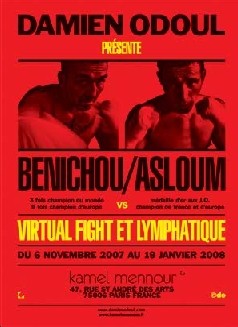

Damien Odoul

06 Nov 2007 - 19 Jan 2008

DAMIEN ODOUL

Born in 1968, Damien Odoul has created a universe whose style is impossible to pin down. Spanning film, performance art, poetry and theatre, his work “constantly flouts the limits history has imposed on the genres”

1 . In the space of fifteen years or so, Damien Odoul has written and directed several art videos, 11 short films and 5 feature-length films, including a trilogy on the theme of ‘the double’: Morasseix, Errance, Le Souffle, which was awarded the Special Jury Prize at the 2001 Venice Film Festival. En attendant le Déluge (2003, “Waiting for the flood”), a hedonistic tale that recounts the pleasures of life from its beginnings until death, was selected for the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, while his latest film, L’Histoire de Richard O. (2006, “The Story of Richard O.”), has been playing in cinemas for six consecutive weeks now. A prolific and multi-talented creative force, this year he will publish his Poèmes du Milieu. According to the artist, it is “visceral poetry”, where words somersault between meaning and sound, murmur and explode through the breath of the artist. That he is many men in one is one of the most striking observations to emerge from the Atelier de Création Radiophonique (“Creative Radio Workshop”), which will be dedicated to Poèmes du Milieu, read by the artist, and broadcast by the national radio station France Culture (16 December at 10.10 pm). Introduced to boxing by his maternal grandfather, who was a champion in the twenties, Damien Odoul is passionate about the sport. He himself takes part in Greco-Roman wrestling.

In both his work and his life, art and combat are inextricably linked, like a mobilisation of energy, a deflagration between two bodily masses, a mix of humours in the form of a resistance to the sanitisation of thought. For his exhibition at Galerie Kamel Mennour’s experimental Tube-Espace, Damien Odoul has imagined an unlikely and inspired match between Fabrice Bénichou and Brahim Asloum.

Forty-three-year-old Bénichou, three times World Champion, five times European Champion, and of legendary courage, is the enfant terrible of the boxing world, his chest and arms covered with tattoos.

Twenty-eight-year-old Asloum, the new idol of French boxing, has already won Olympic gold and become French and European Champion. He is currently preparing for the next World Championship.

With this Janus-faced portrait, Damien Odoul returns to the myth of the double that permeates his entire œuvre. In the first room, two photographic triptychs show the boxers facing the lens, with close-ups of their fists flying and their faces: blow by blow, the snapshots reveal each one’s traits. The blurredness of these time-images is reminiscent of Bacon: where the gesture speeds up, the colour intensifies to the point of cancelling itself out. As if forming a chronophotographic sequence, the movement seems to pass from one image to the other.

For the two videos, time seems to have been suspended and turned into movement. The obsession for duality infuses these works as well: not only are they mutually synchronous, they are also constructed symmetrically. Filmed first of all during a punch-bag training session, the two boxers then go on to shadow box (whence the name of the video). With this exercise, the boxer aims to improve his reaction times by anticipating his own movements in front of a mirror. The result is both disturbingly and effectively schizophrenic. Béinchou shows himself to be a warrior and “swashbuckler”, whereas Asloum is much more focussed on “style”. For Damien Odoul, this alternation seems to sum up the transformation of modern boxing. For him, it has moved away from “eroticism and become pornography”; in other words, it has become less disorderly, less explosive, and more like a rational and reasoned piece of engineering. Unusually, we hear the two boxers swear in the videos: they curse their own reflections using the kinds of deadly phrase that Mohamed Ali employed against Georges Foreman in order to wind him up and put him off him during their 1974 match in Kinshasa (“the Rumble in the Jungle”). With the fictional encounter Asloum v. Bénichou, Damien Odoul pays homage to this mythical episode in international boxing, which was won, against all the odds, by Ali. But here, there is no victory; no loser. As the title of the exhibition indicates, it consists rather of a combat that is both virtual (the English part of the title refers to a video game) and phlegmatic, i.e. non-aggressive, without bloodshed. The gap between these two extremes expresses the amplitude of Damien Odoul’s universe, as powerful in its contemporariness as in its antique or primitive values (phlegmatic being one of the four temperaments from the ancient medical concept of the Humours).

At the entrance to the exhibition is a punch-bag placed above a cairn (the pile of stones that serves as a marker on mountain paths), in the form of an hourglass: a sign of the freezing of time in this virtual combat. Or perhaps it is rather to be seen as the artist’s self-portrait, the head and body ready to receive the blows, while the feet remain firmly anchored to the ground. And, perhaps, the sound of the uppercuts and hooks may resemble so many whispered words or swaying onomatopoeias.

