The New International

01 Aug - 21 Sep 2014

Danh Vō, We The People (detail), 2011–2014

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Foreground: Danh Vō, We The People (detail), 2011–2014

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Background (left): Makiko Kudo, Manager of the end of the world, 2010

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Background (right): Santiago Sierra, 250 cm line tattooed on the backs of 6 paid people, Espacio Aglutinador, Havana, December 1999

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Background (left): Makiko Kudo, Manager of the end of the world, 2010

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Background (right): Santiago Sierra, 250 cm line tattooed on the backs of 6 paid people, Espacio Aglutinador, Havana, December 1999

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Foreground: Danh Vō, We The People (detail), 2011–2014

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Background: Goshka Macuga, Of what is, that it is; of what is not, that is not 2, 2012

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Background: Goshka Macuga, Of what is, that it is; of what is not, that is not 2, 2012

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

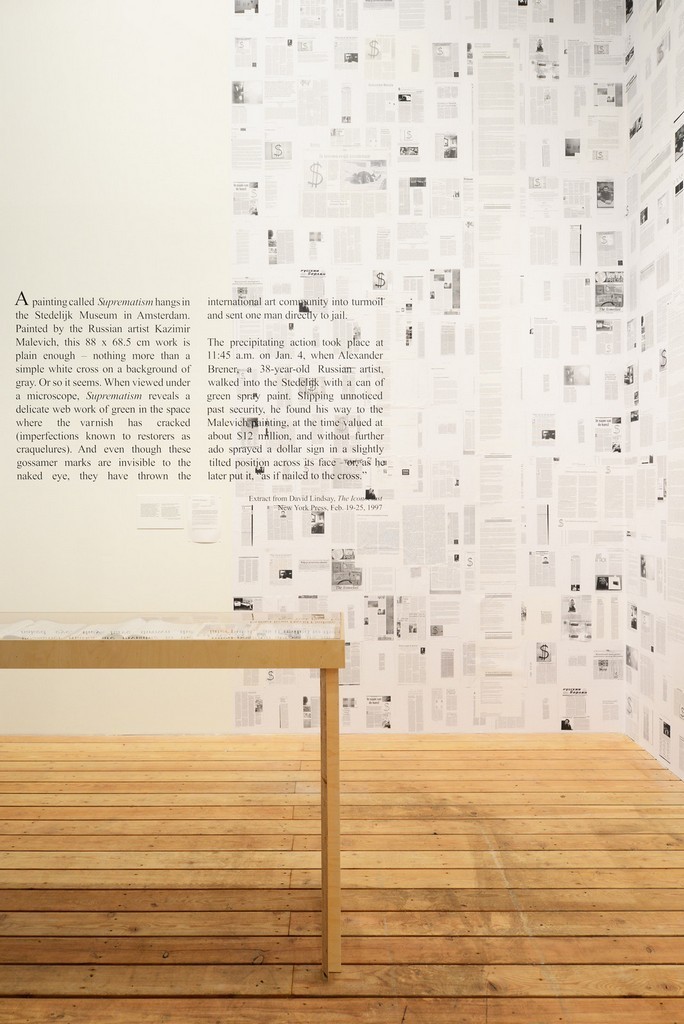

Installation view of a project about Alexander Brener, with the involvement of Michael Benson, Kazimir Malevich, Judith Schoneveld, Alexander Sokolov, Olga Stolpovskaya, Dmitry Troitsky, Harmen Verbrugge, Kamiel Verschuren, and others

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Installation view of a project about Alexander Brener, with the involvement of Michael Benson, Kazimir Malevich, Judith Schoneveld, Alexander Sokolov, Olga Stolpovskaya, Dmitry Troitsky, Harmen Verbrugge, Kamiel Verschuren, and others

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

The New International, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014

Photo: Ilya Ivanov

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

THE NEW INTERNATIONAL

1 August – 21 September 2014

Curated by Kate Fowle, Garage Chief Curator.

The New International is the latest in a series of projects at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art to focus on the 1990s as a significant turning point in contemporary art practices around the world.

