On Glaciers and Avalanches

Irene Kopelman

15 Oct 2017 - 14 Jan 2018

Irene Kopelman “On Glaciers and Avalanches” at CRAC Alsace, 2017

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Irene Kopelman “On Glaciers and Avalanches” at CRAC Alsace, 2017

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Irene Kopelman “On Glaciers and Avalanches” at CRAC Alsace, 2017

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Irene Kopelman “On Glaciers and Avalanches” at CRAC Alsace, 2017

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Irene Kopelman “On Glaciers and Avalanches” at CRAC Alsace, 2017

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Irene Kopelman “On Glaciers and Avalanches” at CRAC Alsace, 2017

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Irene Kopelman “On Glaciers and Avalanches” at CRAC Alsace, 2017

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Irene Kopelman “On Glaciers and Avalanches” at CRAC Alsace, 2017

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Irene Kopelman “On Glaciers and Avalanches” at CRAC Alsace, 2017

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

Courtesy: the artist and Labor, Mexico City. Photo: A. Mole

ON GLACIERS AND AVALANCHES

Irene Kopelman

15 October 2017 - 14 January 2018

Curated by Juan Canela.

Solo exhibition by Irene Kopelman.

If I close my eyes at any point during the day, under any circumstance, I can clearly visualise images that have been etched into my memory. Sometimes they are important ones that bring comfort, that are capable of transporting us to a moment in our lives that makes us feel safe. I like to think of them as a sort of vital pedestal; a base to lean on for support in order to carry on walking.

The first time I saw the drawings of Irene Kopelman (Córdoba, Argentina, 1974) I thought about those pedestal-images. I’m not sure why, but the delicate lines, the abstraction of the shapes, their connection to nature, or their consistent presence made me think about those shapes that I accumulate and carry. It might not be a coincidence, it might have something to do with the fact that her practice is closely connected to the moment when thought and production of knowledge take form. Upon contemplating them, one wonder where they came from, where their origin lies, how they were conformed. They are usually intriguing images that pique our interest. We recognise familiar shapes that we cannot however fully identify. Drawing is an essential element in her work, a medium that articulates thought and allows for the investigation of the notion of the model: attempts to organise life that are the consequence of the human need to study, understand, and order the complexity of the world. These drawings question this, and hint at the impossibility of boxing said complexity into overly narrow categories and divisions.

Kopelman took an early interest in the idea of landscape, so it is no surprise to know that she developed this project in the Alps, the epitome of natural environment, the collective imaginary’s postcard image of a landscape. In her early career, Kopelman worked with the collections of several museums that somehow defended this idea of landscape, only to personally confront it by drawing directly in nature. Later on, she took an interest in the work of scientists from various fields of knowledge, who she would accompany in their travels across the world. Through expeditions to the jungle, journeys through the desert, or mountain climbing excursions, she established a dialogue between disciplines, forms of thinking, ways of looking at the environment, and attempts to understand the world. This relationship with scientists is now an essential part of her practice, and the results of each project –the various drawing or painting series that emerged from them– are the direct consequence of events that occur on her travels, of the vicissitudes connected to the climate, the weather, or logistics. But also of the conversations, exchanges, and the more or less fluid sharing of knowledge, which are without a doubt decisive in the composition of the lines of the drawings.

Kopelman has established collaborations with individuals – like the geologist she went into Colombia’s Tatacoa desert with, for example, or the biologist from the Biodiversity Research Center at the Academia Sínica in Taiwan – or teams such as the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, the Manu Learning Center in the Peruvian jungle, or the expedition on the sailboat Spirit of Sydney, on which she entered Antarctic territory. It was there that she first encountered the challenge of drawing the abrupt shapes in the ice, with their strange and shifting volumes. A couple of years after the expedition to the Antarctic, in October of 2012, Irene Kopelman went to a residency at the Laurenz House Foundation in Basel, where research for this project began. The following summer, once the snow on the mountaintops disappeared, she made her first expeditions to the glaciers of the Alps, where she once again faced the frozen configurations, an experience that marked the beginning of what was to become On Glaciers and Avalanches.

