Thomas Brummett

Of Heaven, Earth and Light

19 Jan - 01 Apr 2017

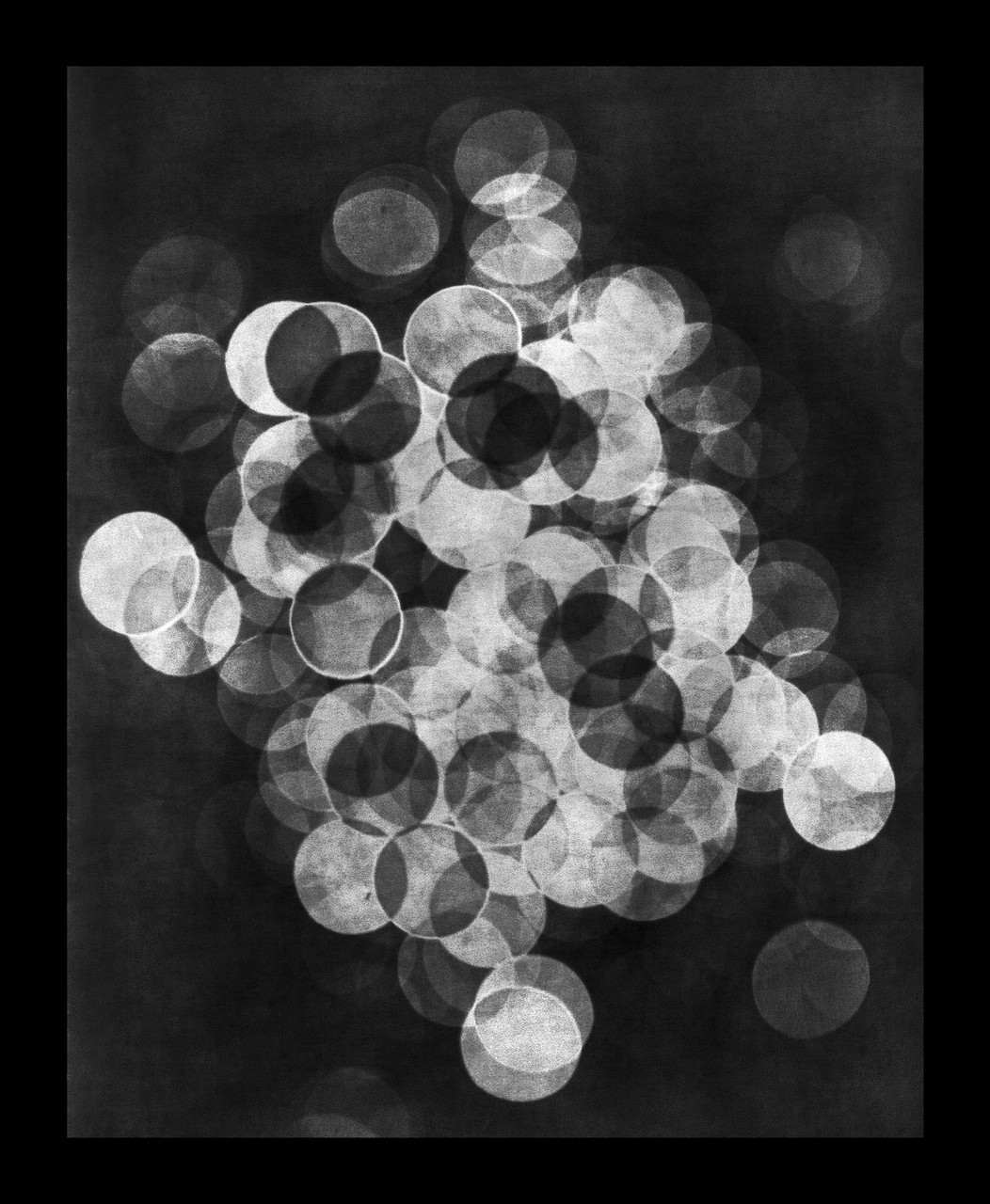

Thomas Brummett: Light Projection #8

2016, Gelatin silver print, Ed. 1/2

120 x 99 cm / 47 1/4 x 39 in

Copyright: Thomas Brummett, Courtesy of Galerie Karsten Greve

