Anni Albers

Touching Vision

06 Oct 2017 - 14 Jan 2018

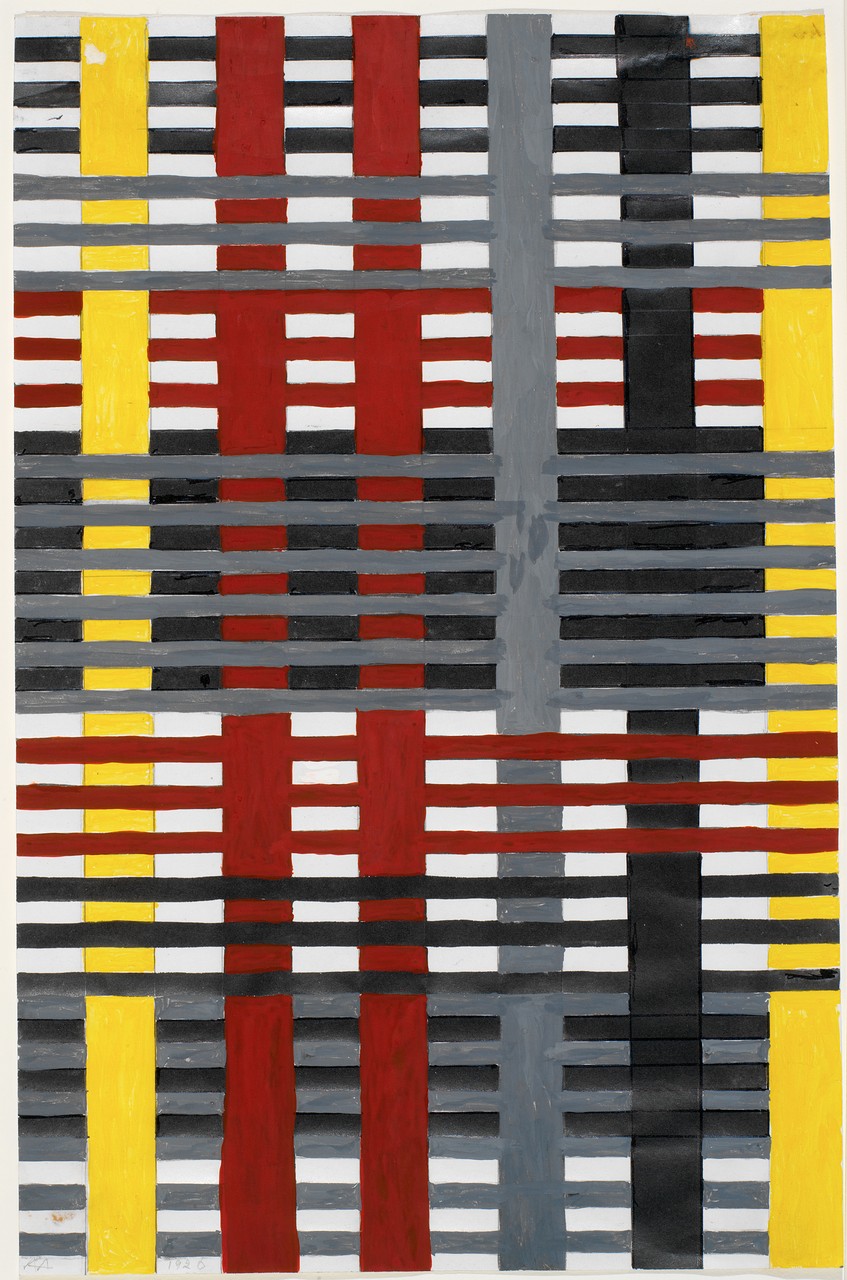

Anni Albers, Wallhanging, 1924, Cotton and silk, 168.3 × 100.3 cm

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

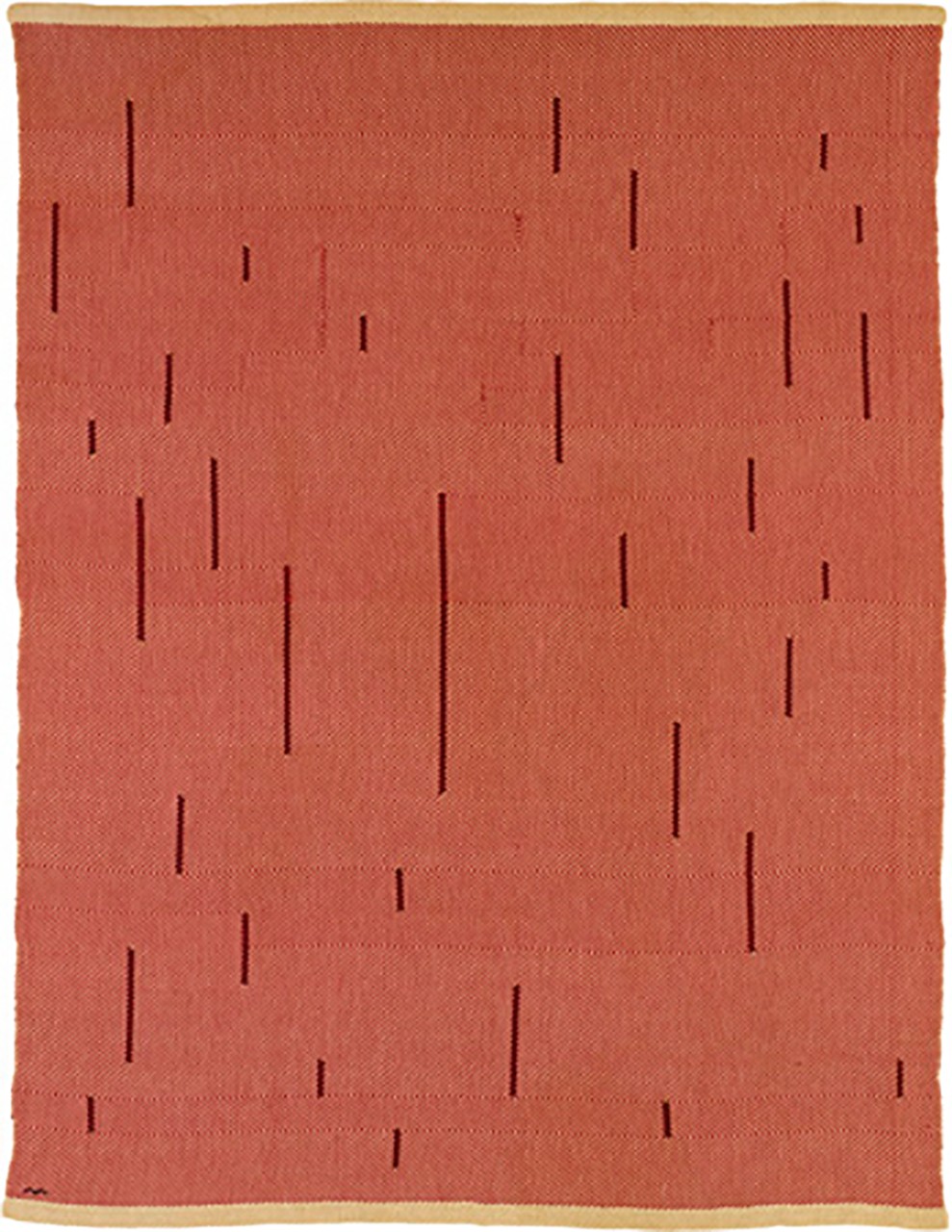

Anni Albers , With Verticals, 1946, Cotton and linen, 154.9 × 118.1 cm

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

Anni Albers , La Luz I, 1947, Linen and metallic thread, 47 × 82.5 cm

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

Anni Albers, Study for Unexecuted Wall Hanging, n.d., Gouache on paper, 38 x 24.8 cm

