Capturing Time

13 Sep - 08 Nov 2009

CAPTURING TIME

13 September – 8 November 2009

Curated by: Jeremy Lewison

Artists : Katinka Bock, Tacita Dean, Elizabeth McAlpine, Simon Starling, Christiane Baumgartner, Jeremy Lewison, Zarina Bhimji

Kadist Art Foundation is pleased to announce the first exhibition to be drawn from its collection. Capturing Time, selected by Jeremy Lewison, a member of the Kadist Committee, looks at the way in which six artists address issues relating to time.

With: Christiane Baumgartner, Zarina Bhimji, Katinka Bock, Tacita Dean, Elizabeth McAlpine and Simon Starling.

A recurring theme in art history, time has always preoccupied artists: the tradition of the vanitas still life, the self portraits of an ageing Rembrandt, the depiction of shifting daylight in the paintings of the Impressionists have all been vehicles for the contemplation of the passage of time. In the twentieth century film, a time-based medium, has been a natural repository for the investigation of time. Time and motion are inseparable twins, for time is unremitting. Some might wish for the suspension of time, others to travel back in time whether physically or through memory. The impermanence of life, its relentless pace and tendency to self-destruction continues to preoccupy artists.

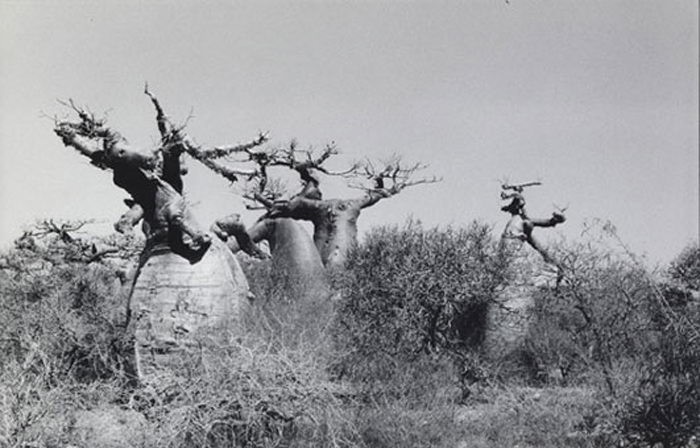

In Tacita Dean’s meditative Baobab, the primeval landscape of Madagascar has the appearance of being out of time, an eternal witness to the transience of human and animal life. In a digital age Dean’s use of black and white film is both anachronistic and archaic, a medium from what seems to be a bygone era.

A similar sense of melancholy emanates from the work by filmmaker Zarina Bhimji, whose films have been based on her experience as a refugee from the Uganda of Idi Amin. In «Bapa Closed his Heart. It Was Over», a photograph of a room at Entebbe airport that has fallen into a state of disrepair, she addresses issues connected with the memory and loss of the émigré.

The use of low technology lies at the heart of Simon Starling’s project, Autoxylopyrocycloboros. Starling used a boat salvaged from the bottom of Lake Windermere and fitted it with a stove to generate steam power. The work documents in episodic slide form a continuous action of self-destruction. Elements of the wooden boat are burned to generate power until it reaches a tipping point and finally sinks, returning the ship to the bottom of the lake.

Christiane Baumgartner’s Formation I and II are woodcuts derived from World War Two film footage. From a video she shot of the television screen, via a computer generated moiré pattern, Baumgartner has stilled the image and suspended time. Like Dean and Starling, Baumgartner employs the technology of yesteryear, but to make an image that translates the technological to the hand-made, the moving to the still and the quick to the stationary.

Filmed in black and white on Super 8, yet another dinosaur film medium normally associated with home movies in the 1960s, Katinka Bock’s subject becomes Sisyphean by virtue of its absurd repetition and the impossibility of the task she set: a boat filled with stones inevitably capsizes and sinks.Elizabeth McAlpine’s «98m (The Height of the Campanile, San Marco, Venice...)» is filmed like the Bock, in Super 8.

McAlpine’s work is projected onto the wall, postcard size, as though it were a souvenir home movie. Knowing the Campanile is ninety-eight metres high, McAlpine used ninety-eight metres of film to depict it from bottom to top so that the film becomes a physical equivalent of the tower as well as a visual evocation. Thus the time it takes to view the film is a temporal translation of the distance from bottom to top of the tower.