Navigating the prevailing discourses after 1989, including the end of the Cold War, the social impact of late capitalism, and an escalating fear of terrorism, the exhibition draws on two generations of artists—those who rose to international attention and those who came of age during the decade.

The artists’ experiences span divergent geographies, and their practices resist national or mono-cultural categories. Instead, they juxtapose plural temporalities and perceptions in order to engage audiences visually, physically, and psychologically in nuanced worldviews. Exploring how new approaches in art challenged dominant perspectives on issues such as identity politics, the U.S. War on Culture, and the former East-West divide, each artist presented in The New International has developed a singular approach to making work that lays the foundation for a new understanding of what the concept of “international” can mean. Recognizing the term as one that is frequently used as interchangeable with “foreign,” as well as one that now implies understanding the self in relation to a bigger viewpoint as opposed to a unilateral nationalism, the new internationalism slows down the onset of a fully-globalized world. In other words, it is a way to describe how individuals share, understand, or experience context-specific situations without universalizing the outcomes.

In art world terms, the potential for a new concept of the international started to form in the 1990s with the expansion of biennials around the globe, expanding art centers, and the increased movement—through communication and travel—afforded to artists and curators. Responding to the larger social and political contexts in which this emerging cultural space was being created, the artists who constitute a new international perspective make fresh connections between events, actions, and ideologies. Fusing activist and aesthetic languages, they favor discourse over polemics, creating works that contribute subtle nuances to topics such as gender, nationalism, class, economics, capital, the media, and institutional critique.

To coincide with The New International, a reader will be published that charts the defining events through which an international dialog emerged from, and with, practitioners in Moscow.

The New International is part of a series of projects at Garage that focus on the 1990s as a turning point in contemporary art practice. Past projects include Reconstruction 1: 1990–1995 and Reconstruction 2: 1996–2000, in collaboration with the Ekaterina Foundation, which was the first survey of Moscow art life through the decade. Forthcoming is 89plus RUSSIA, developed in collaboration with curators Hans Ulrich Obrist and Simon Castets, as part of the Garage Field Research program. Launched during The New International, it will involve a year-long search for the newest generation of creative minds in Russia, all born in 1989 or later.

ARTISTS

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Johan Grimonprez, IRWIN, Paul Khera, Makiko Kudo, Goshka Macuga, Shirin Neshat, Santiago Sierra, Danh Vō, and a project about Alexander Brener with the involvement of Michael Benson, Kazimir Malevich, Judith Schoneveld, Alexander Sokolov, Olga Stolpovskaya, Dmitry Troitsky, Harmen Verbrugge, Kamiel Verschuren, and others.

ABOUT THE ARTISTS

Felix Gonzalez-Torres (b. 1957, Cuba; d. 1996, USA) blurred the distinctions between public and private space, as well as the different social modes we use to experience the world, employing minimal forms to portray the complexity of life. Culling from both collectively significant and overlooked events, he utilized images of fleeting moments, everyday commercial objects, biographical details, and media evidence of social contradiction. The New International is featuring three works by the artist: Untitled (1991–1993), a billboard piece that consists of images produced from two photographs of birds—with their inherent references to freedom and flight—in cloudy, non-descript skies; Untitled (Couple) (1993), consisting of two strings of light bulbs that can be installed differently each time it is exhibited; and Untitled (Waldheim to the Pope) (1989), one of 55 small C-print jigsaw puzzles based on a newspaper photograph of Kurt Waldheim receiving communion from the Pope. This image of the former United Nations Secretary General and President of Austria, famous for concealing his association with Nazi war crimes, at once insinuates the hypocrisies of culture and the fragility of any image.

Johan Grimonprez (b 1962, Belgium) made his international breakthrough with the 68-minute film essay dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y, which premiered at Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and Documenta X in 1997, breaking new ground in documentary filmmaking. The film tells the story of airplane hijacks, from those staged by the revolutionaries who first gained media coverage with skyjackings in the late 1960s, through to the state-sponsored suitcase bombs on planes in the 1990s. Revealing how the rise of international terrorism changed the course of reportage, the artist reflects on the way in which history has been influenced by the fusion of reality and fiction in the mass media.