2016, Gelatin silver print, Ed. 1/2

120 x 99 cm / 47 1/4 x 39 in

Copyright: Thomas Brummett, Courtesy of Galerie Karsten Greve

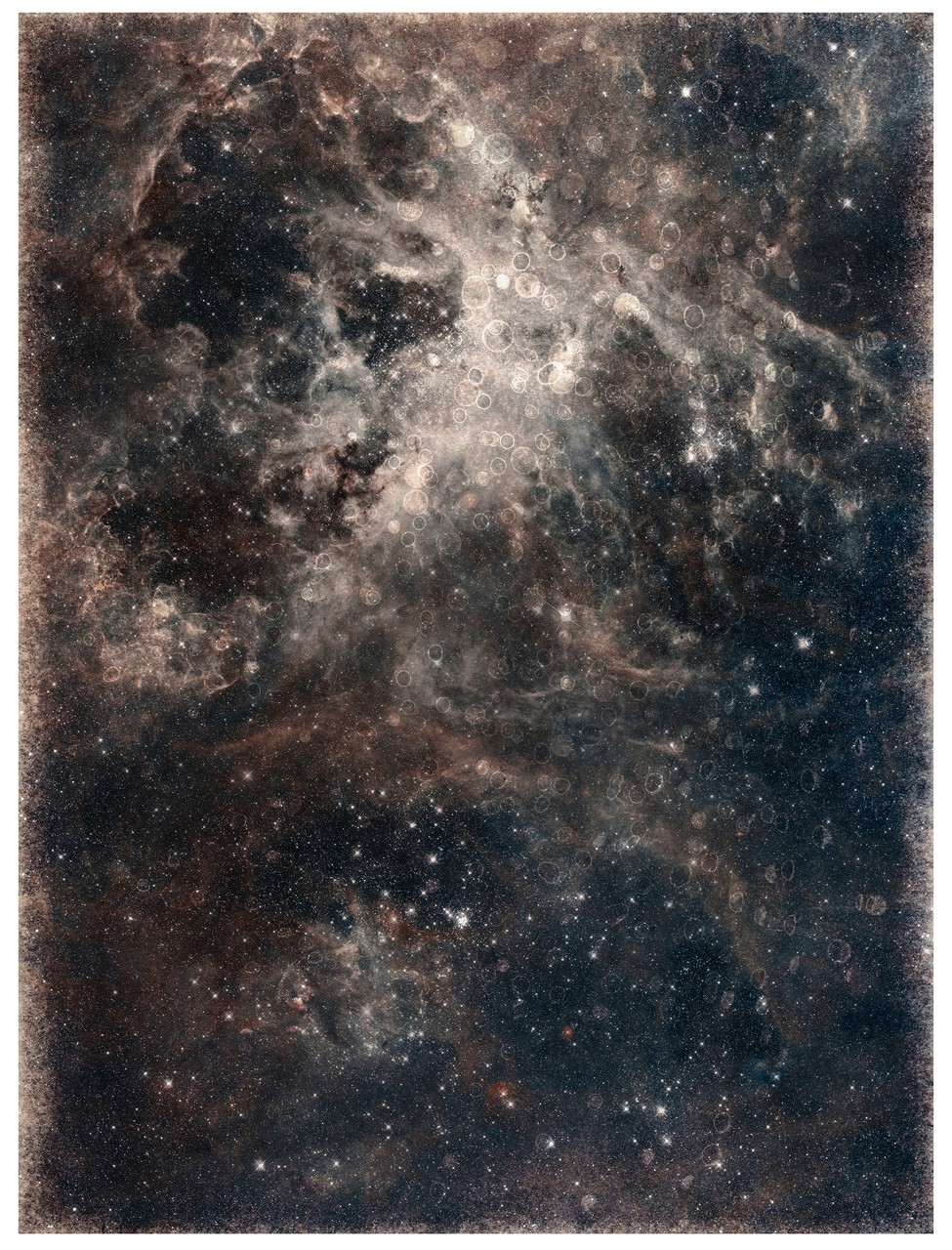

Thomas Brummett: Infinities #8 (For Whistler)

