Per Kirkeby

23 Aug - 28 Sep 2013

PER KIRKEBY

White Masonites

23 August - 28 September 2013

Per Kirkeby - works on masonite in the sixth decade

122 cm x 122 cm

Since 1965, Per Kirkeby has been producing works on hardboard – specifically on masonite - always employing the same format: 122 x 122 cm. Prior to starting to paint, Kirkeby was closely associated with the Experimental Art School in Copenhagen in 1962, at a moment when painting seemed to have lost its validity, where he was involved in video projects, happenings and Fluxus events.

Against this backdrop, it is understandable, as he himself wrote, that he felt like a traitor when, in spite of this, he painted.1 "Kirkeby continuously struggles with a feeling of not being of his time, of wishing to hold on to outmoded, outdated material".2 In this situation, masonite panels, industrially produced, far from artistic, and acquired from the building trade, gave him a back door into painting.

On these panels, which draw attention to themselves as objects in their own right - and would meet the needs of a Minimalist - he was able to realize his visual ideas in a medium that lay somewhere in a hybrid zone between drawing and oil painting.

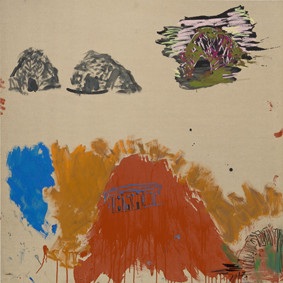

The early works on masonite may be described as open fields of experimentation where cavernous forms, individual log cabins or yurts, rays of sunshine, reminiscent of Japanese naval ensigns, or fragments of trees, now and again encounter clichés drawn from the popular culture of advertising, fashion or film.

The square panels in themselves negate the creation of any kind of tensionfilled composition, since they are already arranged on square canvases according to the varying edge lengths. Beyond that, the standardised format is suggestive of combinations arranged non-hierarchically. Kirkeby sometimes combined the panels in pairs, or in blocks of three or four, consisting of equal and interchangeable elements drawn from serial sequences. According to Lasse B.

Antonsen, this "gave Kirkeby the freedom to build references between individual paintings, while also pursuing a system of references within each individual work".3 Coming at painting in this oblique manner would become a genre in itself in Kirkeby's oeuvre; and works on masonite still very much preoccupy the artist today.

Blackboards

Towards the late 1970s, the nature of the artist's works on masonite changed fundamentally. Kirkeby started applying a black ground to the panels. These so-called blackboards were distinguishable from previous compositions, which notably lacked order, in their calmness and clarity of form and composition. Key elements of the artist's wide repertoire of forms, such as, for instance, crystalline structures, planks of wood, rock formations and even animals often appear in isolation or neatly arranged as delicate drawings within the evocative space of the blackboards. They are thus not only reminiscent of the panels executed almost coevally by Joseph Beuys and of the - aesthetically much closer - panels by Rudolf Steiner, which date from the 1920s, but they are also similar to scientific presentations of geological or biological findings, such as had been published by Ernst Haeckel in his Kunstformen der Natur in 1904.

That the blackboards make reference to the geological field studies that Kirke- by undertook between 1957 and 1966 during various expeditions to Greenland is obvious. Kirkeby's art is closely linked to scientific findings and their presentation.

In his essay, 'blackboards', he writes about the problems associated with presenting the connections between geological developments on panels for museums, and these educational deliberations of his also provide one way of accessing Kirkeby's works on masonite, "How to comprehend what is on the blackboards? When one writes 400 to 500 million years, no-one understands it anyway. No, I prefer then to draw in a comprehensible manner in pink chalk.

[...] Any representation or exhibition of geological knowledge or material is tied up with beauty after all. [...] The material settles on the panel; all of that almost invisible material from the Tertiary period. [...] But it is as if everything dissolves, taking on the nature of a sketch". (4)

Signs - knowledge - beauty - material - settling - the invisible - dissolving – this series of concepts drawn from Kirkeby's observations can be applied directly to his works on masonite, illustrating the mirroring of his theoretical process and his creative work.

Works on masonite 2011-13 - reappearance and emergence In 2011, after more than 30 years, the curtain to the rear of the forms depicted in the blackboards is raised. Kirkeby now no longer stages the objects on their dark ground. Beneath the black paint the beige-coloured, factory-produced ground consisting of fine wood fibre is exposed. Where before fine threads floating freely within a diffuse darkness were the predominant feature, now we encounter raw, recalcitrant material. In this way, Kirkeby establishes an unmediated relationship between plane and form, thus creating a new chapter for his works on masonite. The individual pictorial elements are now, it seems, left to the free play of varying forces. At times, the works seem aggressive, even wild, as if the artist has consciously put himself under pressure of time. The square image becomes the arena in which a struggle between assertion and dissolution seems to take place.

