Edgardo Aragón

09 Feb - 22 May 2016

Edgardo Aragón

Mésoamérique : l'effet ouragan

Vidéo HD, couleur, son, et série de 10 cartes.

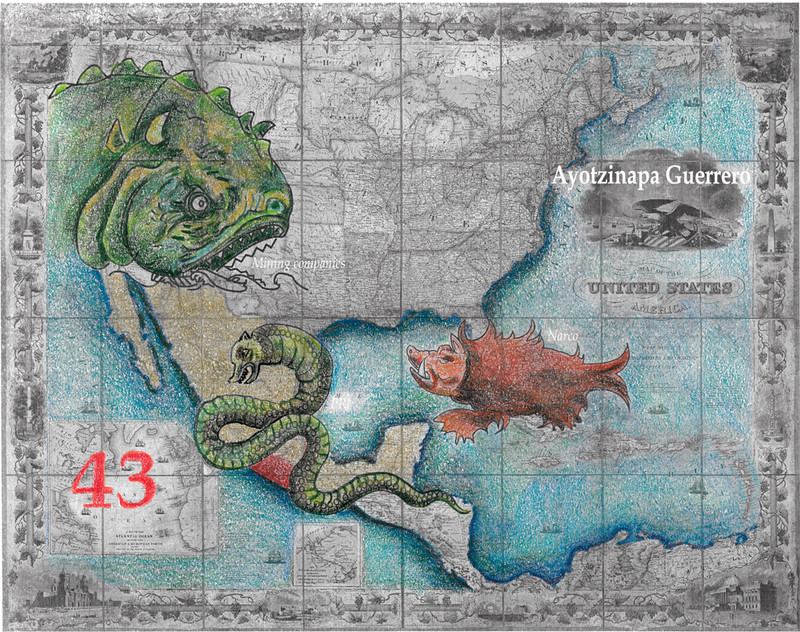

Carte représentant la disparition des 43 étudiants de l'université de Ayotzinapa dans l'État de Guerrero le 26 septembre 2014, et les parties impliquées.

Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

Mésoamérique : l'effet ouragan

Vidéo HD, couleur, son, et série de 10 cartes.

Carte représentant la disparition des 43 étudiants de l'université de Ayotzinapa dans l'État de Guerrero le 26 septembre 2014, et les parties impliquées.

Coproduction : Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation Nationale des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques et CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

EDGARDO ARAGÓN

Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect

9 February - 22 May 2016

Curator: Heidi Ballet

Mexican artist Edgardo Aragón addresses Mexican and global economic and political systems, and zooms in on their effects on Mexican communities.

In his new work, Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect, he provides a critical cartography that shows the power lines that define Mexico, the international Mesoamerica development project and its effects on the community of Cachimbo, located on a peninsula on the border between the states of Oaxaca and Chiapas.

In his work, Aragón often focuses on organised crime and conflict, sometimes re-enacting parts of his own family history that involved violence. His videos look deceptively calm, showing peaceful sunny landscapes, but as they unfold, details accumulate to tell very troubled stories about corrupt power relations. Aragón’s landscape portraits bring to mind “fukeiron”, the “landscape theory” developed by Japanese film-makers in the late 1960s, who put forward the idea that the landscapes one encounters in everyday life, even beautiful, postcard-like ones, are an expression of the dominant political powers. In the case of Aragón, the powers he represents in his work are drug cartels, political parties and foreign companies. He shows how their operations are intricately interlinked through corrupt deals.

Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect examines in close-up the effects of foreign power in Mexico today, which is reminiscent of the foreign control exerted many centuries ago. Mesoamerica was home to a rich civilization that emerged around 10,000 years BC and out of which grew the rich Maya, Aztec and Zapotec cultures, among many others. These cultures were destroyed by the Spanish, who arrived in the 15th and 16th centuries and used Christianity as a tool to discriminate against and subdue the locals. Today, “Mesoamerica” is also the short name for a multi-million dollar development project that is officially called the Mesoamerican Integration and Development Project and is financed and run by the United States. According to its official statement, the project is intended to help the region develop through investment in infrastructure, electricity, telecommunications and transport systems. However, due to rampant corruption at all levels, the project doesn’t benefit the poor communities and instead helps foreign companies that have holdings in the region.

In his video, Aragón zooms in on one particular place on the map of Mexico, namely the community of Cachimbo, which is located on a peninsula in the south, right on the border between the states of Oaxaca and Chiapas. Cachimbo is heavily hit by hurricanes and has to rebuild its infrastructure every year at the end of the hurricane season. It is also witnessing several types of illegal trade due to its border location. Although Cachimbo is very near one of the electricity plants that is part of the Mesoamerica Project, it has no electricity supply apart from a fragile solar energy system that was donated by an Indian NGO. The electricity generated by the wind turbines at the Mesoamerica Project energy plant is sent directly north, to the centre of Oaxaca, from where it is transferred to benefit the foreign-owned companies. In Aragón’s video, we see a protagonist carrying a battery from the centre of Oaxaca to Cachimbo. Aragón tries to correct the wrongs in the system of the Mesoamerica Project, and in a poetic gesture brings the electricity to the community where it should have gone to in the first place. The protagonist passes through the landscape, going past the wind turbines that were built as part of the Mesoamerica Project, and crossing the lake that leads to the peninsula. On arriving in Cachimbo, at the end of the video, the protagonist reads an excerpt from the book The Men Dispersed by the Dance by Andrés Henestrosa.

