Chris Ofili

20 Sep - 03 Nov 2007

CHRIS OFILI

"Devil’s Pie"

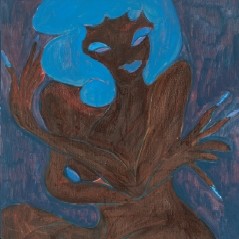

Opening on September 20, 2007, David Zwirner is pleased to present an exhibition of new work by artist Chris Ofili, who lives and works in Trinidad. This will be Ofili’s debut solo exhibition at David Zwirner and the first to unite his work in painting, sculpture, printmaking, and graphite drawing. A fully illustrated catalogue will be published by Steidl/David Zwirner in conjunction with the exhibition. Ofili began to garner attention in the mid-1990s with his intricately constructed works, combining bead-like dots of paint, informed in part by cave paintings in Zimbabwe, with collaged images from popular media, and elephant dung. Despite shifts in his material choices, the artist has remained committed to a painting process that relies on deliberate flattening of the picture plane, carefully layered surfaces, and diffuse sources of inspiration. Over the years, both formally and conceptually, Ofili has paid homage and forged dialogue with works by artists ranging from William Hogarth, Philip Guston, Henri Matisse, William Blake, to the Blue Rider group. In this exhibition, Ofili continues, in a variety of media, his active engagement with art history and traditions of representation. Throughout the exhibition, Ofili repeats, recombines, and reassesses his subjects, ultimately reinforcing the multivalence of his imagery and the interconnectedness of its underlying themes: birth, death, seduction, and salvation, both religious and personal. In Lazarus (dream), 2007, Ofili pairs the biblical character of Lazarus, the man whom Christ miraculously raised from the dead (prefiguring Jesus’ own resurrection) and who appears on five canvases, with an image of a dancing couple drawn from the iconic photograph, Christmas Eve, 1963, by Malian photographer Malick Sidibй. The temporal, spatial, and iconographic juxtaposition of the resurrected old man and the young celebratory couple begs the viewer to consider birth, rebirth, and the numerous possible permutations, stages, and cycles of life. In another painting, Douen’s Dance, 2007, Ofili again riffs on the Sidibй image, which appears in three paintings on canvas and one collage on linen, this time combining it with aspects of Trinidadian folklore, establishing the heavy influence the artist’s current home has exerted on the development of this new body of work. According to island myth, children who die prior to their baptism reappear as spirits on earth; these spirits, known as douens, can be recognized by their backwards facing feet, marking their inability to move into the next life. By inverting the foot of the female figure in Douen’s Dance, Ofili subtly infuses the familiar image of the couple with new meaning, blending disparate traditions to create a rich and unique iconography. Similarly, in creating Confession (Lady Chancellor), 2007, Ofili found inspiration in art historical depictions of the “penitent whore” Mary Magdalene (with her red hair used to dry the feet of Christ), images of nudes from Playboy Magazine (the disembodied hand offering a drink), and Trinidad’s Lady Chancellor Hill (the outline is formed by the arch of the figure’s back), thus creating a complicated portrait of temptation, sin, and the admission of guilt.

