Abbas Akhavan

curtain call

23 Jun - 26 Nov 2023

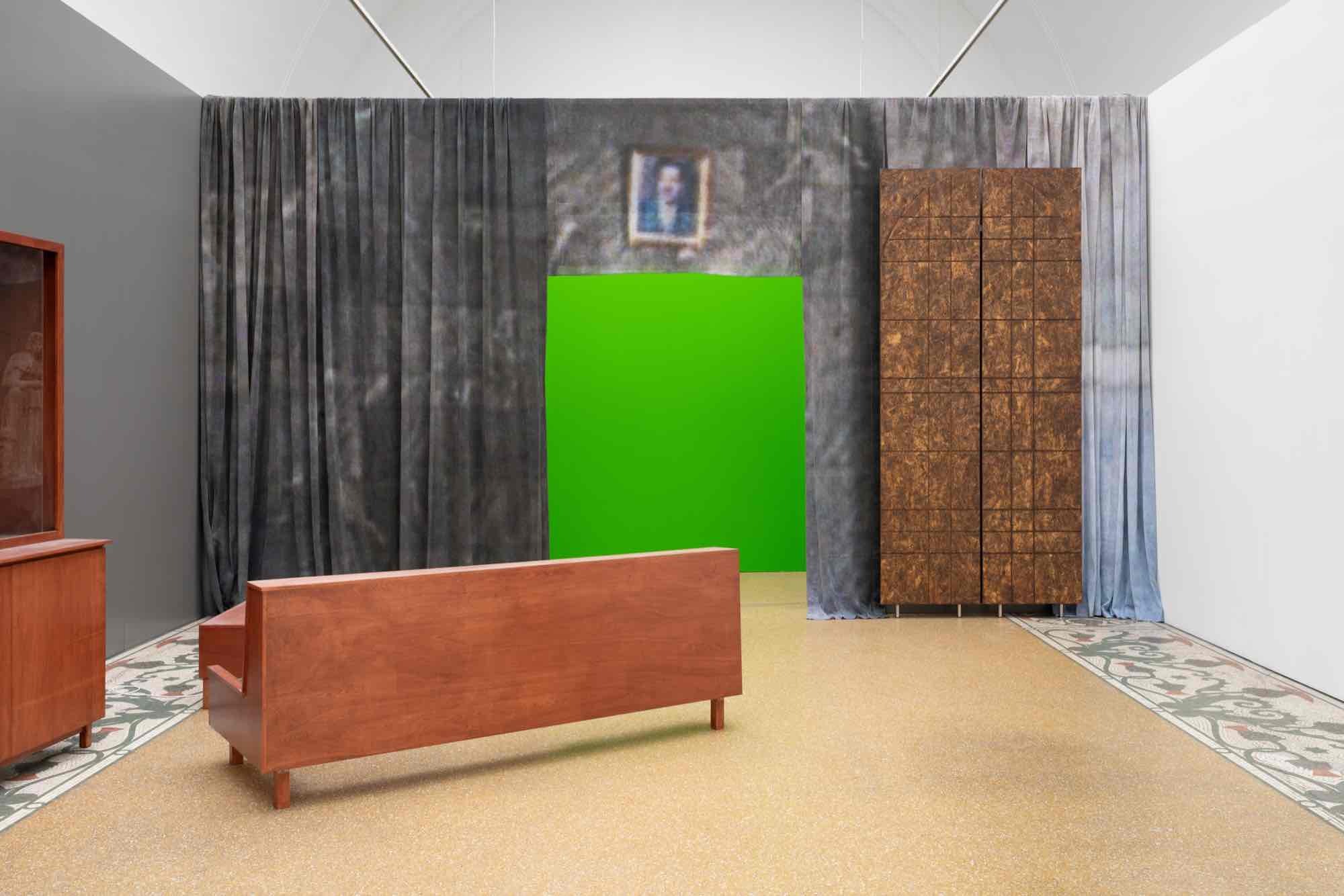

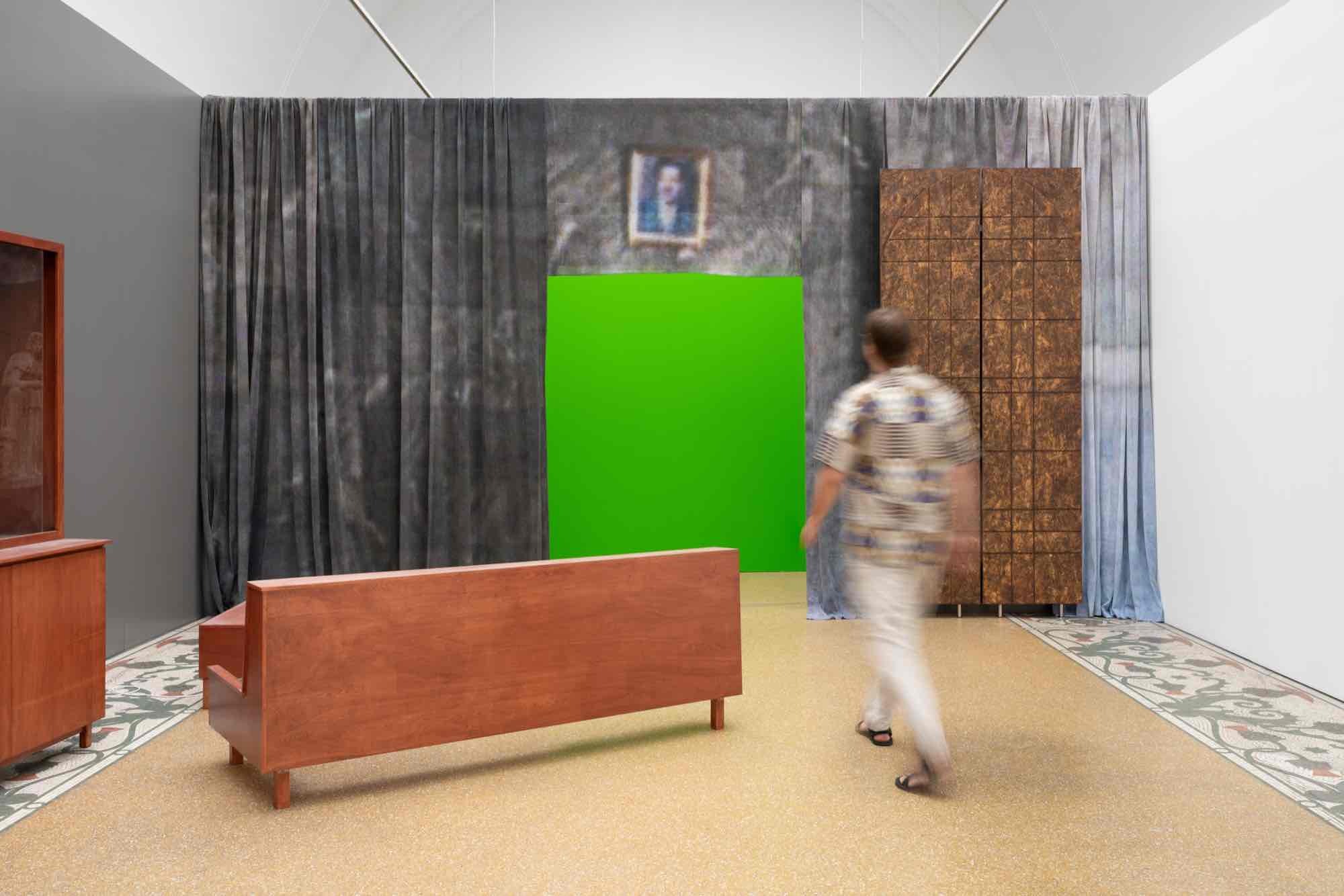

Abbas Akhavan, curtain call, variations on a folly (2021–) Installation view at Copenhagen Contemporary (2023) Photo: David Stjernholm

Abbas Akhavan, curtain call, variations on a folly (2021–) Installation view at Copenhagen Contemporary (2023) Photo: David Stjernholm

Abbas Akhavan, curtain call, variations on a folly (2021–) Installation view at Copenhagen Contemporary (2023) Photo: David Stjernholm

Abbas Akhavan, curtain call, variations on a folly (2021–) Installation view at Copenhagen Contemporary (2023) Photo: David Stjernholm

Abbas Akhavan, curtain call, variations on a folly (2021–) Installation view at Copenhagen Contemporary (2023) Photo: David Stjernholm

