Lost in the pool of shadows. Un rifiuto comprensibile.

08 Jun - 31 Aug 2019

LOST IN THE POOL OF SHADOWS. UN RIFIUTO COMPRENSIBILE.

8 June – 31 August 2019

Curated by Luca Lo Pinto

Vincenzo Agnetti, Sarah Margnetti, Cloti Ricciardi, Amelia Rosselli, Cinzia Ruggeri, Franca Sacchi, Suzanne Santoro, Roman Stanczak, Patrizia Vicinelli

The exhibition brings together figures united by artistic practices and existences that are animated by a relationship of refusal, of confrontation and at the same time by the urgency of affirming their voices within the cultural system in which they have moved or still move. Most of the works featured were produced in a particular historical moment, the beginning of the ‘70s, animated by the aspiration to give life to utopias and by a form of resistance carried out on a linguistic and personal level. These artists share an intolerance of dominant structures, an emotional fragility, a sense of not belonging, a continuous desire to question themselves, an inseparable link between their personal experience and their art.

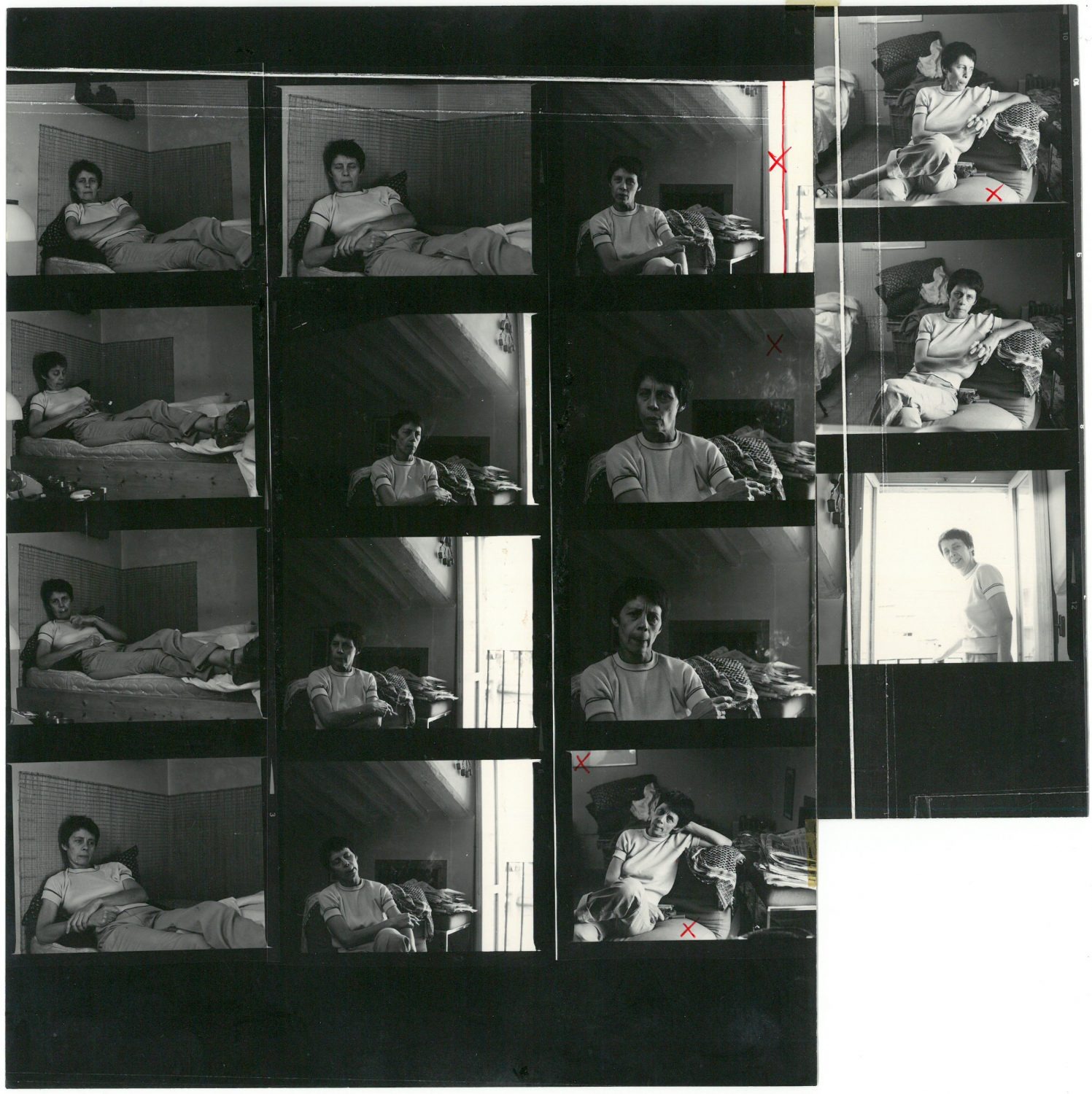

The subject of identity, the political instance, the relationship with the body are central themes in the work of Suzanne Santoro (1946) and Cloti Ricciardi (1939) with the need to redefine the female artistic subject dictated by the urgency of accessing a space – the world of art – dominated by men. Despite the fact that the feminism of the 1970s had penetrated the world of art and had fuelled a debate whose results are only now beginning to be seen, the feminist political struggle carried out by both the art world and the wider debate, although inseparable from artistic practice, has never fully identified with it.

While Vincenzo Agnetti (1926-1981) never clearly defined his political position, he did carry out an investigation into the role of language, time, communication and social criticism with great consistency. An outsider to any given movement, he often showed an ideological impatience with the artistic context in which he had taken his first steps by deciding to abandon painting in favour of a radical questioning the artwork.

Franca Sacchi (1940) was one of the very few female figures active on the Italian electronic music scene active between the late ‘60s and ‘70s, before abandoning art and experimental music to devote herself to teaching yoga, which she continues to do. Her album Ho sempre desiderato avere un cane, un gatto e un cavallo. Ora ho un gatto e un cavallo mi manca soltanto il cane (I always wanted to have a dog, a cat and a horse. Now I have a cat and a horse and I only miss the dog), published in 1973, will be the soundtrack to the exhibition.