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

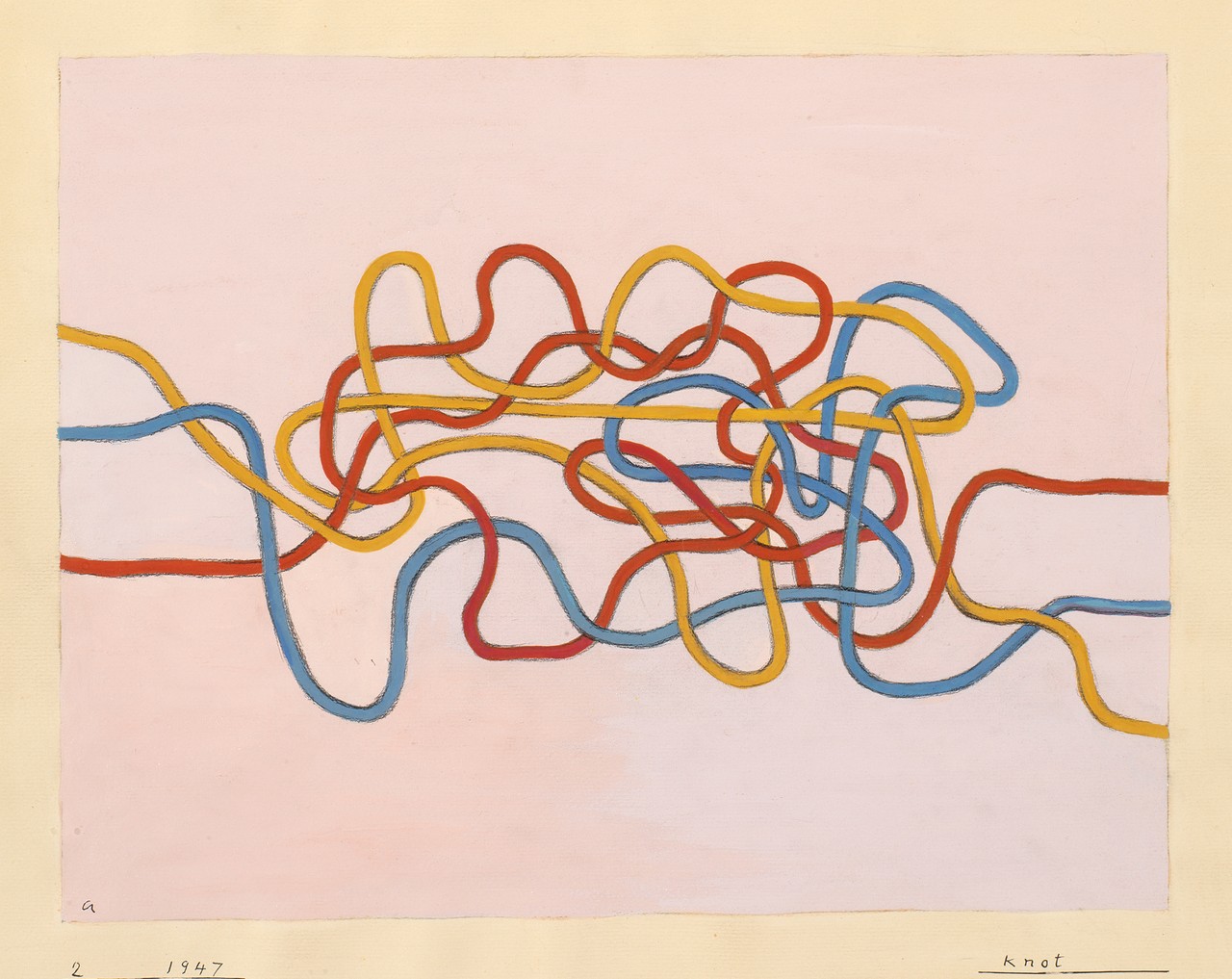

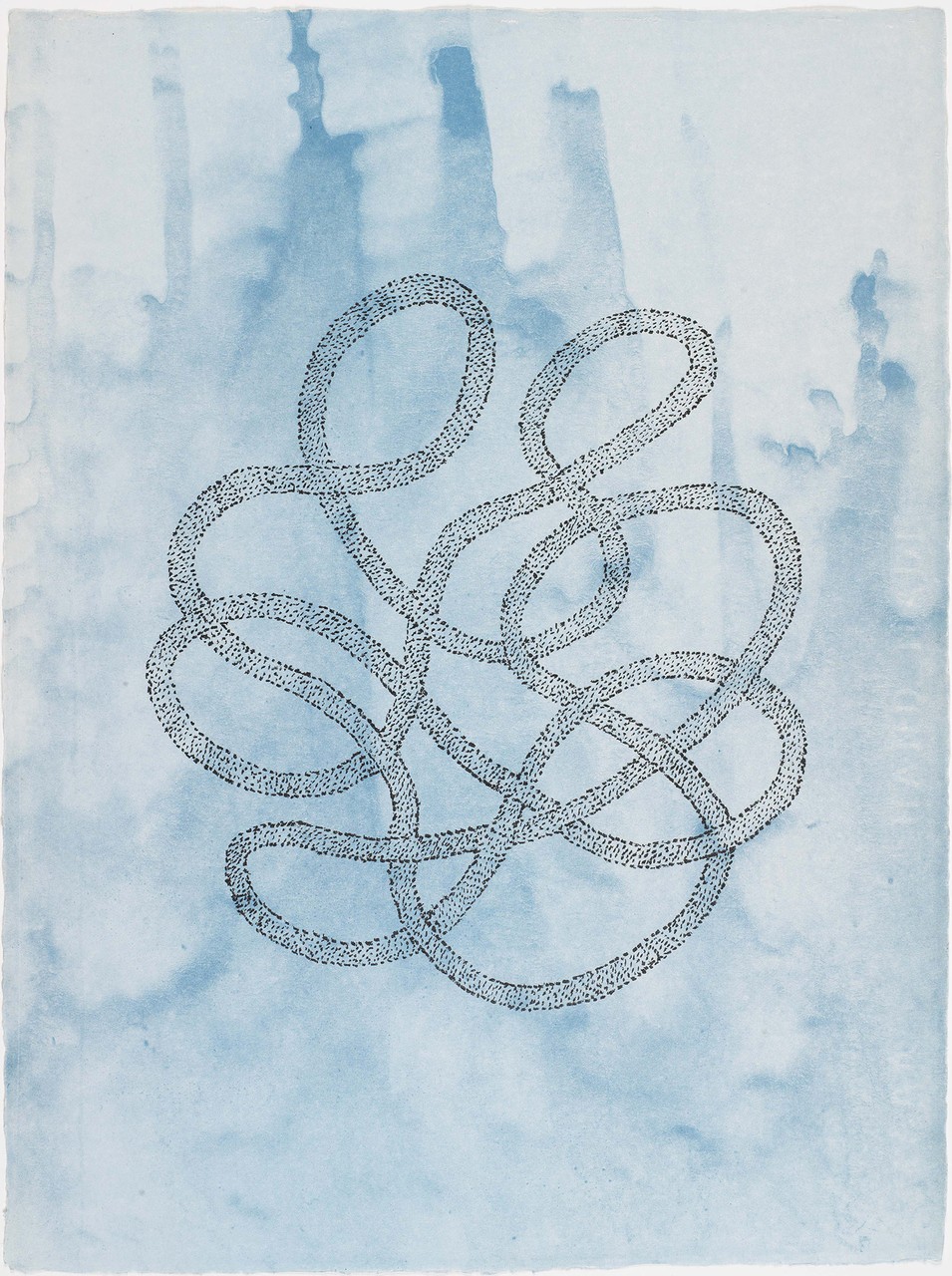

Anni Albers , Knot, 1947, Gouache on paper, 43.2 × 51 cm

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

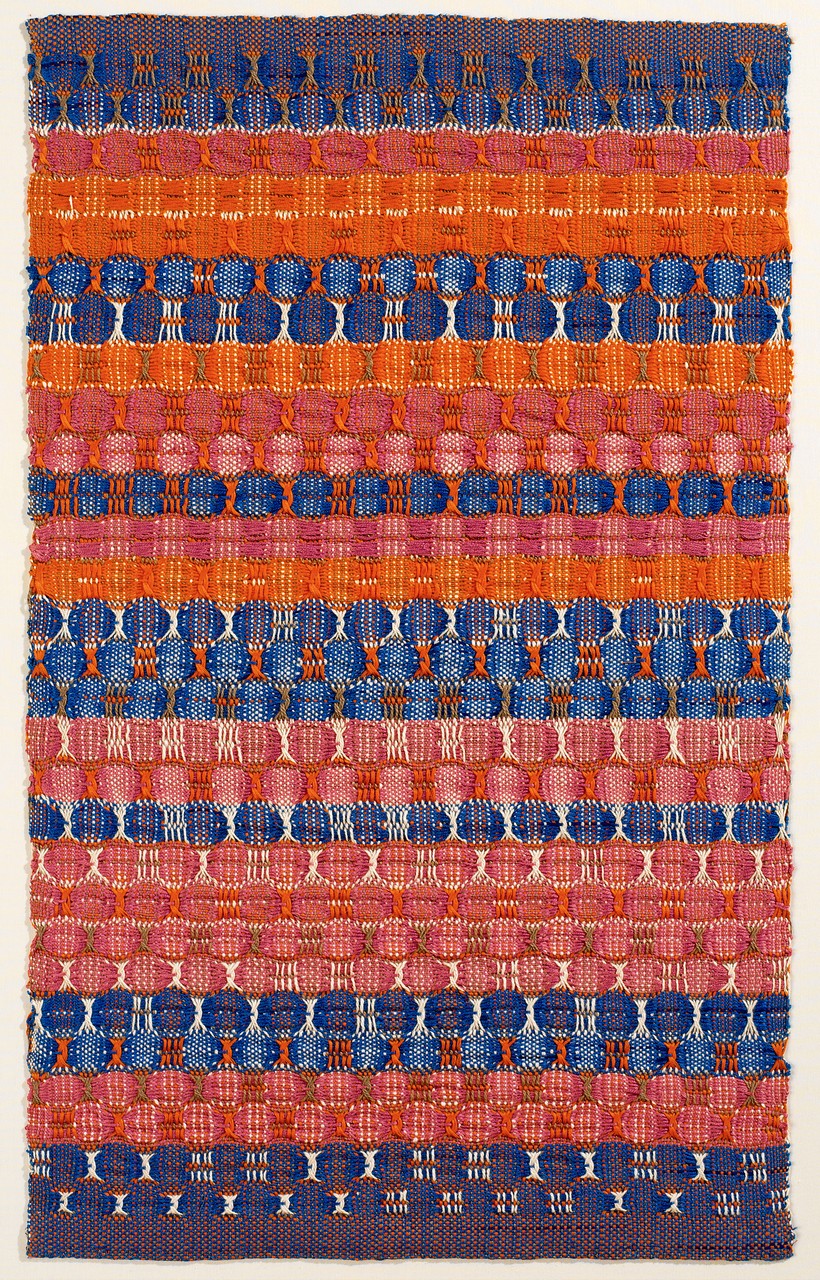

Anni Albers , Red and Blue Layers, 1958, Pictorial weaving, 61.6 x 37.8 cm

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

Anni Albers, Untitled, 1963, Lithograph, 46.7 x 62.2 cm

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

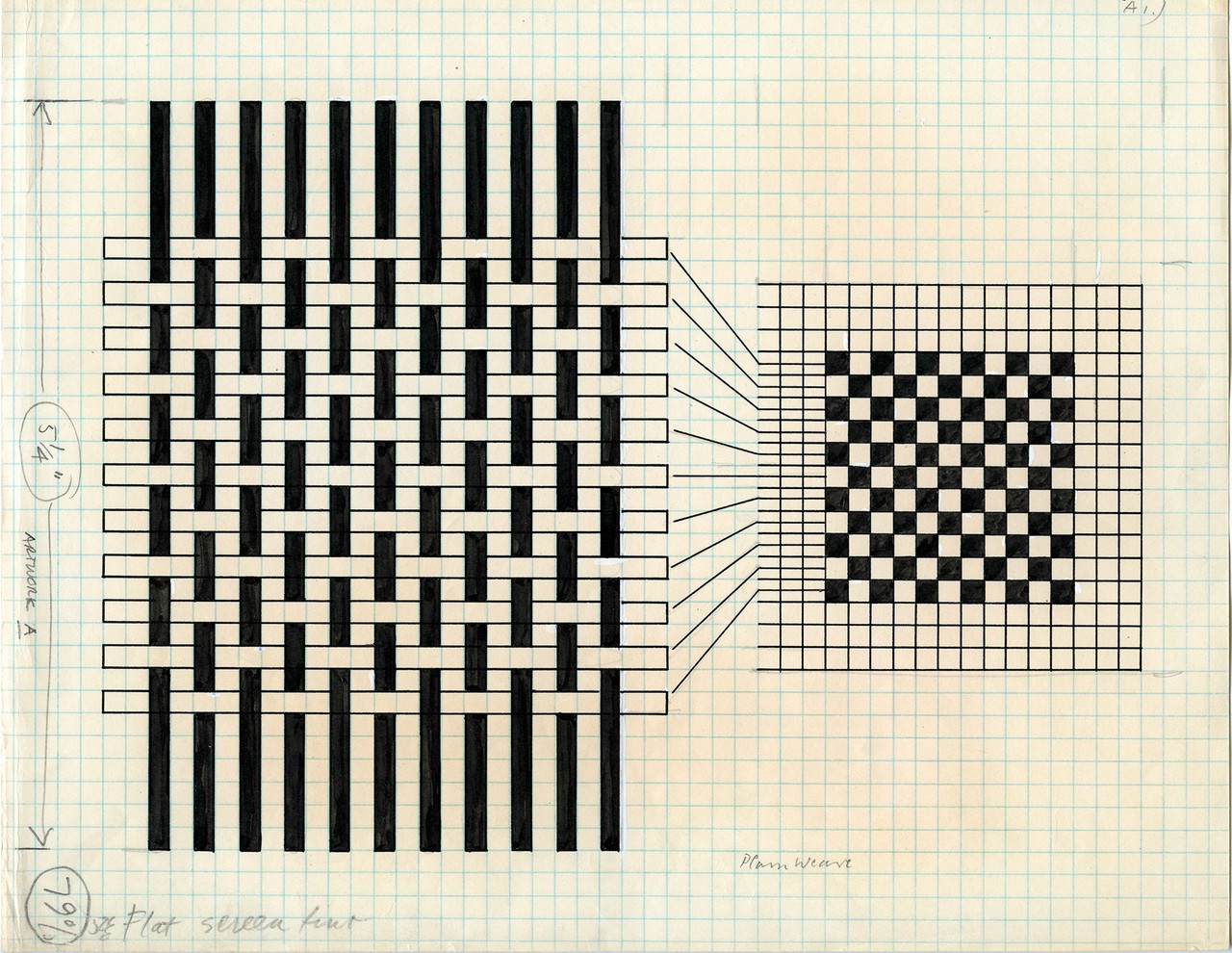

Anni Albers , Diagram showing draft notation (plain weave), Plate 10 from On Weaving, 1965, Ink on pencil on gridded paper, 27.8 x 21.6 cm

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT

Photo: Tim Nighdwander/Imaging4Art

©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

ANNI ALBERS

Touching Vision

6 October 2017 – 14 January 2018

Courtesy of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany, Connecticut.