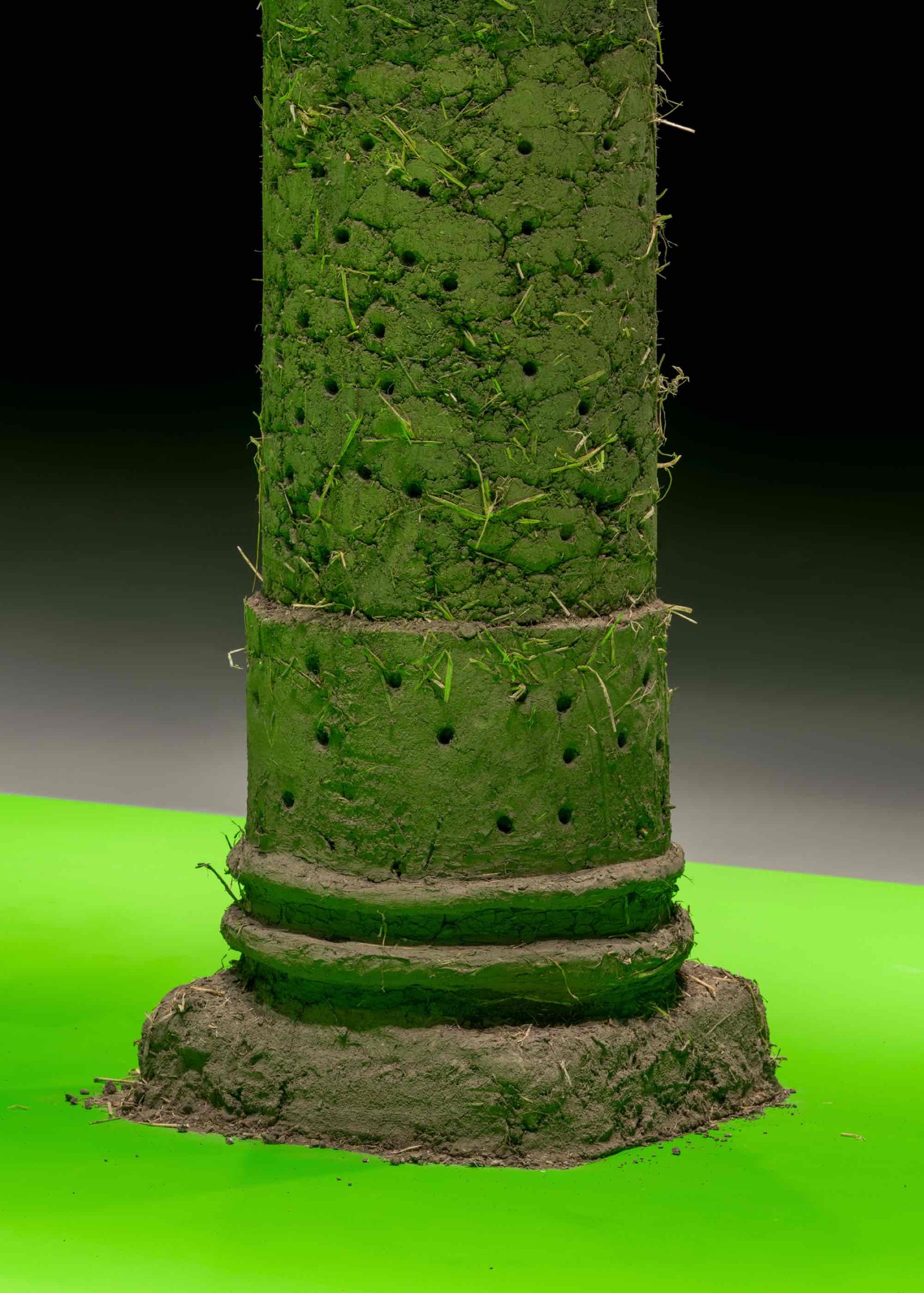

Abbas Akhavan, curtain call, cast for a folly (2019–) Installation view at Glyptoteket (2023)

Photo: David Stjernholm

Photo: David Stjernholm

Abbas Akhavan, curtain call, cast for a folly (2019–) Installation view at Glyptoteket (2023)

Photo: David Stjernholm

Photo: David Stjernholm

Abbas Akhavan, curtain call, cast for a folly (2019–) Installation view at Glyptoteket (2023)

Photo: David Stjernholm

Photo: David Stjernholm

Abbas Akhavan, curtain call, cast for a folly (2019–) Installation view at Glyptoteket (2023)

Photo: David Stjernholm

Photo: David Stjernholm

The world is full of untold and silenced stories transmitted for generations by people and artefacts migrating across time, borders and historical events. How should their stories be told and who has the right to tell them? In a new threeyear exhibition collaboration, CC and the Glyptotek will shed light on some of the questions that arise in a global world where people and cultural heritage are constantly on the move.

