Agnieszka Polska

The Demon’s Brain

27 Sep 2018 - 03 Mar 2019

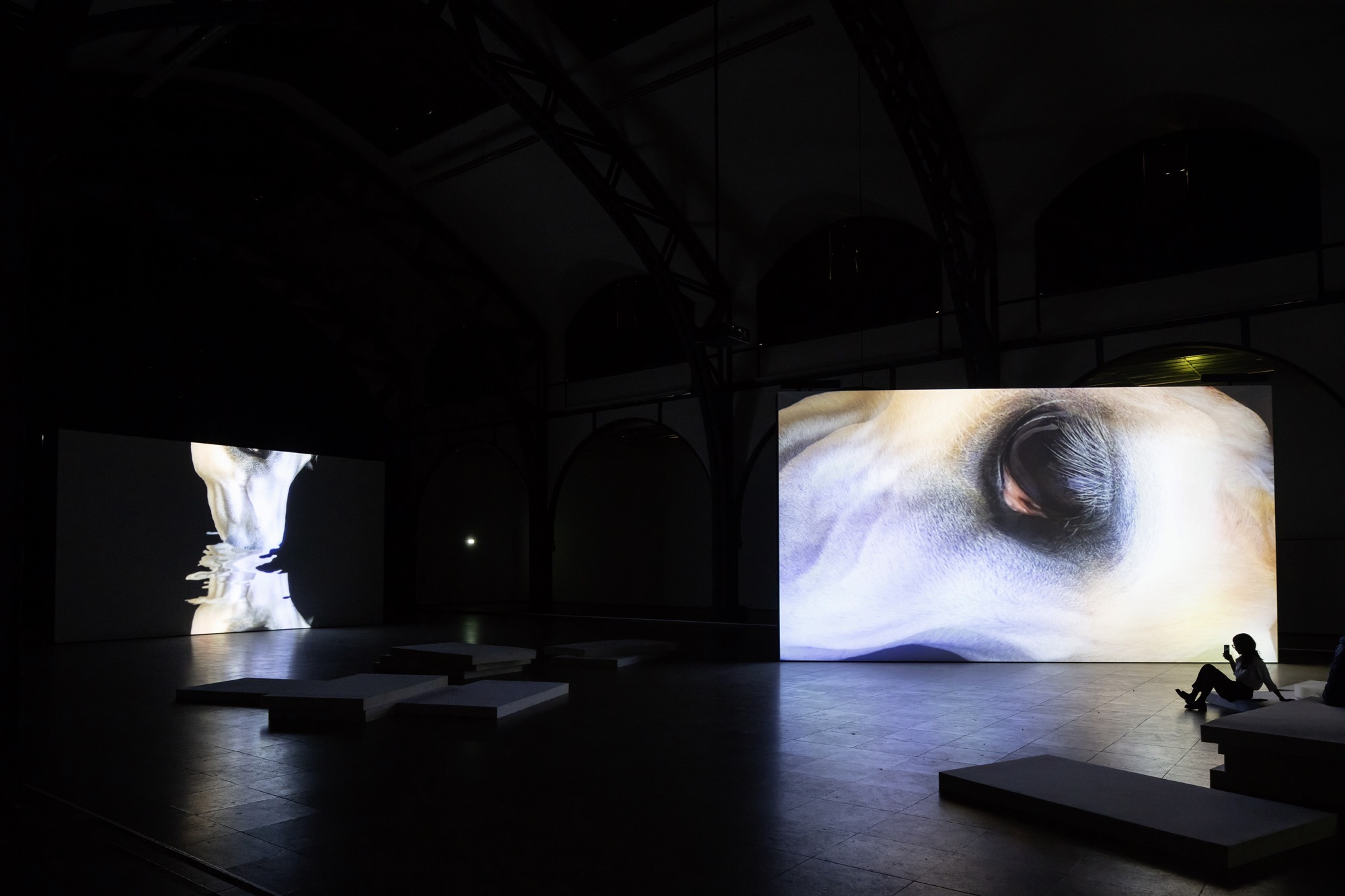

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018. Installation view at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2019 © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018. Installation view at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2019 © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018. Installation view at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2019 © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018. Installation view at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2019 © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018. Installation view at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2019 © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018

© Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

© Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

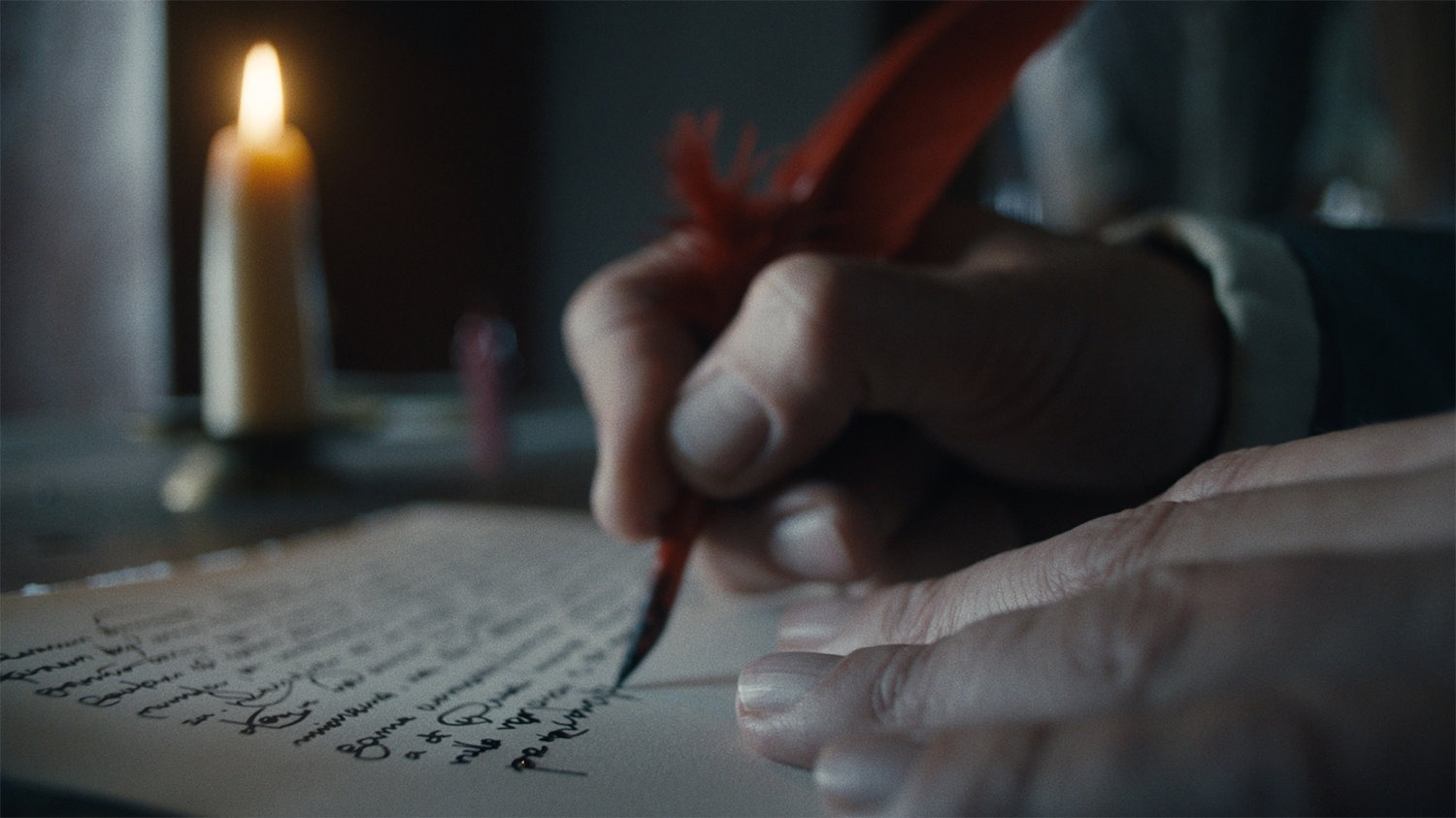

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018. Multichannel video installation, film still

© Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

© Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018. Multichannel video installation, film still

© Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

© Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018. Multichannel video installation, film still

© Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

© Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018. Multichannel video installation, film still

© Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

© Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy Żak | Branicka, Berlin and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles

Agnieszka Polska: The Demon’s Brain

27.09.2018 to 03.03.2019

Hamburger Bahnhof - Museum für Gegenwart - Berlin

In The Demon’s Brain, a multichannel video installation created expressly for the exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin, Agnieszka Polska grapples with the ethical question of how individuals can assume social responsibility amid the overwhelming demands of the present moment. The point of departure for the work is a collection of fifteenth-century letters addressed to Mikołaj Serafin, the custodian of Poland’s salt mines. In her videos, Polska melds live action with animation to tell the fictional story of a young messenger tasked with delivering these letters on horseback. Along the way, the boy loses his horse and he gets lost in the forest. There he has an unexpected encounter with a demon, whose monologue fuses Christian theological ideas with today’s developments concerning resource consumption, environmental destruction, data capital, and artificial intelligence.

During the period in which the story is set, salt was a valuable commodity and an important source of wealth for the Kingdom of Poland. The extraction of the mineral was made possible by a unique agreement whereby King Władysław III (1424–1444) entrusted the supervision of the mines to Serafin, who ran them from 1434 to 1459 as an independent, proto-capitalist enterprise within the prevailing feudal order. The organization relied mainly on wage labor, was financed by venture capital, and produced predominantly for a market that it attempted to control. The salt was mined through a complex division of labor akin to modern production processes. It was only with the support of a network of creditors and debtors that Serafin was able to keep the precarious operation running. The letters, written in Latin, attest to the rapid growth of the salt mines but also to the heavy toll exacted on human and natural resources. An ailing and discontented peasantry in the surrounding area, unsustainable deforestation, and the constant threat of plague are just some of the problems revealed in the correspondence.

The installation The Demon’s Brain, conceived for the museum’s Historical Hall, consists of four large-format projection screens and a wall of texts. The films show various scenes, which run in an endless loop but are synchronized so that they comment on each other. A low-pitched, subliminal rhythm additionally unites the scenes, helping to bridge gaps in time. After the demon has explained to the messenger how he himself can change the course of history, his recurring proclamation “It is not too late” reverberates through the hall, becoming an urgent appeal to the viewer.

In The Demon’s Brain Agnieszka Polska explores the possibilities for individuals to take personal action and assume responsibility for the problems facing the world. Although the messenger seems to heed the demon’s entreaty, we are forced to realize from today’s perspective that he was evidently unable to change things. Can individual action in fact have any influence on the complex processes in the world around us, and how do we decide which actions to take? Who can we trust to help us make this decision?

The wall of texts suggests a way out of this impasse. Excerpts from the historical letters to Serafin are interspersed with commentaries on the economic, ecological, and technological issues addressed in the work, taken from essays commissioned for the accompanying catalogue. The capacity of subjects to make a difference is thus juxtaposed with descriptions of abstract processes. What is revealed here is that active involvement, reflection, and exchanges with others, as well as the recognition of long-term patterns, can be the first steps to overcoming the ostensible powerlessness and ineffectiveness of the individual in the face of seemingly insurmountable crises.

Last year Agnieszka Polska (b. 1985 in Lublin, Poland, lives in Berlin) was the recipient of the ninth biennial Preis der Nationalgalerie. The jury consisted of Zdenka Badovinac, director of the Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, Hou Hanru, artistic director of the MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Rome, Sheena Wagstaff, Leonard A. Lauder Chairman for Modern and Contemporary Art of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Sven Beckstette, curator at Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin, and Udo Kittelmann, director of the Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. This solo exhibition and an accompanying publication are part of the award.

