Helen Marten

30 Apr - 04 Jun 2011

© Helen Marten

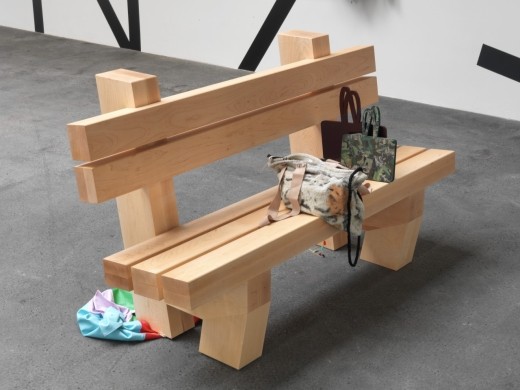

As modest as a maid (womenswear bench, or artisanal garments for a discerning lady) - 2011

Solid Maple bench, stitched stained towel, camouflage tape, bondage rope, laser-cut and powder-coated steel, fake nails, gold chain, Comme des Garcons knot bag

90 x 160 x 55 cm

Photo: Roman März

As modest as a maid (womenswear bench, or artisanal garments for a discerning lady) - 2011

Solid Maple bench, stitched stained towel, camouflage tape, bondage rope, laser-cut and powder-coated steel, fake nails, gold chain, Comme des Garcons knot bag

90 x 160 x 55 cm

Photo: Roman März

HELEN MARTEN

Take a stick and make it sharp

30 April – 4 June, 2011

There’s a medieval thriftiness to the idea that two sharpened sticks dragged over one another could make fire. That something as quiet and dumb as a small section of tree - via impulsive chop and sweat and luck – carries a potential blaze. But there is also a fiddling stupidity in the instruction, no manual or download to offer suggestion of how this blind alchemy could ever be as simple as a match. And there is also the question of what’s missing, of the glaze of actions before and after the taking and the sharpening. So in the title, the exhibition suggests a command, an optimism, but also the image of hapless engineer moving via ancient cartoon process.

Question: Have you ever wondered if the bricks on a façade will absorb dirt quickly enough?

Question: Could the crumbs of sandwiches and masonry dust comingle?

In much of the work there lingers the imprint of sidetracked technology. Images of functionality – social codes of building, sitting, explaining – become petulant competitors for a kind of perfected, static uselessness. Materials build in layers on top of one another, high aspirations towards a total sheen that are repeatedly undercut by fiddling additions and surface foils. Interest is via glitter and detail; elemental icons of shape and substance and branding are packaged and ready to carry away.

Question: If the grave-faced clock and circular fountain are essential logos of a plaza, why is the anonymous statue always the most symbolic exhibitor?

Question: You say violent typography is sexy?

The traditions of symbols in civic and religious buildings are flattened in two wall pieces. A wriggly bastardisation of Tudor formwork – textbook caricature – plays itself off against a cartoons-and-cutouts mural of industrial “progress”, of hands and fists and tools and dirt. In a kind of camp muscle-flexing these classic facades merge in a frothy bind somewhere between the medieval and the mercantile. The cultural building conventionally too proud to be interesting is sexed up and commodified, with dense but chicly blurred-out silhouettes ready for further export and expansion.

Question: What can you open with an uncut key?

Panic Hardware unfolds with all the glib dumbness of a catalogue, a part-bypart mapping of recognizable image and potential use. Handles, hooks, brackets – logos of home and life improvements – are conflated in a celebratory amalgam that is both porno- and typographic. The lowest end of the DIY spectrum is eroticized; the ubiquitous is hilariously paraded in a disintegrating grid where the ordinary and exotic fold into the same strangely digital glaze. Determinately clean, the surface sheen of the woodis even, but its composition is ragged, pixilated, pinned together. There is a stubborn, possessive pride in the flatness, but an impulse for wrongness, too. In this patchwork display centre of brushed curves and softly swollen outlines, the overriding impulse is one of sanitized excess, an abandon to indiscretion that is governed not by taste, but by silent lust or desperation. And via this condensed sprawl, these hefty but neatly aligned shapes unfold a pervasive speed and exuberance that places the touch of a distinctly human hand throughout: we meet the flabby modernist, the urbanist, the industrialist, the fantasist and the crumbs of ideas scaffolded-up in between.

Question: Does the aspiring maiden wax her legs?

Question: How to move between levels?

Question: If the puff of smoke is graphic, is it solid?

Images of benches, ladders, ramps, smoke and paperwork suggest a social presence that is gropingly recognisable. The types of emotion that operate in the time of the lunchtime break, in the chain of idea-space between changing printer cartridges, are given a tactile presence. As motifs of social activity, furniture acts as prop, as psychological charge. With a movement that is one of spreading out, two benches make frictions in conversational space, unfolding clichés of flirtatious exchange and stereotype. Molotov cocktails blur with sleazy bar logos, whilst seasonally fashionable handbags incite conversation with sexualized punctuations of teeth and nails. There’s an attitude of displaying wares, the stickiness of hosting and boasting, of pun and flair.

The evolution of an idea – that primordial growing from dim speck to full sphere – translates via steel tube size as athletically inflected ramp. Smoke is marked out as the true aberration of slapstick, the ultimate obscurer, the mystifier. And iconographic virality forms its own shreds of architectural vernacular. In all this matter, this dazzle and fog lie traces of the beginning ambitions, that ghoulishly cartoonish instruction to take a stick and make it sharp.

