Vedovamazzei

17 Nov - 30 Dec 2012

VEDOVAMAZZEI

No necesitas suerte

17 November - 30 December 2012

Fúcares Gallery presents the second solo show by Vedovamazzei (Milan, Simeone Crispino, 1964 y Stella Scala, 1962) in Spain.

VEDOVAMAZZEI or “The art of widowhood”

It is not a common thing for someone to be forced to be widowed. Yet this is what Estella Scala (1964) and Simeone Crispino (1962) did. Their artistic collaboration which began in 1991 was an association beyond the personalities of both, and also bound to survive their sentimental breakup. Widowhood made it compulsory to accept death with more than reasonable dignity and not let oneself go, for this widow should be a merry one.

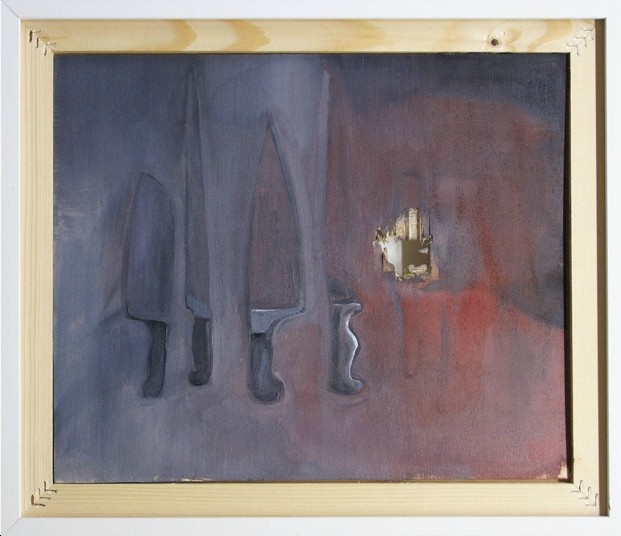

To start with, their partnership thus falls within the contemporary art practice of manipulating signs so as to give shape to an open – not fictitious – reality, but one open to a field endlessly enlarged by semantic experiences. They chose to mix processes up, to multiply expressive procedures, explore inventive possibilities rejecting all forms of hierarchy. Their guiding principle seeks to look beyond appearances, to elucidate the iconographic origin and the symbolic value of objects. The absurd, so often entailed by this conduct, encourages thinking on art and its formal and intellectual postulates.

The “Vedovamazzei” patronymic opens up a space of artistic and political demands. First and foremost, it avoids biographical contingency and sociological oppressiveness: who makes what, when, where, with what credentials and what presumed limitations? Together, they build, they compose their subjectivity by themselves, confront desires, constantly question their own undertakings without being accountable to anybody, freely creating new possible spaces for themselves.

The “Mazzei Widow” is a multiple negation of identity. More than likely it is a woman from the South of Italy, possibly Naples. She lost her maiden name and then her husband. Discreetly immersed into the scrutinised realm of living shadows, dressed in black, she gives herself over to solitude. Through such loss, the identity of artists dissolves in the bonfire of the vanities. Therefore, she depends on nobody but herself and is free to discover a renewed vitality as she stands by the tomb. Mourning makes the Vedovamazzei couple appear to be a three-headed being.

Mazzei “widowhood” stages death over and over again. The identity of the artists lies in a dark zone – a descent into the abyss is always followed by a baptismal return to the light. The couple organises their funeral rites in each work, starting from scratch every time. This fresh-start attitude which is the essence of all games forestalls relaxing, doing “anything whatsoever”, but on the contrary, it invites the verification of it all – every gesture, thought, undertaking, so that each rebirth is more intense than the last.

Being widowed, in theory, makes one vulnerable, prone to being hurt, wounded. It inspires respect, gives rise to compassion and sympathy, and opens a fissure. Here, fragility is not due to unfulfillment, but to the heavy burden of accumulated meaning. It is just from this standpoint that the Vedovamazzei try to understand subjectivity, which is the central topic of their polymorphic and ambiguous work. Why go, and how to go, from a fixed identity – from the violence imposed both on the living and on society – to a humorous, intelligent and liberating work?