The joint exhibition programme, Hosting Histories: Revisiting Cultural Heritage of the Middle East and Beyond, gives three international contemporary artists, either residing in the Middle Eastern region or belonging to Middle Eastern diasporas, access to the Glyptotek’s ancient collections and the opportunity to develop a solo exhibition across both institutions. Together with CC and the Glyptotek, the artists will revisit some of history’s silenced and untold stories and – through their own works – bring forward new perspectives on how these stories can be voiced today.

Ghostly revival of lost heritage

The first exhibition in the series is titled curtain call and created by the Montreal-based artist Abbas Akhavan (b. 1977, Tehran). In his first solo exhibition in the Nordic region, Akhavan presents two of his largest installations on view together for the first time: cast for a folly (2019–) and variations on a folly (2021– ). With rustic columns, vibrating green screens and dusty, theatre props, Akhavan re-stages existing architectural sites and historical events displaced in time and place and unsettling in their message.

At the Glyptotek, the installation cast for a folly is shown exactly 20 years after the US invaded Iraq with allied countries including Denmark. The installation is a theatrical staging of a photograph of the lobby of the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad, taken shortly after it was looted during the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The furniture is constructed in fragments and the Assyrian lion sculpture in heavy basalt has been resurrected out of cob, an ancient building material made from sand, clay, water and straw. A kicked-in door has become a green screen, while water lilies float in a plastic container. Now occupying a different time and space, the re-staging of the looted museum asks: Who inherits the ruins of war?

On display at CC is variations on a folly, a monumental architectural total installation where 19 five-metre-tall columns, also made of cob, rise on a gigantic green stage painted as a chroma key green screen, a technology typically used in the film and advertising industry to create new digital realities. A diffuse sound of pink noise lingers softly in the space. The work is a reference to the colonnade that once led up to the spectacular triumphal arch in Palmyra. There, in present-day Syria, are the ruins of a magnificent city that was once a cultural centre of the ancient world. The triumphal arch was destroyed during the Islamic State’s occupation of Palmyra in 2015. Subsequently it was replicated in marble by the British and American Institute for Digital Archaeology using 3D imaging technology and displayed in Trafalgar Square in London.

About the works, Abbas Akhavan says: “While I am interested in ruins and care about the preservation of cultural heritage, the objective of these works isnot nostalgia for the Iraq Museum or Palmyra Arch, but rather the ways these sites become charged and disturbed as images in the collective imagination.”

Artefacts as cultural migrants

The curatorial objective of the first exhibition focuses on the travelling objects of cultural heritage and the notion of them as ‘cultural migrants’. Objects of cultural heritage are more than just physical traces of a bygone past; they hold their own stories, experiences, journeys and tragedies and, like people, they can become displaced as casualties or agents of war and geopolitical conflict. The exhibition curtain call addresses a range of open-ended questions spanning time, cultural differences and geographical distances. Abbas Akhavan says:

“How do these artefacts circulate through other economies and narratives about re-mapping history, nation building and museum collecting? And what responsibilities do museums and cultural institutions have to history, heritage, artefacts and, more importantly, to the civilians that have produced and cultivated these sites? While Syrian refugees are being kept out of the rest of the world, their artefacts are getting asylum, either in reproduction or in real life.”

The two curators of the exhibition from CC and the Glyptotek supplement:

“Art and cultural artefacts have always migrated across borders as they have been traded and reused in new ways by other cultures and peoples. Today, many of these travelling objects are stored far from their place of origin. In this sense, they can be seen as cultural migrants, living a life today in involuntary diasporas – for example in encyclopaedic museums and private collections around the world,” says Anna Kærsgaard Gregersen, curator at the Glyptotek.

Aukje Lepoutre Ravn, curator at Copenhagen Contemporary, adds: “Like contemporary culture, ancient heritage has thus operated on an international stage. But cultural heritage also plays a central role in the creation of national narratives. So, when artefacts migrate and remove themselves from their original context, difficult questions arise: When cultural heritage is detached from its original context, how and to whom should these artefacts be communicated and create value?”