Founded in 1983 in Ljubljana, Slovenia while the country was still part of the Yugoslavian Federation, IRWIN consists of five members: Dušan Mandič (b. 1954), Miran Mohar (b. 1958), Andrej Savski (b. 1961), Roman Uranjek (b. 1961), and Borut Vogelnik (b. 1959). IRWIN was also one of the founding members of NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst) in Ljubljana in 1984, established to explore issues related to Slovenian national self-determination. In June 1991 Slovenia became the first country to gain independence from Yugoslavia, prompting NSK’s mission to mutate into a “State in Time” that does not have a specific territory and is not based on nationality. One of the first projects to emerge from this transformation was the NSK Embassy Moscow. Established through collaboration with Apt-Art International in a rented apartment in Moscow, the IRWIN-NSK Embassy was the first project in Russia to establish a direct dialogue with artists from Eastern Europe. For one month in 1992, the temporary institution hosted lectures, debates, and performances with artists, critics, and philosophers under the auspices of the concept “How the East Sees the East.” For The New International this project will be revisited to see what resonance the conversations and ideas behind the Embassy have today.

Paul Khera (b. 1964, UK) is a designer, photographer, architect, and filmmaker. In the 1990s, while working with Vogue magazine as it was planning to launch its Russian issue, Khera discovered that there were very few contemporary Cyrillic typefaces. Desiring to see Russian Vogue launch with a completely new approach to Cyrillic typography (a desire that was never fulfilled), in 1999 Khera began a five-year project called Post Soviet. Ultimately working more closely with subcultures than the mainstream, the designer created a font that offered a contemporary take on both Latin and Cyrillic letters, reflecting the energy of those who would communicate with it. Ten years on, now an artifact of its time, Post Soviet is the font used for all the graphics of The New International exhibition.

Makiko Kudo (b. 1978, Japan) belongs to the generation of artists who came of age during the so-called “lost decade” of 1990s Japan. With natural and social disasters unsettling a culture that was already losing traditional values, living with uncertainty became the norm. For many young people, the best outcome was to resist global capitalism through turning the problems of existence into opportunities for personal freedom. This gave rise to a tendency in art that critic Midori Matsui has named “Micropop,” and of which Kudo is considered to be a part. Her paintings Manager of the end of the world (2010) and Base Ogawa garbage incinerator (2010) draw on places she has passed by, as well as associative memories, to create landscapes that are at once magical and banal—phenomenological, transient worlds with an intimacy that draws in the viewer. Using vibrant color fields woven like tapestries, and expressive brushstrokes that recall Jackson Pollock, Monet, and Rousseau all at once, the artist evokes classical Japanese symbols and Manga-like characters, while painting depictions of non-places that both seduce and repel.

Goshka Macuga (b. 1967, Poland) works across a variety of media, including installation, sculpture, film, photography, architecture, collage, and tapestry. Often featuring subjects from politics, sociology, and ethnography, her works also employ references to herself as a participant in the ever-expanding art world to create another layer of meaning in the critique of curatorial and archival practices. Commissioned for dOCUMENTA (13) in 2012, Of what is, that it is; of what is not, that it is not is a two-part work of photo-based, black-and-white tapestries that are reminiscent of the 16th century tradition of creating allegorical tapestries on a monumental scale that relayed multiple narratives as well as anecdotal details of social and political events. Part 1, which was produced during research in Kabul and presented in Kassel as part of dOCUMENTA (13), depicts a diverse crowd of Afghans and Westerners in front of Darul Aman Palace outside of Kabul. Part 2, which will be featured in The New International, shows a collage of the curators and organizers of dOCUMENTA (13), Occupy protesters, and an art world crowd attending the bi-annual Arnold Bode Prize—named after the founder of documenta—which Macuga was awarded in 2011 for outstanding work in contemporary art. By re-contextualizing historic events in a subjective way, she suggests that history is never objective or conclusive, and reveals the idiosyncrasies of the role of the art institution in presenting issues concerning broader cultural and political concerns.

