Marcel van Eeden

22 Mar - 31 May 2014

© Marcel van Eeden

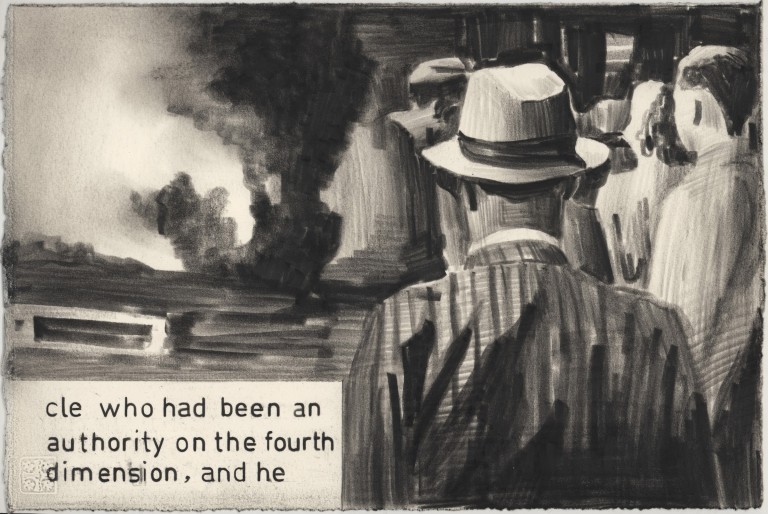

From the Series The Fourth-Dimensional Demonstrator (3/9), 2012

Nero pencil on paper

19 x 28 cm / 7 1/2 x 11 inches

From the Series The Fourth-Dimensional Demonstrator (3/9), 2012

Nero pencil on paper

19 x 28 cm / 7 1/2 x 11 inches

MARCEL VAN EEDEN

Particles of grain, and earth, and air, and rain

22 March – 31 May 2014

‘To have a home is to become vulnerable. Not just to the attacks of others, but to our own adventures in alienation’ observes literary critic James Wood. Yet migration and movement are the norm in our time. The person who lives their life in just one place is now the exception, if historically the rule. Wood calls the homelessness of the contemporary migrant, those of us who have chosen to leave home, be that for study, work, or the straightforward desire to see more of the world, ‘secular homelessness’.1 If and when we return home, that home is unlikely to be the same place we left. But should we stay? Probably not. ‘Secular homelessness... might be the inevitable ordinary state. Secular homelessness is not just what will always occur in Eden, but what should occur, again and again.’

Marcel van Eeden’s new works mark a return to his birthplace. He documented Den Haag before, earlier in his career, but not at this scale. Large works in black oil pastels present street scenes: a view from under a railway bridge; a boulevard; a large building observed from a distance, lights burning in its windows. In the same series a dense pattern of leaves and flowers - wallpaper or a curtain - is described in line, calling to mind a stifling bourgeois interior, and in another work the message ‘UTMOST IMPORTANCE’, in thick characters, crowds into the top right hand corner of the otherwise blank sheet. Scrawled writing over the landscapes appears to date the works, or make reference to events of 1930, 1939 and maybe that says 1950? Van Eeden was born in 1965 and has consistently created bodies of work that document events or lives prior to his birth. Some of these reproduce true histories, some are inventions and several combine the two. Nonetheless, they are always experiences the artist could not have direct knowledge of, so how can they be classified?

