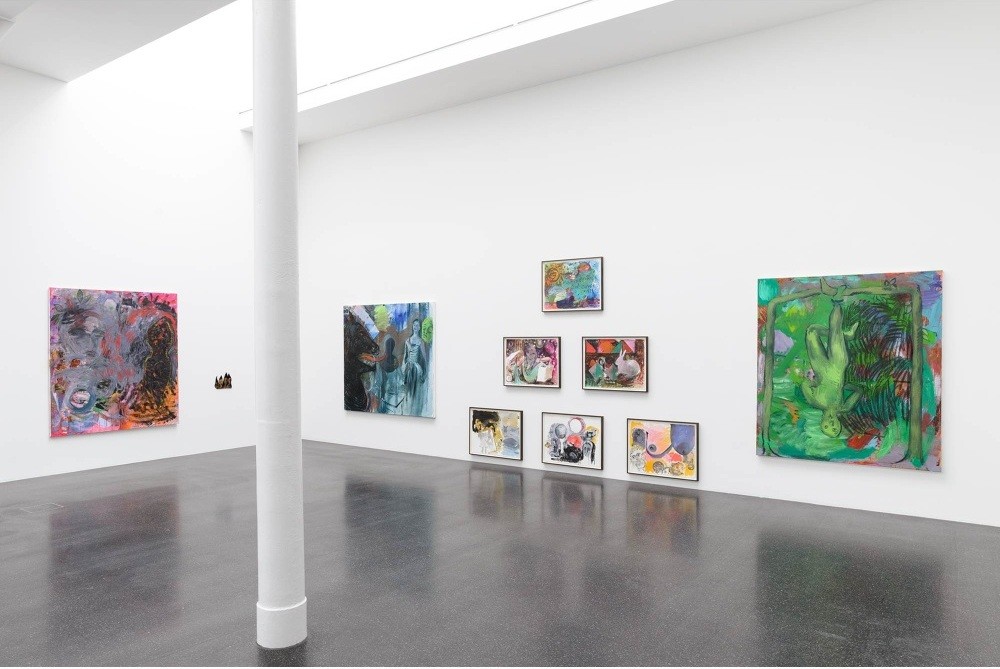

Lucy Stein

Knockers

03 Mar - 14 Apr 2018

LUCY STEIN

Knockers

3 March - 14 April 2018

Text by Penny Florence, Professor Emerita at The Slade School of Fine Art, University College London.

The Morphogenesis of Modernism: Stein and the Sexed Universal

Knockers, this timely new show from Lucy Stein serendipitously coincides with her inclusion in the Virginia Woolf-inspired group show at Tate St Ives. The Tate show deserves to prove a game-changer, since it subtly demonstrates the breadth and quality of art by women from the rise of Modernism to the present. It does this by using Woolf’s writing as a philosophical and thematic underpinning - and by leaving it to the viewer to realise that no art by men is represented. Both are highly instructive. Overall, the curation shifts how we understand the ground we thought we knew.

Stein’s role in the Tate show’s voyage of discovery is considerable. Not only are her pieces powerful as presences, they connect many of the painterly developments in ways that are rarely, if ever, acknowledged in the narratives of Modernism. There is a simultaneous exploration in her work of abstract expressionism, surrealism, myth and feminism, for example. This brings to attention that the whole show is also making new connections between innovation, traditions, movements and styles. It is a reinvention of painterly language and it strongly challenges the usefulness of most of those “-isms” I’ve just used.

I like to call this overall process ”morphogenesis” because it derives from material science, bringing together origin and form as dynamic: origin is always already in motion; form is indispensable to movement. Nothing is fixed yet everything is related. Relationality is a mass of changing tensions and releases but it is grounded. This is a language, not of disembodied symbolism, but that speaks the body

It is essential to bear this embodied language in mind when approaching Stein’s latest work. What is behind the surface is in continuous conversation with what is on it.

Take Con Leche (2018) - the reference to esoteric symbolism (top left) is clear enough. But you’d be mistaken to think its presence signifies you have arrived at either a starting-point or an end. Top right and, although similar shapes emerge, they are now more abstract, with the red and black ground thinning to grey and yellow. Between and below and behind the rest of the canvas, light blues cool the heat of what could become a vortex, were it not balanced by the rhythmic holding power of the central body, an outlined negative space whose forms converse with the symbols and the multiple layered surfaces. A similar, more diffuse mingling of bodies and landscape is extended yet further in Bee Cumming at Boscawen-Un (2016), where bodies are integrated into its mobile layering.

