A Model of The World

10 Jan - 14 Feb 2015

A MODEL OF THE WORLD

A Film Program Curated by Simone Menegoi

Zbyněk Baladrán, Katinka Bock, Guillaume Leblon, Ulrich Polster, Clemens Von Wedemeyer

10 January – 14 February 2015

The Doctor never leaves the house. Walking is a major effort for him. He’s big and stout, and his legs are shaky. Even at home, he rarely budges from his armchair. Most of the time he sits at his desk, sipping brandy and gazing out the window at whatever happens in the village. He watches and takes notes. He writes and sketches. His drawings are simple yet precise, perspective renderings of what the Doctor sees from his window. They put order into the chaos of what lies outside: the mud, the animals roaming through the streets, the hanky-panky, the scheming, the money changing hands.

The Doctor is a character from Béla Tarr’s film Sátántángo . I thought of him as I watched the videos that Zbyněk Baladrán has shot using a fixed camera pointed at a tabletop. On it, two hands draw diagrams, write words, cut geometric shapes from sheets of paper, stack books. Sometimes the images are accompanied by a voiceover, like the Narrator in Sátántángo. The voice comments on what the hands are up to, or else ponders universal questions: the number of instants making up a life, the structure of society, the structure of reality. These are obsessive, solipsistic monologues. Reasonings that follow a logical thread, ignoring how this thread leads them, step by step, into a sphere of abstraction that no longer bears any resemblance to the world we know.

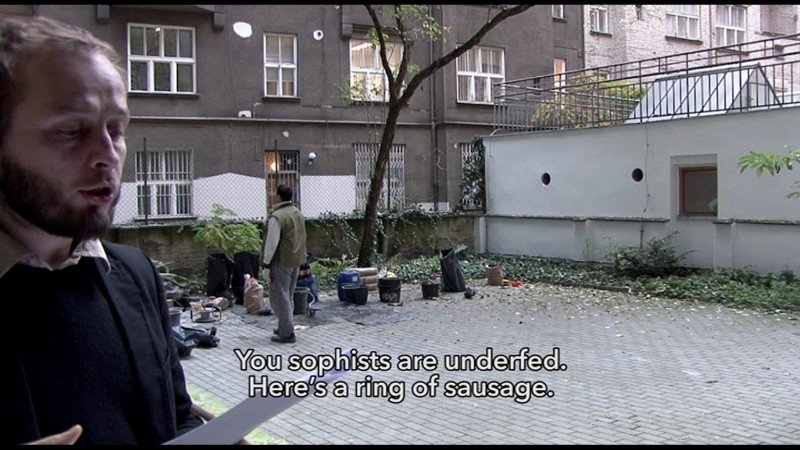

The Czech artist’s videos serve as mileposts throughout the program. Between them, other images flow: videos by Katinka Bock, Guillaume Leblon, Ulrich Polster, Clemens Von Wedemeyer. I suggest imagining, as one watches, that the nameless, faceless character in Baladrán’s videos has lifted his eyes from the table and is looking out the window, like the Doctor in the film by Béla Tarr. What he sees, what we also see, often seems incomprehensible. A man walks around a room whose floor is covered in mud. Objects come flying out the windows of a country house. In a dimly lit room, in the heart of a deserted, snowbound neighborhood, a TV set shows an Italian movie from the Sixties. Effects whose causes we do not know, causes whose effects we will not see. In choosing the videos, I tried to put myself in the position of someone seeing them for the first time, who knows little or nothing about the artists who made them. In some cases this was not hard at all; I really was seeing the videos for the first time, and I really did know little about the artists. I held onto this ignorance. I did my best to look at these images in and of themselves, like views of the world paraded before us, each bearing its own strangeness, and disappearing as mysteriously as they appear.

