Vered Nachmani

30 Oct - 11 Dec 2010

© Vered Nachmani

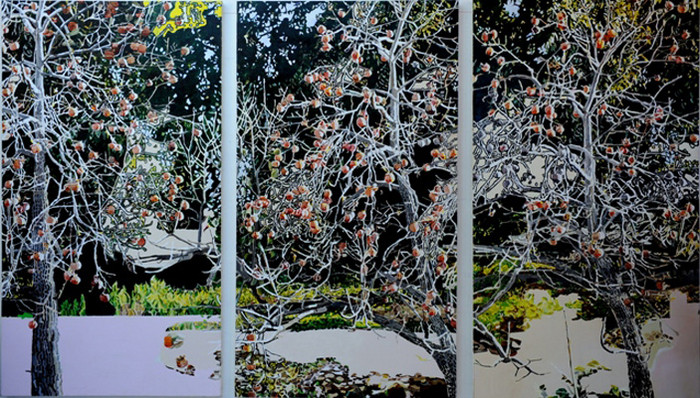

View of the Persimmon Grove, first, second and third panels, 2010

acrylic on canvas

100x180 cm

View of the Persimmon Grove, first, second and third panels, 2010

acrylic on canvas

100x180 cm

VERED NACHMANI

Place Filler

October 30th- December 11th, 2010

One autumn day of 2006, Vered Nachmani encountered a persimmon grove which was to become the subject of her forthcoming exhibition. The persimmon trees, divested of their foliage, their rotting fruit still hanging on the branches or lying at their foot, were lit by early evening sunbeams. The impression, which she briefly absorbed and has cherished since, was further intensified by the presence of a large gloomy nut tree at the rear end of the naked plantation. Several times she returned there, tying in vain to capture a similar moment with her camera. The fleeting sight she had glimpsed – a combination of sunset glows, evening shadows and rotting fruit – set itself in her memory. It is fair to say then, that in her current series of paintings she tries to reproduce this fleeting moment.

An ongoing acquaintance with the paintings of Vered Nachmani yields a number of insights pertaining to the characteristics of her work: she paints from photographs, and divides her canvas using a grid; the resulting surfaces are filled with color in a progressive manner, and the light source is given meticulous treatment – steps that are taken primarily to maintain a faithfulness to the source image. However, in recent years her paintings have loosened their grip on reality and showed a growing tendency towards expressive figuration and abstraction. If we look at the persimmons as a microcosm of Nachmani’s painting, then a reversal of priorities becomes apparent. Nachmani approaches the persimmons as in classical still-life paintings, yet she testifies to a will “to depict them with single brush-strokes, ones that enable a fresh and liberated expression that ‘gives a persimmon’ – without volume or an attempted illusionism; a persimmon more faithful to the application of color on the canvas than it is to nature”. Another such change or reversal applies to the order of filling the areas of the grid that dominates the canvas. No longer does she begin from the upper right corner and then progresses to lower areas, but rather she begins “from the very spot”, she says, “that excites me the most”. Beginning the painting from an incidental spot on the canvas yields a new painterly expression: the emergence of uniform color fields looming in opaque shades of white, pink and yellow. In one of the new paintings the grid was forsaken altogether to give way to a direct, intuitive painting mode.

Already in “Dreamers”, Nachmani’s 2006 exhibition (Dvir Gallery), she collated different means of expression. These were two canvasses: the one a detailed rendering of thick vegetation, and the other a freer and looser expression of childhood memories, fantasies or dreams. She explained the antithesis by saying that the full painting, although ostensibly whole, by its tight coverage the canvas also remains out of breath; while the ostensibly emptier painting has more space and air in it. In her current works, the full and the empty, being and non-being, are joined in the same canvass as two contradicting and complementary modes: the bush – a contrasted image of multicolored, intertwined vegetation, without background or means of escape; and its opposite, the exposed surface – a return to the blank page, to the purely abstract, to the point of inception. On the relations between various types of pictorial representation and their bearing on contemporary issues we learn from an essay by Barry Schwabsky, "Painting in the Interrogative Mode". “What is contemporary painting about?” asks Schwabsky, and answers by saying that similarly to the modernist tradition, today’s painters deal not just with the practice of painting, but with the representation of an idea about painting. “That is one reason there is so little contradiction now between abstract and representational painting: In both cases, the painting is there not to represent the image; the image exists in order to represent the painting (that is, the painting’s idea of painting). The presence of this dialectic in Nachmani’s work amounts to a credo of faith in painting.