A brief glance at the artist’s drawings might suggest nostalgia, given the largely black and white palette and film noir-ish framing and lighting. Nowadays nostalgia is a subject of derision, seen as a weakness, wasteful indulgence or regressive. Svetlana Boym identifies it as a ‘guilt free homecoming, an ethical and aesthetic failure...The nostalgic desires to obliterate history and turn it into private or collective mythology, to revisit time like space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition.’2 It is clear that van Eeden also refuses to surrender to the irreversibility of time, though he also refuses to acknowledge the recorded past’s fixedness. His approach is not the relativism of historicism but an alchemy that liberally blends plausible and impossible histories. The admixture is not always evident, some works seem vaguely anachronous, other scenes are feasible (that van Eeden’s protagonist Oswald Sollman stood before the Pergamon Altar as recorded in the series Die Archäologe. Die Reisen des Oswald Sollmann (The Archeologist. The Travels of Oswald Sollmann, 2006-2008), for instance) and others clearly test the viewer’s credulity (a caption in the series K.M. Wiegand Life and Work (2005) states that the protagonist married Elizabeth Taylor). And van Eeden does not work exclusively in a documentary format; other works embrace the absurd and surrealistic (A Cutlet Vaudeville Show, 2010) or detective fiction (The Zurich Trial Part 1: Witness for the Prosecution, 2008-9). Text within these drawings, in the form of captions or speech bubbles, obfuscates as frequently as it clarifies, and nearly always provokes at least two layers of reading.

If van Eeden’s most recent works seem, in comparison, simpler, by now he has taught us to distrust simplicity. Over the course of his career to date, social media platforms have also become extraordinarily prevalent. Now we use Instagram filters to render the current day decades older; as Nathan Jurgensen has written ‘social media have invited users to adopt a sort of documentary vision, through which the present is always apprehended as a potential past’.3 Maybe as an act of resistance to this ‘discovery’ of the old look and the nostalgic present, the filters van Eeden uses propose a past not as a site for comforting reminiscence, but excavation. Den Haag has been observed, and those observations in turn examined, written over, considered for their architectural merits, perhaps the next stages in their history inscribed upon them. It is not hindsight, for it never was, but those dark shadows under the bridge do not reassure.

Aoife Rosenmeyer

Marcel van Eeden was born in The Hague, The Netherlands in 1965, he lives and works in Zurich and The Hague. In 2013 he won the Ouborgprijs, Den Haag; Major Solo Exhibitions: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel (2014), Institut Mathildenhöhe, Darmstadt (2011); Kunstmuseum St. Gallen (2011); Galerie Bob van Orsouw (2014, 2010, 2007); Haus am Waldsee, Berlin (2010); Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (2009); Centraal Museum, Utrecht (2008); Gemeentemuseum GEM, The Hague (2003). International Group Exhibitions a.o.: Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin (2011); Kunstmuseum Bonn (2010); Magasin 3 / Stockholm Konsthall (2010); Kestnergesellschaft, Hannover (2007); 4th Berlin Biennial for contemporary art (2006).

1 James Wood, ‘On Not Going Home’, London Review of Books, Volume 36 Number 4, 20 February 2014

2 Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York, NY: Basic Books), 2001

3 Nathan Jurgensen, ‘Pics and It Didn’t Happen’, The New Enquiry, 7 February 2013, http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/pics-and-it-didnt-happen/

Particles of grain, and earth, and air, and rain

22 March – 31 May 2014

‘To have a home is to become vulnerable. Not just to the attacks of others, but to our own adventures in alienation’ observes literary critic James Wood. Yet migration and movement are the norm in our time. The person who lives their life in just one place is now the exception, if historically the rule. Wood calls the homelessness of the contemporary migrant, those of us who have chosen to leave home, be that for study, work, or the straightforward desire to see more of the world, ‘secular homelessness’.1 If and when we return home, that home is unlikely to be the same place we left. But should we stay? Probably not. ‘Secular homelessness... might be the inevitable ordinary state. Secular homelessness is not just what will always occur in Eden, but what should occur, again and again.’