Ultimately, time is also a concept underlying the very notion of a collection since the collection reveals the history of inidual and collective taste in particular moments. Kadist Art Foundation came into being as a collection before opening a space. Over a period of years the activity of collecting has contributed to constructing its artistic identity. Exhibiting a collection is always more or less related to assessing some kind of present state: taking a step back, looking back before constructing the future. Kadist’s program and collection are intimately related – as much through the residency program and exhibitions as its collecting strategy – and it privileges specific viewpoints. Thus the first display of the collection is not an overview but an examination of a particular aspect. Inviting a member of the committee to curate an exhibition drawn from the collection is also a way to reveal something of the Foundation’s identity.

13 September – 8 November 2009

Curated by: Jeremy Lewison

Artists : Katinka Bock, Tacita Dean, Elizabeth McAlpine, Simon Starling, Christiane Baumgartner, Jeremy Lewison, Zarina Bhimji

Kadist Art Foundation is pleased to announce the first exhibition to be drawn from its collection. Capturing Time, selected by Jeremy Lewison, a member of the Kadist Committee, looks at the way in which six artists address issues relating to time.

With: Christiane Baumgartner, Zarina Bhimji, Katinka Bock, Tacita Dean, Elizabeth McAlpine and Simon Starling.

A recurring theme in art history, time has always preoccupied artists: the tradition of the vanitas still life, the self portraits of an ageing Rembrandt, the depiction of shifting daylight in the paintings of the Impressionists have all been vehicles for the contemplation of the passage of time. In the twentieth century film, a time-based medium, has been a natural repository for the investigation of time. Time and motion are inseparable twins, for time is unremitting. Some might wish for the suspension of time, others to travel back in time whether physically or through memory. The impermanence of life, its relentless pace and tendency to self-destruction continues to preoccupy artists.

In Tacita Dean’s meditative Baobab, the primeval landscape of Madagascar has the appearance of being out of time, an eternal witness to the transience of human and animal life. In a digital age Dean’s use of black and white film is both anachronistic and archaic, a medium from what seems to be a bygone era.

A similar sense of melancholy emanates from the work by filmmaker Zarina Bhimji, whose films have been based on her experience as a refugee from the Uganda of Idi Amin. In «Bapa Closed his Heart. It Was Over», a photograph of a room at Entebbe airport that has fallen into a state of disrepair, she addresses issues connected with the memory and loss of the émigré.

The use of low technology lies at the heart of Simon Starling’s project, Autoxylopyrocycloboros. Starling used a boat salvaged from the bottom of Lake Windermere and fitted it with a stove to generate steam power. The work documents in episodic slide form a continuous action of self-destruction. Elements of the wooden boat are burned to generate power until it reaches a tipping point and finally sinks, returning the ship to the bottom of the lake.

Christiane Baumgartner’s Formation I and II are woodcuts derived from World War Two film footage. From a video she shot of the television screen, via a computer generated moiré pattern, Baumgartner has stilled the image and suspended time. Like Dean and Starling, Baumgartner employs the technology of yesteryear, but to make an image that translates the technological to the hand-made, the moving to the still and the quick to the stationary.

Filmed in black and white on Super 8, yet another dinosaur film medium normally associated with home movies in the 1960s, Katinka Bock’s subject becomes Sisyphean by virtue of its absurd repetition and the impossibility of the task she set: a boat filled with stones inevitably capsizes and sinks.Elizabeth McAlpine’s «98m (The Height of the Campanile, San Marco, Venice...)» is filmed like the Bock, in Super 8.

McAlpine’s work is projected onto the wall, postcard size, as though it were a souvenir home movie. Knowing the Campanile is ninety-eight metres high, McAlpine used ninety-eight metres of film to depict it from bottom to top so that the film becomes a physical equivalent of the tower as well as a visual evocation. Thus the time it takes to view the film is a temporal translation of the distance from bottom to top of the tower.

Ultimately, time is also a concept underlying the very notion of a collection since the collection reveals the history of inidual and collective taste in particular moments. Kadist Art Foundation came into being as a collection before opening a space. Over a period of years the activity of collecting has contributed to constructing its artistic identity. Exhibiting a collection is always more or less related to assessing some kind of present state: taking a step back, looking back before constructing the future. Kadist’s program and collection are intimately related – as much through the residency program and exhibitions as its collecting strategy – and it privileges specific viewpoints. Thus the first display of the collection is not an overview but an examination of a particular aspect. Inviting a member of the committee to curate an exhibition drawn from the collection is also a way to reveal something of the Foundation’s identity.