Marcel van Eeden

09 May - 13 Jun 2009

MARCEL VAN EEDEN

Marcel van Eeden is considered a man of principles: since 1993, he has been reating a new drawing each day, which he then places on the Internet, allowing a diary of drawings to emerge on his website. The artist finds the motifs that serve as the basis for his drawings on walks through second-hand bookstores, archives, libraries, and flea markets. The fact that these newspapers, books, and hotographs—usually black and white reproductions—all come from the time before his birth on November 22, 1965 indicates van Eeden’s intense occupation with death and “non-existence”—everything here revolves around the time before he was born. Not the “no longer,” but the “not yet” is central to his drawings. In this way, hundreds of small format works have emerged which impressively nderscore the artist’s self-imposed guidelines, not least due to the repeated use of black/white contrasts and the usually standardized format of 14 x 19 cm or 19 x 28 cm.

While at the start of his career van Eeden tended to make individual drawings, in ecent years he has focused on series, where the components develop their impact on the beholder especially in combination with one another. The drawings from the series seem to be illustrations of a narrative that is partially based in historical acts and partially based in fiction. Like film stills, the almost photo-realistic images show figures and locations with a captivating urgency, figures and locations that are strangely still, and yet could come to life at any moment. By using black harcoal, van Eeden achieves the characteristic chiaroscuro effect in his work.

In an extensive series of drawings, the life of the botanist K.M. Wiegand becomes a fictional “biography of a swindler” (Johan Schloemann): as the artist puts it, the protagonist embodies for the beholder a kind of “superhero” whose adventures are followed by van Eeden’s pictures. Like the series The Archaeologist: The ravels of Oswald Sollmann, Celia, and The Death of Matheus Boryna, here the ndividual images of the series combine to form an overarching whole. The text assages that can be seen running across the images seem to be assigned a tructuring principle. The Dutch artist thus combines text and image so that text is rought into relation with the motifs, but the visual motifs seem to have no elationship to the events in the texts. In their arrangement, applied with stencils nd often integrated as a kind of caption or “speech bubble,” the texts exhibit their proximity to the world of comics. For the series Celia, the artist used passages rom T. S. Eliot’s Cocktail Party (1949) and Robert Walser’s Spaziergang (1917), hereby the selection of texts here is also based on the principle to not use anything created after 1965.

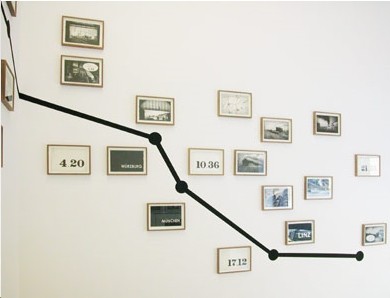

In the series on view at Georg Kargl BOX Last Trip to Vienna, the protagonist K.M. Wiegand undertakes a train trip from The Hague to Vienna in November 1948. As lready in the series Witness for the Prosecution, shown at Heidelberger unstverein, the series of drawings shown at BOX presents encounters among arious protagonists, this time with post-war Vienna as its dark setting. Exactly why Wiegand meets van Eeden’s earlier figures Matheus Boryna and Oswald Sollmann in a Vienna coffeehouse is left open. In terms of time setting, this meeting redates the Death of Matheus Boryna, where perhaps the tracks are laid for later crimes. An atmosphere of espionage and betrayal captures our breath, and still leaves us unclear about the precise connections between the various criminal acts. But it is apparent that everything in this installation at BOX— around 40 drawings, a video in which Van Eeden’s model for K. M. Wiegand speaks for himself, and a model train—are all closely connected to a new series around Boryna, Sollmann, and Wiegand. To be continued...

Marcel van Eeden is considered a man of principles: since 1993, he has been reating a new drawing each day, which he then places on the Internet, allowing a diary of drawings to emerge on his website. The artist finds the motifs that serve as the basis for his drawings on walks through second-hand bookstores, archives, libraries, and flea markets. The fact that these newspapers, books, and hotographs—usually black and white reproductions—all come from the time before his birth on November 22, 1965 indicates van Eeden’s intense occupation with death and “non-existence”—everything here revolves around the time before he was born. Not the “no longer,” but the “not yet” is central to his drawings. In this way, hundreds of small format works have emerged which impressively nderscore the artist’s self-imposed guidelines, not least due to the repeated use of black/white contrasts and the usually standardized format of 14 x 19 cm or 19 x 28 cm.

While at the start of his career van Eeden tended to make individual drawings, in ecent years he has focused on series, where the components develop their impact on the beholder especially in combination with one another. The drawings from the series seem to be illustrations of a narrative that is partially based in historical acts and partially based in fiction. Like film stills, the almost photo-realistic images show figures and locations with a captivating urgency, figures and locations that are strangely still, and yet could come to life at any moment. By using black harcoal, van Eeden achieves the characteristic chiaroscuro effect in his work.

In an extensive series of drawings, the life of the botanist K.M. Wiegand becomes a fictional “biography of a swindler” (Johan Schloemann): as the artist puts it, the protagonist embodies for the beholder a kind of “superhero” whose adventures are followed by van Eeden’s pictures. Like the series The Archaeologist: The ravels of Oswald Sollmann, Celia, and The Death of Matheus Boryna, here the ndividual images of the series combine to form an overarching whole. The text assages that can be seen running across the images seem to be assigned a tructuring principle. The Dutch artist thus combines text and image so that text is rought into relation with the motifs, but the visual motifs seem to have no elationship to the events in the texts. In their arrangement, applied with stencils nd often integrated as a kind of caption or “speech bubble,” the texts exhibit their proximity to the world of comics. For the series Celia, the artist used passages rom T. S. Eliot’s Cocktail Party (1949) and Robert Walser’s Spaziergang (1917), hereby the selection of texts here is also based on the principle to not use anything created after 1965.

In the series on view at Georg Kargl BOX Last Trip to Vienna, the protagonist K.M. Wiegand undertakes a train trip from The Hague to Vienna in November 1948. As lready in the series Witness for the Prosecution, shown at Heidelberger unstverein, the series of drawings shown at BOX presents encounters among arious protagonists, this time with post-war Vienna as its dark setting. Exactly why Wiegand meets van Eeden’s earlier figures Matheus Boryna and Oswald Sollmann in a Vienna coffeehouse is left open. In terms of time setting, this meeting redates the Death of Matheus Boryna, where perhaps the tracks are laid for later crimes. An atmosphere of espionage and betrayal captures our breath, and still leaves us unclear about the precise connections between the various criminal acts. But it is apparent that everything in this installation at BOX— around 40 drawings, a video in which Van Eeden’s model for K. M. Wiegand speaks for himself, and a model train—are all closely connected to a new series around Boryna, Sollmann, and Wiegand. To be continued...