Cinzia Ruggeri (1945) is a visionary artist and designer who in her creations combines fashion, architecture and design in a unique way that escapes any possible definition. She has experimented incessantly, pushing the language of fashion towards never before explored boundaries, designing all kinds of accessories including furniture, home interiors and theatrical sets. A surrealist imaginary that makes objects anew, making them interact with the body in an ironic and performative manner.

Roman Stanczak (1969) is a polish artist who studied at Grzegorz Kowalski’s workshop along with PaweF Althamer, Katarzyna Kozyra and Artur Zmijewski debuting on the art scene in the beginning of the ‘90s; producing a relevant and strong ensemble of works before withdrawing from the art world as soon as 1997. During these years of struggle with alcohol addiction, the artist produced a number of drawings depicting fairly-tales and a few figurative sculptures. His return was marked by the invitation of PaweF Althamer in 2013 to create a sculpture for a park in the Bródno neighbourhood of Warsaw. This year he represents Poland at the Venice Biennale.

Amelia Rosselli (1930-1996) is one of the most important voices of 20th century Italian poetry. The tragic experiences of her adolescence (the killing of her father by the fascists and various migrations between France, England, America and finally to Italy) evoked in her a sort of linguistic dissociation and a condition of permanent displacement, reflected in her use of language. Rosselli’s poetry – emotional, pained, cultured, sophisticated – represents a melee with reality that sadly ended with suicide in 1996.

In her brief and dramatic existence, Patrizia Vicinelli (1943- 1991) took part in the Italian neo-avant-garde scene by joining Gruppo 63 and collaborating with Emilio Villa in magazines such as Ex and Quindici. Vicinelli produced bold writing, situated between visual and sound poetry, with a strong performative calling, always dictated by a great intellectual force that has made her an influential figure in the underground literary and film scene. Her self-destructive nature led her to a restless existence studded with stories of drugs, prison and illness, depriving her of the recognition she deserved.

Sarah Margnetti (1983) studied at The Van der Kelen-Logelain Institute in Brussels, the longest established school in the world specialising in traditional decorative painting techniques. While there, the artist perfected the technique of trompe l’oeil, developing her own pictorial imagery combining optical illusions with abstract and surreal motifs often including parts of her body. Margnetti will conceive a wall painting for the exhibition that will also serve as an ideal backdrop for the other works on display.

