Inventing a Future

26 Jan - 13 Mar 2013

© Ryan Gander

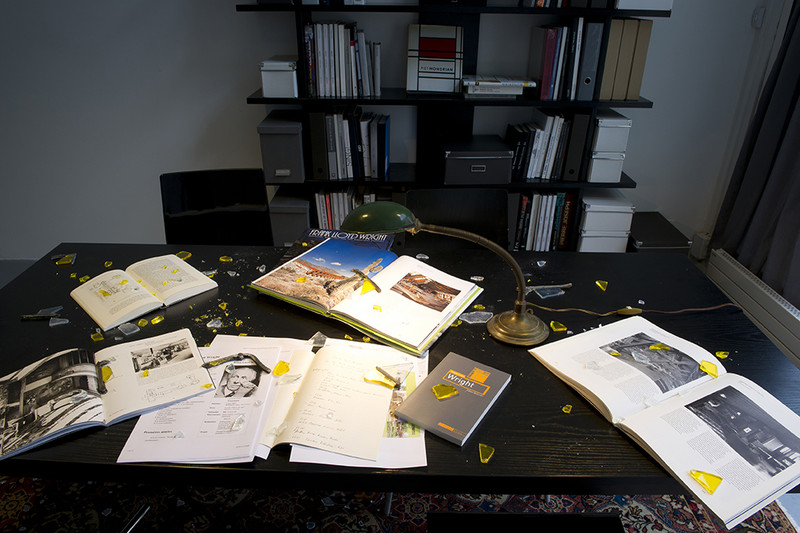

Untitled, 2010

Installation (Detail)

Exhibition view: Inventing a future, gb agency Paris, 2013

Photo: Marc Domage

Untitled, 2010

Installation (Detail)

Exhibition view: Inventing a future, gb agency Paris, 2013

Photo: Marc Domage

INVENTING A FUTURE

26 January - 13 March 2013

with works by Beatrice Gibson, Nikhil Chopra, Ryan Gander, Július Koller / Roman Ondák, Jiří Kovanda, Deimantas Narkevičius, Yann Sérandour.

This group show is inspired by a citation used in one of Jiří Kovanda's collages named ‘The end of utopia’:

"The euphoria has ended. Let's start it again."

This injunction could sound like an acknowledgement, one of some kind of disillusion. The end of utopias. The causes remain unknown, but it announces a breaking point. We are forced to a new beginning. Blank screen at the end of an apocalyptic movie : what we've known is no more, let's start over again.

But all the pieces shown in the exhibition share this ambiguity : announcing a possible failure or the end of an era, they nevertheless create at the same time a new field of possibilities. Between anachronism, retro-futurism and fictionalized past, they fall within an odd and non-lineal temporality : per se, they contain at once the idea of the past, of the present and of the future. The artists shown in the exhibition are indeed not that interested in the end of a story but instead in the fantasy of rewriting, of resumption, of projection. Against a backdrop of collective utopias, this will to initiate a form of renewal, to replay the loop of history, firstly comes from an intimate desire. Every narrative, in the service of the playful, poetic or political will of creation, can be allowed to give up the truthful to become falsifying. Once the limits are set, everything is made possible.

Space upstairs

In the video ‘Agatha’ (2012), we only hear one voice - that of Beatrice Gibson, the author of the work but also its narrator. Maintaining a troubling ambiguity about 'her' identity (and about 'her' gender, especially), 'she' relates a strange tale told in the first person and in the past. An under-qualified scientist sent on a reconnaissance mission to a planet very similar to Earth, she talks about her encounter with the locals - human beings she can’t define the sex of who communicate solely through the musicality of their gestures or by changing colour.