To interpret Nachmani’s paintings solely by means technical-painterly terms would be inadequate. Yet her work, although not primarily autobiographical, often presents recurrent themes drawn her close environment – the home, the backyard, her family album and childhood memories – as meaningful subjects. To her, the dimensions of a “place” make up a mental or emotional universe – just as they comprise a physical or geographic location. The current transformations in her work can therefore be assigned to a “place” by way of a primary discovery of being, and in Nachmani’s case – to her becoming a mother. Ariel Hirshfeld described this kind of place as “The womb that holds the fetus, the mother’s lap that encloses the baby, and the mother’s face that sees the child. Pertaining to Nachmani’s new paintings, the shift from expansion to reduction is equivalent to the passage from a material plenitude on to an emotional one.

Yaniv Shapira

October 2010

Place Filler

October 30th- December 11th, 2010

One autumn day of 2006, Vered Nachmani encountered a persimmon grove which was to become the subject of her forthcoming exhibition. The persimmon trees, divested of their foliage, their rotting fruit still hanging on the branches or lying at their foot, were lit by early evening sunbeams. The impression, which she briefly absorbed and has cherished since, was further intensified by the presence of a large gloomy nut tree at the rear end of the naked plantation. Several times she returned there, tying in vain to capture a similar moment with her camera. The fleeting sight she had glimpsed – a combination of sunset glows, evening shadows and rotting fruit – set itself in her memory. It is fair to say then, that in her current series of paintings she tries to reproduce this fleeting moment.

An ongoing acquaintance with the paintings of Vered Nachmani yields a number of insights pertaining to the characteristics of her work: she paints from photographs, and divides her canvas using a grid; the resulting surfaces are filled with color in a progressive manner, and the light source is given meticulous treatment – steps that are taken primarily to maintain a faithfulness to the source image. However, in recent years her paintings have loosened their grip on reality and showed a growing tendency towards expressive figuration and abstraction. If we look at the persimmons as a microcosm of Nachmani’s painting, then a reversal of priorities becomes apparent. Nachmani approaches the persimmons as in classical still-life paintings, yet she testifies to a will “to depict them with single brush-strokes, ones that enable a fresh and liberated expression that ‘gives a persimmon’ – without volume or an attempted illusionism; a persimmon more faithful to the application of color on the canvas than it is to nature”. Another such change or reversal applies to the order of filling the areas of the grid that dominates the canvas. No longer does she begin from the upper right corner and then progresses to lower areas, but rather she begins “from the very spot”, she says, “that excites me the most”. Beginning the painting from an incidental spot on the canvas yields a new painterly expression: the emergence of uniform color fields looming in opaque shades of white, pink and yellow. In one of the new paintings the grid was forsaken altogether to give way to a direct, intuitive painting mode.

Already in “Dreamers”, Nachmani’s 2006 exhibition (Dvir Gallery), she collated different means of expression. These were two canvasses: the one a detailed rendering of thick vegetation, and the other a freer and looser expression of childhood memories, fantasies or dreams. She explained the antithesis by saying that the full painting, although ostensibly whole, by its tight coverage the canvas also remains out of breath; while the ostensibly emptier painting has more space and air in it. In her current works, the full and the empty, being and non-being, are joined in the same canvass as two contradicting and complementary modes: the bush – a contrasted image of multicolored, intertwined vegetation, without background or means of escape; and its opposite, the exposed surface – a return to the blank page, to the purely abstract, to the point of inception. On the relations between various types of pictorial representation and their bearing on contemporary issues we learn from an essay by Barry Schwabsky, "Painting in the Interrogative Mode". “What is contemporary painting about?” asks Schwabsky, and answers by saying that similarly to the modernist tradition, today’s painters deal not just with the practice of painting, but with the representation of an idea about painting. “That is one reason there is so little contradiction now between abstract and representational painting: In both cases, the painting is there not to represent the image; the image exists in order to represent the painting (that is, the painting’s idea of painting). The presence of this dialectic in Nachmani’s work amounts to a credo of faith in painting.

To interpret Nachmani’s paintings solely by means technical-painterly terms would be inadequate. Yet her work, although not primarily autobiographical, often presents recurrent themes drawn her close environment – the home, the backyard, her family album and childhood memories – as meaningful subjects. To her, the dimensions of a “place” make up a mental or emotional universe – just as they comprise a physical or geographic location. The current transformations in her work can therefore be assigned to a “place” by way of a primary discovery of being, and in Nachmani’s case – to her becoming a mother. Ariel Hirshfeld described this kind of place as “The womb that holds the fetus, the mother’s lap that encloses the baby, and the mother’s face that sees the child. Pertaining to Nachmani’s new paintings, the shift from expansion to reduction is equivalent to the passage from a material plenitude on to an emotional one.

Yaniv Shapira

October 2010