Slavs and Tatars

Lektor

15 Nov 2014 - 01 Mar 2015

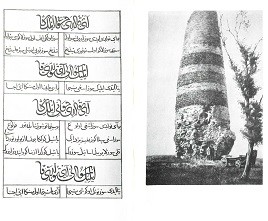

Slavs and Tatars, (Left): Karakhanid script from Yusuf Khass Hajib’s Kutadgu Bilig. (Right) Burana Tower from Khass Hajib's home town Balasagun in present-day Kyrgyzstan.

INFORM award winners 2013

Slavs and Tatars is a faction of polemics and intimacies devoted to an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia. The collective’s work spans several media, disciplines, and a broad spectrum of cultural registers (high and low) focusing on an oft-forgotten sphere of influence between Slavs, Caucasians and Central Asians. (www.slavsandtatars.com)

In their installation “Lektor” in the Credner Salon, the music room at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Slavs and Tatars examine the politics and performativity of language. The starting point of their four-channel audio installation is one of the most influential 11th-century Turkish mirrors for princes, the Kutadgu Bilig (Wisdom of Royal Glory).

Both in the Muslim and Christian traditions of the Middle Ages, mirrors for princes were a medium of political criticism in poetic form. Even though the focus of scientific interest at that time was on theological themes, mirrors for princes were a secular means of addressing the issues of sovereignty and rule. As a quasi educational medium, they conveyed critical perspectives and offered advice, especially in cases when a young and inexperienced king was about to come to power, being the next in the line of succession or having won a military victory.

The sections from Kutadgu Bilig selected by Slavs and Tatars for “Lektor” are all concerned with the use and performance of language as a means of exercising power; at the same time they demonstrate the immense range and performance potential of the texts found in mirrors for princes.

The historical text is translated into Turkish, Polish and German and spoken aloud in the room, constantly superimposed with the original Uighur language. In this way, “Lektor” brings the original message into line with the cultural field of tension “to the east of the former Berlin Wall and to the west of the Great Wall of China”, opening it up for current debates on (neo)colonisation, identity, language and geopolitics, and on the relationship between past and present, as well as between language, text and translation.

Slavs and Tatars is a faction of polemics and intimacies devoted to an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia. The collective’s work spans several media, disciplines, and a broad spectrum of cultural registers (high and low) focusing on an oft-forgotten sphere of influence between Slavs, Caucasians and Central Asians. (www.slavsandtatars.com)

In their installation “Lektor” in the Credner Salon, the music room at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Slavs and Tatars examine the politics and performativity of language. The starting point of their four-channel audio installation is one of the most influential 11th-century Turkish mirrors for princes, the Kutadgu Bilig (Wisdom of Royal Glory).

Both in the Muslim and Christian traditions of the Middle Ages, mirrors for princes were a medium of political criticism in poetic form. Even though the focus of scientific interest at that time was on theological themes, mirrors for princes were a secular means of addressing the issues of sovereignty and rule. As a quasi educational medium, they conveyed critical perspectives and offered advice, especially in cases when a young and inexperienced king was about to come to power, being the next in the line of succession or having won a military victory.

The sections from Kutadgu Bilig selected by Slavs and Tatars for “Lektor” are all concerned with the use and performance of language as a means of exercising power; at the same time they demonstrate the immense range and performance potential of the texts found in mirrors for princes.

The historical text is translated into Turkish, Polish and German and spoken aloud in the room, constantly superimposed with the original Uighur language. In this way, “Lektor” brings the original message into line with the cultural field of tension “to the east of the former Berlin Wall and to the west of the Great Wall of China”, opening it up for current debates on (neo)colonisation, identity, language and geopolitics, and on the relationship between past and present, as well as between language, text and translation.