This sci-fi story (are we in an hypothetical near future, in a past that could have been, in a parallel present world ?) is actually based on recordings from 1967 where Cornelius Cardew (an English experimental music composer who died in 1981) tells one of his dreams. From the unconscious and intimate imagination of someone else, stated as a possibly lived story (we always speak about our dreams in the past, never in the conditional), Beatrice Gibson builds up new fictional and cinematographic stakes. The intimate is here treated as a material irrigating the whole film in a subliminal and subterranean way, the ambiguity of the story never being removed nor resolved by the spatiotemporal indecision proper to sci-fi.

The installation ‘On the subject of horizontals and verticals a ‘Bird-walk’ is added (The remnants of Theo and Piet’s fall from 1924 through Frank’s living room window at Taliesin, during a struggle brought on by an argument over the dynamic aspect of the diagonal line again)’ (2010) by Ryan Gander has been previoulsy presented in the reading room of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Visitors encountered a scene of apparent catastrophe that relates to Gander’s ongoing exploration of the schism between the Dutch artists Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) and Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931). These friends and creative collaborators severed their relationship in 1924 due to van Doesburg’s belief in the diagonal line as a valid element in abstract art, which conflicted with Mondrian’s insistence on a reductive visual language consisting of only gridded horizontals and verticals. Gander imagines this artistic dogmatism provoking a violent struggle between the two men that sends them crashing through a stained-glass window in the home of Frank Lloyd Wright, the architect of the Guggenheim Museum. In a mysterious temporal and spatial discontinuity, the debris from this accident that landed in the reading room, showering fragments of glass and lead over books about Wright’s life and work, is replayed in the gallery space. Aware of the failure of the utopian ambitions of the modernist movement, Ryan Gander restages them here, transforming them into pretexts for a fiction.

Yann Sérandour conceived the piece ‘Perfect Lovers’ (2008) when he was invited by the museum CGAC in Santiago de Compostela in 2008. The artist used the poster of the last exhibition of Felix Gonzales-Torres' work while he was still alive, announcing his exhibition at CGAC in 1995. On the poster is reproduced the work ‘Untitled (Perfect Lovers)’, realized just after the death of Gonzales-Torres’ lover. Two identical clocks, placed side by side on the wall, initially set to the same time, but which will inevitably fall out of sync. A demonstration of entropy, here frozen on the glossy paper, to which Yann Sérandour adds another temporal and symbolic layer of reading : a real clock has been fixed on the existing one to the right, giving the real time.

Space downstairs

The twelve drawings of the installation ‘Teenagers’ (2002) have been realized by two teenagers: Július Koller and Roman Ondák. Though made several years apart, their drawings are presented together here, grouped in pairs that highlight likenesses and differences rather than questions of influence or youthful talent. Belonging to two different generations (Koller has lived through state communist ideology, Ondák the entry of Slovakia into the E.U..), they meet here through this still undefined state which is adolescence : close friends when they conceived this piece together, they were only children when they realized these drawings. ‘Teenagers’ introduces some recurrences in Roman Ondák's work : the connections between reality and its staging ; the relations between the unique and unpredictable moment and its repetition ; the use of memory and its representation, which offers a free space for the imagination and the unconscious . Like a reversed premonition, the elder Július Koller’s bottle on a black square parallels Ondák’s rocket zooming through space. We remember then the constant interest Július Koller (who has also questioned notions of otherness, inventing fictitious interlocutors) has had for the mysteries of the cosmos, and his ‘futurological’ vision - neither present nor future, a temporality with its discontinuities, anachronisms and parallel times.

In his film 'The Dud Effect' (2008), Deimantas Narkevičius stages an event which has never taken place : the launch of nuclear rockets in the seventies from a Soviet base located in Lithuania. If this base truly exists, it was closed in 1977 and no missile has ever been launched from there. Helped by testimonies of Russian officers having served there, Narkevičius went to film the ruins of the base and the structure of the subterranean installations. He also used archive images from the time. The artist then simply used very modest means of film collage, putting the black and white photos together with a soundtrack of commands in Russian. Anti-spectacular, the video is interested in the launch rather than its impact, the whole being filmed as a clinical description of a daily administrative routine. In the last sequences of the film, shots of imprecise landscapes could be that of a possible post-apocalyptic world or simple ruins of time, the traces of the Soviet empire’s fall. Through its experimental forms and its plastic collages, Deimantas Narkevičius revisits here a period when the utopia failed ; by infiltrating History by means of a fiction pretending to be a documentary, he re-enacts the past in order to signal a latent conditional, a future that is still possible.

