Threat

07 May - 31 Jul 2011

THREAT

Group Show

7 May - 31 July, 2011

Evelyne Axell, Maria Bartuszova, Louise Bourgeois, Audrey Capel Doray, Ruth Francken, Carolee Schneemann, Penny Slinger, Marjorie Strider, Toyen

This show presents work of women artists which - by no means - can be simply grouped under one category, - and surely the notion of surrealism has still a mildly painful association to some as it was a style which even at its dawn in modernism was never fully accepted among the progressive avant-gardes.

Surrealism is often regarded for holding an alliance with kitsch and the sentimental, its suspect to introversion, and of building on non-progressive definitive forms and exaggerated naturalistic images. Thus, the politics of Surrealism were often obscured, even as its forms border on the confrontational language of Dada and the protagonists of the pre- and postwar movement were often politically active, e.g. as members of Communist organizations or as anarchists.

In the spectrum of its ambivalent reception surrealism could also be regarded as an inherently effeminate art form. It definitely offered a particular potential of radical articulation for women artists throughout.

The immediacy and efficiency of surrealist language, the often blunt and daring eroticism, the realism of 'objet trouvé', and its precise expressions of maximum evocative strengths, provide a genuine terrain for women artists' (proto)-feminist - and in a wider perspective politically engaged language.

This show further juxtaposes works by Eastern European artists next to the work of Western European and American artists from the same mostly post-war period. We see works of lesser known, or to date almost entirely overlooked artists next to works, which are more prominent to the US public's memory. Despite the political divisions of the iron curtain and the Cold War, we see astonishing familiarities in expression and themes, as well as interesting distinctions. The radical internationalism of the pre-war avant-garde made it easy to espouse a non- national movement such as surrealism. After the war, surrealism continued to appear in new updated forms, yet at times socially and geographically disconnected. Surrealist language lived on in numerous forms and ways, often leading to new art movements such as Fluxus and Pop Art or fusing with radically contemporary forms.

In a focus show we present 11 works of Polish photographer Zofia Rydet whose work has not been shown for a long time and was recently rediscovered by the Warsaw based gallery Asymetria. Rydet created a fascinating series of photomontages titled "The World of Feelings and Imagination" from the 1960s-70s advancing surreal and Dadaist motifs, while she also worked in photo reportage inspired by the meta-national show "The Family of Man" which came to Warsaw in 1955.

Rydet's motifs such as the "Mannequins" and "Threat" have an obscure take on the post-war period in images where a soldier in a uniform more reminiscent of World War I (and therefore enhancing the stylistic reference to Dada) makes his appearance in abandoned alleys and ruins, his body de-collaged into a crippled ghostlike pose.

In other photomontages we see stripped mannequins gathering in desolate post- apocalyptic landscapes possibly hinting to the threat of nuclear destruction in the Cold War time. In other motifs Rydet invented a peculiar travesty by applying 'masks' of a woman and a man with eerily deformed faces to the bodies of female and male protagonists positioned in oppressive domestic milieus and in nostalgic rural scenes, which seem to be taken from Rydet's reportage work. In some cases the stone-faced introvert female mask is attached to a male body creating a subtext of androgyny in social milieus, which seems too geographically remote and anachronistic for such manipulations of gender masquerade. These works have a truly unfamiliar atmosphere where sensations of tenderness, violence and alienation are kept in an impenetrable balance.

Rydet's work owns "a certain kind of understatement, an unexpected transition of vision. Inspired by that naïve iconography and simple minded narration, by primitive religiousness and atmosphere of folk adages and the memory of war – we enter the world of her own surreality." (Ursula Czartoryska)

Belgian artist Evelyne Axell was tutored by Surrealist and friend René Magritte and developed her own contemporary style of Pop-Surrealism. Her early work "The Erotic Machine or Concept of Boy Art"("Mec Art"), 1964, was painted programmatically 'in the style of Magritte' and mocks the Duchampian idea of the erotic machine.

In "Cercle Vicieux (Rouge)" from 1968 Axell further responds to Duchamp's concept of the isolated gender zones and the self-indulged activities of the bride and bachelors in his seminal work, the "Large Glass": in her imposing circular relief painting we see a monolithic female torso of walking legs occupying the pictorial realm, the figure being encapsulated in a red 'vicious circle', self-contained and undefined in its direction.

Marjorie Strider moved from Pop Art's joyful painterly optimism to intrusive assemblage work with colored foam as in the site-specific installation "Stair Pour" (976) at the University Graduate Center, New York. Strider worked with the foam material in ample ways from sculptural assemblage to relief paintings and drawings.

