Frank Hannon

13 Jan - 17 Feb 2007

FRANK HANNON

"Upside down rabbit country"

13 January – 17 February 2007

Opening Saturday 13 January, 5-8 pm

Memory is a strange editor. A fragment; a corner. A number 8 on a worn-out wall. A rabbit the wrong way up; an arm reaching out; an inexplicable shift in colour. Images drift by: the curve of a flower, a torn paper teardrop, and the face of someone from another time. A field recalled in a blade of grass, a building in a single brick. A patch of plaster dissolving in a watery sky. Weathered surfaces; a picture where a picture shouldn’t be. Black paddles resist thoroughfares; black holes suck and release energy; wit plays with melancholy. Surfaces as frail as hair hover beneath ones as tough as bone. An image too close to see; an image so faint it disappears. These images exist like the residue of childhood – a solid feeling that can seem counter-intuitive (how can something that took so long, be remembered so elusively?).

Recently I have been reading Psychoanalysis, The Impossible Profession, by Janet Malcolm, and came across the following lines. They immediately made me think about Frank Hannon’s approach to making pictures and sculptures.

In a well-known passage in the The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), Freud likens the feat of the patient who suspends his critical faculties and says everything and anything that comes into his mind, regardless of its triviality, irrelevance, or unpleasantness, to that of a the poet during the act of creation. He quotes from a letter that Schiller wrote in 1788 in reply to a friend who had complained of meager literary production:

‘...It seems a bad thing and detrimental to the creative work of the mind if Reason makes too close an examination of the ideas as they come pouring in – at the very gateway, as it were. Looked at in isolation, a thought may seem very trivial or very fantastic; but it may be made important by another thought that comes after it and in conjunction with other thoughts that may seem equally absurd, it may turn out to form a most effective link. Reason cannot form any opinion upon all this unless it retains the thought long enough to look at it connection with the others. On the other hand, where there is a certain creative mind, Reason – so it seems to me – relaxes its watch upon the gates, and the ideas rush in pell-mell, and only then does it look them through and examine them in a mass ... you critics, or whatever else you may call yourselves, are ashamed or frightened of the momentary and transient extravagances which are to be found in all truly creative minds and whose longer or shorter duration distinguishes the thinking artist from the dreamer.’

Much of Frank Hannon’s work is inspired by memories of growing up on a farm on the west coast of Ireland, but he is less interested in the recollection of resemblance than in evoking a mood or a feeling. Memory is, by its nature, unique, fragmented and resistant to reason. (The past is indifferent to logic.) Everyone who looks at a work of art creates, in a sense, their own work; memories can’t help but infect each new act of looking.

Frank Hannon makes images and objects whose meaning can’t be rushed. Every object rubs up against another, bleeds into another. New shapes evolve from ones so well worn they shine with age. One of the beauties of Frank’s work is that it never complains about the weight of the past; it examines fragments gladly, with curiosity and delicacy. His work makes tangible that remembering is an activity that never ends and looking is one that propels memories into the future.

© Frank Hannon

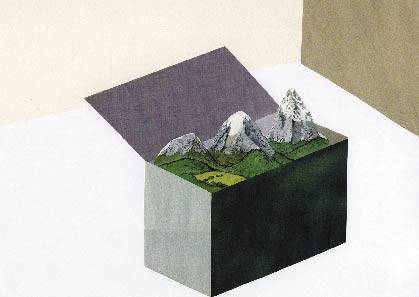

Upside down rabbit country, 2006

Collage, 10.74 x 15 cm

"Upside down rabbit country"

13 January – 17 February 2007

Opening Saturday 13 January, 5-8 pm

Memory is a strange editor. A fragment; a corner. A number 8 on a worn-out wall. A rabbit the wrong way up; an arm reaching out; an inexplicable shift in colour. Images drift by: the curve of a flower, a torn paper teardrop, and the face of someone from another time. A field recalled in a blade of grass, a building in a single brick. A patch of plaster dissolving in a watery sky. Weathered surfaces; a picture where a picture shouldn’t be. Black paddles resist thoroughfares; black holes suck and release energy; wit plays with melancholy. Surfaces as frail as hair hover beneath ones as tough as bone. An image too close to see; an image so faint it disappears. These images exist like the residue of childhood – a solid feeling that can seem counter-intuitive (how can something that took so long, be remembered so elusively?).

Recently I have been reading Psychoanalysis, The Impossible Profession, by Janet Malcolm, and came across the following lines. They immediately made me think about Frank Hannon’s approach to making pictures and sculptures.

In a well-known passage in the The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), Freud likens the feat of the patient who suspends his critical faculties and says everything and anything that comes into his mind, regardless of its triviality, irrelevance, or unpleasantness, to that of a the poet during the act of creation. He quotes from a letter that Schiller wrote in 1788 in reply to a friend who had complained of meager literary production:

‘...It seems a bad thing and detrimental to the creative work of the mind if Reason makes too close an examination of the ideas as they come pouring in – at the very gateway, as it were. Looked at in isolation, a thought may seem very trivial or very fantastic; but it may be made important by another thought that comes after it and in conjunction with other thoughts that may seem equally absurd, it may turn out to form a most effective link. Reason cannot form any opinion upon all this unless it retains the thought long enough to look at it connection with the others. On the other hand, where there is a certain creative mind, Reason – so it seems to me – relaxes its watch upon the gates, and the ideas rush in pell-mell, and only then does it look them through and examine them in a mass ... you critics, or whatever else you may call yourselves, are ashamed or frightened of the momentary and transient extravagances which are to be found in all truly creative minds and whose longer or shorter duration distinguishes the thinking artist from the dreamer.’

Much of Frank Hannon’s work is inspired by memories of growing up on a farm on the west coast of Ireland, but he is less interested in the recollection of resemblance than in evoking a mood or a feeling. Memory is, by its nature, unique, fragmented and resistant to reason. (The past is indifferent to logic.) Everyone who looks at a work of art creates, in a sense, their own work; memories can’t help but infect each new act of looking.

Frank Hannon makes images and objects whose meaning can’t be rushed. Every object rubs up against another, bleeds into another. New shapes evolve from ones so well worn they shine with age. One of the beauties of Frank’s work is that it never complains about the weight of the past; it examines fragments gladly, with curiosity and delicacy. His work makes tangible that remembering is an activity that never ends and looking is one that propels memories into the future.

© Frank Hannon

Upside down rabbit country, 2006

Collage, 10.74 x 15 cm