Sean Landers

13 Nov - 20 Dec 2014

© Sean Landers

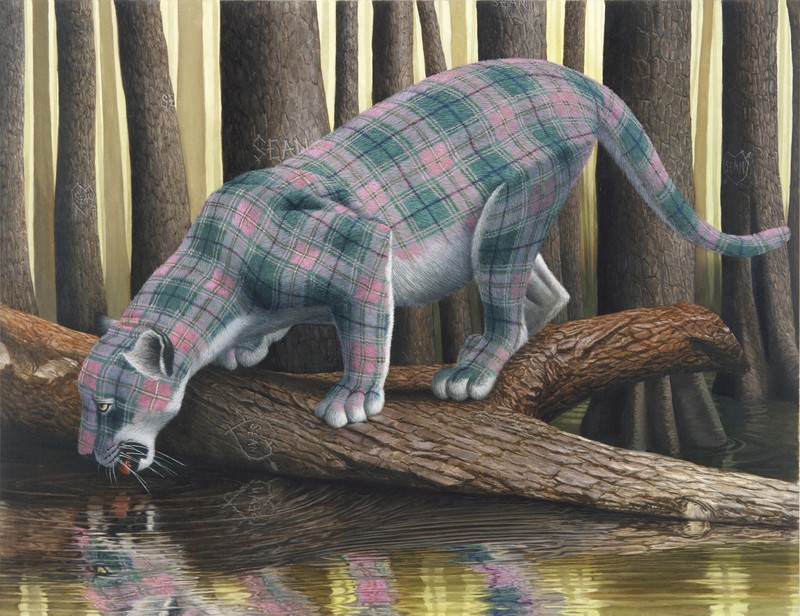

The Urgent Necessity of Narcissism for the Artistic Mind (Jaguar), 2014

Oil on linen

50 x 65 inches

The Urgent Necessity of Narcissism for the Artistic Mind (Jaguar), 2014

Oil on linen

50 x 65 inches

SEAN LANDERS

North American Mammals

13 November - 20 December 2014

Petzel Gallery is pleased to announce a new exhibition of paintings by Sean Landers. This will be the gallery’s third solo show with the New York based artist.

Sean Landers’s newest body of work depicts a layered story of mortality, artistic legacy, and the posterity of art. Since the 1990s Landers has produced a diverse body of paintings, sculptures, drawings, and videos that, regardless of form or style, bares the artist to the world. From stream-of-consciousness text paintings, videos, and a novel to representational narrative paintings to his abstracted and fragmented text works, Landers has used the relationship between verbal and visual language to strip the sacrosanct myths associated with art and artist while simultaneously constructing new ones in his own likeness. This exhibition continues the practice of exploring the meaning of what it is to be a contemporary maker of art and poses questions beyond the quotidian of the studio.

The exhibition “North American Mammals” is divided into three groups of paintings, each of which spiderweb in reference to one another. The first group is comprised of nine paintings depicting steel gray library bookshelves holding neatly stacked books. Each of the tightly painted book spines directs their vertically embossed titles out to the viewer. The titles have the surreal ability to disassociate themselves from the painted image, as if to float beyond their representational bounds. As the titles are read from left to right, they complete each chapter of Landers’s prose. Rather than the artist’s well-known Joycean stream-of-consciousness writing, the new work ruminates with an existential voice. Themes run from the eternal existence of a painting [Mountain Goat (An Argument for Solipsism) and Boar (Brueghel the Archer)] to collecting and being collected [Howler Monkey (Casting it Back Out to Sea) and Hare (The Promiscuity of Art)] to the core attributes of being an artist [Jaguar (The Urgent Necessity of Narcissism for the Artistic Mind) and Pony (When Performance Becomes Reality)]. Further, Landers associates new symbols with every story in the form of an animal: bear, hare, boar, horse, goat, monkey, jaguar, coyote, and fawn. In each painting the symbol appears twice—once as the title of the first book upon the shelf and later as visions of the animals in their natural habitats as seen through a crystal ball poised upon a shelf below.

The globe’s prescient vision leads us to a group of paintings where Landers’s symbols reappear transformed in a variety of Scottish tartan designs. In the library painting Fawn (Strange Progeny), 2014, Landers writes, “These tartan animals represent the first time that I ever thought of my paintings in such a deliberate parent-like fashion. I have cloaked them in tartan fur to help protect them from indifference on their journey through time.” The narcissist jaguar now glows in pink and green and Black Bear and Cardinal (Sincerity and Empathy)’s black bear is dressed up in deep ultramarine blue. These recall Landers’s earlier paintings, such as Tartan Buck, 2005, yet the pattern nods to Landers’s renewed interest in René Magritte’s 1947–48 “vache” period—a series that marked a radical departure from Magritte’s cool, detached, Surrealist style to an intentionally more caricatured one, identified by Bernard Marcadé as “freedom from aesthetic and moral injunctions and prescriptions.” Homages to the Belgian surrealist have appeared in previous Landers paintings, The Idea Man and Three Nose Guy (painted in 1998 and 1999, respectively), and continue beyond the multicolored tartans as the artist fits his patterned coyote in Proximate Strangers (Coyote and Crow), 2014, with Magritte’s famous pipe from the painting The Treachery of Images, 1929.

