Ali Cherri

14 Feb - 28 May 2017

Ali Cherri

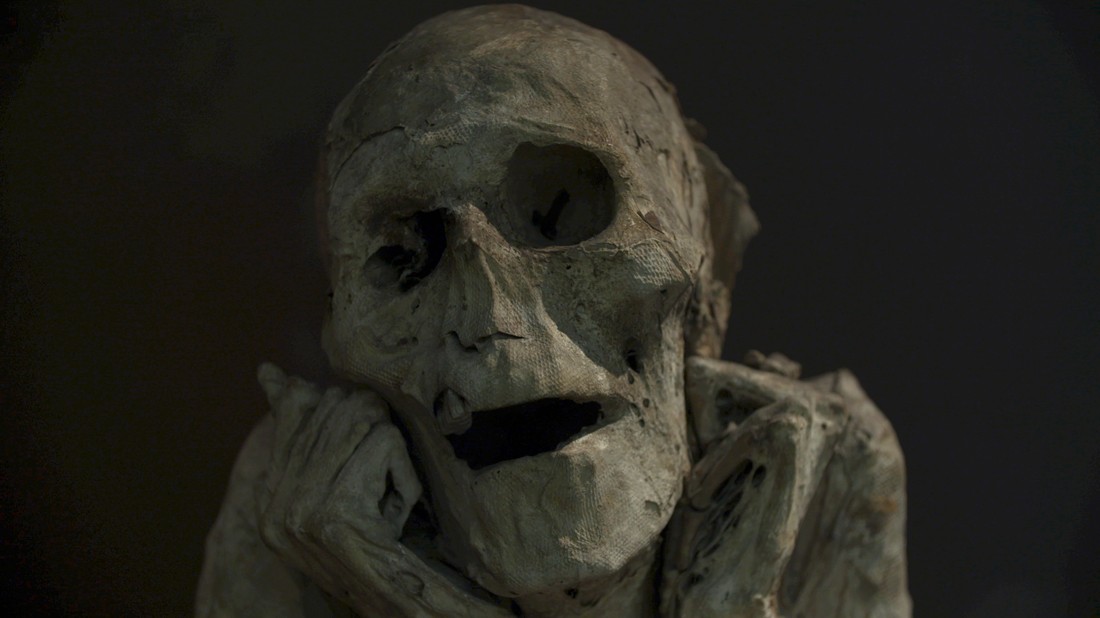

Somniculus, 2017

Photographie de tournage, courtesy de l'artiste. Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

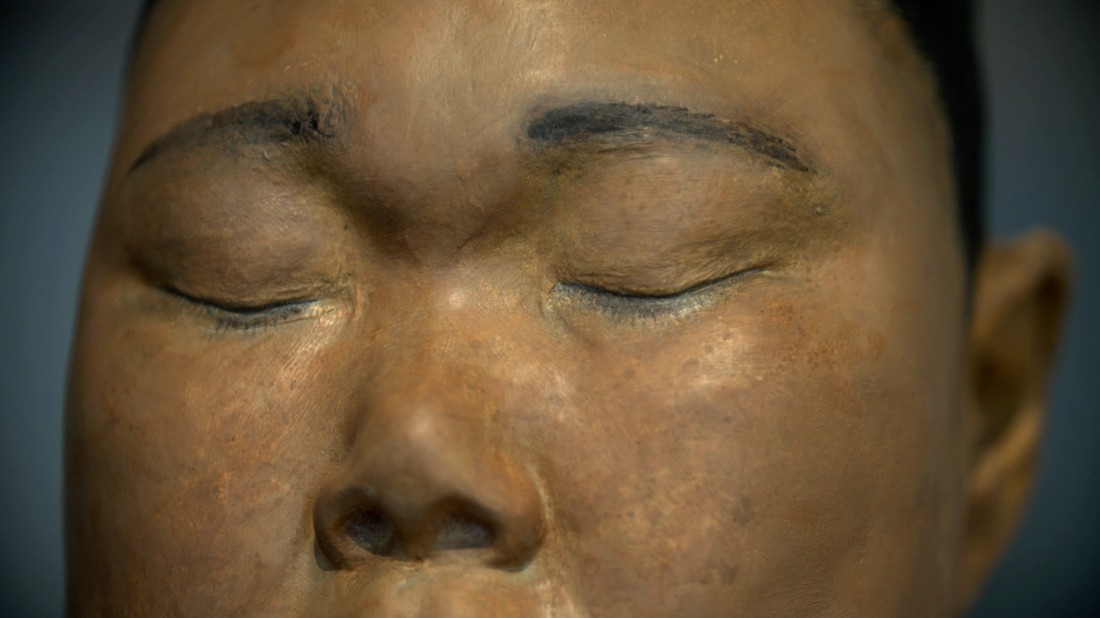

Somniculus, 2017

Photographie de tournage, courtesy de l'artiste. Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