When I first spoke to Irene about the project, one of those image-pedestals immediately came to mind: the Aneto glacier. Located in the Benasque Valley in the middle of the Pyrenees, it was a constant presence in most of my childhood summers. As I traveled the mountains surrounding it, its geometric shape would follow me wherever I went. It is a mutant and unstable image that changes according to the moment of the day, the light shining on it, or the place from which it is viewed. But also because, year after year, the glacier’s surface is diminishing due to global warming. Just like the shifts in the coast of Panama or the movements of the Peruvian jungle’s roof, the retreat of the glaciers is a measure of environmental changes as well as the irreversible effect of humanity on the planet.

While walking in the mountains, one feels insignificant. The mountain prevails, it imposes itself, always. The volumes of rock, ice, and vegetation that surround us reminds our essence that we are part of an ungraspable whole with which we need to establish a dialogue. I was taught to respect the mountains at a young age. To listen, observe, and understand them. You end up loving them, but you can never fully trust them. Even in an environment like that of the Swiss mountains, control over the landscape is an illusion. Nature continues to exceed the human will, just like in any other part of the planet. When an avalanche comes, there is no way of avoiding the impact. During her walks, Kopelman join different scientists as they attempt to understand the landscape, decode it and learn how it functions. Accompanying the team of the del World Glacier Monitoring Service in several expeditions - as well as participating in the Summer School on Mass Balance Measurements and Analysis 2013, she gets a deep insight into different levels of understanding glacier studies. One of the most striking things for her is the use of art-historical sources as a tool for reconstructing past glacier behavior, which lead her into looking at Samuel Birmann (1793-1847) drawings, paying attention to his systems of representation and incorporating certain aspects of it into her own artistic process. –See that material that accumulates on the edge of the glacier? It’s called «moraine»– comments professor Hans Oerlemans (specialist professor in glaciers, sea level, dynamic meteorology and palaeoclimatology at the University of Utrecht) on one of their first climbing expeditions on Morteratschgletscher. Together with Oerlemans, she learned to read the stones and rocks uncovered by the glacier, which reveal how it advances and recedes. Glaciers are large masses of ice that move; snow that is compressed by movement, where the only the laws of physics are at stake; –What will happen with this landscape at a geopolitical level once glaciers disappear, before any one of us has died?– says Wilfried Haeberli (specialist professor in glaciology, geomorphodynamics, and geochronology at the University of Zurich) in one of their conversations. Seeing as a country like Switzerland extracts most of its electric energy from its glaciers, the question is not an irrelevant one; to read the landscape, decipher it, and understand the history of its shape is a language. Lisa Erdle and Alejandro Casteller, from the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research, take samples from the trees using a drill, studying the impact of climate on the landscape. –Did you know that trees grow increasingly taller due to global warming?– she comments at one point in the conversation. Trees are usually no taller than 2,000 metres, but this benchmark seems to be changing.

Knowledge shared with these specialists gives Kopelman the possibility to access the landscape as an artist, to know what to draw in a place that has already been studied and explored in every aspect, run through by civilisation, and represented in every possible way. What can an artist contribute from a place such as this one that might be of significance? The walks, conversations, and experiences in the mountains become a point of access to a great open air laboratory, allowing her to think up a concrete methodology. One that leads her to carefully observe isolated elements of the landscape, different atomised conglomerates that reveal both its complexity and the working process taking place within it. The lines that attempt to replicate lichens, moraine, the shapes of the glacier, the tension between ice and rock, or the various types of trees on the mountainside become witnesses of a history that reveals natural, social, or political aspects that define this place in particular, but which relate to many others.

Whilst in this case the drawings mediate between the mountain and the human, diluting the division between culture and nature, the exhibition is the device– or one of them– which makes them public. We reflect on how to exhibit a work such as this one where time, climate, process, dialogue, and context carry such specific weight, and on the relation between, on the one hand, this methodology, research and production process in the mountains, and on the other, the procedure of conceiving an exhibition space that might communicate the work to the audience. We have attempted to relocate some of the preoccupations inherent to the work–and to the art practice of Irene Kopelman in general– to our working process when devising and articulating the exhibition.