Vedovamazzei show that subjectivity is no way a supreme act of awareness that eludes one’s constraints but is subjected to the Other’s authoritarian regime. Recognition leads to the reification of the self. In our most immediate surroundings, coming across the Other’s true face is absolutely impossible. Subjectivity is literally altered. The Other is limited to showing us our own face, as they expect from us. The face in their latest paintings is bruised, devastated. Who is the Other? It is often just the title that tells us of their presence. And the identity attached to this paradox consists of subjecting the face to relentless destruction. [“Putin, 2011; A Smart Study about Bush’s Family, 2011, Esperienza Morale (A Terrible Beauty is Born) Colt 2011...”]. The name seems to give rise to an appropriation while it radically vanishes. We are at odds with the notion of a portrait, the suitability of a name, a face and a person. Suddenly, I no longer have before me an object that I know or possess, but the presence of what I reject. This destruction makes true subjectivity emerge as a consequence of undermining imposed models of representation.

In this sense, the living is similar to the social. Vedovamazzei’s works are about transformations, exchanges, metamorphosis, changes in material conditions. They constitute a spectacle about life from the viewpoint of death, decrepitude and disintegration. Italian widows, who cluster in churches, know that “if the grain of wheat does not die...”. The process of transforming materials nourished by death is the mechanism needed for any creative act. Why adhere to imposed limits? Ashes become a pictorial substance, saliva soaking cigarette paper [“1933”, 2011] is at the origins of a monochromatic painting... All these elements confirm the notion of art-making as a constant process of manipulation. A small, single gesture, or a slight exageration is sometimes enough. The works are fraught with several possible reifications: it is enough to freeze the moments of the permanent cycle to suggest that each death is an opportunity for new life.

Some pieces are characterised by their twisted, shattered nature, suddenly torn from the street. Some fragments, taken straight from the outside world, appear as memories. [Cambiare la propria mente è facile se cambi prima l’altezza, 2011; Dew Drops (Frammento di opera d’arte rinvenuta durante la mostra Over the Edge a Gent nell’anno 2000) 2011].

Their current exhibition immobilises their shifting reality and breaks their chronology. The intent is to show the fragility of our own present, the impossibility of keeping it or, simply, of sparing it from the archeology of the future. Artistic order is reversed. It is not art that should be protected or restored in our temples–museums any more. The priority here is preserving reality and our daily experiences through art. The essence of reality is its fragility and is rendered visible by its broken expressions. Wasn’t it arrogant of artists to proclaim themselves interpreters of the world, by imprisoning it in the useless shackles of transitory parameters? Yes, look shrewdly at reality, but with the distance and the gap its own nature imposes and above all, by paying attention to the way we look at things.

In Vedovamazzei there is widespread disappointment that entails a certain will to break with the commercial system of lists of artists and consumer works. An “offside” attitude that makes sure the rules of others are not neglected. The traditional notion that someone who is self-aware might take hold of the world through art is questioned, while art might in turn be transmitted by a property deed. The point is to wonder about such a twofold illusion, whose denunciation dates back to Dada, but is far from extinct. The Dadaist affinity explains that the work consists largely of a ready-made collection that comes from very diverse realms: the deceased father’s jacket [Father, 2010/2011] whose pockets have not even been emptied yet, bathroom towels, telephone numbers [WIRELESS, 2008], mattresses... [DDR/My Weakness, 2000/2012]. Vedovamazzei is in itself ready-made: the name was found on a tombstone in an Italian cemetery.

The surface of reality often presents itself to our Widow as a fragment pulled out and torn and, sometimes, under a ready-made guise. The loan of these various objects is, for a start, an act of frankness: immediate reality is pronounced as such. But their shift unleashes the clauses of the tacit contract that binds all artists to truth. The material already engenders an unprecedented production. Vedovamazzei reproduces exact fragments of everyday life (a concrete slab); envelopes [The Last Italian Envelope 1, 2009, Dew Drops-2000, We Need Imperfections to Be Imperfect, 1, 2010] turned into wood; garden [Go Wherever You Want, Bring Me Whatever You Wish, 2000-...]. Just this sole forgery is enough to restore the power of imbuing affection and singularity into what was nothing but banality or indifference.

The little intimate paintings of flowers [DEL VECCHIO GEORGE (fiori) 2010] or of geometrical motifs [CLISBY WILLIE, 2010] possess in themselves a decorative quality able to seduce. But then, why return to these post-war topics? Reifying a modernist ambition to become old-fashioned? To play with the clichés of post-modernism and their rules of repetition? Or rather to infiltrate secret signs into devices that would be devoid of meaning in their absence?

Sometimes, the point is to detect shameful and untold things about our controlled societies. Beautiful, charming motifs hand in hand with accounts of capital punishment. The body is absent from the electric chair, but its subjective rediscovery is demanded by this small sedimentation, more effective than a cry. A change occurs inside this miniscule grey layer, like a particle that becomes alive. It is more convincing than a speech intended to shame our democratic institutions. This way, hardly visible and working underground, is how Vedovamazzei master a work that restores the ability of our consciousness to assume responsibilities.

