Matthew Barney and Joseph Beuys

28 Oct 2006 - 12 Jan 2007

Matthew Barney and Joseph Beuys

all in the present must be transformed

28 Oct 2006 - 12 Jan 2007

all in the present must be transformed: Matthew Barney and Joseph Beuys examines affinities between the two artists, who, though separated by generation and geography, share aesthetic and conceptual concerns. The exhibition focuses on the metaphoric use of materials, the belief in metamorphosis, and the relationship between action and its documentation in their respective practices. It also reveals fundamental, philosophical differences between Barney and Beuys—fueled, no doubt, by the divide between modern and postmodernist thought—that, in turn, further enhances our understanding of each artist’s work.

Sculpture

Assembled during a performance in Rome as a benefit for the Italian newspaper Lotta Continua, Beuys’s Terremoto (1981) conflates key narrative threads. The type-setting machine refers to the power of newsprint to diffuse ideas on a massive scale. The manifestos affixed to the press relate to theories of social activism, environmental sustainability, and freedom of expression. Beuys spread fat, his signature material, on the keyboard, metaphorically ascribing the tools for communication with a source of energy to insure the transmission of ideas. He wrapped an Italian flag in felt in a gesture informed by his association of the material with insulation and healing. The blackboards, covered with drawings of human heads, their mouths open in silent screams, allude to the victims of the earthquake that struck Naples in 1980, to which the title of the work refers.

Barney’s Chrysler Imperial (2002) encapsulates sequences from the final film of his five-part CREMASTER cycle (1994-2003), which summarizes his essential themes. Each of the five main components, abstracted from cars competing in a demolition derby set in the lobby of the Chrysler Building, ca. 1930, bears the insignia of a specific CREMASTER episode and embodies the conflicts explored in the film cycle. As an abridged version of the cycle, Chrysler Imperial exemplifies how Barney distills cinematic narrative into sculptural dimensions—using his signature Vaseline and cast plastics—to extrapolate in space what he explores in time.

Beuys’s sculpture Eurasienstab (Eurasian Staff) (1967-68) derives from a series of actions around the theme of “Eurasia”, including a 1968 performance in Antwerp, documented in the video on view here. Beuys’s concept of “Eurasia” sought to elide the ancient cultural boundaries between East and West, referring also to a divided Germany. For him, the staff was a conductor of energy linking Eastern transcendentalism with Western rationalism.

Barney’s first installation, Field Dressing (1989-90) fuses performance, video, and sculpture in an equation that has informed all of his subsequent work. The video monitors reveal actions that Barney performed by interacting with the sculptural elements on view, invoking the hubristic yearnings of extreme athletics, the attempt to create form through resistance, and the idea of potentiality unleashed through discipline.

Vitrines

Beuys’s vitrines evoke the display mechanisms of both the fine art and natural history museum. The dual reference forwards his argument that art cannot be understood separately from either the social or organic worlds. The vitrine from 1983 includes Fat Filter (1964) and Sledge (1969), a multiple that invokes the theme of survival at the core of Beuys’s personal mythology. Another vitrine from 1984 features artifacts from a 1974 action in Pescara titled Incontro con Beuys, which refer to his concepts of insulation and energy production: a copper plate wrapped in felt and Italian sausages that Beuys sliced during the performance.

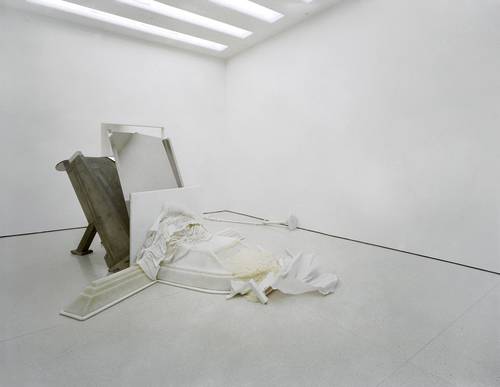

For Barney, the vitrine offered a solution for the presentation of his editioned CREMASTER films as sculpture. CREMASTER 2 (1999), which deployed the story of Mormon murderer Gary Gilmore as a narrative armature, engendered a vitrine lined with honeycomb—a reference to Utah’s emblem of the beehive. CREMASTER 3 (2002), which utilizes the partition of Ireland as a structural element, generated a vitrine constructed from green and orange plastic, the colors of the Irish flag.