Marcel van Eeden’s new works mark a return to his birthplace. He documented Den Haag before, earlier in his career, but not at this scale. Large works in black oil pastels present street scenes: a view from under a railway bridge; a boulevard; a large building observed from a distance, lights burning in its windows. In the same series a dense pattern of leaves and flowers - wallpaper or a curtain - is described in line, calling to mind a stifling bourgeois interior, and in another work the message ‘UTMOST IMPORTANCE’, in thick characters, crowds into the top right hand corner of the otherwise blank sheet. Scrawled writing over the landscapes appears to date the works, or make reference to events of 1930, 1939 and maybe that says 1950? Van Eeden was born in 1965 and has consistently created bodies of work that document events or lives prior to his birth. Some of these reproduce true histories, some are inventions and several combine the two. Nonetheless, they are always experiences the artist could not have direct knowledge of, so how can they be classified?

A brief glance at the artist’s drawings might suggest nostalgia, given the largely black and white palette and film noir-ish framing and lighting. Nowadays nostalgia is a subject of derision, seen as a weakness, wasteful indulgence or regressive. Svetlana Boym identifies it as a ‘guilt free homecoming, an ethical and aesthetic failure...The nostalgic desires to obliterate history and turn it into private or collective mythology, to revisit time like space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition.’2 It is clear that van Eeden also refuses to surrender to the irreversibility of time, though he also refuses to acknowledge the recorded past’s fixedness. His approach is not the relativism of historicism but an alchemy that liberally blends plausible and impossible histories. The admixture is not always evident, some works seem vaguely anachronous, other scenes are feasible (that van Eeden’s protagonist Oswald Sollman stood before the Pergamon Altar as recorded in the series Die Archäologe. Die Reisen des Oswald Sollmann (The Archeologist. The Travels of Oswald Sollmann, 2006-2008), for instance) and others clearly test the viewer’s credulity (a caption in the series K.M. Wiegand Life and Work (2005) states that the protagonist married Elizabeth Taylor). And van Eeden does not work exclusively in a documentary format; other works embrace the absurd and surrealistic (A Cutlet Vaudeville Show, 2010) or detective fiction (The Zurich Trial Part 1: Witness for the Prosecution, 2008-9). Text within these drawings, in the form of captions or speech bubbles, obfuscates as frequently as it clarifies, and nearly always provokes at least two layers of reading.

If van Eeden’s most recent works seem, in comparison, simpler, by now he has taught us to distrust simplicity. Over the course of his career to date, social media platforms have also become extraordinarily prevalent. Now we use Instagram filters to render the current day decades older; as Nathan Jurgensen has written ‘social media have invited users to adopt a sort of documentary vision, through which the present is always apprehended as a potential past’.3 Maybe as an act of resistance to this ‘discovery’ of the old look and the nostalgic present, the filters van Eeden uses propose a past not as a site for comforting reminiscence, but excavation. Den Haag has been observed, and those observations in turn examined, written over, considered for their architectural merits, perhaps the next stages in their history inscribed upon them. It is not hindsight, for it never was, but those dark shadows under the bridge do not reassure.

Aoife Rosenmeyer

Marcel van Eeden was born in The Hague, The Netherlands in 1965, he lives and works in Zurich and The Hague. In 2013 he won the Ouborgprijs, Den Haag; Major Solo Exhibitions: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel (2014), Institut Mathildenhöhe, Darmstadt (2011); Kunstmuseum St. Gallen (2011); Galerie Bob van Orsouw (2014, 2010, 2007); Haus am Waldsee, Berlin (2010); Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (2009); Centraal Museum, Utrecht (2008); Gemeentemuseum GEM, The Hague (2003). International Group Exhibitions a.o.: Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin (2011); Kunstmuseum Bonn (2010); Magasin 3 / Stockholm Konsthall (2010); Kestnergesellschaft, Hannover (2007); 4th Berlin Biennial for contemporary art (2006).

1 James Wood, ‘On Not Going Home’, London Review of Books, Volume 36 Number 4, 20 February 2014

2 Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York, NY: Basic Books), 2001

3 Nathan Jurgensen, ‘Pics and It Didn’t Happen’, The New Enquiry, 7 February 2013, http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/pics-and-it-didnt-happen/