Andrés Henestrosa was a writer and politician who was born in the region where Cachimbo is located, and played an important role in preserving Zapotec culture from disappearance by collecting oral Zapotec legends and publishing them. The Men Dispersed by the Dance from 1929 is his most famous collection of Zapotec legends. The excerpt that the protagonist is reading in the video is a story in which the violent forces of nature are fighting each other and man is standing in the middle. After a catastrophe has taken place, a time of renewal arrives. Aragón chose this legend because it breaks with the Judeo-Christian tradition that Spanish colonialism left behind in the region and which forces people to accept fatal events and injustices – such as the consequences of the Mesoamerica Project – as destiny. He draws an analogy with the way that neoliberalism is globally accepted to be the only viable option today. Aragón re-inserts this legend into the Cachimbo community, and reintroduces the idea of renewal, bringing it back to the community where it came from, and in its original, oral form.

Aragón’s project includes a video and a series of maps. The hand-drawn maps are alternative power maps that lay bare the power structures in Mexico and the effects of the implementation of the Mesoamerica Project in this power structure.

Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect

9 February - 22 May 2016

Curator: Heidi Ballet

Mexican artist Edgardo Aragón addresses Mexican and global economic and political systems, and zooms in on their effects on Mexican communities.

In his new work, Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect, he provides a critical cartography that shows the power lines that define Mexico, the international Mesoamerica development project and its effects on the community of Cachimbo, located on a peninsula on the border between the states of Oaxaca and Chiapas.

In his work, Aragón often focuses on organised crime and conflict, sometimes re-enacting parts of his own family history that involved violence. His videos look deceptively calm, showing peaceful sunny landscapes, but as they unfold, details accumulate to tell very troubled stories about corrupt power relations. Aragón’s landscape portraits bring to mind “fukeiron”, the “landscape theory” developed by Japanese film-makers in the late 1960s, who put forward the idea that the landscapes one encounters in everyday life, even beautiful, postcard-like ones, are an expression of the dominant political powers. In the case of Aragón, the powers he represents in his work are drug cartels, political parties and foreign companies. He shows how their operations are intricately interlinked through corrupt deals.

Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect examines in close-up the effects of foreign power in Mexico today, which is reminiscent of the foreign control exerted many centuries ago. Mesoamerica was home to a rich civilization that emerged around 10,000 years BC and out of which grew the rich Maya, Aztec and Zapotec cultures, among many others. These cultures were destroyed by the Spanish, who arrived in the 15th and 16th centuries and used Christianity as a tool to discriminate against and subdue the locals. Today, “Mesoamerica” is also the short name for a multi-million dollar development project that is officially called the Mesoamerican Integration and Development Project and is financed and run by the United States. According to its official statement, the project is intended to help the region develop through investment in infrastructure, electricity, telecommunications and transport systems. However, due to rampant corruption at all levels, the project doesn’t benefit the poor communities and instead helps foreign companies that have holdings in the region.

In his video, Aragón zooms in on one particular place on the map of Mexico, namely the community of Cachimbo, which is located on a peninsula in the south, right on the border between the states of Oaxaca and Chiapas. Cachimbo is heavily hit by hurricanes and has to rebuild its infrastructure every year at the end of the hurricane season. It is also witnessing several types of illegal trade due to its border location. Although Cachimbo is very near one of the electricity plants that is part of the Mesoamerica Project, it has no electricity supply apart from a fragile solar energy system that was donated by an Indian NGO. The electricity generated by the wind turbines at the Mesoamerica Project energy plant is sent directly north, to the centre of Oaxaca, from where it is transferred to benefit the foreign-owned companies. In Aragón’s video, we see a protagonist carrying a battery from the centre of Oaxaca to Cachimbo. Aragón tries to correct the wrongs in the system of the Mesoamerica Project, and in a poetic gesture brings the electricity to the community where it should have gone to in the first place. The protagonist passes through the landscape, going past the wind turbines that were built as part of the Mesoamerica Project, and crossing the lake that leads to the peninsula. On arriving in Cachimbo, at the end of the video, the protagonist reads an excerpt from the book The Men Dispersed by the Dance by Andrés Henestrosa.

Andrés Henestrosa was a writer and politician who was born in the region where Cachimbo is located, and played an important role in preserving Zapotec culture from disappearance by collecting oral Zapotec legends and publishing them. The Men Dispersed by the Dance from 1929 is his most famous collection of Zapotec legends. The excerpt that the protagonist is reading in the video is a story in which the violent forces of nature are fighting each other and man is standing in the middle. After a catastrophe has taken place, a time of renewal arrives. Aragón chose this legend because it breaks with the Judeo-Christian tradition that Spanish colonialism left behind in the region and which forces people to accept fatal events and injustices – such as the consequences of the Mesoamerica Project – as destiny. He draws an analogy with the way that neoliberalism is globally accepted to be the only viable option today. Aragón re-inserts this legend into the Cachimbo community, and reintroduces the idea of renewal, bringing it back to the community where it came from, and in its original, oral form.

Aragón’s project includes a video and a series of maps. The hand-drawn maps are alternative power maps that lay bare the power structures in Mexico and the effects of the implementation of the Mesoamerica Project in this power structure.