Curators: Anna Kærsgaard Gregersen, Aukje Lepoutre Ravn.

The joint exhibition programme, Hosting Histories: Revisiting Cultural Heritage of the Middle East and Beyond, gives three international contemporary artists, either residing in the Middle Eastern region or belonging to Middle Eastern diasporas, access to the Glyptotek’s ancient collections and the opportunity to develop a solo exhibition across both institutions. Together with CC and the Glyptotek, the artists will revisit some of history’s silenced and untold stories and – through their own works – bring forward new perspectives on how these stories can be voiced today.

Ghostly revival of lost heritage

The first exhibition in the series is titled curtain call and created by the Montreal-based artist Abbas Akhavan (b. 1977, Tehran). In his first solo exhibition in the Nordic region, Akhavan presents two of his largest installations on view together for the first time: cast for a folly (2019–) and variations on a folly (2021– ). With rustic columns, vibrating green screens and dusty, theatre props, Akhavan re-stages existing architectural sites and historical events displaced in time and place and unsettling in their message.

At the Glyptotek, the installation cast for a folly is shown exactly 20 years after the US invaded Iraq with allied countries including Denmark. The installation is a theatrical staging of a photograph of the lobby of the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad, taken shortly after it was looted during the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The furniture is constructed in fragments and the Assyrian lion sculpture in heavy basalt has been resurrected out of cob, an ancient building material made from sand, clay, water and straw. A kicked-in door has become a green screen, while water lilies float in a plastic container. Now occupying a different time and space, the re-staging of the looted museum asks: Who inherits the ruins of war?

On display at CC is variations on a folly, a monumental architectural total installation where 19 five-metre-tall columns, also made of cob, rise on a gigantic green stage painted as a chroma key green screen, a technology typically used in the film and advertising industry to create new digital realities. A diffuse sound of pink noise lingers softly in the space. The work is a reference to the colonnade that once led up to the spectacular triumphal arch in Palmyra. There, in present-day Syria, are the ruins of a magnificent city that was once a cultural centre of the ancient world. The triumphal arch was destroyed during the Islamic State’s occupation of Palmyra in 2015. Subsequently it was replicated in marble by the British and American Institute for Digital Archaeology using 3D imaging technology and displayed in Trafalgar Square in London.

About the works, Abbas Akhavan says: “While I am interested in ruins and care about the preservation of cultural heritage, the objective of these works isnot nostalgia for the Iraq Museum or Palmyra Arch, but rather the ways these sites become charged and disturbed as images in the collective imagination.”

Artefacts as cultural migrants

The curatorial objective of the first exhibition focuses on the travelling objects of cultural heritage and the notion of them as ‘cultural migrants’. Objects of cultural heritage are more than just physical traces of a bygone past; they hold their own stories, experiences, journeys and tragedies and, like people, they can become displaced as casualties or agents of war and geopolitical conflict. The exhibition curtain call addresses a range of open-ended questions spanning time, cultural differences and geographical distances. Abbas Akhavan says:

“How do these artefacts circulate through other economies and narratives about re-mapping history, nation building and museum collecting? And what responsibilities do museums and cultural institutions have to history, heritage, artefacts and, more importantly, to the civilians that have produced and cultivated these sites? While Syrian refugees are being kept out of the rest of the world, their artefacts are getting asylum, either in reproduction or in real life.”

The two curators of the exhibition from CC and the Glyptotek supplement:

“Art and cultural artefacts have always migrated across borders as they have been traded and reused in new ways by other cultures and peoples. Today, many of these travelling objects are stored far from their place of origin. In this sense, they can be seen as cultural migrants, living a life today in involuntary diasporas – for example in encyclopaedic museums and private collections around the world,” says Anna Kærsgaard Gregersen, curator at the Glyptotek.

Aukje Lepoutre Ravn, curator at Copenhagen Contemporary, adds: “Like contemporary culture, ancient heritage has thus operated on an international stage. But cultural heritage also plays a central role in the creation of national narratives. So, when artefacts migrate and remove themselves from their original context, difficult questions arise: When cultural heritage is detached from its original context, how and to whom should these artefacts be communicated and create value?”

Curators: Anna Kærsgaard Gregersen, Aukje Lepoutre Ravn.