Ali Cherri

Somniculus, 2017

Vidéo HD, courtesy de l'artiste. Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

Somniculus, 2017

Vidéo HD, courtesy de l'artiste. Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

Ali Cherri

Somniculus, 2017

Vidéo HD, courtesy de l'artiste. Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

Somniculus, 2017

Vidéo HD, courtesy de l'artiste. Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

Ali Cherri

Somniculus, 2017

Vidéo HD, courtesy de l'artiste. Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

Somniculus, 2017

Vidéo HD, courtesy de l'artiste. Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

Ali Cherri

Somniculus, 2017

Vidéo HD, courtesy de l'artiste. Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

Somniculus, 2017

Vidéo HD, courtesy de l'artiste. Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

ALI CHERRI

Somniculus

14 February - 28 May 2017

Curator: Osei Bonsu

Ali Cherri is a video and visual artist. His current project looks at the place of the archaeological object in the construction of historical narratives. In recent years, he has unearthed systems of archaeological preservation, exploring the history of ruins and cartography in the context of the Middle East and North Africa’s pre- and post-colonial histories.

Filmed inside a series of empty museum galleries across Paris, Ali Cherri’s Somniculus (the Latin word for “light sleep”) articulates the tension between the lives of dead objects and the living world that surrounds them. Artefacts from museums of ethnography, archaeology and natural sciences are all presented in their existing cultural context as the surviving objects of human interest. Preserved inside this structure of historiographic display, each object is representative of a place or a time and each artefact lives on as a container of its own history. What if we suspended these objects outside this constructed framework of controlled meaning? Would their ideological value become any less tangible?

As a result of periods of Enlightenment, imperialism and colonial expansion over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, museums in Paris became some of the world’s most encyclopaedic institutions. The trajectory of the modern museum, from the cabinet of curiosities to a nationalist project to the colonial institution, and on to the neoliberal structure of the present day, reflects the shifting ideologies of our civilization. In Somniculus, the viewer is presented with a series of windows through which the objects in the museum escape these ideological regimes altogether. We see how these objects might relate to us in a pre-modern sense, as objects endowed with their own autonomy and agency.

Although the modern era has given rise to a divide between the living and the non-living, human and nonhuman, culture and nature, the project of existing museum practice seeks to bring objects of the past to life by reactivating historical narratives. Forming a discontinuity, the mummified bodies from ancient Egypt, taxidermy wildlife and fragments of non-European cultures found in Somniculus seem less than alive, yet they speak to us and haunt us still, as if to transcend their contained existence. The objects no longer represent a coherent representational universe, defined by ordering and classification, but rather the beginning of another fiction.

Though it would seem that the modern museum is a space of the object rather than the subject, the human body has played an integral role in the construction of our world as we know it. While the evolution of man is often defined by anthropological and anatomical developments in science, our physical relationship to objects in museums is often one of passive detachment. We are reminded that the idea of looking is not a political act of questioning the reality before us, but a way of probing the origin of the gaze itself. A camera lingers over torch-lit objects whose eyes shine back at us, while other objects lack the ability to see altogether — their view is that of an abyss or a black whole. Is it the lack of sight that prevents them from seeing, or the absence of eyes?

The apparent necessity of seeing, the act of closing and opening the eyes, recalls the inevitability of sleep and its inescapable shadow: death. Shining a light on these spaces of perpetual significance within Western culture, Somniculus brings a heightened awareness to the act of looking and seeing in the museum. As an anonymous man sleeps in an otherwise empty gallery we realise that he too is representative of a culture, a time, a place. These fragments of loss, destruction and violence stand in as representations of civilizations’ past. In accordance with the cultures they serve to represent, these objects are neither caught inside the deep dark past nor immediately visible in the light of our present day, but forever waiting to be awakened.