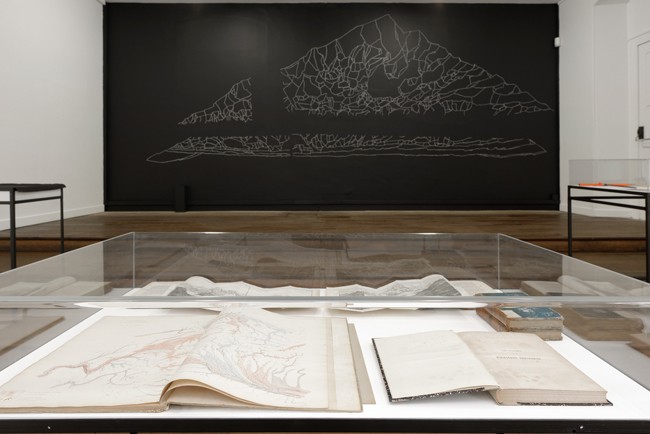

On Glaciers and Avalanches brings together a series of works that derive from expeditions to glaciers carried out between 2012 and 2014, and others made by the artist over the summer to complete the research, with the collaboration of Institut Kunst in Basel. Various series of drawings, watercolours, and paintings unfold on the walls of CRAC Alsace. A new series of porcelain sculptures are placed on the floor in various parts of the museum, as well as various objects and documents from the scientific expeditions.

The building of CRAC Alsace used to be a school, a place that was initially conceived as a space for learning, where the world could be discovered. It contains numerous small rooms of various sizes that are perfect for the distribution of these images from the Swiss mountains nearby, emphasising the fragmented character of the drawings and the production process of the pieces. As its title indicates, the weight of the project falls upon glaciers and the slopes of the mountains whose trees indicate the movement of the avalanches. The number of drawings of each series is defined by the days in each expedition, which may have been be longer or shorter, with better or worse weather, with better or worse visibility. This determines the volume of work and also carries into the installation, spreading out in space not chronologically, but with a spatial and conceptual organization. Four paintings from the Tree Lines (2015) series are placed on either side of the exhibition perimeter, embracing the exhibition. They are views of two opposing mountainsides where Kopelman captured the effect of avalanches in two types of trees that inhabit the area at that altitude. Four days to paint one slope, four days to paint the other. One drawing per day. This idea of facing mountainsides also appears in Tree Lines Davos, Two Slopes from On Top (2013) and Tree Lines Davos, Two Slopes from Below (2014), made with watercolour and colour pencils respectively. They capture the tree masses that define the temperature of the territory and of the action of the avalanches as seen from above and from below. In the second one in particular, the attempt at differentiating the two species of trees is perceptible in the two tones of green. Lichens from Fluhalp (2014) is another series of eight drawings made by the artist when the meteorological conditions prevented her from painting the glaciers. She then decided to concentrate on natural patterns of a different scale such as those made by lichens on rocks, which are oddly similar to those of the glacier. These organisms, which cover large surfaces of territory but usually go unnoticed until one pays attention, may be used to measure air pollution. The purer the air, the more they extend, especially in rocky areas where other species cannot live, absorbing enormous quantities of nitrogen and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and attaching themselves to the ground.

And then, of course, there is the glacier. Together with the series of four drawings View of Grosser Aletschgletscher (2013), where tones of white, brown, and black present different views of the glacier, various series of fragments from different glaciers unfold in the space, distributing and situating alpine geographical points in the rooms. In the central space on the top floor, Gornergletscher From On Top (2014), an installation of 28 drawings, shows the whole glacier through various drawn fragments and the gaps between them. For ten days, the artist drew the areas of the glacier with the most shapes and textures, leaving gaps with no drawing where the surface of the ice was smooth, thus establishing an arbitrary methodology that allowed her to apprehend the landscape and narrow it down. This piece was then used to create a new ceramic sculpture series. Superimposing the shape of the glacier onto the floor plan of CRAC, we selected some of the drawings that, now materialised as volumes, have been spread throughout the rooms, resting on the points of coincidence on the ground.