Seen against the backdrop of the development of the works on masonite as outlined, works produced since 2011 are reminiscent of the earliest panels, but also of paintings from the 1970s. Elements, such as, for instance, a garden fence, simple wooden houses or huts, references to temple complexes from of the blackboards. They are thus not only reminiscent of the panels executed almost coevally by Joseph Beuys and of the - aesthetically much closer – panels by Rudolf Steiner, which date from the 1920s, but they are also similar to scientific presentations of geological or biological findings, such as had been published by Ernst Haeckel in his Kunstformen der Natur in 1904.

That the blackboards make reference to the geological field studies that Kirke- by undertook between 1957 and 1966 during various expeditions to Greenland is obvious. Kirkeby's art is closely linked to scientific findings and their presentation.

In his essay, 'blackboards', he writes about the problems associated with presenting the connections between geological developments on panels for museums, and these educational deliberations of his also provide one way of accessing Kirkeby's works on masonite, "How to comprehend what is on the blackboards? When one writes 400 to 500 million years, no-one understands it anyway. No, I prefer then to draw in a comprehensible manner in pink chalk.

[...] Any representation or exhibition of geological knowledge or material is tied up with beauty after all. [...] The material settles on the panel; all of that almost invisible material from the Tertiary period. [...] But it is as if everything dissolves, taking on the nature of a sketch". (4)

Signs - knowledge - beauty - material - settling - the invisible - dissolving – this series of concepts drawn from Kirkeby's observations can be applied directly to his works on masonite, illustrating the mirroring of his theoretical process and his creative work. Works on masonite 2011-13 - reappearance and emergence In 2011, after more than 30 years, the curtain to the rear of the forms depicted in the blackboards is raised. Kirkeby now no longer stages the objects on their dark ground. Beneath the black paint the beige-coloured, factory-produced ground consisting of fine wood fibre is exposed. Where before fine threads floating freely within a diffuse darkness were the predominant feature, now we encounter raw, recalcitrant material. In this way, Kirkeby establishes an unmediated relationship between plane and form, thus creating a new chapter for his works on masonite. The individual pictorial elements are now, it seems, left to the free play of varying forces. At times, the works seem aggressive, even wild, as if the artist has consciously put himself under pressure of time. The square image becomes the arena in which a struggle between assertion and dissolution seems to take place.

Seen against the backdrop of the development of the works on masonite as outlined, works produced since 2011 are reminiscent of the earliest panels, but also of paintings from the 1970s. Elements, such as, for instance, a garden fence, simple wooden houses or huts, references to temple complexes from advanced South American cultures, or the typical forms of snakes or applied kitsch images allow there to be no doubt that the artist is deliberately referencing his own earlier work. This encountering of disparate forms presents the viewer with a puzzle. What is this all about?

Tree stumps and growth rings, South American pyramids, crystalline structures, layers of rock or huts of pre-historic appearance: again and again the assemblage simultaneously makes reference to early or long-lasting periods of natural and cultural history. Kirkeby appears to be intently interested in remembered images drawn from culture, nature and from his own work. Remembering and documenting, preservation and decay, recording and forgetting, these are the poles between which the artist moves. It seems as if he wishes to bind together nature and culture, things of his own and alien objects within the circus ring of his panels and simultaneously to indicate the futility of this universal endeavour.

The decisive difference from the early works on masonite comes in the almost unbridled, gestural energy which dominates the new panels. At times, the planes measuring just less than one-and-a-half square metres teem with powerful gestures, which appear to fight it out for their place and their existence. A powerful tension is thus established between patches of colour and splotches, and pools of paint, which flow into one another.

The group of works on masonite from 2011-13 exhibit a wildness of gesture inflected by chance in a manner almost unseen in Kirkeby's previous work. The form fragments of his alphabet are increasingly dispersed and seem to sink back into an elemental original state. An organic structure is thus created, being dominated by spontaneity, directness, speed and, not to be ignored: aggressivity.

Kirkeby removes clarity from his forms. The evocative gives way to the unmediated, mood yields to direct expression. The mass of a tree trunk dissolves into staccato-like outlines; a tree stump disintegrates into radial structures, and the grain of a plank of wood is perceived via the paintbrush as a gestural blow.