The most political variation of the foam series appears in the gouache drawing "Lady Liberty" (1972), where blue foam is pouring out of the crown of the Statue of Liberty, a still pre-trauma 1970s Pop vision of national 'threat'.

Canadian artist Audrey Capel Doray revisited the Dadaist 'Automaton' in a new Pop-language in her signature piece of the "Armored Lady"(1968). There is a sound piece of experimental jazz integrated into the iconic piece composed by Mark Oliver and the artist herself. The bust lights up in a fast rhythm exposing a text collage with notions such as "True", "East" and "West".

Around the same time British artist Penny Slinger (who today lives in California) created resin sculptures of body casts such as "Golden Triangle" (1976) and the eerie dark earlier sculpture "Bride in the Bath" (1969), a real bath tub in which a life size female figure lies covered in a full body black veil.

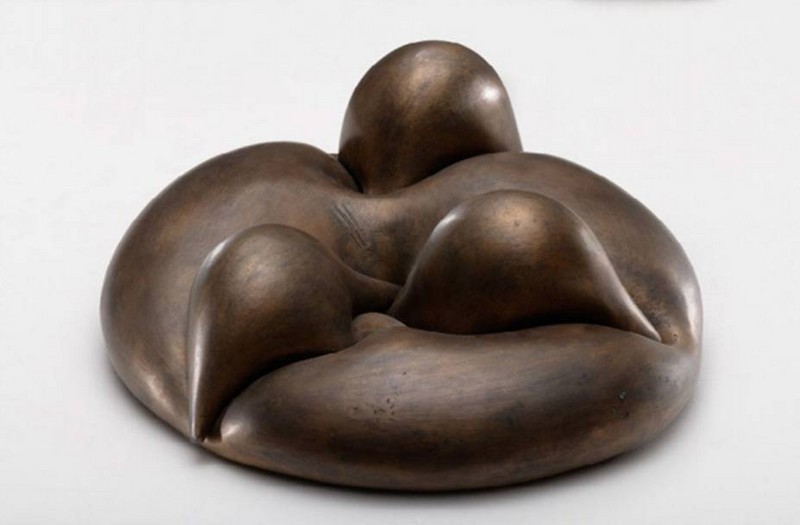

Parallel to Louise Bourgeois' abstracted phallic forms such as "Untitled (Sleep II)" and Alina Szapoznikow's body casts and semi-abstract corporeal landscapes, Czech sculptor Maria Bartuszova developed sculptures of "bionical" abstraction. While her style is more minimal and less corporeal it is nonetheless fetishistic. Although Bartuszova was one of the widely talked about rediscoveries of the last Documenta XII, her groundbreaking work remained to date relatively unknown in the US.

Like the Polish Alina Szapocznikow in the late 1960s and early 70s, the Prague- born, later American and French resident Ruth Francken, kept her outstanding style and important aesthetic distance to the ruling Parisian movement of "Nouveau Realism". Apart from her design classic of the "Homme, Chaise" (1970) (for which she took a full body cast of a young man, as Szapocznikow did from the body of her son Piotr in 1971), her work is hardly known anymore, although she (as well as her Polish contemporary) received an early solo exhibition in the Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (both under curator Suzanne Page). She was prominently associated and courted by the Parisian nobility of intellectuals. Her work presented a genuine fusion of exaggerated Pop sensibility in black & white and feminist surreal interventionism such as in the object "Televenus" (1969) and the photo-relief "Lilith" (1970).

There is a deep involvement and far reach of political expression in the work of particularly women artists of the classic period of Surrealism and Dadaism, and one finds an extraordinary richness of expression in women artists' works in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, revisiting surrealist and Dadaist styles, techniques and tropes for their contemporary aesthetic, political intentions and urgencies.

During the war in 1944 first generation Surrealist Toyen created a series of etchings titled "Cache-toi guerre!" ("Collapse war!"). The experience of the war appears in the manner of this "intensified truth" which we later find in the photomontages of Zofia Rydet and in the work of Carolee Schneemann. The style, which draws directly on current political atrocities finds at the same time a language transcending the political into a more general insight in its makings and inner operations.

The familiarities in techniques and even themes of these photomontages with Schneemann's "Illinois Central" (1968) for example and Penny Slinger's collages from the series "An Exorcism" (1977) are striking. In "Illinois Central" we see an epic panorama of rural American landscape over which a female nude in archaic rags is floating like a death angel associating once more the nuclear destruction or the images of Napal bombing in the Vietnam. In her performance "Snows", 1967, Schneemann developed a complex "Kinetic Theater" about her outrage about the Vietnam atrocities.