Much like Magritte, Landers’s paintings often negotiate the visual relationships between image and word. In the library paintings, the book titles willfully detach themselves from their associated images to operate as prose. Landers’s tartan patterns contain a visual metonymic phrase of “to coat.” The phrase can be used as to “apply a coat of paint” as much as it refers to the natural fur of an animal. Thus, through the hand of the artist, each animal receives a freshly painted coat of fur. Landers often creates symbols to encompass certain attributes, such as an image of a fawn to stand in for progeny or a mountain goat for solipsism. In other works, a symbol can relate to an entire novel that, in turn, can stand in as a larger metaphor for artistic ambition.

The environment in the exhibition’s last series changes from land to sea. A twenty- eight-foot-long tartan sperm whale painting, Moby Dick (Merrilees), 2013, dominates a room filled with a graveyard of ships sunk upon the ocean’s floor. Moby Dick (Merrilees) references the famed novel by Herman Melville, published in 1851, recounting Captain Ahab’s monomaniacal search for the elusive white whale. Landers, long fascinated by this epic novel, strongly identifies with Captain Ahab’s single-minded pursuit—arguably a metaphor for the pursuit of greatness and immortality, or, in the case of a visual artist, a place in the art-historical canon. The harpoons and trailing ropes that scar the red-and-blue whale’s body are symbols of Landers’s attempt to make a lasting work of art. The tattered whale eludes the determined artist, emphasizing the immensity of the struggle by violently diving just below the murky water’s surface.

The Melville novel is an apt analogy for Landers’s work. The 133-chapter book uses a diverse range of literary devices (songs, poetry, catalogues, Shakespearean stage directions, soliloquies, and asides) to tell one story. Likewise, Landers’s series and styles have been just as divergent. This has been proven true with painting metaphors pertaining to the sea, from a voyage gone awry in Sea[sic], 1995, to Alone, 1996, to his 2011 exhibition “Around the World Alone”—twelve oil paintings that depict a solo-circumnavigating sailor-clown on his life-long voyage. For Landers the ocean signifies stream-of-consciousness, the sailor as a life journey, and Moby Dick the object of artistic pursuit. The sunken ship on the ocean’s floor, on the other hand, can signify the sunken dreams of the journey’s end. Landers’s epilogue is written in stone-ruin epitaphs littered upon the seabed.

Questions of mortality haunt these paintings as much as the speculation of artistic immortality echoes throughout the paintings of the libraries. Inspiration is the binding between the two. Again, Landers’s paintings emphasize the word’s double meaning. What happens when you stop breathing? You cease to inspire, especially when submerged. Yet the beauty of artistic inspiration—whether from the effect of Landers’s own paintings or from those he champions, from Patinir and Brueghel to Magritte and Melville—is that it spiritually transports both artist and audience beyond their earthly bounds.

His work has been exhibited in numerous solo exhibitions, including the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (2010) and the Kunsthalle Zurich (2004) and many group exhibitions including “Aquatopia: The Imaginary of the Ocean Deep,” Tate St. Ives, UK (2014), “NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star,” New Museum, NY (2013), “Drawing Time, Reading Time, the Drawing Center, New York NY (2013), “Busted,” the High Line, New York, NY (2013-2014), “Midnight Party,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN (2011).. His paintings will be included in the forthcoming exhibition “Picasso in Contemporary Art” at Deichtorhallen Hamburg in spring 2015.

North American Mammals

13 November - 20 December 2014

Petzel Gallery is pleased to announce a new exhibition of paintings by Sean Landers. This will be the gallery’s third solo show with the New York based artist.

Sean Landers’s newest body of work depicts a layered story of mortality, artistic legacy, and the posterity of art. Since the 1990s Landers has produced a diverse body of paintings, sculptures, drawings, and videos that, regardless of form or style, bares the artist to the world. From stream-of-consciousness text paintings, videos, and a novel to representational narrative paintings to his abstracted and fragmented text works, Landers has used the relationship between verbal and visual language to strip the sacrosanct myths associated with art and artist while simultaneously constructing new ones in his own likeness. This exhibition continues the practice of exploring the meaning of what it is to be a contemporary maker of art and poses questions beyond the quotidian of the studio.

The exhibition “North American Mammals” is divided into three groups of paintings, each of which spiderweb in reference to one another. The first group is comprised of nine paintings depicting steel gray library bookshelves holding neatly stacked books. Each of the tightly painted book spines directs their vertically embossed titles out to the viewer. The titles have the surreal ability to disassociate themselves from the painted image, as if to float beyond their representational bounds. As the titles are read from left to right, they complete each chapter of Landers’s prose. Rather than the artist’s well-known Joycean stream-of-consciousness writing, the new work ruminates with an existential voice. Themes run from the eternal existence of a painting [Mountain Goat (An Argument for Solipsism) and Boar (Brueghel the Archer)] to collecting and being collected [Howler Monkey (Casting it Back Out to Sea) and Hare (The Promiscuity of Art)] to the core attributes of being an artist [Jaguar (The Urgent Necessity of Narcissism for the Artistic Mind) and Pony (When Performance Becomes Reality)]. Further, Landers associates new symbols with every story in the form of an animal: bear, hare, boar, horse, goat, monkey, jaguar, coyote, and fawn. In each painting the symbol appears twice—once as the title of the first book upon the shelf and later as visions of the animals in their natural habitats as seen through a crystal ball poised upon a shelf below.