Compositional discipline and eruptions of energy encounter one another with new force. It appears as if the artist is challenging himself to the greatest degree, in fact, almost that he rebels against the experiences of a lifetime. Yet, here and there one perceives ordering systems in the form of lines or vertically arranged formal elements, but they are immediately made contingent again by the restless, nervous pictorial structure.

A tried and tested standard

Now at the age of 75, Kirkeby is able to look back over an enormous life's work.

The fact that the works on masonite were not just an episode in his oeuvre, but in 2013 have entered their sixth decade as a genre in themselves, underlines their importance within Kirkeby's body of work as a whole.

That the artist continues to return to the easily managed format of the panels, points to the potential of this open and yet precisely defined medium. "A painting without an intellectual framework is nothing," wrote Kirkeby in 1975.5 The square format of the panels seems in itself to represent the kind of frame that demands again and again to be filled in a dialogue between the intellect and the creative process.

The works on masonite when seen as a whole are a means of cognition, a field of experimentation, a display area for educational purposes and an arena for, and reservoir of, the artist's alphabet of objects and gestures. These pieces have taken on the role of standard works within Kirkeby's oeuvre, corresponding - when carried over into the realm of music - not to large symphonies, but rather to sonatas or fugues. The works on masonite are the serial outcomes both formally and in respect of subject matter of moments of action open in all directions.

When Kirkeby employed the hybrid medium of the panels for the first time in the 1960s as a "sort of personal compromise",6 they were the back route into that which today above all distinguishes his work, painting on a large scale. The works on masonite executed since 2011 may again be characterised as the start of something new: as the starting point of a direct, unadorned painting, which is on the way towards breaking new ground.

In one of the most recent panels a sun disk sits on a dark surface in a threatening and yet enticing manner, in a similar way to another in one of the first works on masonite of the 1960s. The circle is completed and at the same time, Kirkeby awakens new expectations in his audience.

Nils Ohlsen

Director of Old Masters and Modern Art, The National Museum of Oslo

1 Per Kirkeby, Bravura. Ausgewählte Essays, Berne/Berlin 1984, p. 28.

2 Lasse B. Antonsen, Per Kirkeby and the Art of the 1960s, Cologne/New York 1995, np.

3 Lasse B. Antonsen, op. cit., np.

4 Per Kirkeby, op. cit., pp. 212-13.

5 'Per Kirkeby: A Selection of Images', in: Lasse B. Antonsen, op. cit., np.

6 ibid, np. Untitled, 2011, [PKI-11-017

White Masonites

23 August - 28 September 2013

Per Kirkeby - works on masonite in the sixth decade

122 cm x 122 cm

Since 1965, Per Kirkeby has been producing works on hardboard – specifically on masonite - always employing the same format: 122 x 122 cm. Prior to starting to paint, Kirkeby was closely associated with the Experimental Art School in Copenhagen in 1962, at a moment when painting seemed to have lost its validity, where he was involved in video projects, happenings and Fluxus events.

Against this backdrop, it is understandable, as he himself wrote, that he felt like a traitor when, in spite of this, he painted.1 "Kirkeby continuously struggles with a feeling of not being of his time, of wishing to hold on to outmoded, outdated material".2 In this situation, masonite panels, industrially produced, far from artistic, and acquired from the building trade, gave him a back door into painting.

On these panels, which draw attention to themselves as objects in their own right - and would meet the needs of a Minimalist - he was able to realize his visual ideas in a medium that lay somewhere in a hybrid zone between drawing and oil painting.

The early works on masonite may be described as open fields of experimentation where cavernous forms, individual log cabins or yurts, rays of sunshine, reminiscent of Japanese naval ensigns, or fragments of trees, now and again encounter clichés drawn from the popular culture of advertising, fashion or film.

The square panels in themselves negate the creation of any kind of tensionfilled composition, since they are already arranged on square canvases according to the varying edge lengths. Beyond that, the standardised format is suggestive of combinations arranged non-hierarchically. Kirkeby sometimes combined the panels in pairs, or in blocks of three or four, consisting of equal and interchangeable elements drawn from serial sequences. According to Lasse B.

Antonsen, this "gave Kirkeby the freedom to build references between individual paintings, while also pursuing a system of references within each individual work".3 Coming at painting in this oblique manner would become a genre in itself in Kirkeby's oeuvre; and works on masonite still very much preoccupy the artist today.