The extreme cult of gesture in no way diminishes their commitment or alertness. It is better to dream and discreetly proceed to dream again than to whine or give oneself airs. A widow knows a lot about orphans. She knows that it is useless to only touch upon misery. She would rather remember that everybody is vulnerable – her, them, us, and the powerful, too. She would rather work on the way we look at things. The Other is like us, always us, despite appearances or because of them. To help the Other, and ourselves as well, we start by offering her our respect. Here it is what the Widow shows us with dignity.

Natacha Carron Vullierme

No necesitas suerte

17 November - 30 December 2012

Fúcares Gallery presents the second solo show by Vedovamazzei (Milan, Simeone Crispino, 1964 y Stella Scala, 1962) in Spain.

VEDOVAMAZZEI or “The art of widowhood”

It is not a common thing for someone to be forced to be widowed. Yet this is what Estella Scala (1964) and Simeone Crispino (1962) did. Their artistic collaboration which began in 1991 was an association beyond the personalities of both, and also bound to survive their sentimental breakup. Widowhood made it compulsory to accept death with more than reasonable dignity and not let oneself go, for this widow should be a merry one.

To start with, their partnership thus falls within the contemporary art practice of manipulating signs so as to give shape to an open – not fictitious – reality, but one open to a field endlessly enlarged by semantic experiences. They chose to mix processes up, to multiply expressive procedures, explore inventive possibilities rejecting all forms of hierarchy. Their guiding principle seeks to look beyond appearances, to elucidate the iconographic origin and the symbolic value of objects. The absurd, so often entailed by this conduct, encourages thinking on art and its formal and intellectual postulates.

The “Vedovamazzei” patronymic opens up a space of artistic and political demands. First and foremost, it avoids biographical contingency and sociological oppressiveness: who makes what, when, where, with what credentials and what presumed limitations? Together, they build, they compose their subjectivity by themselves, confront desires, constantly question their own undertakings without being accountable to anybody, freely creating new possible spaces for themselves.

The “Mazzei Widow” is a multiple negation of identity. More than likely it is a woman from the South of Italy, possibly Naples. She lost her maiden name and then her husband. Discreetly immersed into the scrutinised realm of living shadows, dressed in black, she gives herself over to solitude. Through such loss, the identity of artists dissolves in the bonfire of the vanities. Therefore, she depends on nobody but herself and is free to discover a renewed vitality as she stands by the tomb. Mourning makes the Vedovamazzei couple appear to be a three-headed being.

Mazzei “widowhood” stages death over and over again. The identity of the artists lies in a dark zone – a descent into the abyss is always followed by a baptismal return to the light. The couple organises their funeral rites in each work, starting from scratch every time. This fresh-start attitude which is the essence of all games forestalls relaxing, doing “anything whatsoever”, but on the contrary, it invites the verification of it all – every gesture, thought, undertaking, so that each rebirth is more intense than the last.

Being widowed, in theory, makes one vulnerable, prone to being hurt, wounded. It inspires respect, gives rise to compassion and sympathy, and opens a fissure. Here, fragility is not due to unfulfillment, but to the heavy burden of accumulated meaning. It is just from this standpoint that the Vedovamazzei try to understand subjectivity, which is the central topic of their polymorphic and ambiguous work. Why go, and how to go, from a fixed identity – from the violence imposed both on the living and on society – to a humorous, intelligent and liberating work?

Vedovamazzei show that subjectivity is no way a supreme act of awareness that eludes one’s constraints but is subjected to the Other’s authoritarian regime. Recognition leads to the reification of the self. In our most immediate surroundings, coming across the Other’s true face is absolutely impossible. Subjectivity is literally altered. The Other is limited to showing us our own face, as they expect from us. The face in their latest paintings is bruised, devastated. Who is the Other? It is often just the title that tells us of their presence. And the identity attached to this paradox consists of subjecting the face to relentless destruction. [“Putin, 2011; A Smart Study about Bush’s Family, 2011, Esperienza Morale (A Terrible Beauty is Born) Colt 2011...”]. The name seems to give rise to an appropriation while it radically vanishes. We are at odds with the notion of a portrait, the suitability of a name, a face and a person. Suddenly, I no longer have before me an object that I know or possess, but the presence of what I reject. This destruction makes true subjectivity emerge as a consequence of undermining imposed models of representation.