For this exhibition, Ofili has created six sculptures in bronze. Despite some very early work in three dimensions, the artist began seriously exploring the medium of sculpture for his Blue Rider exhibition in 2005. Ofili further refines his practice in the current exhibition with complexly articulated figures, vast differences in scale, and varying treatments of his materials. Two of these works tackle the subject of the Annunciation, when, according to Biblical accounts, the Angel Gabriel revealed to the Virgin Mary that she would bear the Son of God; one sculpture depicts the couple kneeling and the other standing, capturing perhaps two different moments or two distinctive ways of imagining the interaction. In both sculptures, the dark matte bronze of the Angel contrasts the smoothly polished, gleaming bronze of the Virgin, underscoring the psychological drama which unfolds between his subjects. While the reflective surface readily conjures the idea of purity, often associated with the figure of Mary, it is the darker bronze of the Angel that is technically the less treated, and thus purer of the two metals, potentially challenging viewers’ understanding of innocence and experience. Similarly, Ofili’s sexually explicit and dynamic manipulation of the two figures, at times blending into one, prompts viewers to question their perceptions of push versus pull, active versus passive, sacred versus profane. In Saint Sebastian, 2007, Ofili further integrates the abstract notion of time into his sculptural practice, managing to capture the fleeting moments of transition and liminality of his subject. One of the most widely depicted saints throughout the late Gothic and Renaissance period, Saint Sebastian was persecuted and sentenced to death by arrows, but did not die (he was later successfully beaten to death at the Emperor’s command). Ofili depicts Saint Sebastian in the throws of martyrdom, replacing the arrows, traditionally associated with the figure of the saint, with nails, calling to mind the Minkisi Minkondi sculptures of the Bakongo tribe. These African tools of moral revelation, activated by the addition of nails and other materials, have the primary purpose of exposing witches, adulterers, thieves, and other wrongdoers. By combining references to Saint Sebastian, whose spirit was intended to be defeated by arrows, with the Minkisi Minkondi, whose spirit is provoked by nails, Ofili creates a figure in physiological, psychological, and spiritual flux. For the exhibition, Ofili also created a suite of graphite drawings, 7 Brides for 7 Bros, 2006, inspired by Stanley Donen’s 1954 musical, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, a filmic adaptation of Stephen Vincent Benet’s short story, The Sobbin’ Women, based on the Roman myth, The Rape of the Sabines, completing the circle of influence. Directly referencing the movie through the titles of his subjects (each of Ofili’s women is named after her filmic betrothed), the artist furthers the connection using his signature “afro heads” to create the nimble figures, evoking the bold angles and lithe arabesques of the film’s fanciful choreography. A mainstay of Ofili’s drawing practice, the “afro head” assumes new significance in the context of The Agony in the Garden, 2007, a suite of eleven intaglio prints. Set in the Garden of Gethsemane, each print depicts the same moment, when Judas betrayed Christ with a kiss, from the varying viewpoints of the eleven other disciples. Ofili employs the heads, leaving some as outlines while others are filled in, to represent the eleven perspectives amidst the throng of soldiers that accompanied Judas to capture Christ and ultimately sentence him to crucifixion. Through this gesture, Ofili reinforces the power of perspective, acknowledging that any story, even one of history’s most frequently told, is simply one attempt at describing the apparent truth of the situation. The exhibition title, Devil’s Pie, is derived from singer-songwriter D’Angelo’s 1998 lyrical meditation on temptation and retribution, reaffirming the artist’s longstanding relationship with music, especially hip-hop sounds and culture, as well as his continued exploration of Biblical themes, as demonstrated throughout the exhibition. According to the song, the ingredients of this metaphorical dish include “materialistic, greed and lust, jealousy, envious/bread and dough, cheddar cheese, flash and stash, cash and cream.” While addressing specific aspects of the black urban experience, the song maintains a universal significance, questioning the nature of sin, desire, and redemption. Likewise, in its diverse references and inextricable dichotomies, Ofili’s work functions as a magnet for viewers’ own meanings, ideas, or arguments and encourages them to disagree freely, even with themselves.

"Devil’s Pie"

Opening on September 20, 2007, David Zwirner is pleased to present an exhibition of new work by artist Chris Ofili, who lives and works in Trinidad. This will be Ofili’s debut solo exhibition at David Zwirner and the first to unite his work in painting, sculpture, printmaking, and graphite drawing. A fully illustrated catalogue will be published by Steidl/David Zwirner in conjunction with the exhibition. Ofili began to garner attention in the mid-1990s with his intricately constructed works, combining bead-like dots of paint, informed in part by cave paintings in Zimbabwe, with collaged images from popular media, and elephant dung. Despite shifts in his material choices, the artist has remained committed to a painting process that relies on deliberate flattening of the picture plane, carefully layered surfaces, and diffuse sources of inspiration. Over the years, both formally and conceptually, Ofili has paid homage and forged dialogue with works by artists ranging from William Hogarth, Philip Guston, Henri Matisse, William Blake, to the Blue Rider group. In this exhibition, Ofili continues, in a variety of media, his active engagement with art history and traditions of representation. Throughout the exhibition, Ofili repeats, recombines, and reassesses his subjects, ultimately reinforcing the multivalence of his imagery and the interconnectedness of its underlying themes: birth, death, seduction, and salvation, both religious and personal. In Lazarus (dream), 2007, Ofili pairs the biblical character of Lazarus, the man whom Christ miraculously raised from the dead (prefiguring Jesus’ own resurrection) and who appears on five canvases, with an image of a dancing couple drawn from the iconic photograph, Christmas Eve, 1963, by Malian photographer Malick Sidibй. The temporal, spatial, and iconographic juxtaposition of the resurrected old man and the young celebratory couple begs the viewer to consider birth, rebirth, and the numerous possible permutations, stages, and cycles of life. In another painting, Douen’s Dance, 2007, Ofili again riffs on the Sidibй image, which appears in three paintings on canvas and one collage on linen, this time combining it with aspects of Trinidadian folklore, establishing the heavy influence the artist’s current home has exerted on the development of this new body of work. According to island myth, children who die prior to their baptism reappear as spirits on earth; these spirits, known as douens, can be recognized by their backwards facing feet, marking their inability to move into the next life. By inverting the foot of the female figure in Douen’s Dance, Ofili subtly infuses the familiar image of the couple with new meaning, blending disparate traditions to create a rich and unique iconography. Similarly, in creating Confession (Lady Chancellor), 2007, Ofili found inspiration in art historical depictions of the “penitent whore” Mary Magdalene (with her red hair used to dry the feet of Christ), images of nudes from Playboy Magazine (the disembodied hand offering a drink), and Trinidad’s Lady Chancellor Hill (the outline is formed by the arch of the figure’s back), thus creating a complicated portrait of temptation, sin, and the admission of guilt.

