Armen Eloyan: Bees left it or bears do it

30 May - 25 Jul 2009

Armen Eloyan, Left Overs, 2008, Wood, plaster, carton, textile, ink acrylic paint, unique, sculpture 83 x 45 x 38 cm

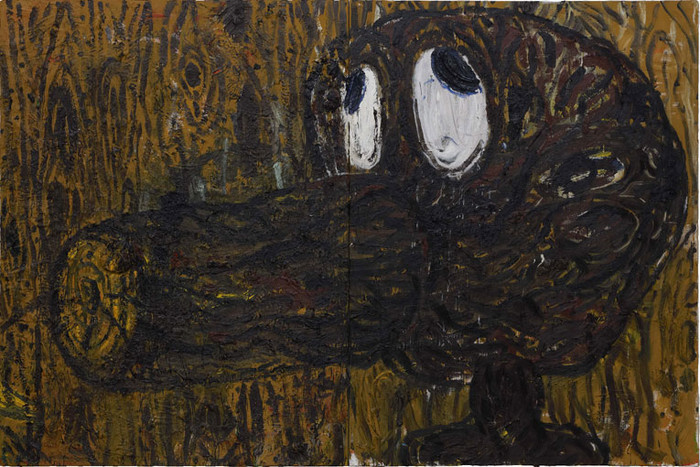

With “Bees left it or bears do it”, Galerie Bob van Orsouw is devoting their second solo exhibition to the Armenian artist Armen Eloyan (*1966) after his works have, in the meantime, been presented at the institutions of the Kunsthalle St. Gallen (2008) and the Parasol Unit in London (2007). Comic figures still play a central role. Although the motifs call up an allusion to Pop Art, the artists that Armen Eloyan in fact holds in honor are found among the Abstract Expressionists, especially those who have mastered the balance between figurative and abstract painting, like De Kooning and Guston. In contrast to earlier paintings, Eloyan’s palette has brightened and his brushwork opened up. Both facts give us an overall liberated impression. The luminous colors are, in part, squeezed directly out of the tube onto the canvas; contours vanish, figure and ground merge all the way to abstraction.

The almost ‘zoological’ accumulation of anthropomorphized figures from the realm of comic-strip animals—hung in the studio like a row of ancestors together with representatives from fairytales, legends and sagas—open up different interpretational perspectives. The most important of these make up the artist’s involvement with current mythological placeholders: Eloyan’s own Noah’s ark with cats (Krazy Kat), dogs (Goofy), ducks (Donald), mice (Mickey, Minnie), frogs (Kermit), pigs (The Three Little Pigs) or rabbits (Bugs Bunny) all derive from subcultures and degraded myths in an era of a ubiquitous Disney fixation. Comic heroes have long since replaced gods, become mediators of universal archetypes and serve as projection screens for our experiences. Their individual nature is so very present to us that a whole range of human destinies can be easily evoked (such as Popeye’s courage or Pinocchio’s lies). This is all the more so when the pictoriality of cartoons becomes an advantage over the oral traditions of fairytales or folkloric storytelling, highlighting the comic-strip’s immediate, pictorial overview and a subsequent cascade of associations.

The fact that the subject is quickly understandable in combination with its often fictitious narrative character allows us to focus on the formal qualities of Eloyan’s stupendous compositions: powerful painting, a ‘tour de force’ whose almost sculptural forms seem to rise up like the outbreak of a volcano from tectonic depths before the masses of viscous and oily paint solidify on the canvas with a somewhat softer crust. And yet no step in the choreography of this painting performance is left to chance; it is guided by assured intuition and art’s predecessors. The present, likewise for Eloyan, is grounded in the past, even if—during a conversation on vanitas symbols in art history—he poses the simple question: These pictures exist already; why should I paint a skull too? Therefore his reply in paint does not surprise us: a series of still lifes with orange-colored, hollowed-out and grimacing Halloween pumpkins. They are mere proxies for a celebration, whose almost forgotten reference to death is avoided in our present-day society, a celebration which has become a commercialized masquerade.

Adrian Ciurea, rheumatologist and collector

The almost ‘zoological’ accumulation of anthropomorphized figures from the realm of comic-strip animals—hung in the studio like a row of ancestors together with representatives from fairytales, legends and sagas—open up different interpretational perspectives. The most important of these make up the artist’s involvement with current mythological placeholders: Eloyan’s own Noah’s ark with cats (Krazy Kat), dogs (Goofy), ducks (Donald), mice (Mickey, Minnie), frogs (Kermit), pigs (The Three Little Pigs) or rabbits (Bugs Bunny) all derive from subcultures and degraded myths in an era of a ubiquitous Disney fixation. Comic heroes have long since replaced gods, become mediators of universal archetypes and serve as projection screens for our experiences. Their individual nature is so very present to us that a whole range of human destinies can be easily evoked (such as Popeye’s courage or Pinocchio’s lies). This is all the more so when the pictoriality of cartoons becomes an advantage over the oral traditions of fairytales or folkloric storytelling, highlighting the comic-strip’s immediate, pictorial overview and a subsequent cascade of associations.

The fact that the subject is quickly understandable in combination with its often fictitious narrative character allows us to focus on the formal qualities of Eloyan’s stupendous compositions: powerful painting, a ‘tour de force’ whose almost sculptural forms seem to rise up like the outbreak of a volcano from tectonic depths before the masses of viscous and oily paint solidify on the canvas with a somewhat softer crust. And yet no step in the choreography of this painting performance is left to chance; it is guided by assured intuition and art’s predecessors. The present, likewise for Eloyan, is grounded in the past, even if—during a conversation on vanitas symbols in art history—he poses the simple question: These pictures exist already; why should I paint a skull too? Therefore his reply in paint does not surprise us: a series of still lifes with orange-colored, hollowed-out and grimacing Halloween pumpkins. They are mere proxies for a celebration, whose almost forgotten reference to death is avoided in our present-day society, a celebration which has become a commercialized masquerade.

Adrian Ciurea, rheumatologist and collector