Born in 1968, Damien Odoul has created a universe whose style is impossible to pin down. Spanning film, performance art, poetry and theatre, his work “constantly flouts the limits history has imposed on the genres”

1 . In the space of fifteen years or so, Damien Odoul has written and directed several art videos, 11 short films and 5 feature-length films, including a trilogy on the theme of ‘the double’: Morasseix, Errance, Le Souffle, which was awarded the Special Jury Prize at the 2001 Venice Film Festival. En attendant le Déluge (2003, “Waiting for the flood”), a hedonistic tale that recounts the pleasures of life from its beginnings until death, was selected for the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, while his latest film, L’Histoire de Richard O. (2006, “The Story of Richard O.”), has been playing in cinemas for six consecutive weeks now. A prolific and multi-talented creative force, this year he will publish his Poèmes du Milieu. According to the artist, it is “visceral poetry”, where words somersault between meaning and sound, murmur and explode through the breath of the artist. That he is many men in one is one of the most striking observations to emerge from the Atelier de Création Radiophonique (“Creative Radio Workshop”), which will be dedicated to Poèmes du Milieu, read by the artist, and broadcast by the national radio station France Culture (16 December at 10.10 pm). Introduced to boxing by his maternal grandfather, who was a champion in the twenties, Damien Odoul is passionate about the sport. He himself takes part in Greco-Roman wrestling.

In both his work and his life, art and combat are inextricably linked, like a mobilisation of energy, a deflagration between two bodily masses, a mix of humours in the form of a resistance to the sanitisation of thought. For his exhibition at Galerie Kamel Mennour’s experimental Tube-Espace, Damien Odoul has imagined an unlikely and inspired match between Fabrice Bénichou and Brahim Asloum.

Forty-three-year-old Bénichou, three times World Champion, five times European Champion, and of legendary courage, is the enfant terrible of the boxing world, his chest and arms covered with tattoos.

Twenty-eight-year-old Asloum, the new idol of French boxing, has already won Olympic gold and become French and European Champion. He is currently preparing for the next World Championship.

With this Janus-faced portrait, Damien Odoul returns to the myth of the double that permeates his entire œuvre. In the first room, two photographic triptychs show the boxers facing the lens, with close-ups of their fists flying and their faces: blow by blow, the snapshots reveal each one’s traits. The blurredness of these time-images is reminiscent of Bacon: where the gesture speeds up, the colour intensifies to the point of cancelling itself out. As if forming a chronophotographic sequence, the movement seems to pass from one image to the other.

For the two videos, time seems to have been suspended and turned into movement. The obsession for duality infuses these works as well: not only are they mutually synchronous, they are also constructed symmetrically. Filmed first of all during a punch-bag training session, the two boxers then go on to shadow box (whence the name of the video). With this exercise, the boxer aims to improve his reaction times by anticipating his own movements in front of a mirror. The result is both disturbingly and effectively schizophrenic. Béinchou shows himself to be a warrior and “swashbuckler”, whereas Asloum is much more focussed on “style”. For Damien Odoul, this alternation seems to sum up the transformation of modern boxing. For him, it has moved away from “eroticism and become pornography”; in other words, it has become less disorderly, less explosive, and more like a rational and reasoned piece of engineering. Unusually, we hear the two boxers swear in the videos: they curse their own reflections using the kinds of deadly phrase that Mohamed Ali employed against Georges Foreman in order to wind him up and put him off him during their 1974 match in Kinshasa (“the Rumble in the Jungle”). With the fictional encounter Asloum v. Bénichou, Damien Odoul pays homage to this mythical episode in international boxing, which was won, against all the odds, by Ali. But here, there is no victory; no loser. As the title of the exhibition indicates, it consists rather of a combat that is both virtual (the English part of the title refers to a video game) and phlegmatic, i.e. non-aggressive, without bloodshed. The gap between these two extremes expresses the amplitude of Damien Odoul’s universe, as powerful in its contemporariness as in its antique or primitive values (phlegmatic being one of the four temperaments from the ancient medical concept of the Humours).

At the entrance to the exhibition is a punch-bag placed above a cairn (the pile of stones that serves as a marker on mountain paths), in the form of an hourglass: a sign of the freezing of time in this virtual combat. Or perhaps it is rather to be seen as the artist’s self-portrait, the head and body ready to receive the blows, while the feet remain firmly anchored to the ground. And, perhaps, the sound of the uppercuts and hooks may resemble so many whispered words or swaying onomatopoeias.