Gabríela Fridriksdóttir "ouroboros"

29 Mar - 17 May 2008

Gabriela Fridriksdottir

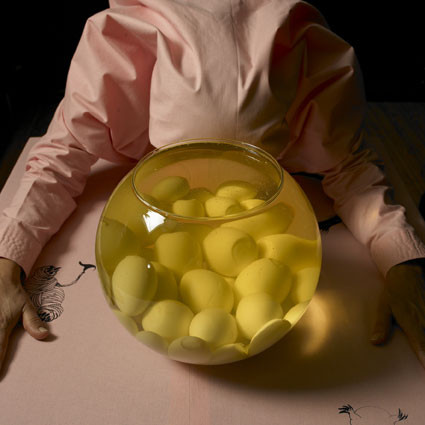

Still from “Ouroboros”, 2007

Video

15 minutes

Edition of 5 (+1 AP)

Courtesy Bob van Orsouw Gallery, Zurich

Still from “Ouroboros”, 2007

Video

15 minutes

Edition of 5 (+1 AP)

Courtesy Bob van Orsouw Gallery, Zurich

The Icelandic artist Gabríela Friđriksdóttir (*1971) lives and works in Reykjavik. Since her participation in the Venice Biennale (Icelandic Pavilion 2005) with her installation “Versations/Tetralógica” as well as her spacious exhibition at the Migros Museum of Contemporary Art in Zurich (2006), her work has attracted international attention. For the first time in Switzerland, Galerie Bob van Orsouw is showing her newest film “Ouroboros” within the framework of a solo exhibition. The presentation is a followup to the group exhibition “Through the Looking Glass”, in which Friđriksdóttir’s enigmatic ink drawings were introduced.

Her drawings not only represent the starting point for exploring other media (painting, sculpture and film), it combines with these to a pictorial vocabulary that uses narrative material while simultaneously disallowing any kind of linear storyline. The basic emotions of fear and isolation that constitute the human psyche, as well as the question of the origin and meaning of existence, are set in the context of Nordic sagas and creational myths. The film title “Ouroboros” takes up the cross-cultural symbol of the primal snake swallowing his tail. This infinite return of death and rebirth embodied by the snake is what Friđriksdóttir has called: “the eternal cycle of renewal, the creation out of destruction”.

In analogy to her earlier work cycle “Inside the Core”, in which the number eight was the dominant feature in content and form, “Ouroboros” is also furnished with numerological references. The seven vertebrae of the primal snake make up the film’s numerical framework and its leitmotif. In seven scenes against the backdrop of Iceland’s natural beauty, actions take place that run from mystical to surreal and often to grotesque extremes. Thus at the climax of the film, Sybille—who via her mouth gives birth to black stones—meets the majestic figure of death. In another scene, the memories of an old couple are laid over their bodies in the form of fine white flour, as though it were the concrete emanation of their souls. In another episode, two cannibalistic creatures are seated in a cave, indulging in their cravings. As in a B horror movie, their heads are shaped out of raw flesh. This scene, driven by animal instincts and violence, stands out against the subtle poetic plot in another section of the film. A woman sprinkles drops of ink onto a loaf of bread that she then shoves into the oven. Bread also appears as a leitmotif in earlier works and, as in other materials (e.g., dried whole fish), points to symbolic and metaphorical associations.

In “Ouroboros”, what is crudely archaic encounters technical perfection and an impeccable film aesthetic. Paradox seems to be the policy. It is not only the chaos of human feelings that contrasts with the undisturbed breadth of the Icelandic landscape. Also the protagonist’s existential angst stands in unresolvable contradiction to the cosmic state of affairs. In contrast to the film, the exhibited drawings and paintings in their reduction have an almost abstractly graphic look. It is the sculpture—a table on which objects from the movie have been arranged—with its haptic quality that first arouses associations of single film sequences. Friđriksdóttir resembles a magician. With her codified pictorial vocabulary that invokes traditional genesis myths, she constructs a reality in which dream and ratio, the occult and the factual, are fused into a fantastical amalgam.

Birgid Uccia

Her drawings not only represent the starting point for exploring other media (painting, sculpture and film), it combines with these to a pictorial vocabulary that uses narrative material while simultaneously disallowing any kind of linear storyline. The basic emotions of fear and isolation that constitute the human psyche, as well as the question of the origin and meaning of existence, are set in the context of Nordic sagas and creational myths. The film title “Ouroboros” takes up the cross-cultural symbol of the primal snake swallowing his tail. This infinite return of death and rebirth embodied by the snake is what Friđriksdóttir has called: “the eternal cycle of renewal, the creation out of destruction”.

In analogy to her earlier work cycle “Inside the Core”, in which the number eight was the dominant feature in content and form, “Ouroboros” is also furnished with numerological references. The seven vertebrae of the primal snake make up the film’s numerical framework and its leitmotif. In seven scenes against the backdrop of Iceland’s natural beauty, actions take place that run from mystical to surreal and often to grotesque extremes. Thus at the climax of the film, Sybille—who via her mouth gives birth to black stones—meets the majestic figure of death. In another scene, the memories of an old couple are laid over their bodies in the form of fine white flour, as though it were the concrete emanation of their souls. In another episode, two cannibalistic creatures are seated in a cave, indulging in their cravings. As in a B horror movie, their heads are shaped out of raw flesh. This scene, driven by animal instincts and violence, stands out against the subtle poetic plot in another section of the film. A woman sprinkles drops of ink onto a loaf of bread that she then shoves into the oven. Bread also appears as a leitmotif in earlier works and, as in other materials (e.g., dried whole fish), points to symbolic and metaphorical associations.

In “Ouroboros”, what is crudely archaic encounters technical perfection and an impeccable film aesthetic. Paradox seems to be the policy. It is not only the chaos of human feelings that contrasts with the undisturbed breadth of the Icelandic landscape. Also the protagonist’s existential angst stands in unresolvable contradiction to the cosmic state of affairs. In contrast to the film, the exhibited drawings and paintings in their reduction have an almost abstractly graphic look. It is the sculpture—a table on which objects from the movie have been arranged—with its haptic quality that first arouses associations of single film sequences. Friđriksdóttir resembles a magician. With her codified pictorial vocabulary that invokes traditional genesis myths, she constructs a reality in which dream and ratio, the occult and the factual, are fused into a fantastical amalgam.

Birgid Uccia