This common materiality of bodies and the natural world manifests again in Green Man Hanging (2018). While his foot is a point of attachment to the tree, it is also a way into and through it, and the branch to the left of the foot is like another foot. The man’s stance is impossible; the tree’s square framing growth equally so. The leaves, lines and marks of the dark area on the right suggest a seahorse or perhaps a dragon, uniting all forms as animate.

Yet this suggestion of commonality is not a merging. It never settles into a unified or decorative surface. An essential part of the lexicon in Stein’s recent work is the appearance of triangular shapes, often arranged in oblongs, as in Con Leche. What are they? the object of the goddess-like figure’s gaze, or a signal of something else?

These geometries are a constant reminder of other dimensions as we also see in Celtic Ultrasound and Petrified Maidens. Originating in the tiles of 16th Century Valencia, and associated by Stein with spatial simplification, they act in a number of ways as punctuation or rhythmic anchoring, or palette/palate cleansers. I might compare the effect of the river of milky tears, solidifying yet spectral, that participates in and stabilises Con Leche’s gorgeous dance. Yet none of these elements is ultimately explicable, and nor should they be. They remain mysterious disturbances, to trip the complacent.

Plunge into this exhilaration of potential energy, and any idea of a single meaning or direction seems irrelevant. We have moved through the esoteric to other places that invest the “now” with the vibrancy of all time and space. If that isn’t magic, then what is?

This is the territory of Bee Cumming at Boscawen-Un (2016), a painting that rewards different ways of looking. It invokes what Stein calls “a blissful embodied moment”, comparing it to the syncretic experience of blinking your eyes in the bright light of summer. Despite its ambiguities and smudginess, it is clear at a level that manifests if you go with its dedifferentiated vision and yield to the strange potency it conveys of ancient sites that connect to the greater forces of the cosmos. As with Agnes Martin, a good place to start is very close up, where peripheral vision becomes more important to seeing than it generally is in singular, directed focus.

Yet, interestingly, what Stein is thinking about when she paints is technical. Thinking about the different handling of paint while still working on Celtic Ultrasound (2018), Stein remarked that just then she was interested in the upper part where she had scraped paint from other paintings and worked it in with a palette knife, and then with bringing this together with the contrastingly limpid areas. Her interest was in ways of revealing how disparate surfaces could work together.

Perhaps it’s the technical approach of the alchemist, since it is focussed on the transformative potential of the material. These tiles, at the same as they work formally as described above, operate on the elemental level of intense, fiery heat, the firing of clay like the base metal in a crucible. Stein’s interest in embodiment extends to the materiality of painting, the interaction of the physicality of hand and pigment and support.

This is an example of the way Stein regards painting as a difficult process of problem solving, directed towards enabling the emergence of techniques, images or colours. It is not about conveying something that already exists, either in the interior or in the exterior world.

An aspect of this that I find fascinating is that she sees as symbolic the relations that emerge between materials and mark making, even (in Celtic Ultrasound) to the extent of responding to the cross struts of the stretcher behind the canvas as integral to the bones of the skeletal form under which it lies. It’s a subtle point, about the creation of an order of meaning somewhere between the Kristevan Imaginary and Symbolic - but without taking that theoretical frame too far.

This brings us to the reasons why I think this work signals the morphogenesis of Modernism into a way of painting broad enough to work with feminine and with the Subaltern. It is assimilation of a kind, but not passive incorporation into unchanged paradigm.

Understanding how female embodiment qualifies the paradigm of Modernism requires the metamorphosis of both - and it matters that the phrase is “female embodiment”, not “the female body”. This difference inflects all aspects of how we understand the issues. The same goes for the broader idea of the Subaltern on which received Modernism to an extent depends.

Celtic Ultrasound, like all the works in this show, was made during Stein’s first pregnancy. While these paintings do not at all depend on pregnancy, this knowledge enables a great deal for the viewer. For among the shifts this work effects is that of how we understand the integrity of the pregnant body as a universal, not only as a particular of reproduction or any feminine essentialism, but rather as morphogenesis.

But in raising that fact that these works were made during pregnancy, it is vital that we do not assume they are about it. Rather, this awareness is a gateway to expanding our fragmented grasp of creative history to embrace our common humanity.

It was an indispensable part of the idealism of Modernism that it should aspire to the universal. This aspect of the long and multifaceted art of the last Century has been under sustained attack since the early 60s catapulted it into later phases, and in some respects rightly so. But the work then was to break open, to oppose, to counter culture.