The globe’s prescient vision leads us to a group of paintings where Landers’s symbols reappear transformed in a variety of Scottish tartan designs. In the library painting Fawn (Strange Progeny), 2014, Landers writes, “These tartan animals represent the first time that I ever thought of my paintings in such a deliberate parent-like fashion. I have cloaked them in tartan fur to help protect them from indifference on their journey through time.” The narcissist jaguar now glows in pink and green and Black Bear and Cardinal (Sincerity and Empathy)’s black bear is dressed up in deep ultramarine blue. These recall Landers’s earlier paintings, such as Tartan Buck, 2005, yet the pattern nods to Landers’s renewed interest in René Magritte’s 1947–48 “vache” period—a series that marked a radical departure from Magritte’s cool, detached, Surrealist style to an intentionally more caricatured one, identified by Bernard Marcadé as “freedom from aesthetic and moral injunctions and prescriptions.” Homages to the Belgian surrealist have appeared in previous Landers paintings, The Idea Man and Three Nose Guy (painted in 1998 and 1999, respectively), and continue beyond the multicolored tartans as the artist fits his patterned coyote in Proximate Strangers (Coyote and Crow), 2014, with Magritte’s famous pipe from the painting The Treachery of Images, 1929.

Much like Magritte, Landers’s paintings often negotiate the visual relationships between image and word. In the library paintings, the book titles willfully detach themselves from their associated images to operate as prose. Landers’s tartan patterns contain a visual metonymic phrase of “to coat.” The phrase can be used as to “apply a coat of paint” as much as it refers to the natural fur of an animal. Thus, through the hand of the artist, each animal receives a freshly painted coat of fur. Landers often creates symbols to encompass certain attributes, such as an image of a fawn to stand in for progeny or a mountain goat for solipsism. In other works, a symbol can relate to an entire novel that, in turn, can stand in as a larger metaphor for artistic ambition.

The environment in the exhibition’s last series changes from land to sea. A twenty- eight-foot-long tartan sperm whale painting, Moby Dick (Merrilees), 2013, dominates a room filled with a graveyard of ships sunk upon the ocean’s floor. Moby Dick (Merrilees) references the famed novel by Herman Melville, published in 1851, recounting Captain Ahab’s monomaniacal search for the elusive white whale. Landers, long fascinated by this epic novel, strongly identifies with Captain Ahab’s single-minded pursuit—arguably a metaphor for the pursuit of greatness and immortality, or, in the case of a visual artist, a place in the art-historical canon. The harpoons and trailing ropes that scar the red-and-blue whale’s body are symbols of Landers’s attempt to make a lasting work of art. The tattered whale eludes the determined artist, emphasizing the immensity of the struggle by violently diving just below the murky water’s surface.

The Melville novel is an apt analogy for Landers’s work. The 133-chapter book uses a diverse range of literary devices (songs, poetry, catalogues, Shakespearean stage directions, soliloquies, and asides) to tell one story. Likewise, Landers’s series and styles have been just as divergent. This has been proven true with painting metaphors pertaining to the sea, from a voyage gone awry in Sea[sic], 1995, to Alone, 1996, to his 2011 exhibition “Around the World Alone”—twelve oil paintings that depict a solo-circumnavigating sailor-clown on his life-long voyage. For Landers the ocean signifies stream-of-consciousness, the sailor as a life journey, and Moby Dick the object of artistic pursuit. The sunken ship on the ocean’s floor, on the other hand, can signify the sunken dreams of the journey’s end. Landers’s epilogue is written in stone-ruin epitaphs littered upon the seabed.

Questions of mortality haunt these paintings as much as the speculation of artistic immortality echoes throughout the paintings of the libraries. Inspiration is the binding between the two. Again, Landers’s paintings emphasize the word’s double meaning. What happens when you stop breathing? You cease to inspire, especially when submerged. Yet the beauty of artistic inspiration—whether from the effect of Landers’s own paintings or from those he champions, from Patinir and Brueghel to Magritte and Melville—is that it spiritually transports both artist and audience beyond their earthly bounds.

His work has been exhibited in numerous solo exhibitions, including the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (2010) and the Kunsthalle Zurich (2004) and many group exhibitions including “Aquatopia: The Imaginary of the Ocean Deep,” Tate St. Ives, UK (2014), “NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star,” New Museum, NY (2013), “Drawing Time, Reading Time, the Drawing Center, New York NY (2013), “Busted,” the High Line, New York, NY (2013-2014), “Midnight Party,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN (2011).. His paintings will be included in the forthcoming exhibition “Picasso in Contemporary Art” at Deichtorhallen Hamburg in spring 2015.