To accompany the exhibition a catalogue will be published in December by Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König. Edited by Udo Kittelmann and Sven Beckstette, with texts by Sven Beckstette, Federica Bueti, Nora N. Khan, Margarida Mendes, Matteo Pasquinelli, Jan Sowa, Tiziana Terranova.

27.09.2018 to 03.03.2019

Hamburger Bahnhof - Museum für Gegenwart - Berlin

In The Demon’s Brain, a multichannel video installation created expressly for the exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin, Agnieszka Polska grapples with the ethical question of how individuals can assume social responsibility amid the overwhelming demands of the present moment. The point of departure for the work is a collection of fifteenth-century letters addressed to Mikołaj Serafin, the custodian of Poland’s salt mines. In her videos, Polska melds live action with animation to tell the fictional story of a young messenger tasked with delivering these letters on horseback. Along the way, the boy loses his horse and he gets lost in the forest. There he has an unexpected encounter with a demon, whose monologue fuses Christian theological ideas with today’s developments concerning resource consumption, environmental destruction, data capital, and artificial intelligence.

During the period in which the story is set, salt was a valuable commodity and an important source of wealth for the Kingdom of Poland. The extraction of the mineral was made possible by a unique agreement whereby King Władysław III (1424–1444) entrusted the supervision of the mines to Serafin, who ran them from 1434 to 1459 as an independent, proto-capitalist enterprise within the prevailing feudal order. The organization relied mainly on wage labor, was financed by venture capital, and produced predominantly for a market that it attempted to control. The salt was mined through a complex division of labor akin to modern production processes. It was only with the support of a network of creditors and debtors that Serafin was able to keep the precarious operation running. The letters, written in Latin, attest to the rapid growth of the salt mines but also to the heavy toll exacted on human and natural resources. An ailing and discontented peasantry in the surrounding area, unsustainable deforestation, and the constant threat of plague are just some of the problems revealed in the correspondence.

The installation The Demon’s Brain, conceived for the museum’s Historical Hall, consists of four large-format projection screens and a wall of texts. The films show various scenes, which run in an endless loop but are synchronized so that they comment on each other. A low-pitched, subliminal rhythm additionally unites the scenes, helping to bridge gaps in time. After the demon has explained to the messenger how he himself can change the course of history, his recurring proclamation “It is not too late” reverberates through the hall, becoming an urgent appeal to the viewer.

In The Demon’s Brain Agnieszka Polska explores the possibilities for individuals to take personal action and assume responsibility for the problems facing the world. Although the messenger seems to heed the demon’s entreaty, we are forced to realize from today’s perspective that he was evidently unable to change things. Can individual action in fact have any influence on the complex processes in the world around us, and how do we decide which actions to take? Who can we trust to help us make this decision?

The wall of texts suggests a way out of this impasse. Excerpts from the historical letters to Serafin are interspersed with commentaries on the economic, ecological, and technological issues addressed in the work, taken from essays commissioned for the accompanying catalogue. The capacity of subjects to make a difference is thus juxtaposed with descriptions of abstract processes. What is revealed here is that active involvement, reflection, and exchanges with others, as well as the recognition of long-term patterns, can be the first steps to overcoming the ostensible powerlessness and ineffectiveness of the individual in the face of seemingly insurmountable crises.

Last year Agnieszka Polska (b. 1985 in Lublin, Poland, lives in Berlin) was the recipient of the ninth biennial Preis der Nationalgalerie. The jury consisted of Zdenka Badovinac, director of the Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, Hou Hanru, artistic director of the MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Rome, Sheena Wagstaff, Leonard A. Lauder Chairman for Modern and Contemporary Art of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Sven Beckstette, curator at Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin, and Udo Kittelmann, director of the Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. This solo exhibition and an accompanying publication are part of the award.

To accompany the exhibition a catalogue will be published in December by Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König. Edited by Udo Kittelmann and Sven Beckstette, with texts by Sven Beckstette, Federica Bueti, Nora N. Khan, Margarida Mendes, Matteo Pasquinelli, Jan Sowa, Tiziana Terranova.