Osei Bonsu

Ali Cherri was born in 1976 in Beirut. He received a BA in graphic design from the American University in Beirut in 2000, and an MA in performing arts from DasArts, Amsterdam, in 2005. Cherri has participated in the exhibitions But a Storm Is Blowing from Paradise (Guggenheim New York, 2016), A Taxonomy of Fallacies: The Life of Dead Objects (solo exhibition, Sursock Museum, Beirut, 2016), Matérialité de l’Invisible (Centquatre, Paris, 2016), Time out of Joint (Sharjah Art Space, 2016), Earth and Ever After (Saudi Art Council, Jeddah, 2016), Desires and Necessities (MACBA, Spain, 2015), Lest the Two Seas Meet (Warsaw Museum of Modern Art, Poland, 2015), Mare Medi Terra (Es Baluard Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Palma, Spain, 2015) and Songs of Loss and Songs of Love (Gwangju Museum of Art, South Korea, 2014). Ali Cherri lives and works in Paris and Beirut.

Somniculus

14 February - 28 May 2017

Curator: Osei Bonsu

Ali Cherri is a video and visual artist. His current project looks at the place of the archaeological object in the construction of historical narratives. In recent years, he has unearthed systems of archaeological preservation, exploring the history of ruins and cartography in the context of the Middle East and North Africa’s pre- and post-colonial histories.

Filmed inside a series of empty museum galleries across Paris, Ali Cherri’s Somniculus (the Latin word for “light sleep”) articulates the tension between the lives of dead objects and the living world that surrounds them. Artefacts from museums of ethnography, archaeology and natural sciences are all presented in their existing cultural context as the surviving objects of human interest. Preserved inside this structure of historiographic display, each object is representative of a place or a time and each artefact lives on as a container of its own history. What if we suspended these objects outside this constructed framework of controlled meaning? Would their ideological value become any less tangible?

As a result of periods of Enlightenment, imperialism and colonial expansion over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, museums in Paris became some of the world’s most encyclopaedic institutions. The trajectory of the modern museum, from the cabinet of curiosities to a nationalist project to the colonial institution, and on to the neoliberal structure of the present day, reflects the shifting ideologies of our civilization. In Somniculus, the viewer is presented with a series of windows through which the objects in the museum escape these ideological regimes altogether. We see how these objects might relate to us in a pre-modern sense, as objects endowed with their own autonomy and agency.

Although the modern era has given rise to a divide between the living and the non-living, human and nonhuman, culture and nature, the project of existing museum practice seeks to bring objects of the past to life by reactivating historical narratives. Forming a discontinuity, the mummified bodies from ancient Egypt, taxidermy wildlife and fragments of non-European cultures found in Somniculus seem less than alive, yet they speak to us and haunt us still, as if to transcend their contained existence. The objects no longer represent a coherent representational universe, defined by ordering and classification, but rather the beginning of another fiction.

Though it would seem that the modern museum is a space of the object rather than the subject, the human body has played an integral role in the construction of our world as we know it. While the evolution of man is often defined by anthropological and anatomical developments in science, our physical relationship to objects in museums is often one of passive detachment. We are reminded that the idea of looking is not a political act of questioning the reality before us, but a way of probing the origin of the gaze itself. A camera lingers over torch-lit objects whose eyes shine back at us, while other objects lack the ability to see altogether — their view is that of an abyss or a black whole. Is it the lack of sight that prevents them from seeing, or the absence of eyes?

The apparent necessity of seeing, the act of closing and opening the eyes, recalls the inevitability of sleep and its inescapable shadow: death. Shining a light on these spaces of perpetual significance within Western culture, Somniculus brings a heightened awareness to the act of looking and seeing in the museum. As an anonymous man sleeps in an otherwise empty gallery we realise that he too is representative of a culture, a time, a place. These fragments of loss, destruction and violence stand in as representations of civilizations’ past. In accordance with the cultures they serve to represent, these objects are neither caught inside the deep dark past nor immediately visible in the light of our present day, but forever waiting to be awakened.

Osei Bonsu

Ali Cherri was born in 1976 in Beirut. He received a BA in graphic design from the American University in Beirut in 2000, and an MA in performing arts from DasArts, Amsterdam, in 2005. Cherri has participated in the exhibitions But a Storm Is Blowing from Paradise (Guggenheim New York, 2016), A Taxonomy of Fallacies: The Life of Dead Objects (solo exhibition, Sursock Museum, Beirut, 2016), Matérialité de l’Invisible (Centquatre, Paris, 2016), Time out of Joint (Sharjah Art Space, 2016), Earth and Ever After (Saudi Art Council, Jeddah, 2016), Desires and Necessities (MACBA, Spain, 2015), Lest the Two Seas Meet (Warsaw Museum of Modern Art, Poland, 2015), Mare Medi Terra (Es Baluard Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Palma, Spain, 2015) and Songs of Loss and Songs of Love (Gwangju Museum of Art, South Korea, 2014). Ali Cherri lives and works in Paris and Beirut.