Although she grew up during a relatively progressive time in Iran, Shirin Neshat (b. 1957) was forced into exile during the 1979 Iranian revolution, becoming involuntarily separated from her family while she studied in California. She has remained based in the United States ever since. Returning to Iran for the first time in the early 1990s, she started to explore the dualities between the political and personal, the individual and the national, created by the restrictions on expression and the activities of women in the country. While resisting polemics in its message, Turbulent (1998)—the artist’s first departure from photography into installation—employs visual opposites such as black/white, male/female, empty/full, traditional/nontraditional, communal/solitary, and rational/irrational to explore the complex intellectual, psychological, and social dimensions of Islamic culture and Muslim women’s’ experience.

Santiago Sierra (b 1966, Spain) creates works that engage in a critical reconsideration of the neutrality of minimalism through photography, video, performance, and sculpture. Produced in many cities across the world and featuring illegal immigrants, prostitutes, junkies, and the unemployed, in nearly all his works the individual becomes an object that can be used or organized. Often seen with their backs to the viewer, the artist’s subjects become anonymous examples of how human dignity is now an economic privilege. For 250 cm line tattooed on the backs of 6 paid people (1999) he invited six unemployed men from Havana to have a line tattooed across their backs in exchange for $30 each. In effect they were hired to become the work of art, which is the resulting two-and-a-half-meter line formed by all the participants when they stand side by side. The monetary transaction, representing a capitalist structure of power, enabled Sierra to produce a photograph that circulates in the art world. In exchange, the participants are literally branded for life.

Danh Vō (b. 1975) left Vietnam with his family during the Cambodian-Vietnamese War. They were rescued at sea by a Danish tanker and Vō eventually became a Danish citizen. His conceptual artworks and installations subtly draw on elements of his lived experiences, in the context of broader historical, social, or political phenomena, to address issues relating to identity and belonging, authorial status, ownership, and the role of personal relationships. Vō’s project We The People (detail) (2011–14) is parts of a life-size replica of the Statue of Liberty. The project takes its name from the first three words of the U.S. Constitution, which promotes human rights through the establishment of justice, domestic tranquility, welfare, and promises to “secure the Blessings of Liberty.” By replicating one of the most famous monuments to freedom in the world, but in parts that will never be seen all together, inherent in We The People is the failure to implement the political ideals imbued by the statue. Now, the first three words of the Constitution sound like the cries of the “99%,” rather than the words underlying the belief that it is the people who form a polity.

Alexander Brener (b. 1957, Kazakhstan, former USSR) gained international notoriety through performing provocative public actions in Russia, as well as in European museums and exhibitions, during the 1990s. While he does not consider himself to be a part of a movement, or his actions to contribute to a generational zeitgeist, he became known as a proponent of Moscow Actionism, and his activities generated a great deal of discussion and creative responses from other artists, critics, and curators. While his involvement in the “professional” art world was short-lived—he is now more closely engaged with samizdat, fanzines, and the oral tradition in what he describes as the “liberation of everyday life”—his impact was not. Many never saw the various actions he performed, but the rumors and storytelling around them meant that they became legendary. In short, Brener is a mythological figure whose works few have experienced firsthand.

The New International focuses on his action at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1997, where he spray-painted a green dollar sign on Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematisme, for which he faced a trial and short jail sentence. At the time, this provoked a discussion about whether his action was a radical intervention or mere vandalism. Many journalists denied it had any value, while others, including the editor of Flash Art, felt that it warranted closer consideration. Artists in Moscow and further afield made work in response to the action, while others rallied to support the artist while he was in jail. For this exhibition, related press, artworks, films, and other forms of documentation will explore the way in which Brener’s action impacted on an art community attempting to make sense of the politics of art. The display is produced with the involvement of Michael Benson, Kazimir Malevich, Judith Schoneveld, Alexander Sokolov, Olga Stolpovskaya, Dmitry Troitsky, Harmen Verbrugge, and Kamiel Verschuren, among others.

1 August – 21 September 2014

Curated by Kate Fowle, Garage Chief Curator.