In a small room the public may browse a copy of Notes on Representation 8, the latest publication from a series published by Roma Publications that accompanies some of Irene Kopelman’s projects. Within it we find a diary of the artist that narrates her working process on the mountains. There are also essays by some of the scientists and images of the works. These publications have become a fundamental part of the projects, generating text around it and functioning as another medium for her work, providing context and a point of access for the public. A body of work that, as many of us have been seeing, covers a field of research that is defined by our relationship with nature and landscape, by an established working routine, a clear practice, and a very precise formalisation. Taking some fixed elements as a starting point, Kopelman yields room to the impossibility of controlling the world, to the ungraspable in knowledge and the need to incorporate other agents into the equation, opening up a range of possibilities to think ourselves in the planet and challenge old dichotomies.

But, which part of what the artist saw on her expeditions ended up on paper and which was omitted? Does she decide or is it the mountains that speak? How can we distribute the works in space so that they may transmit everything they carry? Do we decide or do they?

We cannot be sure of the answers, but perhaps next time you close your eyes, the fragment of a glacier will appear in your mind.

- J. C., August 2017.

On Glaciers and Avalanches is organised with the support of Mondriaan Funds, Foundation Laurenz House and with the collaboration of Institut Kunst HGK FHNW, Basel. This exhibition is part of Oh ! Pays-Bas saison culturelle néerlandaise en France 2017-2018.

Irene Kopelman

15 October 2017 - 14 January 2018

Curated by Juan Canela.

Solo exhibition by Irene Kopelman.

If I close my eyes at any point during the day, under any circumstance, I can clearly visualise images that have been etched into my memory. Sometimes they are important ones that bring comfort, that are capable of transporting us to a moment in our lives that makes us feel safe. I like to think of them as a sort of vital pedestal; a base to lean on for support in order to carry on walking.

The first time I saw the drawings of Irene Kopelman (Córdoba, Argentina, 1974) I thought about those pedestal-images. I’m not sure why, but the delicate lines, the abstraction of the shapes, their connection to nature, or their consistent presence made me think about those shapes that I accumulate and carry. It might not be a coincidence, it might have something to do with the fact that her practice is closely connected to the moment when thought and production of knowledge take form. Upon contemplating them, one wonder where they came from, where their origin lies, how they were conformed. They are usually intriguing images that pique our interest. We recognise familiar shapes that we cannot however fully identify. Drawing is an essential element in her work, a medium that articulates thought and allows for the investigation of the notion of the model: attempts to organise life that are the consequence of the human need to study, understand, and order the complexity of the world. These drawings question this, and hint at the impossibility of boxing said complexity into overly narrow categories and divisions.

Kopelman took an early interest in the idea of landscape, so it is no surprise to know that she developed this project in the Alps, the epitome of natural environment, the collective imaginary’s postcard image of a landscape. In her early career, Kopelman worked with the collections of several museums that somehow defended this idea of landscape, only to personally confront it by drawing directly in nature. Later on, she took an interest in the work of scientists from various fields of knowledge, who she would accompany in their travels across the world. Through expeditions to the jungle, journeys through the desert, or mountain climbing excursions, she established a dialogue between disciplines, forms of thinking, ways of looking at the environment, and attempts to understand the world. This relationship with scientists is now an essential part of her practice, and the results of each project –the various drawing or painting series that emerged from them– are the direct consequence of events that occur on her travels, of the vicissitudes connected to the climate, the weather, or logistics. But also of the conversations, exchanges, and the more or less fluid sharing of knowledge, which are without a doubt decisive in the composition of the lines of the drawings.

Kopelman has established collaborations with individuals – like the geologist she went into Colombia’s Tatacoa desert with, for example, or the biologist from the Biodiversity Research Center at the Academia Sínica in Taiwan – or teams such as the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, the Manu Learning Center in the Peruvian jungle, or the expedition on the sailboat Spirit of Sydney, on which she entered Antarctic territory. It was there that she first encountered the challenge of drawing the abrupt shapes in the ice, with their strange and shifting volumes. A couple of years after the expedition to the Antarctic, in October of 2012, Irene Kopelman went to a residency at the Laurenz House Foundation in Basel, where research for this project began. The following summer, once the snow on the mountaintops disappeared, she made her first expeditions to the glaciers of the Alps, where she once again faced the frozen configurations, an experience that marked the beginning of what was to become On Glaciers and Avalanches.

