Aribert von Ostrowski

14 Mar - 18 Apr 2015

© Aribert von Ostrowski

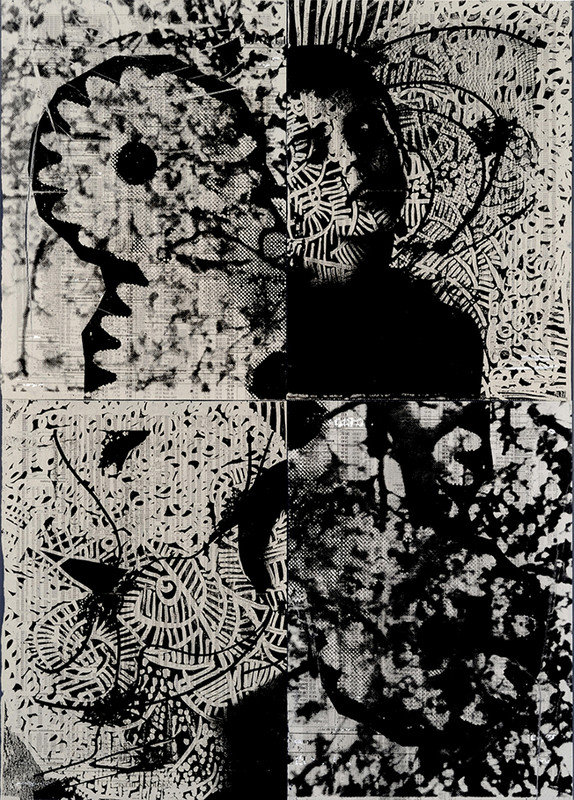

The Romantic Size of Capitalism (Untitled) # 19, 2015, xerox, correction pen, newspaper, acrylic, canvas

100 x 72 x 2 cm

The Romantic Size of Capitalism (Untitled) # 19, 2015, xerox, correction pen, newspaper, acrylic, canvas

100 x 72 x 2 cm

ARIBERT VON OSTROWSKI

The Romantic Size of Capitalism

14 March – 18 April 2015

Over half a century ago, Gerhard Richter, Konrad Lueg, Sigmar Polke and Manfred Kuttner began their project of confronting those living during the economic miracle in Germany, the so called Wirtschaftswunder, with an art movement called capitalist realism. This term conjoins irony, critique and the wish for reform in itself – functioning as an analogy to socialist realism, it was meant to bring movement to the world of Western German consumption via the rhythms of pop.

By way of performances that would today be labelled as guerilla art by the media posse, students movements began to form. Konrad Lueg became Konrad Fischer and his eponymous gallery curated not only his artist friends but also Carl Andre, Bruce Naumann or On Kawara. Today, these artists count among the most influential in contemporary art; their retrospectives fill the big institutions (currently: Polke in the Museum Ludwig or Kawara in the Guggenheim), and their prizes globally dominate the statistics put forth by auction houses. These oeuvres thus established the movement of capitalist realism which seems to manifest itself through sales, admission fees, insurance sums and visitor numbers alone. Not to speak of the critical potential inherent to the works themselves.

In his exhibition The Romantic Size of Capitalism, Aribert von Ostrowski creates a new stylistic approach: capitalist romanticism. For a few years now, the ground coat applied to his works has been consisting of numerical tables showing current stock exchange values as to be found in the large German-speaking newspapers every day.

In the past, these works either stood on their own without additional commentary, embedded into the typical newspaper print grids, or they were layered and blackened with comic-like Cheshire cat faces evoking Polke and other materials. The leaden empty waste lands of numbers and calculations jerkily and mechanically judder in front of the viewer‘s eye, jumbling analogue and mysterious market values.

In The Romantic Size of Capitalism however, Ostrowski now spills love over his paper – his works not only turn more colourful, but whole rainbows spread over the canvasses. Here and there, it is even possible to prescribe painterly characteristics. These interventions shout pop propaganda: in grand gestures, capitalism is infused with the the radiance of colour, newspaper pages turn into vibrantly hued jazz.

Cold cash is made warmer, abstract values come to life and the black printing ink transforms into gold bars? It is that easy – and the (art) market functions in a similarly simple way. In his exhibition, Ostrowski lays bare both the art discourse and the fragile bubble of stock market speculation. The “romantic dimension of capitalism” after all broaches the issue of art as commodity – and the inherent power of these structures.