The New International is the latest in a series of projects at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art to focus on the 1990s as a significant turning point in contemporary art practices around the world.

Navigating the prevailing discourses after 1989, including the end of the Cold War, the social impact of late capitalism, and an escalating fear of terrorism, the exhibition draws on two generations of artists—those who rose to international attention and those who came of age during the decade.

The artists’ experiences span divergent geographies, and their practices resist national or mono-cultural categories. Instead, they juxtapose plural temporalities and perceptions in order to engage audiences visually, physically, and psychologically in nuanced worldviews. Exploring how new approaches in art challenged dominant perspectives on issues such as identity politics, the U.S. War on Culture, and the former East-West divide, each artist presented in The New International has developed a singular approach to making work that lays the foundation for a new understanding of what the concept of “international” can mean. Recognizing the term as one that is frequently used as interchangeable with “foreign,” as well as one that now implies understanding the self in relation to a bigger viewpoint as opposed to a unilateral nationalism, the new internationalism slows down the onset of a fully-globalized world. In other words, it is a way to describe how individuals share, understand, or experience context-specific situations without universalizing the outcomes.

In art world terms, the potential for a new concept of the international started to form in the 1990s with the expansion of biennials around the globe, expanding art centers, and the increased movement—through communication and travel—afforded to artists and curators. Responding to the larger social and political contexts in which this emerging cultural space was being created, the artists who constitute a new international perspective make fresh connections between events, actions, and ideologies. Fusing activist and aesthetic languages, they favor discourse over polemics, creating works that contribute subtle nuances to topics such as gender, nationalism, class, economics, capital, the media, and institutional critique.

To coincide with The New International, a reader will be published that charts the defining events through which an international dialog emerged from, and with, practitioners in Moscow.

The New International is part of a series of projects at Garage that focus on the 1990s as a turning point in contemporary art practice. Past projects include Reconstruction 1: 1990–1995 and Reconstruction 2: 1996–2000, in collaboration with the Ekaterina Foundation, which was the first survey of Moscow art life through the decade. Forthcoming is 89plus RUSSIA, developed in collaboration with curators Hans Ulrich Obrist and Simon Castets, as part of the Garage Field Research program. Launched during The New International, it will involve a year-long search for the newest generation of creative minds in Russia, all born in 1989 or later.

ARTISTS

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Johan Grimonprez, IRWIN, Paul Khera, Makiko Kudo, Goshka Macuga, Shirin Neshat, Santiago Sierra, Danh Vō, and a project about Alexander Brener with the involvement of Michael Benson, Kazimir Malevich, Judith Schoneveld, Alexander Sokolov, Olga Stolpovskaya, Dmitry Troitsky, Harmen Verbrugge, Kamiel Verschuren, and others.

ABOUT THE ARTISTS

Felix Gonzalez-Torres (b. 1957, Cuba; d. 1996, USA) blurred the distinctions between public and private space, as well as the different social modes we use to experience the world, employing minimal forms to portray the complexity of life. Culling from both collectively significant and overlooked events, he utilized images of fleeting moments, everyday commercial objects, biographical details, and media evidence of social contradiction. The New International is featuring three works by the artist: Untitled (1991–1993), a billboard piece that consists of images produced from two photographs of birds—with their inherent references to freedom and flight—in cloudy, non-descript skies; Untitled (Couple) (1993), consisting of two strings of light bulbs that can be installed differently each time it is exhibited; and Untitled (Waldheim to the Pope) (1989), one of 55 small C-print jigsaw puzzles based on a newspaper photograph of Kurt Waldheim receiving communion from the Pope. This image of the former United Nations Secretary General and President of Austria, famous for concealing his association with Nazi war crimes, at once insinuates the hypocrisies of culture and the fragility of any image.

Johan Grimonprez (b 1962, Belgium) made his international breakthrough with the 68-minute film essay dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y, which premiered at Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and Documenta X in 1997, breaking new ground in documentary filmmaking. The film tells the story of airplane hijacks, from those staged by the revolutionaries who first gained media coverage with skyjackings in the late 1960s, through to the state-sponsored suitcase bombs on planes in the 1990s. Revealing how the rise of international terrorism changed the course of reportage, the artist reflects on the way in which history has been influenced by the fusion of reality and fiction in the mass media.