Indian artist Nikhil Chopra’s practice ranges through performance, theatre, improvisation, painting, photography, sculpture, drawing and installations. His work is a critical investigation of post-colonial Indian history, which he has described as being « obsessed by nostalgia for the British Raj » (the period of British domination of the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947). Using the immediacy and the urgency of live art, he explores themes such as colonialism, identity, exoticism. Each time he’s invited to participate in a project, he activates a fictive persona of his creation, loosely based on his own story or on the collective history of his country. Each performance starts with simple daily acts such as eating, resting, washing, dressing, drawing, making clothes... that acquire the value of rituals.

The four large-framed photographies shown in the exhibition are linked to a 99-hour performance of his entitled ‘Inside out’ (2012), made in San Gimignano. In the guise of a Renaissance wandering painter inspired by Benozzo Gozzoli, the artist (silent for 99 hours) walked around in the streets of the small town and in the surrounding area and produced a series of drawings of San Gimignano and of the Tuscan landscape. Less political than his previous performances, it is here a site-specific work that echoes perfectly the Tuscan landscapes ; traces of medieval and renaissance art are absorbed, digested, retranscribed by and onto the artist’s own body, highlighting a collision between different temporalities.

On the other hand, his character in the performance ‘Yog Raj Chitrakar visits Lal Chowk’ (2007) is inspired by his grandfather. This man, who studied painting in England in the 1930s, used to paint landscapes of Kashmir - the place he was native of and which became inaccessible to him and his family after 1989, when the separatist movement began to gain ground. His large paintings, which adorned the walls of Nikhil Chopra’s family home, were like windows on the past and a way for him to travel mentally beyond the limits set by politics. For this performance, he goes to Srinagar, the summer capital of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir : if the political pressures are lower nowadays, the police presence is still very strong. The performance starts with Chopra’s ritual of transformation (clothing, doing his hair, putting on make-up), before he starts walking around the city. Once arrived in Lal Chowk, a central neighborhood of the city, a crowd quickly gathers up around him while he starts drawing on the floor with charcoal and chalk. Against his first intention, what was meant to be a simple act - drawing - is turned into a political public act of resistance : the crowd, quickly controled by the police authorities, won’t be dissuaded from seeing the performance till the end. By a ritual and intimate constraint, Chopra revisits the colonial past and highlights the political transformations both present and future. Almost unintentionally, the autobiographical meets collective history ; the circle is complete.

26 January - 13 March 2013

with works by Beatrice Gibson, Nikhil Chopra, Ryan Gander, Július Koller / Roman Ondák, Jiří Kovanda, Deimantas Narkevičius, Yann Sérandour.

This group show is inspired by a citation used in one of Jiří Kovanda's collages named ‘The end of utopia’:

"The euphoria has ended. Let's start it again."

This injunction could sound like an acknowledgement, one of some kind of disillusion. The end of utopias. The causes remain unknown, but it announces a breaking point. We are forced to a new beginning. Blank screen at the end of an apocalyptic movie : what we've known is no more, let's start over again.

But all the pieces shown in the exhibition share this ambiguity : announcing a possible failure or the end of an era, they nevertheless create at the same time a new field of possibilities. Between anachronism, retro-futurism and fictionalized past, they fall within an odd and non-lineal temporality : per se, they contain at once the idea of the past, of the present and of the future. The artists shown in the exhibition are indeed not that interested in the end of a story but instead in the fantasy of rewriting, of resumption, of projection. Against a backdrop of collective utopias, this will to initiate a form of renewal, to replay the loop of history, firstly comes from an intimate desire. Every narrative, in the service of the playful, poetic or political will of creation, can be allowed to give up the truthful to become falsifying. Once the limits are set, everything is made possible.