In times of statistical surveys and measuring artistic objects according to their potential venture, we have become quick to ascribe certain value, to determine which canvas sizes are easier to sell, which colours are being preferred by potential buyers, and which ideal age an artist should have to be able to make a head start in the marketplace.

This robs art of its dark powers. What is left is the romantic dimension of a kind of capitalism suited for comfortably hanging on living room walls; a capitalism that follows the same beaten paths as described and performed in the financial sections of newspapers.

A contemporary capitalist realism, however, can be found on the streets of Athens, in the production halls of Shenzen. Aribert von Ostrowski displays modern art as romantically glorified commodity belonging to a world that is fixated on profit accumulation. That we can still recognise this critique while being basked in these canvasses‘ audacious radiance, speaks of their high quality.

Konstantin Lannert

via Reflektor M

translated Jennifer Leetsch

The Romantic Size of Capitalism

14 March – 18 April 2015

Over half a century ago, Gerhard Richter, Konrad Lueg, Sigmar Polke and Manfred Kuttner began their project of confronting those living during the economic miracle in Germany, the so called Wirtschaftswunder, with an art movement called capitalist realism. This term conjoins irony, critique and the wish for reform in itself – functioning as an analogy to socialist realism, it was meant to bring movement to the world of Western German consumption via the rhythms of pop.

By way of performances that would today be labelled as guerilla art by the media posse, students movements began to form. Konrad Lueg became Konrad Fischer and his eponymous gallery curated not only his artist friends but also Carl Andre, Bruce Naumann or On Kawara. Today, these artists count among the most influential in contemporary art; their retrospectives fill the big institutions (currently: Polke in the Museum Ludwig or Kawara in the Guggenheim), and their prizes globally dominate the statistics put forth by auction houses. These oeuvres thus established the movement of capitalist realism which seems to manifest itself through sales, admission fees, insurance sums and visitor numbers alone. Not to speak of the critical potential inherent to the works themselves.

In his exhibition The Romantic Size of Capitalism, Aribert von Ostrowski creates a new stylistic approach: capitalist romanticism. For a few years now, the ground coat applied to his works has been consisting of numerical tables showing current stock exchange values as to be found in the large German-speaking newspapers every day.

In the past, these works either stood on their own without additional commentary, embedded into the typical newspaper print grids, or they were layered and blackened with comic-like Cheshire cat faces evoking Polke and other materials. The leaden empty waste lands of numbers and calculations jerkily and mechanically judder in front of the viewer‘s eye, jumbling analogue and mysterious market values.

In The Romantic Size of Capitalism however, Ostrowski now spills love over his paper – his works not only turn more colourful, but whole rainbows spread over the canvasses. Here and there, it is even possible to prescribe painterly characteristics. These interventions shout pop propaganda: in grand gestures, capitalism is infused with the the radiance of colour, newspaper pages turn into vibrantly hued jazz.

Cold cash is made warmer, abstract values come to life and the black printing ink transforms into gold bars? It is that easy – and the (art) market functions in a similarly simple way. In his exhibition, Ostrowski lays bare both the art discourse and the fragile bubble of stock market speculation. The “romantic dimension of capitalism” after all broaches the issue of art as commodity – and the inherent power of these structures.

In times of statistical surveys and measuring artistic objects according to their potential venture, we have become quick to ascribe certain value, to determine which canvas sizes are easier to sell, which colours are being preferred by potential buyers, and which ideal age an artist should have to be able to make a head start in the marketplace.

This robs art of its dark powers. What is left is the romantic dimension of a kind of capitalism suited for comfortably hanging on living room walls; a capitalism that follows the same beaten paths as described and performed in the financial sections of newspapers.

A contemporary capitalist realism, however, can be found on the streets of Athens, in the production halls of Shenzen. Aribert von Ostrowski displays modern art as romantically glorified commodity belonging to a world that is fixated on profit accumulation. That we can still recognise this critique while being basked in these canvasses‘ audacious radiance, speaks of their high quality.

Konstantin Lannert

via Reflektor M

translated Jennifer Leetsch