That work is now more subtle and complex. It is no longer dualist or oppositional. What art is now doing is to reinvent connection while maintaining differentials. Figuration is not opposed to abstraction; mainstream is not opposed to alternative.

In this light, the universal cannot be the singular domain it once seemed to be. It has to be a multiplicity of both-ands, a thousand tiny sexes and thousand micro-subjectivities that yet interact and pass through each other. In this, we are all able to participate in a universal that is a meeting, a position through which we might pass, not one that can be occupied. Yet difference remains. It is a sexed universal.

So this is a universal that embraces embodiment in its essentials. The only symbol of that, as Luce Irigaray has suggested, is the navel, the mark of umbilical connection carried by us all, newborn to urban spaceman.

References

Elizabeth Grosz (1990/1994) ‘A Thousand Tiny Sexes: Feminism and Rhizomatics’ in Boundas & Olkowski (eds) Gilles Deleuze and the Theater of Philosophy, Routledge. London/NY.

Julia Kristeva (1984) Revolution in Poetic Language. Columbia. NY.

Luce Irigaray (1980/1993) ‘Body against Body: In relation to the Mother’ in Sexes and Genealogies. Columbia. NY.

Knockers

3 March - 14 April 2018

Text by Penny Florence, Professor Emerita at The Slade School of Fine Art, University College London.

The Morphogenesis of Modernism: Stein and the Sexed Universal

Knockers, this timely new show from Lucy Stein serendipitously coincides with her inclusion in the Virginia Woolf-inspired group show at Tate St Ives. The Tate show deserves to prove a game-changer, since it subtly demonstrates the breadth and quality of art by women from the rise of Modernism to the present. It does this by using Woolf’s writing as a philosophical and thematic underpinning - and by leaving it to the viewer to realise that no art by men is represented. Both are highly instructive. Overall, the curation shifts how we understand the ground we thought we knew.

Stein’s role in the Tate show’s voyage of discovery is considerable. Not only are her pieces powerful as presences, they connect many of the painterly developments in ways that are rarely, if ever, acknowledged in the narratives of Modernism. There is a simultaneous exploration in her work of abstract expressionism, surrealism, myth and feminism, for example. This brings to attention that the whole show is also making new connections between innovation, traditions, movements and styles. It is a reinvention of painterly language and it strongly challenges the usefulness of most of those “-isms” I’ve just used.

I like to call this overall process ”morphogenesis” because it derives from material science, bringing together origin and form as dynamic: origin is always already in motion; form is indispensable to movement. Nothing is fixed yet everything is related. Relationality is a mass of changing tensions and releases but it is grounded. This is a language, not of disembodied symbolism, but that speaks the body

It is essential to bear this embodied language in mind when approaching Stein’s latest work. What is behind the surface is in continuous conversation with what is on it.

Take Con Leche (2018) - the reference to esoteric symbolism (top left) is clear enough. But you’d be mistaken to think its presence signifies you have arrived at either a starting-point or an end. Top right and, although similar shapes emerge, they are now more abstract, with the red and black ground thinning to grey and yellow. Between and below and behind the rest of the canvas, light blues cool the heat of what could become a vortex, were it not balanced by the rhythmic holding power of the central body, an outlined negative space whose forms converse with the symbols and the multiple layered surfaces. A similar, more diffuse mingling of bodies and landscape is extended yet further in Bee Cumming at Boscawen-Un (2016), where bodies are integrated into its mobile layering.

This common materiality of bodies and the natural world manifests again in Green Man Hanging (2018). While his foot is a point of attachment to the tree, it is also a way into and through it, and the branch to the left of the foot is like another foot. The man’s stance is impossible; the tree’s square framing growth equally so. The leaves, lines and marks of the dark area on the right suggest a seahorse or perhaps a dragon, uniting all forms as animate.

Yet this suggestion of commonality is not a merging. It never settles into a unified or decorative surface. An essential part of the lexicon in Stein’s recent work is the appearance of triangular shapes, often arranged in oblongs, as in Con Leche. What are they? the object of the goddess-like figure’s gaze, or a signal of something else?

These geometries are a constant reminder of other dimensions as we also see in Celtic Ultrasound and Petrified Maidens. Originating in the tiles of 16th Century Valencia, and associated by Stein with spatial simplification, they act in a number of ways as punctuation or rhythmic anchoring, or palette/palate cleansers. I might compare the effect of the river of milky tears, solidifying yet spectral, that participates in and stabilises Con Leche’s gorgeous dance. Yet none of these elements is ultimately explicable, and nor should they be. They remain mysterious disturbances, to trip the complacent.