Helen Marten (b. 1985) lives and works in London and Macclesfield, UK. She studied at the Ruskin School of Fine Art, University of Oxford. Recent exhibitions include wicked patterns, T293, Naples, I like my heroes marble chested, presented by Carl Kostyal, London, Boule to Braid, Lisson Gallery, London and Untitled, Four Boxes, Denmark.

Upcoming projects include a group exhibition at Catherine Bastide, Brussels, a solo exhibition at CoCo Kunstverein, Vienna, and a project with The Serpentine Gallery, London.

Take a stick and make it sharp

30 April – 4 June, 2011

There’s a medieval thriftiness to the idea that two sharpened sticks dragged over one another could make fire. That something as quiet and dumb as a small section of tree - via impulsive chop and sweat and luck – carries a potential blaze. But there is also a fiddling stupidity in the instruction, no manual or download to offer suggestion of how this blind alchemy could ever be as simple as a match. And there is also the question of what’s missing, of the glaze of actions before and after the taking and the sharpening. So in the title, the exhibition suggests a command, an optimism, but also the image of hapless engineer moving via ancient cartoon process.

Question: Have you ever wondered if the bricks on a façade will absorb dirt quickly enough?

Question: Could the crumbs of sandwiches and masonry dust comingle?

In much of the work there lingers the imprint of sidetracked technology. Images of functionality – social codes of building, sitting, explaining – become petulant competitors for a kind of perfected, static uselessness. Materials build in layers on top of one another, high aspirations towards a total sheen that are repeatedly undercut by fiddling additions and surface foils. Interest is via glitter and detail; elemental icons of shape and substance and branding are packaged and ready to carry away.

Question: If the grave-faced clock and circular fountain are essential logos of a plaza, why is the anonymous statue always the most symbolic exhibitor?

Question: You say violent typography is sexy?

The traditions of symbols in civic and religious buildings are flattened in two wall pieces. A wriggly bastardisation of Tudor formwork – textbook caricature – plays itself off against a cartoons-and-cutouts mural of industrial “progress”, of hands and fists and tools and dirt. In a kind of camp muscle-flexing these classic facades merge in a frothy bind somewhere between the medieval and the mercantile. The cultural building conventionally too proud to be interesting is sexed up and commodified, with dense but chicly blurred-out silhouettes ready for further export and expansion.

Question: What can you open with an uncut key?

Panic Hardware unfolds with all the glib dumbness of a catalogue, a part-bypart mapping of recognizable image and potential use. Handles, hooks, brackets – logos of home and life improvements – are conflated in a celebratory amalgam that is both porno- and typographic. The lowest end of the DIY spectrum is eroticized; the ubiquitous is hilariously paraded in a disintegrating grid where the ordinary and exotic fold into the same strangely digital glaze. Determinately clean, the surface sheen of the woodis even, but its composition is ragged, pixilated, pinned together. There is a stubborn, possessive pride in the flatness, but an impulse for wrongness, too. In this patchwork display centre of brushed curves and softly swollen outlines, the overriding impulse is one of sanitized excess, an abandon to indiscretion that is governed not by taste, but by silent lust or desperation. And via this condensed sprawl, these hefty but neatly aligned shapes unfold a pervasive speed and exuberance that places the touch of a distinctly human hand throughout: we meet the flabby modernist, the urbanist, the industrialist, the fantasist and the crumbs of ideas scaffolded-up in between.

Question: Does the aspiring maiden wax her legs?

Question: How to move between levels?

Question: If the puff of smoke is graphic, is it solid?

Images of benches, ladders, ramps, smoke and paperwork suggest a social presence that is gropingly recognisable. The types of emotion that operate in the time of the lunchtime break, in the chain of idea-space between changing printer cartridges, are given a tactile presence. As motifs of social activity, furniture acts as prop, as psychological charge. With a movement that is one of spreading out, two benches make frictions in conversational space, unfolding clichés of flirtatious exchange and stereotype. Molotov cocktails blur with sleazy bar logos, whilst seasonally fashionable handbags incite conversation with sexualized punctuations of teeth and nails. There’s an attitude of displaying wares, the stickiness of hosting and boasting, of pun and flair.

The evolution of an idea – that primordial growing from dim speck to full sphere – translates via steel tube size as athletically inflected ramp. Smoke is marked out as the true aberration of slapstick, the ultimate obscurer, the mystifier. And iconographic virality forms its own shreds of architectural vernacular. In all this matter, this dazzle and fog lie traces of the beginning ambitions, that ghoulishly cartoonish instruction to take a stick and make it sharp.

Helen Marten (b. 1985) lives and works in London and Macclesfield, UK. She studied at the Ruskin School of Fine Art, University of Oxford. Recent exhibitions include wicked patterns, T293, Naples, I like my heroes marble chested, presented by Carl Kostyal, London, Boule to Braid, Lisson Gallery, London and Untitled, Four Boxes, Denmark.

Upcoming projects include a group exhibition at Catherine Bastide, Brussels, a solo exhibition at CoCo Kunstverein, Vienna, and a project with The Serpentine Gallery, London.