Raymond Pettibon

13 Jun - 31 Jul 2014

RAYMOND PETTIBON

13 June - 31 July, 2014

Contemporary Fine Arts is pleased to present new works by Raymond Pettibon (born in 1957).

Things are as bad between image and text, “free art” and “scholarly prose” as the cliché

of the erotic muse and the professor with the magnifying glass suggests. If not worse because it is well known that reality is often more inventive than the imagination. Therefore, it seems advisable to avoid this danger area. However, the cumulation of gaffes and “accidents” indicates a productive source, and this is probably why Raymond Pettibon spends time there, because whatever may have been said about his art so far: he does not just mingle drawing and language, or animate icons and slogans with the panache of his writing. Rather, he is a specialist for nuances, a master of the puzzling, a virtuoso of the remark that does not quite fit.

His pictures come about where he can motivate figures and signs that populate official and private thinking to take another ride, and he takes them in every facet of their intentions. Whether reactionary or conservative, committed or neo-puritan, correct or feminist, mercantile or intimate, religious or academic, active or intellectual, even if they are just imagined or speak quite involuntarily. In the first years of his activity publishing things, he wanted to equip the audience – and that was around 1980 largely the no illusions generation of punk rock – with an inkling that the radicalness in his “views” was not quite as smug as theirs. By now, however, his products cross the field of art, and there the skin is a little thicker, filled with sensibility and other valuables. In return, he abandoned the protection of ironic distance.

Raymond Pettibon was born in 1957 in Hermosa Beach, Los Angeles, not far from one of the beautiful beaches where the Pacific Ocean throws its flotsam back to the Land of Opportunities. And still, every day, the sun shines on the enjoyment of leisure time, be that as pleasure in the waves of the ocean, of fashion, music, or film. Raymond Pettibon has moved in all these media. He was a surfer who drew a line in the morning on the latest “new wave” that at its peak went down completely unmoved. During the day, he seemed to guarantee the art work of a music label, and in the evening, he was the man with the camera who strode the ideals of the underground; there, he portrayed the armed struggle of the weathermen in underpants or the daughter of a powerful media baron, converted from a kidnapping victim to a soldier of the Symbionese Liberation Army. That he recently moved to Manhattan and now looks over the canyons of the city from the 38th floor might make sense in theory because it would mean that he arrived at the centre of the market that has given his pictures a remarkable popularity in recent years. The music world denied that to him while at the same time using all his contributions without taking a closer look or doing any research. The art world loves above all his surfers, in blue on paper; but he stays away from the rituals of the art market.

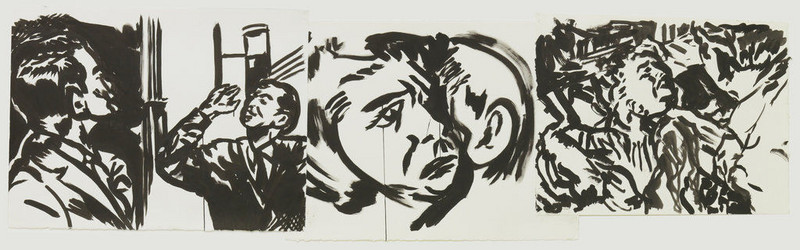

Raymond Pettibon’s drawings take their point of departure in the blatant confidence of a propaganda product. On the outside, they are supposed to be so simple and seductive, convincing and plausible, that they settle in people’s minds as their own ideas. He also values this mixture of stereotype and confusion, placing catchy phrases next to well-known motifs. He pulls his figures in black ink from the stream of images and gives them phrases that read as a fluid thought of their problems, a language that flows easily in the slope of a melody, familiar and possibly actually borrowed from a piece of much read literature. And usually right next to this, the next words land on the paper, in another voice, with new thoughts and notions, and slowly a tension arises in this entire ensemble of splotches, contrasts, and reflected lights. Constellations that just a moment ago were framed by a stable scene now drift apart. The lines of the writing are interrupted, and loose brushstrokes – in the players like the disorder of a drunken speech – uncouple the rest. In the end, the beginning has also lost its unambiguousness, and every line, be it in the course of a gesture, in the flutter of a face, or the jumpy lines of his letters, has slipped away from its purpose.

In Raymond Pettibon’s drawings, the inconsistencies are always a little more obvious than a technocrat of propaganda would like. Sometimes he uses the small differences that upset the balance between image and text as an entry into the unsuitable. But that would not be sufficient because he places his figures quite consciously above fault lines. Once the first gap is placed, like a director on remote control, he pushes it apart with further gaps, teases mistake after mistake from them, a process where foreground and sustainability must “yield” in both directions, in the direction of incredibility and coherent simplicity. Hence the familiar getup of his actors: man with weapon, nude woman, hippie with knife, tough gangster. Inside their recognition value, they mean business without much ado, only to cross the border of simple interpretation in the next step. Punks are suddenly dreamy and gay, women become merciless judges and victims of their own agency, gunmen turn into mother’s boys and start to ponder things – an exposure that Pettibon pursues with an exaggeration that is too obvious because he knows: even the desire for a distance that wants to have seen through the kitsch in the end adheres to the despised cliché.