When I first spoke to Irene about the project, one of those image-pedestals immediately came to mind: the Aneto glacier. Located in the Benasque Valley in the middle of the Pyrenees, it was a constant presence in most of my childhood summers. As I traveled the mountains surrounding it, its geometric shape would follow me wherever I went. It is a mutant and unstable image that changes according to the moment of the day, the light shining on it, or the place from which it is viewed. But also because, year after year, the glacier’s surface is diminishing due to global warming. Just like the shifts in the coast of Panama or the movements of the Peruvian jungle’s roof, the retreat of the glaciers is a measure of environmental changes as well as the irreversible effect of humanity on the planet.

While walking in the mountains, one feels insignificant. The mountain prevails, it imposes itself, always. The volumes of rock, ice, and vegetation that surround us reminds our essence that we are part of an ungraspable whole with which we need to establish a dialogue. I was taught to respect the mountains at a young age. To listen, observe, and understand them. You end up loving them, but you can never fully trust them. Even in an environment like that of the Swiss mountains, control over the landscape is an illusion. Nature continues to exceed the human will, just like in any other part of the planet. When an avalanche comes, there is no way of avoiding the impact. During her walks, Kopelman join different scientists as they attempt to understand the landscape, decode it and learn how it functions. Accompanying the team of the del World Glacier Monitoring Service in several expeditions - as well as participating in the Summer School on Mass Balance Measurements and Analysis 2013, she gets a deep insight into different levels of understanding glacier studies. One of the most striking things for her is the use of art-historical sources as a tool for reconstructing past glacier behavior, which lead her into looking at Samuel Birmann (1793-1847) drawings, paying attention to his systems of representation and incorporating certain aspects of it into her own artistic process. –See that material that accumulates on the edge of the glacier? It’s called «moraine»– comments professor Hans Oerlemans (specialist professor in glaciers, sea level, dynamic meteorology and palaeoclimatology at the University of Utrecht) on one of their first climbing expeditions on Morteratschgletscher. Together with Oerlemans, she learned to read the stones and rocks uncovered by the glacier, which reveal how it advances and recedes. Glaciers are large masses of ice that move; snow that is compressed by movement, where the only the laws of physics are at stake; –What will happen with this landscape at a geopolitical level once glaciers disappear, before any one of us has died?– says Wilfried Haeberli (specialist professor in glaciology, geomorphodynamics, and geochronology at the University of Zurich) in one of their conversations. Seeing as a country like Switzerland extracts most of its electric energy from its glaciers, the question is not an irrelevant one; to read the landscape, decipher it, and understand the history of its shape is a language. Lisa Erdle and Alejandro Casteller, from the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research, take samples from the trees using a drill, studying the impact of climate on the landscape. –Did you know that trees grow increasingly taller due to global warming?– she comments at one point in the conversation. Trees are usually no taller than 2,000 metres, but this benchmark seems to be changing.

Knowledge shared with these specialists gives Kopelman the possibility to access the landscape as an artist, to know what to draw in a place that has already been studied and explored in every aspect, run through by civilisation, and represented in every possible way. What can an artist contribute from a place such as this one that might be of significance? The walks, conversations, and experiences in the mountains become a point of access to a great open air laboratory, allowing her to think up a concrete methodology. One that leads her to carefully observe isolated elements of the landscape, different atomised conglomerates that reveal both its complexity and the working process taking place within it. The lines that attempt to replicate lichens, moraine, the shapes of the glacier, the tension between ice and rock, or the various types of trees on the mountainside become witnesses of a history that reveals natural, social, or political aspects that define this place in particular, but which relate to many others.

Whilst in this case the drawings mediate between the mountain and the human, diluting the division between culture and nature, the exhibition is the device– or one of them– which makes them public. We reflect on how to exhibit a work such as this one where time, climate, process, dialogue, and context carry such specific weight, and on the relation between, on the one hand, this methodology, research and production process in the mountains, and on the other, the procedure of conceiving an exhibition space that might communicate the work to the audience. We have attempted to relocate some of the preoccupations inherent to the work–and to the art practice of Irene Kopelman in general– to our working process when devising and articulating the exhibition.

On Glaciers and Avalanches brings together a series of works that derive from expeditions to glaciers carried out between 2012 and 2014, and others made by the artist over the summer to complete the research, with the collaboration of Institut Kunst in Basel. Various series of drawings, watercolours, and paintings unfold on the walls of CRAC Alsace. A new series of porcelain sculptures are placed on the floor in various parts of the museum, as well as various objects and documents from the scientific expeditions.