Space upstairs

In the video ‘Agatha’ (2012), we only hear one voice - that of Beatrice Gibson, the author of the work but also its narrator. Maintaining a troubling ambiguity about 'her' identity (and about 'her' gender, especially), 'she' relates a strange tale told in the first person and in the past. An under-qualified scientist sent on a reconnaissance mission to a planet very similar to Earth, she talks about her encounter with the locals - human beings she can’t define the sex of who communicate solely through the musicality of their gestures or by changing colour.

This sci-fi story (are we in an hypothetical near future, in a past that could have been, in a parallel present world ?) is actually based on recordings from 1967 where Cornelius Cardew (an English experimental music composer who died in 1981) tells one of his dreams. From the unconscious and intimate imagination of someone else, stated as a possibly lived story (we always speak about our dreams in the past, never in the conditional), Beatrice Gibson builds up new fictional and cinematographic stakes. The intimate is here treated as a material irrigating the whole film in a subliminal and subterranean way, the ambiguity of the story never being removed nor resolved by the spatiotemporal indecision proper to sci-fi.

The installation ‘On the subject of horizontals and verticals a ‘Bird-walk’ is added (The remnants of Theo and Piet’s fall from 1924 through Frank’s living room window at Taliesin, during a struggle brought on by an argument over the dynamic aspect of the diagonal line again)’ (2010) by Ryan Gander has been previoulsy presented in the reading room of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Visitors encountered a scene of apparent catastrophe that relates to Gander’s ongoing exploration of the schism between the Dutch artists Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) and Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931). These friends and creative collaborators severed their relationship in 1924 due to van Doesburg’s belief in the diagonal line as a valid element in abstract art, which conflicted with Mondrian’s insistence on a reductive visual language consisting of only gridded horizontals and verticals. Gander imagines this artistic dogmatism provoking a violent struggle between the two men that sends them crashing through a stained-glass window in the home of Frank Lloyd Wright, the architect of the Guggenheim Museum. In a mysterious temporal and spatial discontinuity, the debris from this accident that landed in the reading room, showering fragments of glass and lead over books about Wright’s life and work, is replayed in the gallery space. Aware of the failure of the utopian ambitions of the modernist movement, Ryan Gander restages them here, transforming them into pretexts for a fiction.

Yann Sérandour conceived the piece ‘Perfect Lovers’ (2008) when he was invited by the museum CGAC in Santiago de Compostela in 2008. The artist used the poster of the last exhibition of Felix Gonzales-Torres' work while he was still alive, announcing his exhibition at CGAC in 1995. On the poster is reproduced the work ‘Untitled (Perfect Lovers)’, realized just after the death of Gonzales-Torres’ lover. Two identical clocks, placed side by side on the wall, initially set to the same time, but which will inevitably fall out of sync. A demonstration of entropy, here frozen on the glossy paper, to which Yann Sérandour adds another temporal and symbolic layer of reading : a real clock has been fixed on the existing one to the right, giving the real time.

Space downstairs

The twelve drawings of the installation ‘Teenagers’ (2002) have been realized by two teenagers: Július Koller and Roman Ondák. Though made several years apart, their drawings are presented together here, grouped in pairs that highlight likenesses and differences rather than questions of influence or youthful talent. Belonging to two different generations (Koller has lived through state communist ideology, Ondák the entry of Slovakia into the E.U..), they meet here through this still undefined state which is adolescence : close friends when they conceived this piece together, they were only children when they realized these drawings. ‘Teenagers’ introduces some recurrences in Roman Ondák's work : the connections between reality and its staging ; the relations between the unique and unpredictable moment and its repetition ; the use of memory and its representation, which offers a free space for the imagination and the unconscious . Like a reversed premonition, the elder Július Koller’s bottle on a black square parallels Ondák’s rocket zooming through space. We remember then the constant interest Július Koller (who has also questioned notions of otherness, inventing fictitious interlocutors) has had for the mysteries of the cosmos, and his ‘futurological’ vision - neither present nor future, a temporality with its discontinuities, anachronisms and parallel times.