Blackboards

Towards the late 1970s, the nature of the artist's works on masonite changed fundamentally. Kirkeby started applying a black ground to the panels. These so-called blackboards were distinguishable from previous compositions, which notably lacked order, in their calmness and clarity of form and composition. Key elements of the artist's wide repertoire of forms, such as, for instance, crystalline structures, planks of wood, rock formations and even animals often appear in isolation or neatly arranged as delicate drawings within the evocative space of the blackboards. They are thus not only reminiscent of the panels executed almost coevally by Joseph Beuys and of the - aesthetically much closer - panels by Rudolf Steiner, which date from the 1920s, but they are also similar to scientific presentations of geological or biological findings, such as had been published by Ernst Haeckel in his Kunstformen der Natur in 1904.

That the blackboards make reference to the geological field studies that Kirke- by undertook between 1957 and 1966 during various expeditions to Greenland is obvious. Kirkeby's art is closely linked to scientific findings and their presentation.

In his essay, 'blackboards', he writes about the problems associated with presenting the connections between geological developments on panels for museums, and these educational deliberations of his also provide one way of accessing Kirkeby's works on masonite, "How to comprehend what is on the blackboards? When one writes 400 to 500 million years, no-one understands it anyway. No, I prefer then to draw in a comprehensible manner in pink chalk.

[...] Any representation or exhibition of geological knowledge or material is tied up with beauty after all. [...] The material settles on the panel; all of that almost invisible material from the Tertiary period. [...] But it is as if everything dissolves, taking on the nature of a sketch". (4)

Signs - knowledge - beauty - material - settling - the invisible - dissolving – this series of concepts drawn from Kirkeby's observations can be applied directly to his works on masonite, illustrating the mirroring of his theoretical process and his creative work.

Works on masonite 2011-13 - reappearance and emergence In 2011, after more than 30 years, the curtain to the rear of the forms depicted in the blackboards is raised. Kirkeby now no longer stages the objects on their dark ground. Beneath the black paint the beige-coloured, factory-produced ground consisting of fine wood fibre is exposed. Where before fine threads floating freely within a diffuse darkness were the predominant feature, now we encounter raw, recalcitrant material. In this way, Kirkeby establishes an unmediated relationship between plane and form, thus creating a new chapter for his works on masonite. The individual pictorial elements are now, it seems, left to the free play of varying forces. At times, the works seem aggressive, even wild, as if the artist has consciously put himself under pressure of time. The square image becomes the arena in which a struggle between assertion and dissolution seems to take place.

Seen against the backdrop of the development of the works on masonite as outlined, works produced since 2011 are reminiscent of the earliest panels, but also of paintings from the 1970s. Elements, such as, for instance, a garden fence, simple wooden houses or huts, references to temple complexes from of the blackboards. They are thus not only reminiscent of the panels executed almost coevally by Joseph Beuys and of the - aesthetically much closer – panels by Rudolf Steiner, which date from the 1920s, but they are also similar to scientific presentations of geological or biological findings, such as had been published by Ernst Haeckel in his Kunstformen der Natur in 1904.

That the blackboards make reference to the geological field studies that Kirke- by undertook between 1957 and 1966 during various expeditions to Greenland is obvious. Kirkeby's art is closely linked to scientific findings and their presentation.

In his essay, 'blackboards', he writes about the problems associated with presenting the connections between geological developments on panels for museums, and these educational deliberations of his also provide one way of accessing Kirkeby's works on masonite, "How to comprehend what is on the blackboards? When one writes 400 to 500 million years, no-one understands it anyway. No, I prefer then to draw in a comprehensible manner in pink chalk.

[...] Any representation or exhibition of geological knowledge or material is tied up with beauty after all. [...] The material settles on the panel; all of that almost invisible material from the Tertiary period. [...] But it is as if everything dissolves, taking on the nature of a sketch". (4)

Signs - knowledge - beauty - material - settling - the invisible - dissolving – this series of concepts drawn from Kirkeby's observations can be applied directly to his works on masonite, illustrating the mirroring of his theoretical process and his creative work. Works on masonite 2011-13 - reappearance and emergence In 2011, after more than 30 years, the curtain to the rear of the forms depicted in the blackboards is raised. Kirkeby now no longer stages the objects on their dark ground. Beneath the black paint the beige-coloured, factory-produced ground consisting of fine wood fibre is exposed. Where before fine threads floating freely within a diffuse darkness were the predominant feature, now we encounter raw, recalcitrant material. In this way, Kirkeby establishes an unmediated relationship between plane and form, thus creating a new chapter for his works on masonite. The individual pictorial elements are now, it seems, left to the free play of varying forces. At times, the works seem aggressive, even wild, as if the artist has consciously put himself under pressure of time. The square image becomes the arena in which a struggle between assertion and dissolution seems to take place.