Best known for her pioneering role in the field of textile or fiber art, her innovative treatment of warp and weft, and her constant quest for new patterns and uses of fabric, Anni Albers (b. 1899, Berlin; d. 1994, Orange, CT) was instrumental in redefining the artist as a designer. Her art was inspired by pre-Columbian folklore and modern industry, yet unhampered by conventional notions of craftsmanship and gender-specific labor. Albers studied at the Bauhaus in Weimar, where she met her husband, the painter Josef Albers, and eventually directed the weaving workshop in 1931. After the institution was closed by the Nazi party in 1933, Albers and her husband moved to North Carolina, where they were both hired to teach at a free-form school that would become a benchmark of modern American art, Black Mountain College. There Anni Albers continued to combine her educational activity with artistic experimentation, while also authoring what are now considered seminal texts in the history of contemporary textile art. The exhibition Anni Albers: Touching Vision is an in-depth survey of her most important series between 1925 and the late 1970s. The formal associations between works and series produced over the years will reveal affinities and unifying threads that illustrate the influence and continued relevance of this unique artist’s ideas.

FORM-PRODUCTION AND EXPERIMENTATION

In 1922, Anni Albers joined the Bauhaus school of Weimar, an avant-garde institution where she would also meet her husband, the painter Josef Albers. A hard-working student and gifted weaver, she went on to assist professor Gunta Stölzl and served as acting director of the weaving workshop several times between 1929 and 1931. When the Bauhaus was closed by the Nazi party in 1933, Albers and her husband moved to North Carolina, USA, where they both took over as teachers at a recently-created free school named Black Mountain College, which was to become a landmark for North American modernism.

This section shows work from both periods, during which Albers’s creative thinking underwent a decisive development. The present selection of Bauhaus works includes preparatory drawings for textiles (some of them executed or replicated decades later, or even posthumously) as well as numerous examples of her research into simple, functional textiles. In the meantime, the pieces created during the 1940s show the liberating effect of experimentation within the artistic community at Black Mountain, where previous rationalist conceptions welcomed an unexpected, intuitive lyricism. It was during this decade that Albers coined the term “pictorial weaving” to refer to the tapestries she hand-wove on the loom. On the formal level, it can be observed how the predominantly orthogonal patterns of her beginnings transitioned toward freer motifs and a direct dialogue between texture and color, sometimes evoking spiritual visions or imaginary landscapes. The selection of works from this period is complemented by selected works announcing Albers’s development in the early 1950s, and a section that documents her inspiring journeys to Latin America with Josef, including ancient textiles acquired then and kept in their personal collection.