For this exhibition, Ofili has created six sculptures in bronze. Despite some very early work in three dimensions, the artist began seriously exploring the medium of sculpture for his Blue Rider exhibition in 2005. Ofili further refines his practice in the current exhibition with complexly articulated figures, vast differences in scale, and varying treatments of his materials. Two of these works tackle the subject of the Annunciation, when, according to Biblical accounts, the Angel Gabriel revealed to the Virgin Mary that she would bear the Son of God; one sculpture depicts the couple kneeling and the other standing, capturing perhaps two different moments or two distinctive ways of imagining the interaction. In both sculptures, the dark matte bronze of the Angel contrasts the smoothly polished, gleaming bronze of the Virgin, underscoring the psychological drama which unfolds between his subjects. While the reflective surface readily conjures the idea of purity, often associated with the figure of Mary, it is the darker bronze of the Angel that is technically the less treated, and thus purer of the two metals, potentially challenging viewers’ understanding of innocence and experience. Similarly, Ofili’s sexually explicit and dynamic manipulation of the two figures, at times blending into one, prompts viewers to question their perceptions of push versus pull, active versus passive, sacred versus profane. In Saint Sebastian, 2007, Ofili further integrates the abstract notion of time into his sculptural practice, managing to capture the fleeting moments of transition and liminality of his subject. One of the most widely depicted saints throughout the late Gothic and Renaissance period, Saint Sebastian was persecuted and sentenced to death by arrows, but did not die (he was later successfully beaten to death at the Emperor’s command). Ofili depicts Saint Sebastian in the throws of martyrdom, replacing the arrows, traditionally associated with the figure of the saint, with nails, calling to mind the Minkisi Minkondi sculptures of the Bakongo tribe. These African tools of moral revelation, activated by the addition of nails and other materials, have the primary purpose of exposing witches, adulterers, thieves, and other wrongdoers. By combining references to Saint Sebastian, whose spirit was intended to be defeated by arrows, with the Minkisi Minkondi, whose spirit is provoked by nails, Ofili creates a figure in physiological, psychological, and spiritual flux. For the exhibition, Ofili also created a suite of graphite drawings, 7 Brides for 7 Bros, 2006, inspired by Stanley Donen’s 1954 musical, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, a filmic adaptation of Stephen Vincent Benet’s short story, The Sobbin’ Women, based on the Roman myth, The Rape of the Sabines, completing the circle of influence. Directly referencing the movie through the titles of his subjects (each of Ofili’s women is named after her filmic betrothed), the artist furthers the connection using his signature “afro heads” to create the nimble figures, evoking the bold angles and lithe arabesques of the film’s fanciful choreography. A mainstay of Ofili’s drawing practice, the “afro head” assumes new significance in the context of The Agony in the Garden, 2007, a suite of eleven intaglio prints. Set in the Garden of Gethsemane, each print depicts the same moment, when Judas betrayed Christ with a kiss, from the varying viewpoints of the eleven other disciples. Ofili employs the heads, leaving some as outlines while others are filled in, to represent the eleven perspectives amidst the throng of soldiers that accompanied Judas to capture Christ and ultimately sentence him to crucifixion. Through this gesture, Ofili reinforces the power of perspective, acknowledging that any story, even one of history’s most frequently told, is simply one attempt at describing the apparent truth of the situation. The exhibition title, Devil’s Pie, is derived from singer-songwriter D’Angelo’s 1998 lyrical meditation on temptation and retribution, reaffirming the artist’s longstanding relationship with music, especially hip-hop sounds and culture, as well as his continued exploration of Biblical themes, as demonstrated throughout the exhibition. According to the song, the ingredients of this metaphorical dish include “materialistic, greed and lust, jealousy, envious/bread and dough, cheddar cheese, flash and stash, cash and cream.” While addressing specific aspects of the black urban experience, the song maintains a universal significance, questioning the nature of sin, desire, and redemption. Likewise, in its diverse references and inextricable dichotomies, Ofili’s work functions as a magnet for viewers’ own meanings, ideas, or arguments and encourages them to disagree freely, even with themselves.