– Luca Lo Pinto

A special thanks to all the artists and to Germana Agnetti, Bianca Boscu, Giuseppe Casetti, Mario Diacono, Giuseppe Garrera, Michal Lasota, Patrizio Peterlini, Massimo Piersanti, Mariolina Ricciardi.

Vincenzo Agnetti

My current works are a signal to vernacularize what I have learned, meaning my theoretical and critical research. I write things from which I derive my pictures, which in turn inspire other writings...

I think that anyone who looks at a work of this kind undergoes an act of mental violence before understanding the message; subsequently seeking to go into greater depth, to go forward and reach conclusions. And that, for me is the only way to get the visitor to continue to see the exhibition even after leaving the gallery.

Cloti Ricciardi

It was beautiful. It was a day for every artist. It happened to me on a Thursday, and Thursday was the day we had the Pompeo Magno meeting. Then I said “we’re going to do the Pompeo Magno at Palazzo Taverna!”. And so we did! Since it was a feminist meeting I made some female figures in perspex like those figures one puts outside the bathroom and I attached them to the door because it was forbidden for men to enter, in fact the exhibition was called just that: Vietato l’ingresso agli uomini (Forbidden for men to enter). We had our meeting quietly. The funny thing was that the door remained open and we witnessed the wrath of God! There was a kind of revolt from the men who wanted to enter. I was aware at the time that feminist collectives were at the avantgarde, but I lacked awareness of what it meant to bring feminism to a place dedicated to art, which does not possess a good understanding, let’s say. With hindsight, the fact that they were all women, the image of women arguing with all the men looking in from outside... the impact was incredible! The men reacted very badly and there were also many male artists who were indignant, they saw it as a presumptuous act, one of power. Not only could you not come and see why there was nothing to see, at most you stood outside and listened, but I don’t really care who was in or outside, this was outrage. It was a very powerful moment.

Amelia Rosselli

In truth, there are very close relations between my biography and my poetry, even if each of them obeys its own laws. Of course, the death of my father (and the way in which it happened) and all the consequent migrations that it obliged me to undertake have produced a sort of linguistic dissociation and a condition of permanent inconsistency. Language reflects such conditions. In fact, my concern is to effect a reconstitution, above all by setting the language of poetry to the rhythm of the laws of composition.

Cinzia Ruggeri

I love freedom and I hate prejudices, I just wanted to express myself and my ideas in a completely free environment and in different fields and make people smile.

Fashion allowed me to explore the wearer’s intimate secrets, needs and desires, but also a person’s crazes, fads and nervous disorders and I loved this aspect, as the entire point behind my work wasn’t to continuously and bulimically create, but to tackle and explore these issues through behavioural garments.

I never stopped creating for myself. Whenever I couldn’t find something that I liked, even a tablecloth, I would make it for myself, as a reaction to global and mass markets.

Franca Sacchi

At a certain point I realised that the “discourse on the evolution of musical language” not only didn’t interest me anymore, but also annoyed me. I felt it was false, forced, schizophrenic, imposed upon current ideology, from which, however, I did not have the courage to detach myself. I could no longer stand this alienated way of “making art”, this separation between art and life. I discovered, or rather, admitted that what really interested me was myself and my self development and that whatever I did towards it would automatically be reflected in my actions, in the manifestations of my existence.

Suzanne Santoro

I think, by now, that in life it is necessary to do what is necessary, not what you like to do. Before, my idea of art was simply that because I liked it, it gave me passion, it repaid me. Today, honestly, it no longer repays me as it used to. Elisabetta Rasy, a feminist and linguist writer, said something interesting, which is a theme already approached by feminists, “I work when I want to work”. That is to say, enough with this idea of the product, this idea of having to make something all the time, which is an attitude that unfortunately belongs very much to the world of art, this anxiety about producing, to be behind the galleries. Instead, Carla Lonzi says that we must re-evaluate the non- productive moments, even more so since, as women, we have been considered for centuries as non-productive in the world of culture. But there is a positive aspect to this if one considers what it is to be non-productive. It is the social, the conversation, the affection, the feeling that corresponds to life.