Plunge into this exhilaration of potential energy, and any idea of a single meaning or direction seems irrelevant. We have moved through the esoteric to other places that invest the “now” with the vibrancy of all time and space. If that isn’t magic, then what is?

This is the territory of Bee Cumming at Boscawen-Un (2016), a painting that rewards different ways of looking. It invokes what Stein calls “a blissful embodied moment”, comparing it to the syncretic experience of blinking your eyes in the bright light of summer. Despite its ambiguities and smudginess, it is clear at a level that manifests if you go with its dedifferentiated vision and yield to the strange potency it conveys of ancient sites that connect to the greater forces of the cosmos. As with Agnes Martin, a good place to start is very close up, where peripheral vision becomes more important to seeing than it generally is in singular, directed focus.

Yet, interestingly, what Stein is thinking about when she paints is technical. Thinking about the different handling of paint while still working on Celtic Ultrasound (2018), Stein remarked that just then she was interested in the upper part where she had scraped paint from other paintings and worked it in with a palette knife, and then with bringing this together with the contrastingly limpid areas. Her interest was in ways of revealing how disparate surfaces could work together.

Perhaps it’s the technical approach of the alchemist, since it is focussed on the transformative potential of the material. These tiles, at the same as they work formally as described above, operate on the elemental level of intense, fiery heat, the firing of clay like the base metal in a crucible. Stein’s interest in embodiment extends to the materiality of painting, the interaction of the physicality of hand and pigment and support.

This is an example of the way Stein regards painting as a difficult process of problem solving, directed towards enabling the emergence of techniques, images or colours. It is not about conveying something that already exists, either in the interior or in the exterior world.

An aspect of this that I find fascinating is that she sees as symbolic the relations that emerge between materials and mark making, even (in Celtic Ultrasound) to the extent of responding to the cross struts of the stretcher behind the canvas as integral to the bones of the skeletal form under which it lies. It’s a subtle point, about the creation of an order of meaning somewhere between the Kristevan Imaginary and Symbolic - but without taking that theoretical frame too far.

This brings us to the reasons why I think this work signals the morphogenesis of Modernism into a way of painting broad enough to work with feminine and with the Subaltern. It is assimilation of a kind, but not passive incorporation into unchanged paradigm.

Understanding how female embodiment qualifies the paradigm of Modernism requires the metamorphosis of both - and it matters that the phrase is “female embodiment”, not “the female body”. This difference inflects all aspects of how we understand the issues. The same goes for the broader idea of the Subaltern on which received Modernism to an extent depends.

Celtic Ultrasound, like all the works in this show, was made during Stein’s first pregnancy. While these paintings do not at all depend on pregnancy, this knowledge enables a great deal for the viewer. For among the shifts this work effects is that of how we understand the integrity of the pregnant body as a universal, not only as a particular of reproduction or any feminine essentialism, but rather as morphogenesis.

But in raising that fact that these works were made during pregnancy, it is vital that we do not assume they are about it. Rather, this awareness is a gateway to expanding our fragmented grasp of creative history to embrace our common humanity.

It was an indispensable part of the idealism of Modernism that it should aspire to the universal. This aspect of the long and multifaceted art of the last Century has been under sustained attack since the early 60s catapulted it into later phases, and in some respects rightly so. But the work then was to break open, to oppose, to counter culture.

That work is now more subtle and complex. It is no longer dualist or oppositional. What art is now doing is to reinvent connection while maintaining differentials. Figuration is not opposed to abstraction; mainstream is not opposed to alternative.

In this light, the universal cannot be the singular domain it once seemed to be. It has to be a multiplicity of both-ands, a thousand tiny sexes and thousand micro-subjectivities that yet interact and pass through each other. In this, we are all able to participate in a universal that is a meeting, a position through which we might pass, not one that can be occupied. Yet difference remains. It is a sexed universal.

So this is a universal that embraces embodiment in its essentials. The only symbol of that, as Luce Irigaray has suggested, is the navel, the mark of umbilical connection carried by us all, newborn to urban spaceman.

References

Elizabeth Grosz (1990/1994) ‘A Thousand Tiny Sexes: Feminism and Rhizomatics’ in Boundas & Olkowski (eds) Gilles Deleuze and the Theater of Philosophy, Routledge. London/NY.

Julia Kristeva (1984) Revolution in Poetic Language. Columbia. NY.

Luce Irigaray (1980/1993) ‘Body against Body: In relation to the Mother’ in Sexes and Genealogies. Columbia. NY.