Elisabetta Benassi

07 May - 17 Sep 2017

ELISABETTA BENASSI

It starts with the firing

7 May – 17 September 2017

It starts with the firing is the new site-specific project by Elisabetta Benassi for Collezione Maramotti.

The starting point of the exhibition is the controversy triggered by American artist Carl Andre’s 1966 work titled Equivalent VIII, which is composed of 120 bricks placed on two overlapping rows to form a rectangular shape. The work was purchased by London’s Tate Gallery in 1972 for several thousand pounds. At the time, the British press attacked the purchase by ridiculing the museum’s choice with articles and vignettes.

Elisabetta Benassi has referred back to the traces of these press materials, now held in the Tate Archives (curiously, put together by Carl Andre himself and donated to the museum), to open up and activate the controversy by extrapolating excerpts from the original newspaper cuttings, assembled in an artist’s book and turned into billboards positioned around the town of Reggio Emilia.

The exhibition starts outside the town: five sentences are printed on billboards located in the outskirts and on buses driving through the historical centre of Reggio Emilia. They are in English and talk about bricks: Upon these bricks; Bricks a hot favourite; The bricks pull the crowds; This Bricks could build a bad reputation; A brick is a brick is a brick...; My wall is going cheap; Gallery bricks silence; Money crisis and the art Bricks; Man behind the bricks; The bricks are useful; Art may come and art may go but a brick is a brick for Ever. Bricks are for homes!

What do these words refer to? Is it an advertising campaign? Are these political slogans? What is the relationship between art and bricks?

