan

Blum & Poe is pleased to present the first West-coast U.S. gallery exhibition of internationally acclaimed artist Lee Ufan. Achieving critical praise at the 52nd Venice Biennale for his exhibition, Resonance at the Palazzo Palumbo Fossati in 2007, Lee has held major retrospectives at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (2009), Yokohama Museum of Art (2005), Musée d’Art Moderne de Saint-Étienne Métropole (2005), Kunstmuseum Bonn (2001), and Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris (1997). Lee has received many prestigious awards including the Praemium Imperiale prize in painting in 2001 and UNESCO Prize in 2000. He has served as a visiting professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and professor of art at Tama Art University in Tokyo from 1973 to 2007. A collection of Lee’s writings was recently published in The Art of Encounter (Lisson Gallery, 2008).

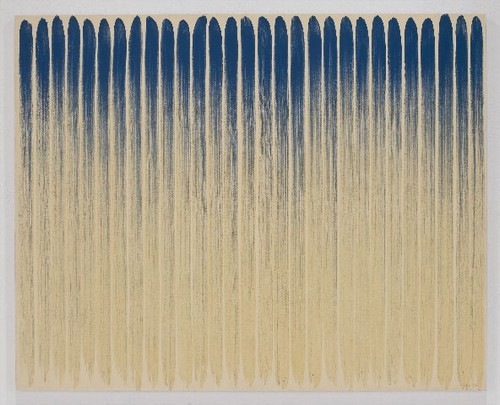

The show will present a historical survey of paintings and works on paper from 1974 to the present that include the artist’s key series, From Line, From Point and With Winds, which demonstrate the development of a breath-like repetition of a gestural act over time. The exhibit will also showcase Dialogue (2007–present), a series of recent large-scale oil on canvas paintings together with three sculptural installations (including one displayed outdoors) from his Relatum (2008) series that combine natural stones with industrially-produced steel plates to explore perception as a symptom of both the materiality and immateriality of space.

Lee Ufan’s career encompasses a spectrum of activity ranging from artist, philosopher, and poet. Born in Korea in 1936 and emigrating to Japan in 1956, Lee obtained a degree in philosophy at Nihon University in 1961 and became widely known as the key ideologue of the critical late-1960s Japanese artistic phenomenon, Mono-ha (School of Things). In dialogue with post-minimalist practices, Lee’s work developed out of Mono-ha’s tenet to explore the phenomenal encounter between natural and industrial objects such as glass, rocks, steel plates, wood, cotton, light bulbs, and Japanese paper in and of themselves arranged directly on the floor or in an outdoor field. What has distinguished Lee is his refined technique of repetition as a studied production of difference developed over time in both his painting and sculptural practice.

A key device that guides Lee’s working method is the notion of lived time (the perpetual passage of the present) through the flux between the visible (actual) and invisible (virtual) both in the production and the reception of his work. This process begins with the rhythm involved in the preparation of each work: the strict choice of materials, the consciousness of each breath and bodily stance, and the strict positioning and application of each material element. Lee’s Relatum series come out of a rigorous search for the precise stone to juxtapose industrially-produced, weathered steel plates, which are at times scattered around the floor to form a capacious field, leaned toward each another like an embrace, or propped against a wall with the steel acting as a screen-like shadow bringing forth the stone’s bodily profile. This sense of movement is also carried in his paintings, which begin by mixing mineral powdered pigments (cobalt blue, orange, and more recently blue-grey) with glue and choosing an appropriate brush to apply onto a large white canvas. Through the continuous repetition of a gestural act in From Line, From Point, and With Winds, Lee loads his brush with mixed pigment and begins applying a single linear stroke or point onto the canvas one by one until the pigment has faded and repeats this process in an orderly fashion. The empty space deliberately left on the white canvas or wall seen especially in his most recent Dialogue series, as well as the light, air and shadows that fall in and around his objects in Relatum are integral to the work’s breath-like contraction and expansion of matter, embodied for example in the thousands of years of erosion the stone has endured and passes forth to our present moment.

Lee has thus followed what one might call an ethics of duration: activating a passage for the viewer to perceive what lies before and around us, even the objects and spaces that are invisible to the eye, as co-existing entities that are brought together to form an affective relationship. Lee has named his practice the art of margins, or yohaku, the resonance between the visible and not visible, the made and unmade, that permeates and reverberates one’s surroundings like a resounding echo or tidal flow. In the artist’s words,

Yohaku (margins) is not empty space but an open site of power in which acts and things and space interact vividly. It is a contradictory world rich in changes and suggestions where a struggle occurs between things that are made and things that are not made. Therefore, yohaku transcends objects and words, leading people to silence, and causing them to breathe infinity.