Since the liquor has run out and his maid seems to have vanished, the Doctor is eventually forced to leave the house. His long wanderings through the muddy streets of the village culminate in a terrible collapse. He is taken to a hospital in the nearest town. When he comes home, some time later, he settles down in front of the usual window, opening his notebook. He patiently waits for someone to come by. Time passes, no one in sight. They must be gathered somewhere in the village, plotting, fornicating, stealing each other blind, the Doctor thinks. They’ll turn up. What the Doctor doesn’t know is that the inhabitants of the village have all gone away, lured by a swindler’s false promises of work. No one is left, not a soul. But he waits, pen in hand, notebook open. He waits for someone, or something, to appear in the space framed by the window. And we wait with him.

1 Béla Tarr, Sátántángo, Hungary / Germany / Switzerland 1994, 419’.

A Film Program Curated by Simone Menegoi

Zbyněk Baladrán, Katinka Bock, Guillaume Leblon, Ulrich Polster, Clemens Von Wedemeyer

10 January – 14 February 2015

The Doctor never leaves the house. Walking is a major effort for him. He’s big and stout, and his legs are shaky. Even at home, he rarely budges from his armchair. Most of the time he sits at his desk, sipping brandy and gazing out the window at whatever happens in the village. He watches and takes notes. He writes and sketches. His drawings are simple yet precise, perspective renderings of what the Doctor sees from his window. They put order into the chaos of what lies outside: the mud, the animals roaming through the streets, the hanky-panky, the scheming, the money changing hands.

The Doctor is a character from Béla Tarr’s film Sátántángo . I thought of him as I watched the videos that Zbyněk Baladrán has shot using a fixed camera pointed at a tabletop. On it, two hands draw diagrams, write words, cut geometric shapes from sheets of paper, stack books. Sometimes the images are accompanied by a voiceover, like the Narrator in Sátántángo. The voice comments on what the hands are up to, or else ponders universal questions: the number of instants making up a life, the structure of society, the structure of reality. These are obsessive, solipsistic monologues. Reasonings that follow a logical thread, ignoring how this thread leads them, step by step, into a sphere of abstraction that no longer bears any resemblance to the world we know.

The Czech artist’s videos serve as mileposts throughout the program. Between them, other images flow: videos by Katinka Bock, Guillaume Leblon, Ulrich Polster, Clemens Von Wedemeyer. I suggest imagining, as one watches, that the nameless, faceless character in Baladrán’s videos has lifted his eyes from the table and is looking out the window, like the Doctor in the film by Béla Tarr. What he sees, what we also see, often seems incomprehensible. A man walks around a room whose floor is covered in mud. Objects come flying out the windows of a country house. In a dimly lit room, in the heart of a deserted, snowbound neighborhood, a TV set shows an Italian movie from the Sixties. Effects whose causes we do not know, causes whose effects we will not see. In choosing the videos, I tried to put myself in the position of someone seeing them for the first time, who knows little or nothing about the artists who made them. In some cases this was not hard at all; I really was seeing the videos for the first time, and I really did know little about the artists. I held onto this ignorance. I did my best to look at these images in and of themselves, like views of the world paraded before us, each bearing its own strangeness, and disappearing as mysteriously as they appear.

Since the liquor has run out and his maid seems to have vanished, the Doctor is eventually forced to leave the house. His long wanderings through the muddy streets of the village culminate in a terrible collapse. He is taken to a hospital in the nearest town. When he comes home, some time later, he settles down in front of the usual window, opening his notebook. He patiently waits for someone to come by. Time passes, no one in sight. They must be gathered somewhere in the village, plotting, fornicating, stealing each other blind, the Doctor thinks. They’ll turn up. What the Doctor doesn’t know is that the inhabitants of the village have all gone away, lured by a swindler’s false promises of work. No one is left, not a soul. But he waits, pen in hand, notebook open. He waits for someone, or something, to appear in the space framed by the window. And we wait with him.

1 Béla Tarr, Sátántángo, Hungary / Germany / Switzerland 1994, 419’.