In this sense, the living is similar to the social. Vedovamazzei’s works are about transformations, exchanges, metamorphosis, changes in material conditions. They constitute a spectacle about life from the viewpoint of death, decrepitude and disintegration. Italian widows, who cluster in churches, know that “if the grain of wheat does not die...”. The process of transforming materials nourished by death is the mechanism needed for any creative act. Why adhere to imposed limits? Ashes become a pictorial substance, saliva soaking cigarette paper [“1933”, 2011] is at the origins of a monochromatic painting... All these elements confirm the notion of art-making as a constant process of manipulation. A small, single gesture, or a slight exageration is sometimes enough. The works are fraught with several possible reifications: it is enough to freeze the moments of the permanent cycle to suggest that each death is an opportunity for new life.

Some pieces are characterised by their twisted, shattered nature, suddenly torn from the street. Some fragments, taken straight from the outside world, appear as memories. [Cambiare la propria mente è facile se cambi prima l’altezza, 2011; Dew Drops (Frammento di opera d’arte rinvenuta durante la mostra Over the Edge a Gent nell’anno 2000) 2011].

Their current exhibition immobilises their shifting reality and breaks their chronology. The intent is to show the fragility of our own present, the impossibility of keeping it or, simply, of sparing it from the archeology of the future. Artistic order is reversed. It is not art that should be protected or restored in our temples–museums any more. The priority here is preserving reality and our daily experiences through art. The essence of reality is its fragility and is rendered visible by its broken expressions. Wasn’t it arrogant of artists to proclaim themselves interpreters of the world, by imprisoning it in the useless shackles of transitory parameters? Yes, look shrewdly at reality, but with the distance and the gap its own nature imposes and above all, by paying attention to the way we look at things.

In Vedovamazzei there is widespread disappointment that entails a certain will to break with the commercial system of lists of artists and consumer works. An “offside” attitude that makes sure the rules of others are not neglected. The traditional notion that someone who is self-aware might take hold of the world through art is questioned, while art might in turn be transmitted by a property deed. The point is to wonder about such a twofold illusion, whose denunciation dates back to Dada, but is far from extinct. The Dadaist affinity explains that the work consists largely of a ready-made collection that comes from very diverse realms: the deceased father’s jacket [Father, 2010/2011] whose pockets have not even been emptied yet, bathroom towels, telephone numbers [WIRELESS, 2008], mattresses... [DDR/My Weakness, 2000/2012]. Vedovamazzei is in itself ready-made: the name was found on a tombstone in an Italian cemetery.

The surface of reality often presents itself to our Widow as a fragment pulled out and torn and, sometimes, under a ready-made guise. The loan of these various objects is, for a start, an act of frankness: immediate reality is pronounced as such. But their shift unleashes the clauses of the tacit contract that binds all artists to truth. The material already engenders an unprecedented production. Vedovamazzei reproduces exact fragments of everyday life (a concrete slab); envelopes [The Last Italian Envelope 1, 2009, Dew Drops-2000, We Need Imperfections to Be Imperfect, 1, 2010] turned into wood; garden [Go Wherever You Want, Bring Me Whatever You Wish, 2000-...]. Just this sole forgery is enough to restore the power of imbuing affection and singularity into what was nothing but banality or indifference.

The little intimate paintings of flowers [DEL VECCHIO GEORGE (fiori) 2010] or of geometrical motifs [CLISBY WILLIE, 2010] possess in themselves a decorative quality able to seduce. But then, why return to these post-war topics? Reifying a modernist ambition to become old-fashioned? To play with the clichés of post-modernism and their rules of repetition? Or rather to infiltrate secret signs into devices that would be devoid of meaning in their absence?

Sometimes, the point is to detect shameful and untold things about our controlled societies. Beautiful, charming motifs hand in hand with accounts of capital punishment. The body is absent from the electric chair, but its subjective rediscovery is demanded by this small sedimentation, more effective than a cry. A change occurs inside this miniscule grey layer, like a particle that becomes alive. It is more convincing than a speech intended to shame our democratic institutions. This way, hardly visible and working underground, is how Vedovamazzei master a work that restores the ability of our consciousness to assume responsibilities.

The extreme cult of gesture in no way diminishes their commitment or alertness. It is better to dream and discreetly proceed to dream again than to whine or give oneself airs. A widow knows a lot about orphans. She knows that it is useless to only touch upon misery. She would rather remember that everybody is vulnerable – her, them, us, and the powerful, too. She would rather work on the way we look at things. The Other is like us, always us, despite appearances or because of them. To help the Other, and ourselves as well, we start by offering her our respect. Here it is what the Widow shows us with dignity.

Natacha Carron Vullierme