TEXT AND TEXTILE: FOLLOWING THE THREAD

Albers’s presence on the vibrant American scene was a key factor in her emotional opening to new forms and new practices, and in the consolidation of a singular approach to weaving. By 1949, Albers’s reputation was definitively established by a large solo exhibition organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, followed by an extensive tour through museums of the United States. After the Alberses left Black Mountain College for the New Haven area in Connecticut, where they would live for the rest of their lives, Anni continued to combine artistic experimentation and occasional teaching work, while at the same time she produced some of the foundational writings of modern Fiber Art. This part of the exhibition presents a selection of her mature pictorial weavings, where new graphic motifs emerge to evoke ancient writing and suggest a purely rhythmical reading. These are hybrids of text and textile, of the canvas and the page, united on a support consisting entirely of warp and weft. Albers continued to develop this pattern until she stopped hand weaving in 1968.

At the same time, the artist started to rethink the role of preparatory drawings and gouaches for her fabrics, and her experiments with graphic techniques led her to produce, in 1964, her first important series of prints in the form of a portfolio titled Line Involvements. In printing work and its associated techniques, Albers found a new space for visual investigation that would eventually replace her textile work completely. On display together with this early graphic series is a selection of sketches, diagrams and photographs associated with the artist’s theoretical development, whose main expression was the book On Weaving, published in 1965.

REFLECTION AND DISTRIBUTION: THE GRAPHIC TERRITORY

Through aquatints, lithographs, silkscreen and offset prints, Albers was able to explore by other means some of the visual concepts that had already appeared in her textile pieces. Her playful experimentations with various chemical processes of engraving ran parallel to her collaboration with some of the finest printers of her time. Albers thus found a means for reflecting on the whole of her earlier oeuvre, as shown by the Connections portfolio, where she offered a concise synopsis of the great visual landmarks of nearly six decades of practice.

In printing, Albers found the ideal element for trying out new compositional patterns and almost infinite visual variations. Seeking higher levels of graphic complexity that reveal structural connections of lines and threads, of drawing and weaving, she multiplied triangular and rhomboid patterns. These forms alternate with the study of intricate lines evoking mazes, knots, and tangled threads in other works. Her designs are often times translated into textile models for large-scale production in collaboration with contemporary manufacturers—a practice whose continuity the artist ensured through the activities of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. Through her collaborations with the industry, Albers wanted to situate her work within reach of the public at large, and so demonstrated her commitment to the perennial idea of the Bauhaus that art and design are to be considered as one single field of form-production, and that prototypes should be developed to permit an egalitarian dissemination of artistic forms. The parallelism between the industrialization of the textile product and the graphic object, the possibility of democratizing the artwork, and an implicit critique of creative individualism, all come to the fore during this final period of Albers’s oeuvre.

Touching Vision

6 October 2017 – 14 January 2018

Courtesy of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany, Connecticut.

Best known for her pioneering role in the field of textile or fiber art, her innovative treatment of warp and weft, and her constant quest for new patterns and uses of fabric, Anni Albers (b. 1899, Berlin; d. 1994, Orange, CT) was instrumental in redefining the artist as a designer. Her art was inspired by pre-Columbian folklore and modern industry, yet unhampered by conventional notions of craftsmanship and gender-specific labor. Albers studied at the Bauhaus in Weimar, where she met her husband, the painter Josef Albers, and eventually directed the weaving workshop in 1931. After the institution was closed by the Nazi party in 1933, Albers and her husband moved to North Carolina, where they were both hired to teach at a free-form school that would become a benchmark of modern American art, Black Mountain College. There Anni Albers continued to combine her educational activity with artistic experimentation, while also authoring what are now considered seminal texts in the history of contemporary textile art. The exhibition Anni Albers: Touching Vision is an in-depth survey of her most important series between 1925 and the late 1970s. The formal associations between works and series produced over the years will reveal affinities and unifying threads that illustrate the influence and continued relevance of this unique artist’s ideas.