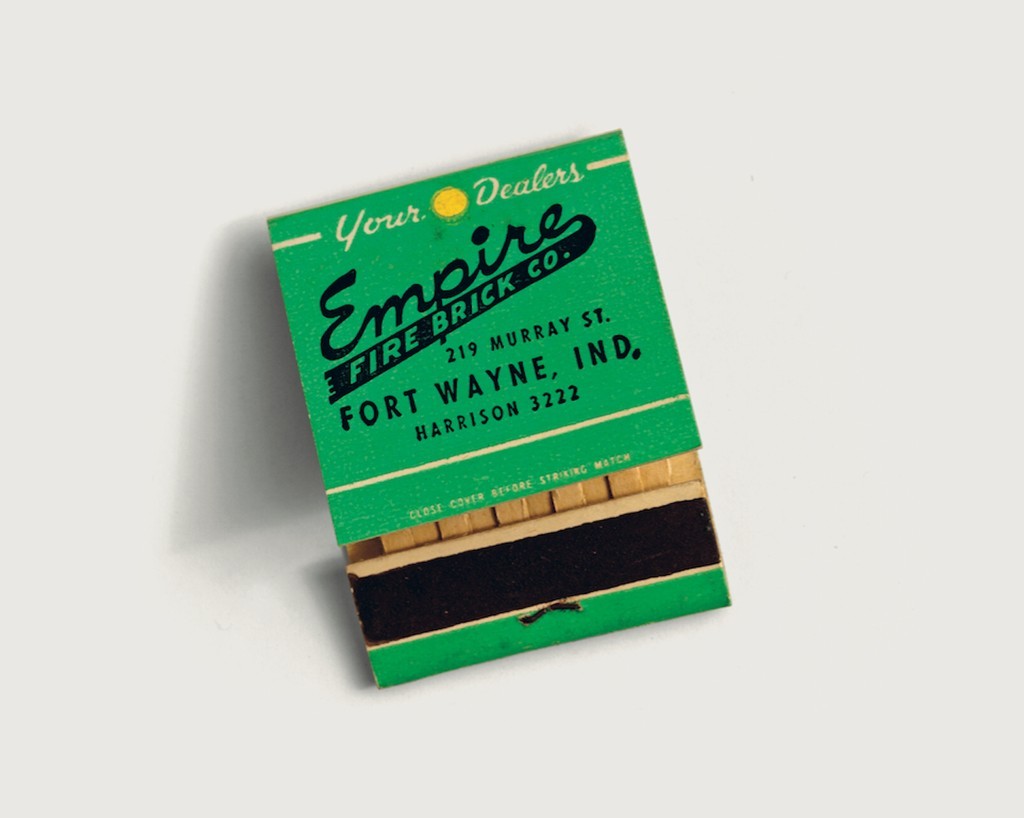

From outside to inside, from the town to Collezione Maramotti, the posters lead us toward the exhibition space, where the works by Elisabetta Benassi create a relationship between “objects” belonging to the history of the location –the first Max Mara factory, now housing the Collection– and other elements linked to a much wider story, not solely Italian, by creating “stopovers” in an itinerary that can be assembled at will by viewers. Every room presents a single work that seems to have survived the disappearance of the context that originally housed it. Some “objects“ are presented with their “names”: Prosperity, Empire (which recalls another work by Andre) are brands, but also act as metaphors, oracles ironically asking questions; they seem to us both familiar and out of place. An industrial steam presser, carpets wedged into a brick wall, a slanted pillar proudly exhibiting its trademark: these devices ironically summarise the contradictions of history, its slippages and, at times, the total collapse of the meanings it had imposed on names and things. But the instability, the enigmas that these works propose do not have anything vague or evocative. Instead, they address something that sounds all too familiar: the loss of trust in the promises of technique, the posthumous world emerging after the failure of ideologies and their supposed remedies; the surrendering of forces squandering memories and communities and making them feral again.

What could the controversy about Carl Andre’s work purchased by Tate teach us? Perhaps our certainties on the increased farsightedness and sensitivity of our time are essentially illusions, that the “bricks” of our society –the“values” on which it is based– are always precarious, and its structures are always on the brink of collapsing, yet are also capable of transforming themselves –when in the artist’s hands– from somewhat-constrained elements into pieces of a multifaceted mosaic.

It starts with the firing

7 May – 17 September 2017

It starts with the firing is the new site-specific project by Elisabetta Benassi for Collezione Maramotti.

The starting point of the exhibition is the controversy triggered by American artist Carl Andre’s 1966 work titled Equivalent VIII, which is composed of 120 bricks placed on two overlapping rows to form a rectangular shape. The work was purchased by London’s Tate Gallery in 1972 for several thousand pounds. At the time, the British press attacked the purchase by ridiculing the museum’s choice with articles and vignettes.

Elisabetta Benassi has referred back to the traces of these press materials, now held in the Tate Archives (curiously, put together by Carl Andre himself and donated to the museum), to open up and activate the controversy by extrapolating excerpts from the original newspaper cuttings, assembled in an artist’s book and turned into billboards positioned around the town of Reggio Emilia.

The exhibition starts outside the town: five sentences are printed on billboards located in the outskirts and on buses driving through the historical centre of Reggio Emilia. They are in English and talk about bricks: Upon these bricks; Bricks a hot favourite; The bricks pull the crowds; This Bricks could build a bad reputation; A brick is a brick is a brick...; My wall is going cheap; Gallery bricks silence; Money crisis and the art Bricks; Man behind the bricks; The bricks are useful; Art may come and art may go but a brick is a brick for Ever. Bricks are for homes!

What do these words refer to? Is it an advertising campaign? Are these political slogans? What is the relationship between art and bricks?

From outside to inside, from the town to Collezione Maramotti, the posters lead us toward the exhibition space, where the works by Elisabetta Benassi create a relationship between “objects” belonging to the history of the location –the first Max Mara factory, now housing the Collection– and other elements linked to a much wider story, not solely Italian, by creating “stopovers” in an itinerary that can be assembled at will by viewers. Every room presents a single work that seems to have survived the disappearance of the context that originally housed it. Some “objects“ are presented with their “names”: Prosperity, Empire (which recalls another work by Andre) are brands, but also act as metaphors, oracles ironically asking questions; they seem to us both familiar and out of place. An industrial steam presser, carpets wedged into a brick wall, a slanted pillar proudly exhibiting its trademark: these devices ironically summarise the contradictions of history, its slippages and, at times, the total collapse of the meanings it had imposed on names and things. But the instability, the enigmas that these works propose do not have anything vague or evocative. Instead, they address something that sounds all too familiar: the loss of trust in the promises of technique, the posthumous world emerging after the failure of ideologies and their supposed remedies; the surrendering of forces squandering memories and communities and making them feral again.

What could the controversy about Carl Andre’s work purchased by Tate teach us? Perhaps our certainties on the increased farsightedness and sensitivity of our time are essentially illusions, that the “bricks” of our society –the“values” on which it is based– are always precarious, and its structures are always on the brink of collapsing, yet are also capable of transforming themselves –when in the artist’s hands– from somewhat-constrained elements into pieces of a multifaceted mosaic.