Founded in 1983 in Ljubljana, Slovenia while the country was still part of the Yugoslavian Federation, IRWIN consists of five members: Dušan Mandič (b. 1954), Miran Mohar (b. 1958), Andrej Savski (b. 1961), Roman Uranjek (b. 1961), and Borut Vogelnik (b. 1959). IRWIN was also one of the founding members of NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst) in Ljubljana in 1984, established to explore issues related to Slovenian national self-determination. In June 1991 Slovenia became the first country to gain independence from Yugoslavia, prompting NSK’s mission to mutate into a “State in Time” that does not have a specific territory and is not based on nationality. One of the first projects to emerge from this transformation was the NSK Embassy Moscow. Established through collaboration with Apt-Art International in a rented apartment in Moscow, the IRWIN-NSK Embassy was the first project in Russia to establish a direct dialogue with artists from Eastern Europe. For one month in 1992, the temporary institution hosted lectures, debates, and performances with artists, critics, and philosophers under the auspices of the concept “How the East Sees the East.” For The New International this project will be revisited to see what resonance the conversations and ideas behind the Embassy have today.

Paul Khera (b. 1964, UK) is a designer, photographer, architect, and filmmaker. In the 1990s, while working with Vogue magazine as it was planning to launch its Russian issue, Khera discovered that there were very few contemporary Cyrillic typefaces. Desiring to see Russian Vogue launch with a completely new approach to Cyrillic typography (a desire that was never fulfilled), in 1999 Khera began a five-year project called Post Soviet. Ultimately working more closely with subcultures than the mainstream, the designer created a font that offered a contemporary take on both Latin and Cyrillic letters, reflecting the energy of those who would communicate with it. Ten years on, now an artifact of its time, Post Soviet is the font used for all the graphics of The New International exhibition.

Makiko Kudo (b. 1978, Japan) belongs to the generation of artists who came of age during the so-called “lost decade” of 1990s Japan. With natural and social disasters unsettling a culture that was already losing traditional values, living with uncertainty became the norm. For many young people, the best outcome was to resist global capitalism through turning the problems of existence into opportunities for personal freedom. This gave rise to a tendency in art that critic Midori Matsui has named “Micropop,” and of which Kudo is considered to be a part. Her paintings Manager of the end of the world (2010) and Base Ogawa garbage incinerator (2010) draw on places she has passed by, as well as associative memories, to create landscapes that are at once magical and banal—phenomenological, transient worlds with an intimacy that draws in the viewer. Using vibrant color fields woven like tapestries, and expressive brushstrokes that recall Jackson Pollock, Monet, and Rousseau all at once, the artist evokes classical Japanese symbols and Manga-like characters, while painting depictions of non-places that both seduce and repel.

Goshka Macuga (b. 1967, Poland) works across a variety of media, including installation, sculpture, film, photography, architecture, collage, and tapestry. Often featuring subjects from politics, sociology, and ethnography, her works also employ references to herself as a participant in the ever-expanding art world to create another layer of meaning in the critique of curatorial and archival practices. Commissioned for dOCUMENTA (13) in 2012, Of what is, that it is; of what is not, that it is not is a two-part work of photo-based, black-and-white tapestries that are reminiscent of the 16th century tradition of creating allegorical tapestries on a monumental scale that relayed multiple narratives as well as anecdotal details of social and political events. Part 1, which was produced during research in Kabul and presented in Kassel as part of dOCUMENTA (13), depicts a diverse crowd of Afghans and Westerners in front of Darul Aman Palace outside of Kabul. Part 2, which will be featured in The New International, shows a collage of the curators and organizers of dOCUMENTA (13), Occupy protesters, and an art world crowd attending the bi-annual Arnold Bode Prize—named after the founder of documenta—which Macuga was awarded in 2011 for outstanding work in contemporary art. By re-contextualizing historic events in a subjective way, she suggests that history is never objective or conclusive, and reveals the idiosyncrasies of the role of the art institution in presenting issues concerning broader cultural and political concerns.