Seen against the backdrop of the development of the works on masonite as outlined, works produced since 2011 are reminiscent of the earliest panels, but also of paintings from the 1970s. Elements, such as, for instance, a garden fence, simple wooden houses or huts, references to temple complexes from advanced South American cultures, or the typical forms of snakes or applied kitsch images allow there to be no doubt that the artist is deliberately referencing his own earlier work. This encountering of disparate forms presents the viewer with a puzzle. What is this all about?

Tree stumps and growth rings, South American pyramids, crystalline structures, layers of rock or huts of pre-historic appearance: again and again the assemblage simultaneously makes reference to early or long-lasting periods of natural and cultural history. Kirkeby appears to be intently interested in remembered images drawn from culture, nature and from his own work. Remembering and documenting, preservation and decay, recording and forgetting, these are the poles between which the artist moves. It seems as if he wishes to bind together nature and culture, things of his own and alien objects within the circus ring of his panels and simultaneously to indicate the futility of this universal endeavour.

The decisive difference from the early works on masonite comes in the almost unbridled, gestural energy which dominates the new panels. At times, the planes measuring just less than one-and-a-half square metres teem with powerful gestures, which appear to fight it out for their place and their existence. A powerful tension is thus established between patches of colour and splotches, and pools of paint, which flow into one another.

The group of works on masonite from 2011-13 exhibit a wildness of gesture inflected by chance in a manner almost unseen in Kirkeby's previous work. The form fragments of his alphabet are increasingly dispersed and seem to sink back into an elemental original state. An organic structure is thus created, being dominated by spontaneity, directness, speed and, not to be ignored: aggressivity.

Kirkeby removes clarity from his forms. The evocative gives way to the unmediated, mood yields to direct expression. The mass of a tree trunk dissolves into staccato-like outlines; a tree stump disintegrates into radial structures, and the grain of a plank of wood is perceived via the paintbrush as a gestural blow.

Compositional discipline and eruptions of energy encounter one another with new force. It appears as if the artist is challenging himself to the greatest degree, in fact, almost that he rebels against the experiences of a lifetime. Yet, here and there one perceives ordering systems in the form of lines or vertically arranged formal elements, but they are immediately made contingent again by the restless, nervous pictorial structure.

A tried and tested standard

Now at the age of 75, Kirkeby is able to look back over an enormous life's work.

The fact that the works on masonite were not just an episode in his oeuvre, but in 2013 have entered their sixth decade as a genre in themselves, underlines their importance within Kirkeby's body of work as a whole.

That the artist continues to return to the easily managed format of the panels, points to the potential of this open and yet precisely defined medium. "A painting without an intellectual framework is nothing," wrote Kirkeby in 1975.5 The square format of the panels seems in itself to represent the kind of frame that demands again and again to be filled in a dialogue between the intellect and the creative process.

The works on masonite when seen as a whole are a means of cognition, a field of experimentation, a display area for educational purposes and an arena for, and reservoir of, the artist's alphabet of objects and gestures. These pieces have taken on the role of standard works within Kirkeby's oeuvre, corresponding - when carried over into the realm of music - not to large symphonies, but rather to sonatas or fugues. The works on masonite are the serial outcomes both formally and in respect of subject matter of moments of action open in all directions.

When Kirkeby employed the hybrid medium of the panels for the first time in the 1960s as a "sort of personal compromise",6 they were the back route into that which today above all distinguishes his work, painting on a large scale. The works on masonite executed since 2011 may again be characterised as the start of something new: as the starting point of a direct, unadorned painting, which is on the way towards breaking new ground.

In one of the most recent panels a sun disk sits on a dark surface in a threatening and yet enticing manner, in a similar way to another in one of the first works on masonite of the 1960s. The circle is completed and at the same time, Kirkeby awakens new expectations in his audience.

Nils Ohlsen

Director of Old Masters and Modern Art, The National Museum of Oslo

1 Per Kirkeby, Bravura. Ausgewählte Essays, Berne/Berlin 1984, p. 28.

2 Lasse B. Antonsen, Per Kirkeby and the Art of the 1960s, Cologne/New York 1995, np.

3 Lasse B. Antonsen, op. cit., np.

4 Per Kirkeby, op. cit., pp. 212-13.

5 'Per Kirkeby: A Selection of Images', in: Lasse B. Antonsen, op. cit., np.

6 ibid, np. Untitled, 2011, [PKI-11-017