One can trace this idea of yohaku back to 1969, when Lee staged an ephemeral work consisting of three large sheets of Japanese paper fluttering in the wind, entitled Things and Language outside of the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and later placed directly on the gallery floor as part of the “Ninth Contemporary Art Exhibition of Japan.” The ephemerality of this event (a happening) brings to light both the modernist critique of the permanence of the work of art as well as the object as a symptom of the physicality of its surrounding environment, issues also fundamental to post-minimalist practices in the West. In direct response to the eschewal of traditional conceptions of sculpture in particular, Lee envisions the radical destruction of the art object as an objectified medium for signification and expression, and rather focuses on seeking an open, relational structure that activates the limits of our senses and perception. For example, in Phenomenon and Perception B (1968) presented later that year at the “Trends in Contemporary Art” at the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, a natural stone was placed on a plate of “broken” glass to create the illusion that the stone had been dropped onto the plate, capturing the discord between chance and intention (a nod to and reversal of Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass). Later renamed Relatum (the title given to all of his sculptures up until the present), Lee began exploring the phenomenal encounter between organic and industrial materials and its surrounding environment. As he states, “A work of art, rather than being a self-complete, independent entity, is a resonant relationship with the outside. It exists together with the world, simultaneously what it is and what is not, that is, a relatum.” Here we see how yohaku has its direct roots in the Relatum experiments by re-conceiving the breakdown of the object as a durational form of co-existence between the actuality and potentiality of elements (i.e. ephemerality, chance vs. intention, and relational structure). This idea of duration as a form of ethics is developed not only through his artistic practice, but also in his writings. It was during this time when Lee began publishing his ideas in a series of now seminal articles, which were subsequently compiled into a book entitled, Deai o motomete (The Search for Encounter) (1971).

Lee’s works thus operate as a process of perceiving a perpetually passing present and opens the materiality of the work beyond what is simply seen. Like a shadow, the works make visible the passage of time it profiles. And through this synthesis, each work presents a temporal structure that mediates a phenomenological encounter among viewer, object, and site. This cycle of duration can thus be seen as a mode of eternal recurrence that bind the seemingly opposing elements of destruction and continuity, detachment and relationality, finitude and infinite expanse present in Lee’s oeuvre as a solemn affirmation of life.

–Mika Yoshitake

January 16 - February 20, 2010

Opening Reception: Saturday, January 16th, 6-8pm

The Breath of a Margin

The artworks I create are all tapestries of intimate breathing between me and the world. Therefore, seeing is not the confirmation of an object but a quiet concert of breathing between the work, the world, and the viewer.

—Lee Ufan

Blum & Poe is pleased to present the first West-coast U.S. gallery exhibition of internationally acclaimed artist Lee Ufan. Achieving critical praise at the 52nd Venice Biennale for his exhibition, Resonance at the Palazzo Palumbo Fossati in 2007, Lee has held major retrospectives at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (2009), Yokohama Museum of Art (2005), Musée d’Art Moderne de Saint-Étienne Métropole (2005), Kunstmuseum Bonn (2001), and Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris (1997). Lee has received many prestigious awards including the Praemium Imperiale prize in painting in 2001 and UNESCO Prize in 2000. He has served as a visiting professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and professor of art at Tama Art University in Tokyo from 1973 to 2007. A collection of Lee’s writings was recently published in The Art of Encounter (Lisson Gallery, 2008).

The show will present a historical survey of paintings and works on paper from 1974 to the present that include the artist’s key series, From Line, From Point and With Winds, which demonstrate the development of a breath-like repetition of a gestural act over time. The exhibit will also showcase Dialogue (2007–present), a series of recent large-scale oil on canvas paintings together with three sculptural installations (including one displayed outdoors) from his Relatum (2008) series that combine natural stones with industrially-produced steel plates to explore perception as a symptom of both the materiality and immateriality of space.

Lee Ufan’s career encompasses a spectrum of activity ranging from artist, philosopher, and poet. Born in Korea in 1936 and emigrating to Japan in 1956, Lee obtained a degree in philosophy at Nihon University in 1961 and became widely known as the key ideologue of the critical late-1960s Japanese artistic phenomenon, Mono-ha (School of Things). In dialogue with post-minimalist practices, Lee’s work developed out of Mono-ha’s tenet to explore the phenomenal encounter between natural and industrial objects such as glass, rocks, steel plates, wood, cotton, light bulbs, and Japanese paper in and of themselves arranged directly on the floor or in an outdoor field. What has distinguished Lee is his refined technique of repetition as a studied production of difference developed over time in both his painting and sculptural practice.

