Helmut Stallaerts

22 Jan - 05 Mar 2011

HELMUT STALLAERTS

A Great Void

22 January – 5 March 2011

In December 1916, Kazimir Malevich showed his Black Square for the first time: a black square painted on a larger white canvas. He installed the work close to the ceiling and in the corner of an exhibition room. This placement had a special symbolic significance, because in the Russian orthodox tradition, this is the place where icons are hung. It seems as if Malevich was trying to bring the everything and the nothing together: unlimited eternity and absolute emptiness. The first version of this black square developed a surprising life of its own: the many layers of paint revealed over time more and more craquelure, the paint drying out unexpectedly broke up the monochrome plane. Thus the changes in Malevich’s works confirmed unexpectedly the old scientific theory of the horror vacui[1], according to which both humans and nature abhor the void. The mental void which Malevich wanted to create on his canvas was undermined and cancelled out by the physical presence of the small cracks.

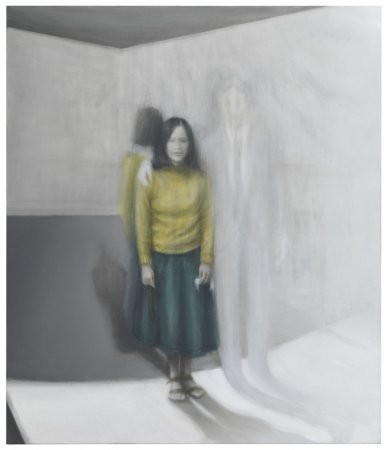

The discomfort which is generated by a void or a nothing is one of the recurring impulses in Helmut Stallaerts’ oeuvre. The pictures he creates are always poised between being and non-being. He does not picture the void itself (even Malevich shows us that that is impossible), but rather that which envelops the void. Many of Stallaerts’ works are best understood as dreams or hallucinations which on the one hand lead us closer to the enigma, but on the other hand appear as an unknown black hole, throwing us off balance.

One of the central works in the exhibition “A Great Void” is The Count (2010). Four people sit on a podium and stare at an empty table. The room is closed off by a grand yellowish-golden curtain. Through the curtain, blurred perspective lines forming an empty, seemingly endless corridor are visible. The shadows of the sitting figures slip away, underneath the curtain, in the direction of the empty space. The thin atmosphere in which the events are steeped, feels like an evacuated room where the aspect of “time” is cancelled, as if in this world, the sense of discomfort would last forever.

Man is undoubtedly the central motif in Helmut Stallaerts’ complex and broad oeuvre. It is not man in the here and now, but alienated man, blurred and absent. In a rather theatrical and often awkward way, he shows himself, poses for his audience. The actions he undertakes frequently smack of an undefined ritual. There is nothing comical about the absurd atmosphere created in this way; on the contrary, it is very strange and dark. The environment by which his human existence is framed is similarly alien: without any anecdotal detail, sterile and cold.

The obsessive aesthetics that Stallaerts develops in his oeuvre creates a sacred dimension through which the works always relate to one another. This context creates a core around which all his works circulate. This enigmatic core, however, remains: one can merely get closer to it, but never actually reach it. An exhibition by Helmut Stallaerts has the power to generate a view on the mysteries of being; it also confronts us with a truth that remains dark and that unhinges our own fictive truths.

Tanguy Eeckhout

[1] In the natural sciences of antiquity and the Middle Ages, horror vacui (fear of empty spaces) stood for the theory that nature abhors a vacuum: a piece of empty soil is quickly covered with vegetation, a barrel where the liquid escapes fills with oxygen... (source: www.wikipedia.org) In art, horror vacui stands for a formal dissolution of the pictorial space: the artist decides to fill every empty space so that the composition is regarded as full.

A Great Void

22 January – 5 March 2011

In December 1916, Kazimir Malevich showed his Black Square for the first time: a black square painted on a larger white canvas. He installed the work close to the ceiling and in the corner of an exhibition room. This placement had a special symbolic significance, because in the Russian orthodox tradition, this is the place where icons are hung. It seems as if Malevich was trying to bring the everything and the nothing together: unlimited eternity and absolute emptiness. The first version of this black square developed a surprising life of its own: the many layers of paint revealed over time more and more craquelure, the paint drying out unexpectedly broke up the monochrome plane. Thus the changes in Malevich’s works confirmed unexpectedly the old scientific theory of the horror vacui[1], according to which both humans and nature abhor the void. The mental void which Malevich wanted to create on his canvas was undermined and cancelled out by the physical presence of the small cracks.

The discomfort which is generated by a void or a nothing is one of the recurring impulses in Helmut Stallaerts’ oeuvre. The pictures he creates are always poised between being and non-being. He does not picture the void itself (even Malevich shows us that that is impossible), but rather that which envelops the void. Many of Stallaerts’ works are best understood as dreams or hallucinations which on the one hand lead us closer to the enigma, but on the other hand appear as an unknown black hole, throwing us off balance.

One of the central works in the exhibition “A Great Void” is The Count (2010). Four people sit on a podium and stare at an empty table. The room is closed off by a grand yellowish-golden curtain. Through the curtain, blurred perspective lines forming an empty, seemingly endless corridor are visible. The shadows of the sitting figures slip away, underneath the curtain, in the direction of the empty space. The thin atmosphere in which the events are steeped, feels like an evacuated room where the aspect of “time” is cancelled, as if in this world, the sense of discomfort would last forever.

Man is undoubtedly the central motif in Helmut Stallaerts’ complex and broad oeuvre. It is not man in the here and now, but alienated man, blurred and absent. In a rather theatrical and often awkward way, he shows himself, poses for his audience. The actions he undertakes frequently smack of an undefined ritual. There is nothing comical about the absurd atmosphere created in this way; on the contrary, it is very strange and dark. The environment by which his human existence is framed is similarly alien: without any anecdotal detail, sterile and cold.

The obsessive aesthetics that Stallaerts develops in his oeuvre creates a sacred dimension through which the works always relate to one another. This context creates a core around which all his works circulate. This enigmatic core, however, remains: one can merely get closer to it, but never actually reach it. An exhibition by Helmut Stallaerts has the power to generate a view on the mysteries of being; it also confronts us with a truth that remains dark and that unhinges our own fictive truths.

Tanguy Eeckhout

[1] In the natural sciences of antiquity and the Middle Ages, horror vacui (fear of empty spaces) stood for the theory that nature abhors a vacuum: a piece of empty soil is quickly covered with vegetation, a barrel where the liquid escapes fills with oxygen... (source: www.wikipedia.org) In art, horror vacui stands for a formal dissolution of the pictorial space: the artist decides to fill every empty space so that the composition is regarded as full.