Although she grew up during a relatively progressive time in Iran, Shirin Neshat (b. 1957) was forced into exile during the 1979 Iranian revolution, becoming involuntarily separated from her family while she studied in California. She has remained based in the United States ever since. Returning to Iran for the first time in the early 1990s, she started to explore the dualities between the political and personal, the individual and the national, created by the restrictions on expression and the activities of women in the country. While resisting polemics in its message, Turbulent (1998)—the artist’s first departure from photography into installation—employs visual opposites such as black/white, male/female, empty/full, traditional/nontraditional, communal/solitary, and rational/irrational to explore the complex intellectual, psychological, and social dimensions of Islamic culture and Muslim women’s’ experience.

Santiago Sierra (b 1966, Spain) creates works that engage in a critical reconsideration of the neutrality of minimalism through photography, video, performance, and sculpture. Produced in many cities across the world and featuring illegal immigrants, prostitutes, junkies, and the unemployed, in nearly all his works the individual becomes an object that can be used or organized. Often seen with their backs to the viewer, the artist’s subjects become anonymous examples of how human dignity is now an economic privilege. For 250 cm line tattooed on the backs of 6 paid people (1999) he invited six unemployed men from Havana to have a line tattooed across their backs in exchange for $30 each. In effect they were hired to become the work of art, which is the resulting two-and-a-half-meter line formed by all the participants when they stand side by side. The monetary transaction, representing a capitalist structure of power, enabled Sierra to produce a photograph that circulates in the art world. In exchange, the participants are literally branded for life.

Danh Vō (b. 1975) left Vietnam with his family during the Cambodian-Vietnamese War. They were rescued at sea by a Danish tanker and Vō eventually became a Danish citizen. His conceptual artworks and installations subtly draw on elements of his lived experiences, in the context of broader historical, social, or political phenomena, to address issues relating to identity and belonging, authorial status, ownership, and the role of personal relationships. Vō’s project We The People (detail) (2011–14) is parts of a life-size replica of the Statue of Liberty. The project takes its name from the first three words of the U.S. Constitution, which promotes human rights through the establishment of justice, domestic tranquility, welfare, and promises to “secure the Blessings of Liberty.” By replicating one of the most famous monuments to freedom in the world, but in parts that will never be seen all together, inherent in We The People is the failure to implement the political ideals imbued by the statue. Now, the first three words of the Constitution sound like the cries of the “99%,” rather than the words underlying the belief that it is the people who form a polity.

Alexander Brener (b. 1957, Kazakhstan, former USSR) gained international notoriety through performing provocative public actions in Russia, as well as in European museums and exhibitions, during the 1990s. While he does not consider himself to be a part of a movement, or his actions to contribute to a generational zeitgeist, he became known as a proponent of Moscow Actionism, and his activities generated a great deal of discussion and creative responses from other artists, critics, and curators. While his involvement in the “professional” art world was short-lived—he is now more closely engaged with samizdat, fanzines, and the oral tradition in what he describes as the “liberation of everyday life”—his impact was not. Many never saw the various actions he performed, but the rumors and storytelling around them meant that they became legendary. In short, Brener is a mythological figure whose works few have experienced firsthand.

The New International focuses on his action at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1997, where he spray-painted a green dollar sign on Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematisme, for which he faced a trial and short jail sentence. At the time, this provoked a discussion about whether his action was a radical intervention or mere vandalism. Many journalists denied it had any value, while others, including the editor of Flash Art, felt that it warranted closer consideration. Artists in Moscow and further afield made work in response to the action, while others rallied to support the artist while he was in jail. For this exhibition, related press, artworks, films, and other forms of documentation will explore the way in which Brener’s action impacted on an art community attempting to make sense of the politics of art. The display is produced with the involvement of Michael Benson, Kazimir Malevich, Judith Schoneveld, Alexander Sokolov, Olga Stolpovskaya, Dmitry Troitsky, Harmen Verbrugge, and Kamiel Verschuren, among others.