A key device that guides Lee’s working method is the notion of lived time (the perpetual passage of the present) through the flux between the visible (actual) and invisible (virtual) both in the production and the reception of his work. This process begins with the rhythm involved in the preparation of each work: the strict choice of materials, the consciousness of each breath and bodily stance, and the strict positioning and application of each material element. Lee’s Relatum series come out of a rigorous search for the precise stone to juxtapose industrially-produced, weathered steel plates, which are at times scattered around the floor to form a capacious field, leaned toward each another like an embrace, or propped against a wall with the steel acting as a screen-like shadow bringing forth the stone’s bodily profile. This sense of movement is also carried in his paintings, which begin by mixing mineral powdered pigments (cobalt blue, orange, and more recently blue-grey) with glue and choosing an appropriate brush to apply onto a large white canvas. Through the continuous repetition of a gestural act in From Line, From Point, and With Winds, Lee loads his brush with mixed pigment and begins applying a single linear stroke or point onto the canvas one by one until the pigment has faded and repeats this process in an orderly fashion. The empty space deliberately left on the white canvas or wall seen especially in his most recent Dialogue series, as well as the light, air and shadows that fall in and around his objects in Relatum are integral to the work’s breath-like contraction and expansion of matter, embodied for example in the thousands of years of erosion the stone has endured and passes forth to our present moment.

Lee has thus followed what one might call an ethics of duration: activating a passage for the viewer to perceive what lies before and around us, even the objects and spaces that are invisible to the eye, as co-existing entities that are brought together to form an affective relationship. Lee has named his practice the art of margins, or yohaku, the resonance between the visible and not visible, the made and unmade, that permeates and reverberates one’s surroundings like a resounding echo or tidal flow. In the artist’s words,

Yohaku (margins) is not empty space but an open site of power in which acts and things and space interact vividly. It is a contradictory world rich in changes and suggestions where a struggle occurs between things that are made and things that are not made. Therefore, yohaku transcends objects and words, leading people to silence, and causing them to breathe infinity.

One can trace this idea of yohaku back to 1969, when Lee staged an ephemeral work consisting of three large sheets of Japanese paper fluttering in the wind, entitled Things and Language outside of the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and later placed directly on the gallery floor as part of the “Ninth Contemporary Art Exhibition of Japan.” The ephemerality of this event (a happening) brings to light both the modernist critique of the permanence of the work of art as well as the object as a symptom of the physicality of its surrounding environment, issues also fundamental to post-minimalist practices in the West. In direct response to the eschewal of traditional conceptions of sculpture in particular, Lee envisions the radical destruction of the art object as an objectified medium for signification and expression, and rather focuses on seeking an open, relational structure that activates the limits of our senses and perception. For example, in Phenomenon and Perception B (1968) presented later that year at the “Trends in Contemporary Art” at the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, a natural stone was placed on a plate of “broken” glass to create the illusion that the stone had been dropped onto the plate, capturing the discord between chance and intention (a nod to and reversal of Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass). Later renamed Relatum (the title given to all of his sculptures up until the present), Lee began exploring the phenomenal encounter between organic and industrial materials and its surrounding environment. As he states, “A work of art, rather than being a self-complete, independent entity, is a resonant relationship with the outside. It exists together with the world, simultaneously what it is and what is not, that is, a relatum.” Here we see how yohaku has its direct roots in the Relatum experiments by re-conceiving the breakdown of the object as a durational form of co-existence between the actuality and potentiality of elements (i.e. ephemerality, chance vs. intention, and relational structure). This idea of duration as a form of ethics is developed not only through his artistic practice, but also in his writings. It was during this time when Lee began publishing his ideas in a series of now seminal articles, which were subsequently compiled into a book entitled, Deai o motomete (The Search for Encounter) (1971).

Lee’s works thus operate as a process of perceiving a perpetually passing present and opens the materiality of the work beyond what is simply seen. Like a shadow, the works make visible the passage of time it profiles. And through this synthesis, each work presents a temporal structure that mediates a phenomenological encounter among viewer, object, and site. This cycle of duration can thus be seen as a mode of eternal recurrence that bind the seemingly opposing elements of destruction and continuity, detachment and relationality, finitude and infinite expanse present in Lee’s oeuvre as a solemn affirmation of life.

–Mika Yoshitake