Roman Stanczak

I am constantly in some kind of conflict, an existential search, gazing into myself, others, for some spiritual aspect, in search of nothingness, impermanence. This theme has been with me all the time, since my childhood, non-stop. Different moral conflicts. Making different things as an experiment, checking-forgiving.

Patrizia Vicinelli

The sentence aspires to go beyond the same ideogram in its macroscopic temptation and in dying forever germinates from its semantic protoplasm a sort of staggered micro-pictorial phonemetic

in it life shouting looks for the armor (of the psyche and the page)

biography is the irrepressible necessity of my poetry if it manages as I try to identify itself more and more with research and with it to make me more and more concretely a citizen of the new city.

Sarah Margnetti

My site-specific wall paintings are usually an experience limited in time. It is aimed to disappear with the end of each exhibition. The ephemeral quality of the work can be hard for me sometimes but it emphasizes a strong and direct connection to the present. The body parts I depict in the paintings are mainly observed from my own body. When I was alone in my studio it appeared to be the most convenient form of model. What started out from the necessity of a model took the form of cryptic self-portraits. This process of self-examination and body fragmentation works also as an image for the state of deconstruction in which I find myself.

Bibliography:

Giulia Callino, “La sacralità di fare arte: la storia di Franca Sacchi”, 2016 – https://www.rockit.it/articolo/franca-sacchi- storia-improvvisazione-musica-enstatica-yoga

Marta Seravalli, “Arte e Femminismo a Roma negli anni ’70”, Biblink editori, 2013

Amelia Rosselli, “E’ vostra la vita che ho perso – Conversazioni e interviste 1964-1995”, Le Lettere, 2011

Anna Battista, “The Quirky Aesthetics of Joy: Interview with Cinzia Ruggeri”, 2013 – https://irenebrination.typepad.com/ irenebrination_notes_on_a/2013/05/cinzia-ruggeri-interview.html

Roman Stanczak, “Life and Work”, NERO Editions, 2016

Mario Perazzi, “Non dipingo i miei quadri. Intervista con Vincenzo Agnetti”, Corriere della Sera, 20.2.1972

8 June – 31 August 2019

Curated by Luca Lo Pinto

Vincenzo Agnetti, Sarah Margnetti, Cloti Ricciardi, Amelia Rosselli, Cinzia Ruggeri, Franca Sacchi, Suzanne Santoro, Roman Stanczak, Patrizia Vicinelli

The exhibition brings together figures united by artistic practices and existences that are animated by a relationship of refusal, of confrontation and at the same time by the urgency of affirming their voices within the cultural system in which they have moved or still move. Most of the works featured were produced in a particular historical moment, the beginning of the ‘70s, animated by the aspiration to give life to utopias and by a form of resistance carried out on a linguistic and personal level. These artists share an intolerance of dominant structures, an emotional fragility, a sense of not belonging, a continuous desire to question themselves, an inseparable link between their personal experience and their art.

The subject of identity, the political instance, the relationship with the body are central themes in the work of Suzanne Santoro (1946) and Cloti Ricciardi (1939) with the need to redefine the female artistic subject dictated by the urgency of accessing a space – the world of art – dominated by men. Despite the fact that the feminism of the 1970s had penetrated the world of art and had fuelled a debate whose results are only now beginning to be seen, the feminist political struggle carried out by both the art world and the wider debate, although inseparable from artistic practice, has never fully identified with it.

While Vincenzo Agnetti (1926-1981) never clearly defined his political position, he did carry out an investigation into the role of language, time, communication and social criticism with great consistency. An outsider to any given movement, he often showed an ideological impatience with the artistic context in which he had taken his first steps by deciding to abandon painting in favour of a radical questioning the artwork.

Franca Sacchi (1940) was one of the very few female figures active on the Italian electronic music scene active between the late ‘60s and ‘70s, before abandoning art and experimental music to devote herself to teaching yoga, which she continues to do. Her album Ho sempre desiderato avere un cane, un gatto e un cavallo. Ora ho un gatto e un cavallo mi manca soltanto il cane (I always wanted to have a dog, a cat and a horse. Now I have a cat and a horse and I only miss the dog), published in 1973, will be the soundtrack to the exhibition.