FORM-PRODUCTION AND EXPERIMENTATION

In 1922, Anni Albers joined the Bauhaus school of Weimar, an avant-garde institution where she would also meet her husband, the painter Josef Albers. A hard-working student and gifted weaver, she went on to assist professor Gunta Stölzl and served as acting director of the weaving workshop several times between 1929 and 1931. When the Bauhaus was closed by the Nazi party in 1933, Albers and her husband moved to North Carolina, USA, where they both took over as teachers at a recently-created free school named Black Mountain College, which was to become a landmark for North American modernism.

This section shows work from both periods, during which Albers’s creative thinking underwent a decisive development. The present selection of Bauhaus works includes preparatory drawings for textiles (some of them executed or replicated decades later, or even posthumously) as well as numerous examples of her research into simple, functional textiles. In the meantime, the pieces created during the 1940s show the liberating effect of experimentation within the artistic community at Black Mountain, where previous rationalist conceptions welcomed an unexpected, intuitive lyricism. It was during this decade that Albers coined the term “pictorial weaving” to refer to the tapestries she hand-wove on the loom. On the formal level, it can be observed how the predominantly orthogonal patterns of her beginnings transitioned toward freer motifs and a direct dialogue between texture and color, sometimes evoking spiritual visions or imaginary landscapes. The selection of works from this period is complemented by selected works announcing Albers’s development in the early 1950s, and a section that documents her inspiring journeys to Latin America with Josef, including ancient textiles acquired then and kept in their personal collection.

TEXT AND TEXTILE: FOLLOWING THE THREAD

Albers’s presence on the vibrant American scene was a key factor in her emotional opening to new forms and new practices, and in the consolidation of a singular approach to weaving. By 1949, Albers’s reputation was definitively established by a large solo exhibition organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, followed by an extensive tour through museums of the United States. After the Alberses left Black Mountain College for the New Haven area in Connecticut, where they would live for the rest of their lives, Anni continued to combine artistic experimentation and occasional teaching work, while at the same time she produced some of the foundational writings of modern Fiber Art. This part of the exhibition presents a selection of her mature pictorial weavings, where new graphic motifs emerge to evoke ancient writing and suggest a purely rhythmical reading. These are hybrids of text and textile, of the canvas and the page, united on a support consisting entirely of warp and weft. Albers continued to develop this pattern until she stopped hand weaving in 1968.

At the same time, the artist started to rethink the role of preparatory drawings and gouaches for her fabrics, and her experiments with graphic techniques led her to produce, in 1964, her first important series of prints in the form of a portfolio titled Line Involvements. In printing work and its associated techniques, Albers found a new space for visual investigation that would eventually replace her textile work completely. On display together with this early graphic series is a selection of sketches, diagrams and photographs associated with the artist’s theoretical development, whose main expression was the book On Weaving, published in 1965.

REFLECTION AND DISTRIBUTION: THE GRAPHIC TERRITORY

Through aquatints, lithographs, silkscreen and offset prints, Albers was able to explore by other means some of the visual concepts that had already appeared in her textile pieces. Her playful experimentations with various chemical processes of engraving ran parallel to her collaboration with some of the finest printers of her time. Albers thus found a means for reflecting on the whole of her earlier oeuvre, as shown by the Connections portfolio, where she offered a concise synopsis of the great visual landmarks of nearly six decades of practice.

In printing, Albers found the ideal element for trying out new compositional patterns and almost infinite visual variations. Seeking higher levels of graphic complexity that reveal structural connections of lines and threads, of drawing and weaving, she multiplied triangular and rhomboid patterns. These forms alternate with the study of intricate lines evoking mazes, knots, and tangled threads in other works. Her designs are often times translated into textile models for large-scale production in collaboration with contemporary manufacturers—a practice whose continuity the artist ensured through the activities of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. Through her collaborations with the industry, Albers wanted to situate her work within reach of the public at large, and so demonstrated her commitment to the perennial idea of the Bauhaus that art and design are to be considered as one single field of form-production, and that prototypes should be developed to permit an egalitarian dissemination of artistic forms. The parallelism between the industrialization of the textile product and the graphic object, the possibility of democratizing the artwork, and an implicit critique of creative individualism, all come to the fore during this final period of Albers’s oeuvre.