In Schneemann's kinetic video installation "War Mop" (1983) from the Lebanon Series, we see a mechanized mop hitting a TV monitor. The video shows "news footage

of the skeletal remains of the Lebanese town Damour, panning to a Palestinian woman in the wreckage of her home. (...) The political information that's coming to me – which anyone else might have access to – physicalizes itself as dreams, hallucinations, sensations of being in a place I have never seen literally or actually been. With the increasing bombardments of Lebanon after the Israeli invasion in 1982, I began to see imagery - on the threshold of sleeping - of very specific buildings blowing up, being bombed: an old stone library blasted by rocket fire and imploding. I pursue these chimera back into the world where they are located, to deepen the world might be." (Carolee Schneemann)

Group Show

7 May - 31 July, 2011

Evelyne Axell, Maria Bartuszova, Louise Bourgeois, Audrey Capel Doray, Ruth Francken, Carolee Schneemann, Penny Slinger, Marjorie Strider, Toyen

This show presents work of women artists which - by no means - can be simply grouped under one category, - and surely the notion of surrealism has still a mildly painful association to some as it was a style which even at its dawn in modernism was never fully accepted among the progressive avant-gardes.

Surrealism is often regarded for holding an alliance with kitsch and the sentimental, its suspect to introversion, and of building on non-progressive definitive forms and exaggerated naturalistic images. Thus, the politics of Surrealism were often obscured, even as its forms border on the confrontational language of Dada and the protagonists of the pre- and postwar movement were often politically active, e.g. as members of Communist organizations or as anarchists.

In the spectrum of its ambivalent reception surrealism could also be regarded as an inherently effeminate art form. It definitely offered a particular potential of radical articulation for women artists throughout.

The immediacy and efficiency of surrealist language, the often blunt and daring eroticism, the realism of 'objet trouvé', and its precise expressions of maximum evocative strengths, provide a genuine terrain for women artists' (proto)-feminist - and in a wider perspective politically engaged language.

This show further juxtaposes works by Eastern European artists next to the work of Western European and American artists from the same mostly post-war period. We see works of lesser known, or to date almost entirely overlooked artists next to works, which are more prominent to the US public's memory. Despite the political divisions of the iron curtain and the Cold War, we see astonishing familiarities in expression and themes, as well as interesting distinctions. The radical internationalism of the pre-war avant-garde made it easy to espouse a non- national movement such as surrealism. After the war, surrealism continued to appear in new updated forms, yet at times socially and geographically disconnected. Surrealist language lived on in numerous forms and ways, often leading to new art movements such as Fluxus and Pop Art or fusing with radically contemporary forms.

In a focus show we present 11 works of Polish photographer Zofia Rydet whose work has not been shown for a long time and was recently rediscovered by the Warsaw based gallery Asymetria. Rydet created a fascinating series of photomontages titled "The World of Feelings and Imagination" from the 1960s-70s advancing surreal and Dadaist motifs, while she also worked in photo reportage inspired by the meta-national show "The Family of Man" which came to Warsaw in 1955.

Rydet's motifs such as the "Mannequins" and "Threat" have an obscure take on the post-war period in images where a soldier in a uniform more reminiscent of World War I (and therefore enhancing the stylistic reference to Dada) makes his appearance in abandoned alleys and ruins, his body de-collaged into a crippled ghostlike pose.

In other photomontages we see stripped mannequins gathering in desolate post- apocalyptic landscapes possibly hinting to the threat of nuclear destruction in the Cold War time. In other motifs Rydet invented a peculiar travesty by applying 'masks' of a woman and a man with eerily deformed faces to the bodies of female and male protagonists positioned in oppressive domestic milieus and in nostalgic rural scenes, which seem to be taken from Rydet's reportage work. In some cases the stone-faced introvert female mask is attached to a male body creating a subtext of androgyny in social milieus, which seems too geographically remote and anachronistic for such manipulations of gender masquerade. These works have a truly unfamiliar atmosphere where sensations of tenderness, violence and alienation are kept in an impenetrable balance.

Rydet's work owns "a certain kind of understatement, an unexpected transition of vision. Inspired by that naïve iconography and simple minded narration, by primitive religiousness and atmosphere of folk adages and the memory of war – we enter the world of her own surreality." (Ursula Czartoryska)

Belgian artist Evelyne Axell was tutored by Surrealist and friend René Magritte and developed her own contemporary style of Pop-Surrealism. Her early work "The Erotic Machine or Concept of Boy Art"("Mec Art"), 1964, was painted programmatically 'in the style of Magritte' and mocks the Duchampian idea of the erotic machine.