Drawings

Drawing is central to both artists’ oeuvres. Whether emanating from existing work, preceding it in a catalytic manner, or being realized as part of a performance, drawing reveals the conceptual underpinnings of their practices. Iconographically, the drawings chart each artist’s absorption in transformative processes and personal cosmologies. Beuys used the cruciform as a graphic symbol for his belief that art could function as a therapeutic force in the world. As a logo, it relates to Barney’s use of the “field emblem” as an identifying marker in his work. An ellipsis bisected horizontally by a single bar, the symbol represents a body disciplined by restraint, a flow of raw energy held in check, an arena of pure potential.

www.deutsche-guggenheim.de

© Matthew Barney

Cremaster 2, 1999

Silkscreened digital video disk, nylon, tooled saddle leather, sterling silver, beeswax, polycarbonate honeycomb, acrylic, and nylon vitrine, with 35mm print; digital video transferred to film with audio, 1:19:00

Edition 8/10

Vitrine: 38 3/8 x 40 x 46 5/8 inches / 97.5 x 101.6 x 118.4 cm

Photo by Ellen Labenski

© The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

all in the present must be transformed

28 Oct 2006 - 12 Jan 2007

all in the present must be transformed: Matthew Barney and Joseph Beuys examines affinities between the two artists, who, though separated by generation and geography, share aesthetic and conceptual concerns. The exhibition focuses on the metaphoric use of materials, the belief in metamorphosis, and the relationship between action and its documentation in their respective practices. It also reveals fundamental, philosophical differences between Barney and Beuys—fueled, no doubt, by the divide between modern and postmodernist thought—that, in turn, further enhances our understanding of each artist’s work.

Sculpture

Assembled during a performance in Rome as a benefit for the Italian newspaper Lotta Continua, Beuys’s Terremoto (1981) conflates key narrative threads. The type-setting machine refers to the power of newsprint to diffuse ideas on a massive scale. The manifestos affixed to the press relate to theories of social activism, environmental sustainability, and freedom of expression. Beuys spread fat, his signature material, on the keyboard, metaphorically ascribing the tools for communication with a source of energy to insure the transmission of ideas. He wrapped an Italian flag in felt in a gesture informed by his association of the material with insulation and healing. The blackboards, covered with drawings of human heads, their mouths open in silent screams, allude to the victims of the earthquake that struck Naples in 1980, to which the title of the work refers.

Barney’s Chrysler Imperial (2002) encapsulates sequences from the final film of his five-part CREMASTER cycle (1994-2003), which summarizes his essential themes. Each of the five main components, abstracted from cars competing in a demolition derby set in the lobby of the Chrysler Building, ca. 1930, bears the insignia of a specific CREMASTER episode and embodies the conflicts explored in the film cycle. As an abridged version of the cycle, Chrysler Imperial exemplifies how Barney distills cinematic narrative into sculptural dimensions—using his signature Vaseline and cast plastics—to extrapolate in space what he explores in time.

Beuys’s sculpture Eurasienstab (Eurasian Staff) (1967-68) derives from a series of actions around the theme of “Eurasia”, including a 1968 performance in Antwerp, documented in the video on view here. Beuys’s concept of “Eurasia” sought to elide the ancient cultural boundaries between East and West, referring also to a divided Germany. For him, the staff was a conductor of energy linking Eastern transcendentalism with Western rationalism.

Barney’s first installation, Field Dressing (1989-90) fuses performance, video, and sculpture in an equation that has informed all of his subsequent work. The video monitors reveal actions that Barney performed by interacting with the sculptural elements on view, invoking the hubristic yearnings of extreme athletics, the attempt to create form through resistance, and the idea of potentiality unleashed through discipline.

Vitrines

Beuys’s vitrines evoke the display mechanisms of both the fine art and natural history museum. The dual reference forwards his argument that art cannot be understood separately from either the social or organic worlds. The vitrine from 1983 includes Fat Filter (1964) and Sledge (1969), a multiple that invokes the theme of survival at the core of Beuys’s personal mythology. Another vitrine from 1984 features artifacts from a 1974 action in Pescara titled Incontro con Beuys, which refer to his concepts of insulation and energy production: a copper plate wrapped in felt and Italian sausages that Beuys sliced during the performance.

For Barney, the vitrine offered a solution for the presentation of his editioned CREMASTER films as sculpture. CREMASTER 2 (1999), which deployed the story of Mormon murderer Gary Gilmore as a narrative armature, engendered a vitrine lined with honeycomb—a reference to Utah’s emblem of the beehive. CREMASTER 3 (2002), which utilizes the partition of Ireland as a structural element, generated a vitrine constructed from green and orange plastic, the colors of the Irish flag.

Drawings

Drawing is central to both artists’ oeuvres. Whether emanating from existing work, preceding it in a catalytic manner, or being realized as part of a performance, drawing reveals the conceptual underpinnings of their practices. Iconographically, the drawings chart each artist’s absorption in transformative processes and personal cosmologies. Beuys used the cruciform as a graphic symbol for his belief that art could function as a therapeutic force in the world. As a logo, it relates to Barney’s use of the “field emblem” as an identifying marker in his work. An ellipsis bisected horizontally by a single bar, the symbol represents a body disciplined by restraint, a flow of raw energy held in check, an arena of pure potential.

www.deutsche-guggenheim.de

© Matthew Barney

Cremaster 2, 1999

Silkscreened digital video disk, nylon, tooled saddle leather, sterling silver, beeswax, polycarbonate honeycomb, acrylic, and nylon vitrine, with 35mm print; digital video transferred to film with audio, 1:19:00

Edition 8/10

Vitrine: 38 3/8 x 40 x 46 5/8 inches / 97.5 x 101.6 x 118.4 cm

Photo by Ellen Labenski

© The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York