Cinzia Ruggeri (1945) is a visionary artist and designer who in her creations combines fashion, architecture and design in a unique way that escapes any possible definition. She has experimented incessantly, pushing the language of fashion towards never before explored boundaries, designing all kinds of accessories including furniture, home interiors and theatrical sets. A surrealist imaginary that makes objects anew, making them interact with the body in an ironic and performative manner.

Roman Stanczak (1969) is a polish artist who studied at Grzegorz Kowalski’s workshop along with PaweF Althamer, Katarzyna Kozyra and Artur Zmijewski debuting on the art scene in the beginning of the ‘90s; producing a relevant and strong ensemble of works before withdrawing from the art world as soon as 1997. During these years of struggle with alcohol addiction, the artist produced a number of drawings depicting fairly-tales and a few figurative sculptures. His return was marked by the invitation of PaweF Althamer in 2013 to create a sculpture for a park in the Bródno neighbourhood of Warsaw. This year he represents Poland at the Venice Biennale.

Amelia Rosselli (1930-1996) is one of the most important voices of 20th century Italian poetry. The tragic experiences of her adolescence (the killing of her father by the fascists and various migrations between France, England, America and finally to Italy) evoked in her a sort of linguistic dissociation and a condition of permanent displacement, reflected in her use of language. Rosselli’s poetry – emotional, pained, cultured, sophisticated – represents a melee with reality that sadly ended with suicide in 1996.

In her brief and dramatic existence, Patrizia Vicinelli (1943- 1991) took part in the Italian neo-avant-garde scene by joining Gruppo 63 and collaborating with Emilio Villa in magazines such as Ex and Quindici. Vicinelli produced bold writing, situated between visual and sound poetry, with a strong performative calling, always dictated by a great intellectual force that has made her an influential figure in the underground literary and film scene. Her self-destructive nature led her to a restless existence studded with stories of drugs, prison and illness, depriving her of the recognition she deserved.

Sarah Margnetti (1983) studied at The Van der Kelen-Logelain Institute in Brussels, the longest established school in the world specialising in traditional decorative painting techniques. While there, the artist perfected the technique of trompe l’oeil, developing her own pictorial imagery combining optical illusions with abstract and surreal motifs often including parts of her body. Margnetti will conceive a wall painting for the exhibition that will also serve as an ideal backdrop for the other works on display.

– Luca Lo Pinto

A special thanks to all the artists and to Germana Agnetti, Bianca Boscu, Giuseppe Casetti, Mario Diacono, Giuseppe Garrera, Michal Lasota, Patrizio Peterlini, Massimo Piersanti, Mariolina Ricciardi.

Vincenzo Agnetti

My current works are a signal to vernacularize what I have learned, meaning my theoretical and critical research. I write things from which I derive my pictures, which in turn inspire other writings...

I think that anyone who looks at a work of this kind undergoes an act of mental violence before understanding the message; subsequently seeking to go into greater depth, to go forward and reach conclusions. And that, for me is the only way to get the visitor to continue to see the exhibition even after leaving the gallery.

Cloti Ricciardi

It was beautiful. It was a day for every artist. It happened to me on a Thursday, and Thursday was the day we had the Pompeo Magno meeting. Then I said “we’re going to do the Pompeo Magno at Palazzo Taverna!”. And so we did! Since it was a feminist meeting I made some female figures in perspex like those figures one puts outside the bathroom and I attached them to the door because it was forbidden for men to enter, in fact the exhibition was called just that: Vietato l’ingresso agli uomini (Forbidden for men to enter). We had our meeting quietly. The funny thing was that the door remained open and we witnessed the wrath of God! There was a kind of revolt from the men who wanted to enter. I was aware at the time that feminist collectives were at the avantgarde, but I lacked awareness of what it meant to bring feminism to a place dedicated to art, which does not possess a good understanding, let’s say. With hindsight, the fact that they were all women, the image of women arguing with all the men looking in from outside... the impact was incredible! The men reacted very badly and there were also many male artists who were indignant, they saw it as a presumptuous act, one of power. Not only could you not come and see why there was nothing to see, at most you stood outside and listened, but I don’t really care who was in or outside, this was outrage. It was a very powerful moment.