In "Cercle Vicieux (Rouge)" from 1968 Axell further responds to Duchamp's concept of the isolated gender zones and the self-indulged activities of the bride and bachelors in his seminal work, the "Large Glass": in her imposing circular relief painting we see a monolithic female torso of walking legs occupying the pictorial realm, the figure being encapsulated in a red 'vicious circle', self-contained and undefined in its direction.

Marjorie Strider moved from Pop Art's joyful painterly optimism to intrusive assemblage work with colored foam as in the site-specific installation "Stair Pour" (976) at the University Graduate Center, New York. Strider worked with the foam material in ample ways from sculptural assemblage to relief paintings and drawings.

The most political variation of the foam series appears in the gouache drawing "Lady Liberty" (1972), where blue foam is pouring out of the crown of the Statue of Liberty, a still pre-trauma 1970s Pop vision of national 'threat'.

Canadian artist Audrey Capel Doray revisited the Dadaist 'Automaton' in a new Pop-language in her signature piece of the "Armored Lady"(1968). There is a sound piece of experimental jazz integrated into the iconic piece composed by Mark Oliver and the artist herself. The bust lights up in a fast rhythm exposing a text collage with notions such as "True", "East" and "West".

Around the same time British artist Penny Slinger (who today lives in California) created resin sculptures of body casts such as "Golden Triangle" (1976) and the eerie dark earlier sculpture "Bride in the Bath" (1969), a real bath tub in which a life size female figure lies covered in a full body black veil.

Parallel to Louise Bourgeois' abstracted phallic forms such as "Untitled (Sleep II)" and Alina Szapoznikow's body casts and semi-abstract corporeal landscapes, Czech sculptor Maria Bartuszova developed sculptures of "bionical" abstraction. While her style is more minimal and less corporeal it is nonetheless fetishistic. Although Bartuszova was one of the widely talked about rediscoveries of the last Documenta XII, her groundbreaking work remained to date relatively unknown in the US.

Like the Polish Alina Szapocznikow in the late 1960s and early 70s, the Prague- born, later American and French resident Ruth Francken, kept her outstanding style and important aesthetic distance to the ruling Parisian movement of "Nouveau Realism". Apart from her design classic of the "Homme, Chaise" (1970) (for which she took a full body cast of a young man, as Szapocznikow did from the body of her son Piotr in 1971), her work is hardly known anymore, although she (as well as her Polish contemporary) received an early solo exhibition in the Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (both under curator Suzanne Page). She was prominently associated and courted by the Parisian nobility of intellectuals. Her work presented a genuine fusion of exaggerated Pop sensibility in black & white and feminist surreal interventionism such as in the object "Televenus" (1969) and the photo-relief "Lilith" (1970).

There is a deep involvement and far reach of political expression in the work of particularly women artists of the classic period of Surrealism and Dadaism, and one finds an extraordinary richness of expression in women artists' works in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, revisiting surrealist and Dadaist styles, techniques and tropes for their contemporary aesthetic, political intentions and urgencies.

During the war in 1944 first generation Surrealist Toyen created a series of etchings titled "Cache-toi guerre!" ("Collapse war!"). The experience of the war appears in the manner of this "intensified truth" which we later find in the photomontages of Zofia Rydet and in the work of Carolee Schneemann. The style, which draws directly on current political atrocities finds at the same time a language transcending the political into a more general insight in its makings and inner operations.

The familiarities in techniques and even themes of these photomontages with Schneemann's "Illinois Central" (1968) for example and Penny Slinger's collages from the series "An Exorcism" (1977) are striking. In "Illinois Central" we see an epic panorama of rural American landscape over which a female nude in archaic rags is floating like a death angel associating once more the nuclear destruction or the images of Napal bombing in the Vietnam. In her performance "Snows", 1967, Schneemann developed a complex "Kinetic Theater" about her outrage about the Vietnam atrocities.

In Schneemann's kinetic video installation "War Mop" (1983) from the Lebanon Series, we see a mechanized mop hitting a TV monitor. The video shows "news footage

of the skeletal remains of the Lebanese town Damour, panning to a Palestinian woman in the wreckage of her home. (...) The political information that's coming to me – which anyone else might have access to – physicalizes itself as dreams, hallucinations, sensations of being in a place I have never seen literally or actually been. With the increasing bombardments of Lebanon after the Israeli invasion in 1982, I began to see imagery - on the threshold of sleeping - of very specific buildings blowing up, being bombed: an old stone library blasted by rocket fire and imploding. I pursue these chimera back into the world where they are located, to deepen the world might be." (Carolee Schneemann)