The building of CRAC Alsace used to be a school, a place that was initially conceived as a space for learning, where the world could be discovered. It contains numerous small rooms of various sizes that are perfect for the distribution of these images from the Swiss mountains nearby, emphasising the fragmented character of the drawings and the production process of the pieces. As its title indicates, the weight of the project falls upon glaciers and the slopes of the mountains whose trees indicate the movement of the avalanches. The number of drawings of each series is defined by the days in each expedition, which may have been be longer or shorter, with better or worse weather, with better or worse visibility. This determines the volume of work and also carries into the installation, spreading out in space not chronologically, but with a spatial and conceptual organization. Four paintings from the Tree Lines (2015) series are placed on either side of the exhibition perimeter, embracing the exhibition. They are views of two opposing mountainsides where Kopelman captured the effect of avalanches in two types of trees that inhabit the area at that altitude. Four days to paint one slope, four days to paint the other. One drawing per day. This idea of facing mountainsides also appears in Tree Lines Davos, Two Slopes from On Top (2013) and Tree Lines Davos, Two Slopes from Below (2014), made with watercolour and colour pencils respectively. They capture the tree masses that define the temperature of the territory and of the action of the avalanches as seen from above and from below. In the second one in particular, the attempt at differentiating the two species of trees is perceptible in the two tones of green. Lichens from Fluhalp (2014) is another series of eight drawings made by the artist when the meteorological conditions prevented her from painting the glaciers. She then decided to concentrate on natural patterns of a different scale such as those made by lichens on rocks, which are oddly similar to those of the glacier. These organisms, which cover large surfaces of territory but usually go unnoticed until one pays attention, may be used to measure air pollution. The purer the air, the more they extend, especially in rocky areas where other species cannot live, absorbing enormous quantities of nitrogen and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and attaching themselves to the ground.

And then, of course, there is the glacier. Together with the series of four drawings View of Grosser Aletschgletscher (2013), where tones of white, brown, and black present different views of the glacier, various series of fragments from different glaciers unfold in the space, distributing and situating alpine geographical points in the rooms. In the central space on the top floor, Gornergletscher From On Top (2014), an installation of 28 drawings, shows the whole glacier through various drawn fragments and the gaps between them. For ten days, the artist drew the areas of the glacier with the most shapes and textures, leaving gaps with no drawing where the surface of the ice was smooth, thus establishing an arbitrary methodology that allowed her to apprehend the landscape and narrow it down. This piece was then used to create a new ceramic sculpture series. Superimposing the shape of the glacier onto the floor plan of CRAC, we selected some of the drawings that, now materialised as volumes, have been spread throughout the rooms, resting on the points of coincidence on the ground.

In a small room the public may browse a copy of Notes on Representation 8, the latest publication from a series published by Roma Publications that accompanies some of Irene Kopelman’s projects. Within it we find a diary of the artist that narrates her working process on the mountains. There are also essays by some of the scientists and images of the works. These publications have become a fundamental part of the projects, generating text around it and functioning as another medium for her work, providing context and a point of access for the public. A body of work that, as many of us have been seeing, covers a field of research that is defined by our relationship with nature and landscape, by an established working routine, a clear practice, and a very precise formalisation. Taking some fixed elements as a starting point, Kopelman yields room to the impossibility of controlling the world, to the ungraspable in knowledge and the need to incorporate other agents into the equation, opening up a range of possibilities to think ourselves in the planet and challenge old dichotomies.

But, which part of what the artist saw on her expeditions ended up on paper and which was omitted? Does she decide or is it the mountains that speak? How can we distribute the works in space so that they may transmit everything they carry? Do we decide or do they?

We cannot be sure of the answers, but perhaps next time you close your eyes, the fragment of a glacier will appear in your mind.

- J. C., August 2017.

On Glaciers and Avalanches is organised with the support of Mondriaan Funds, Foundation Laurenz House and with the collaboration of Institut Kunst HGK FHNW, Basel. This exhibition is part of Oh ! Pays-Bas saison culturelle néerlandaise en France 2017-2018.