Amelia Rosselli

In truth, there are very close relations between my biography and my poetry, even if each of them obeys its own laws. Of course, the death of my father (and the way in which it happened) and all the consequent migrations that it obliged me to undertake have produced a sort of linguistic dissociation and a condition of permanent inconsistency. Language reflects such conditions. In fact, my concern is to effect a reconstitution, above all by setting the language of poetry to the rhythm of the laws of composition.

Cinzia Ruggeri

I love freedom and I hate prejudices, I just wanted to express myself and my ideas in a completely free environment and in different fields and make people smile.

Fashion allowed me to explore the wearer’s intimate secrets, needs and desires, but also a person’s crazes, fads and nervous disorders and I loved this aspect, as the entire point behind my work wasn’t to continuously and bulimically create, but to tackle and explore these issues through behavioural garments.

I never stopped creating for myself. Whenever I couldn’t find something that I liked, even a tablecloth, I would make it for myself, as a reaction to global and mass markets.

Franca Sacchi

At a certain point I realised that the “discourse on the evolution of musical language” not only didn’t interest me anymore, but also annoyed me. I felt it was false, forced, schizophrenic, imposed upon current ideology, from which, however, I did not have the courage to detach myself. I could no longer stand this alienated way of “making art”, this separation between art and life. I discovered, or rather, admitted that what really interested me was myself and my self development and that whatever I did towards it would automatically be reflected in my actions, in the manifestations of my existence.

Suzanne Santoro

I think, by now, that in life it is necessary to do what is necessary, not what you like to do. Before, my idea of art was simply that because I liked it, it gave me passion, it repaid me. Today, honestly, it no longer repays me as it used to. Elisabetta Rasy, a feminist and linguist writer, said something interesting, which is a theme already approached by feminists, “I work when I want to work”. That is to say, enough with this idea of the product, this idea of having to make something all the time, which is an attitude that unfortunately belongs very much to the world of art, this anxiety about producing, to be behind the galleries. Instead, Carla Lonzi says that we must re-evaluate the non- productive moments, even more so since, as women, we have been considered for centuries as non-productive in the world of culture. But there is a positive aspect to this if one considers what it is to be non-productive. It is the social, the conversation, the affection, the feeling that corresponds to life.

Roman Stanczak

I am constantly in some kind of conflict, an existential search, gazing into myself, others, for some spiritual aspect, in search of nothingness, impermanence. This theme has been with me all the time, since my childhood, non-stop. Different moral conflicts. Making different things as an experiment, checking-forgiving.

Patrizia Vicinelli

The sentence aspires to go beyond the same ideogram in its macroscopic temptation and in dying forever germinates from its semantic protoplasm a sort of staggered micro-pictorial phonemetic

in it life shouting looks for the armor (of the psyche and the page)

biography is the irrepressible necessity of my poetry if it manages as I try to identify itself more and more with research and with it to make me more and more concretely a citizen of the new city.

Sarah Margnetti

My site-specific wall paintings are usually an experience limited in time. It is aimed to disappear with the end of each exhibition. The ephemeral quality of the work can be hard for me sometimes but it emphasizes a strong and direct connection to the present. The body parts I depict in the paintings are mainly observed from my own body. When I was alone in my studio it appeared to be the most convenient form of model. What started out from the necessity of a model took the form of cryptic self-portraits. This process of self-examination and body fragmentation works also as an image for the state of deconstruction in which I find myself.

Bibliography:

Giulia Callino, “La sacralità di fare arte: la storia di Franca Sacchi”, 2016 – https://www.rockit.it/articolo/franca-sacchi- storia-improvvisazione-musica-enstatica-yoga

Marta Seravalli, “Arte e Femminismo a Roma negli anni ’70”, Biblink editori, 2013

Amelia Rosselli, “E’ vostra la vita che ho perso – Conversazioni e interviste 1964-1995”, Le Lettere, 2011

Anna Battista, “The Quirky Aesthetics of Joy: Interview with Cinzia Ruggeri”, 2013 – https://irenebrination.typepad.com/ irenebrination_notes_on_a/2013/05/cinzia-ruggeri-interview.html

Roman Stanczak, “Life and Work”, NERO Editions, 2016

Mario Perazzi, “Non dipingo i miei quadri. Intervista con Vincenzo Agnetti”, Corriere della Sera, 20.2.1972