In his film 'The Dud Effect' (2008), Deimantas Narkevičius stages an event which has never taken place : the launch of nuclear rockets in the seventies from a Soviet base located in Lithuania. If this base truly exists, it was closed in 1977 and no missile has ever been launched from there. Helped by testimonies of Russian officers having served there, Narkevičius went to film the ruins of the base and the structure of the subterranean installations. He also used archive images from the time. The artist then simply used very modest means of film collage, putting the black and white photos together with a soundtrack of commands in Russian. Anti-spectacular, the video is interested in the launch rather than its impact, the whole being filmed as a clinical description of a daily administrative routine. In the last sequences of the film, shots of imprecise landscapes could be that of a possible post-apocalyptic world or simple ruins of time, the traces of the Soviet empire’s fall. Through its experimental forms and its plastic collages, Deimantas Narkevičius revisits here a period when the utopia failed ; by infiltrating History by means of a fiction pretending to be a documentary, he re-enacts the past in order to signal a latent conditional, a future that is still possible.

Indian artist Nikhil Chopra’s practice ranges through performance, theatre, improvisation, painting, photography, sculpture, drawing and installations. His work is a critical investigation of post-colonial Indian history, which he has described as being « obsessed by nostalgia for the British Raj » (the period of British domination of the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947). Using the immediacy and the urgency of live art, he explores themes such as colonialism, identity, exoticism. Each time he’s invited to participate in a project, he activates a fictive persona of his creation, loosely based on his own story or on the collective history of his country. Each performance starts with simple daily acts such as eating, resting, washing, dressing, drawing, making clothes... that acquire the value of rituals.

The four large-framed photographies shown in the exhibition are linked to a 99-hour performance of his entitled ‘Inside out’ (2012), made in San Gimignano. In the guise of a Renaissance wandering painter inspired by Benozzo Gozzoli, the artist (silent for 99 hours) walked around in the streets of the small town and in the surrounding area and produced a series of drawings of San Gimignano and of the Tuscan landscape. Less political than his previous performances, it is here a site-specific work that echoes perfectly the Tuscan landscapes ; traces of medieval and renaissance art are absorbed, digested, retranscribed by and onto the artist’s own body, highlighting a collision between different temporalities.

On the other hand, his character in the performance ‘Yog Raj Chitrakar visits Lal Chowk’ (2007) is inspired by his grandfather. This man, who studied painting in England in the 1930s, used to paint landscapes of Kashmir - the place he was native of and which became inaccessible to him and his family after 1989, when the separatist movement began to gain ground. His large paintings, which adorned the walls of Nikhil Chopra’s family home, were like windows on the past and a way for him to travel mentally beyond the limits set by politics. For this performance, he goes to Srinagar, the summer capital of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir : if the political pressures are lower nowadays, the police presence is still very strong. The performance starts with Chopra’s ritual of transformation (clothing, doing his hair, putting on make-up), before he starts walking around the city. Once arrived in Lal Chowk, a central neighborhood of the city, a crowd quickly gathers up around him while he starts drawing on the floor with charcoal and chalk. Against his first intention, what was meant to be a simple act - drawing - is turned into a political public act of resistance : the crowd, quickly controled by the police authorities, won’t be dissuaded from seeing the performance till the end. By a ritual and intimate constraint, Chopra revisits the colonial past and highlights the political transformations both present and future. Almost unintentionally, the autobiographical meets collective history ; the circle is complete.