Those who wish to establish Raymond Pettibon’s pictorial world within the frame of a political morality that today believes the good is on its side, and thus fit it into the accordingly renovated categories, can merely try to “exonerate” themselves. Of course we might explain that with him, the clichés – the tough guys and naked ladies – are somewhat more complex, that the “false images” on his stage are always taken in by his own convictions. But such an approach will inevitably miss the foundation, his political atheism. And at any rate, his drawings contain instructions for the proper orientation in the current consensus: as one of the many errors in which the characters of his stories encounter one another.

(Text: Roberto Ohrt; Translation: Wilhelm v. Werthern)

13 June - 31 July, 2014

Contemporary Fine Arts is pleased to present new works by Raymond Pettibon (born in 1957).

Things are as bad between image and text, “free art” and “scholarly prose” as the cliché

of the erotic muse and the professor with the magnifying glass suggests. If not worse because it is well known that reality is often more inventive than the imagination. Therefore, it seems advisable to avoid this danger area. However, the cumulation of gaffes and “accidents” indicates a productive source, and this is probably why Raymond Pettibon spends time there, because whatever may have been said about his art so far: he does not just mingle drawing and language, or animate icons and slogans with the panache of his writing. Rather, he is a specialist for nuances, a master of the puzzling, a virtuoso of the remark that does not quite fit.

His pictures come about where he can motivate figures and signs that populate official and private thinking to take another ride, and he takes them in every facet of their intentions. Whether reactionary or conservative, committed or neo-puritan, correct or feminist, mercantile or intimate, religious or academic, active or intellectual, even if they are just imagined or speak quite involuntarily. In the first years of his activity publishing things, he wanted to equip the audience – and that was around 1980 largely the no illusions generation of punk rock – with an inkling that the radicalness in his “views” was not quite as smug as theirs. By now, however, his products cross the field of art, and there the skin is a little thicker, filled with sensibility and other valuables. In return, he abandoned the protection of ironic distance.

Raymond Pettibon was born in 1957 in Hermosa Beach, Los Angeles, not far from one of the beautiful beaches where the Pacific Ocean throws its flotsam back to the Land of Opportunities. And still, every day, the sun shines on the enjoyment of leisure time, be that as pleasure in the waves of the ocean, of fashion, music, or film. Raymond Pettibon has moved in all these media. He was a surfer who drew a line in the morning on the latest “new wave” that at its peak went down completely unmoved. During the day, he seemed to guarantee the art work of a music label, and in the evening, he was the man with the camera who strode the ideals of the underground; there, he portrayed the armed struggle of the weathermen in underpants or the daughter of a powerful media baron, converted from a kidnapping victim to a soldier of the Symbionese Liberation Army. That he recently moved to Manhattan and now looks over the canyons of the city from the 38th floor might make sense in theory because it would mean that he arrived at the centre of the market that has given his pictures a remarkable popularity in recent years. The music world denied that to him while at the same time using all his contributions without taking a closer look or doing any research. The art world loves above all his surfers, in blue on paper; but he stays away from the rituals of the art market.

Raymond Pettibon’s drawings take their point of departure in the blatant confidence of a propaganda product. On the outside, they are supposed to be so simple and seductive, convincing and plausible, that they settle in people’s minds as their own ideas. He also values this mixture of stereotype and confusion, placing catchy phrases next to well-known motifs. He pulls his figures in black ink from the stream of images and gives them phrases that read as a fluid thought of their problems, a language that flows easily in the slope of a melody, familiar and possibly actually borrowed from a piece of much read literature. And usually right next to this, the next words land on the paper, in another voice, with new thoughts and notions, and slowly a tension arises in this entire ensemble of splotches, contrasts, and reflected lights. Constellations that just a moment ago were framed by a stable scene now drift apart. The lines of the writing are interrupted, and loose brushstrokes – in the players like the disorder of a drunken speech – uncouple the rest. In the end, the beginning has also lost its unambiguousness, and every line, be it in the course of a gesture, in the flutter of a face, or the jumpy lines of his letters, has slipped away from its purpose.

In Raymond Pettibon’s drawings, the inconsistencies are always a little more obvious than a technocrat of propaganda would like. Sometimes he uses the small differences that upset the balance between image and text as an entry into the unsuitable. But that would not be sufficient because he places his figures quite consciously above fault lines. Once the first gap is placed, like a director on remote control, he pushes it apart with further gaps, teases mistake after mistake from them, a process where foreground and sustainability must “yield” in both directions, in the direction of incredibility and coherent simplicity. Hence the familiar getup of his actors: man with weapon, nude woman, hippie with knife, tough gangster. Inside their recognition value, they mean business without much ado, only to cross the border of simple interpretation in the next step. Punks are suddenly dreamy and gay, women become merciless judges and victims of their own agency, gunmen turn into mother’s boys and start to ponder things – an exposure that Pettibon pursues with an exaggeration that is too obvious because he knows: even the desire for a distance that wants to have seen through the kitsch in the end adheres to the despised cliché.

Those who wish to establish Raymond Pettibon’s pictorial world within the frame of a political morality that today believes the good is on its side, and thus fit it into the accordingly renovated categories, can merely try to “exonerate” themselves. Of course we might explain that with him, the clichés – the tough guys and naked ladies – are somewhat more complex, that the “false images” on his stage are always taken in by his own convictions. But such an approach will inevitably miss the foundation, his political atheism. And at any rate, his drawings contain instructions for the proper orientation in the current consensus: as one of the many errors in which the characters of his stories encounter one another.

(Text: Roberto Ohrt; Translation: Wilhelm v. Werthern)