2013, Pure cotton paper printed with 100 year archival pigment ink, Ed. 3/5

127 x 99 cm / 50 x 39 in

Copyright: Thomas Brummett, Courtesy of Galerie Karsten Greve

2013, Pure cotton paper printed with 100 year archival pigment ink, Ed. 3/5

127 x 99 cm / 50 x 39 in

Copyright: Thomas Brummett, Courtesy of Galerie Karsten Greve

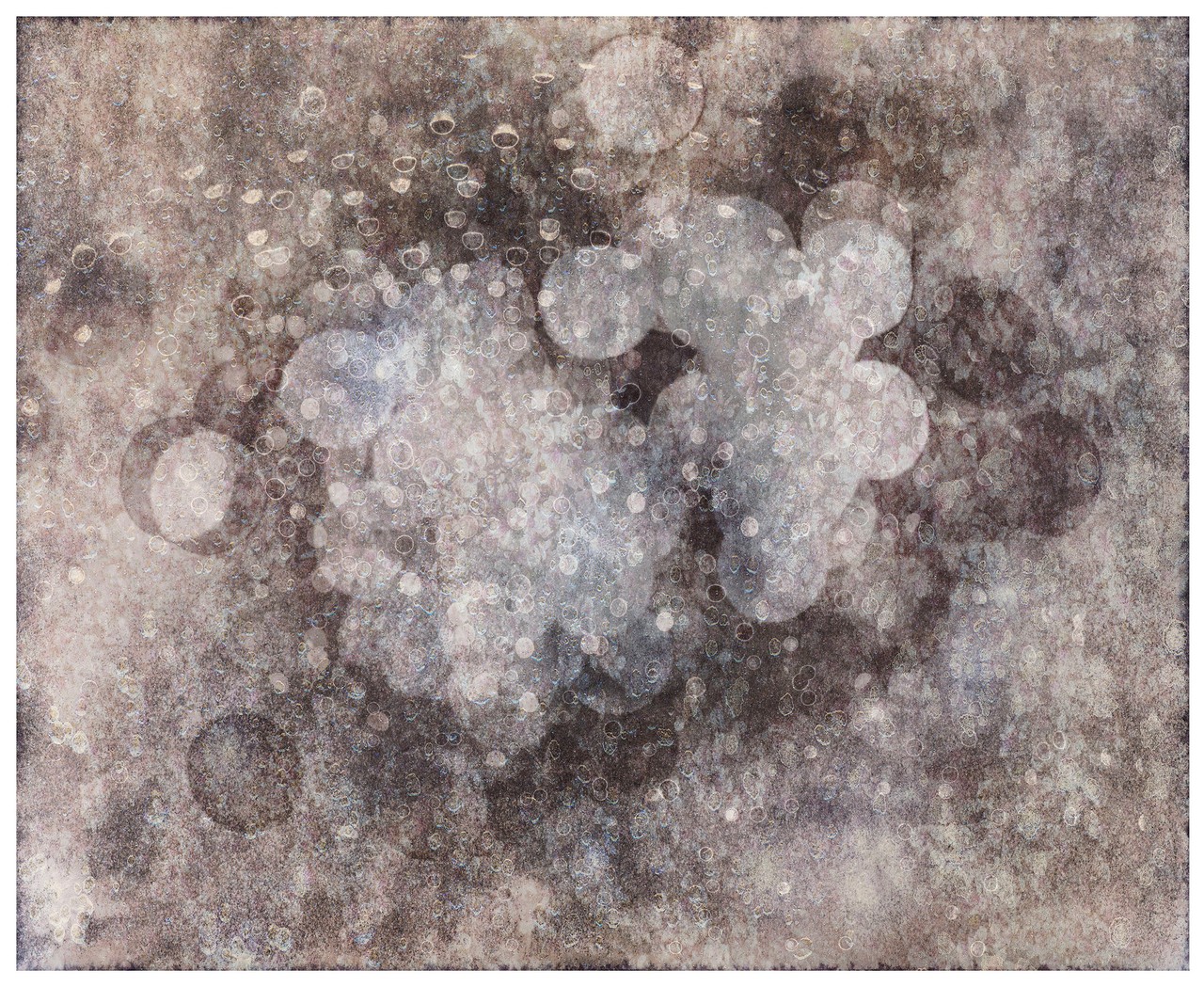

Thomas Brummett: Infinities #3

2013, Pure cotton paper printed with 100 year archival pigment ink, Ed. 3/5

91,5 x 120,4 cm / 36 x 47 1/2 in

Copyright: Thomas Brummett, Courtesy of Galerie Karsten Greve

2013, Pure cotton paper printed with 100 year archival pigment ink, Ed. 3/5

91,5 x 120,4 cm / 36 x 47 1/2 in

Copyright: Thomas Brummett, Courtesy of Galerie Karsten Greve

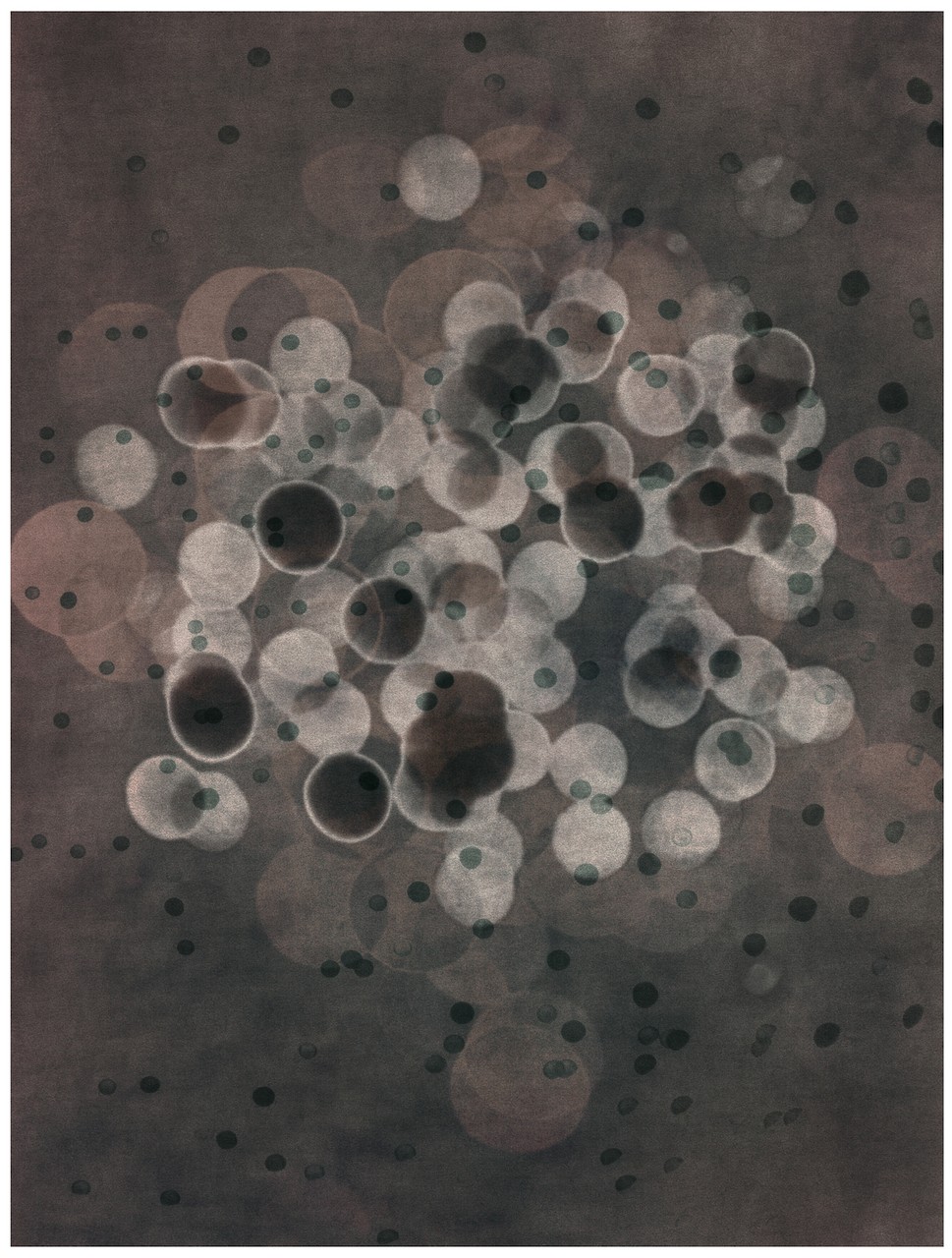

Thomas Brummett: Light Projection Variation #2

2013, Pure cotton paper printed with 100 year archival pigment ink, Ed. 3/5

117 x 91,5 cm / 46 x 36 in

Copyright: Thomas Brummett, Courtesy of Galerie Karsten Greve

2013, Pure cotton paper printed with 100 year archival pigment ink, Ed. 3/5

117 x 91,5 cm / 46 x 36 in

Copyright: Thomas Brummett, Courtesy of Galerie Karsten Greve

Thomas Brummett is an artist who is on a journey that follows two intertwined paths. Thoughtful and patient, he is on a quest to discover the essence of the natural world by focusing on the immediate before him—a twig, a fleeing light beam. He is also an explorer of the medium of photography, experimenting with the myriad ways of making an image with light and marks on the surface of light sensitive paper. All Brummett’s work is from his life-long series Rethinking the Natural.

Born in Colorado in 1955, Brummett matured with an appreciation of arid deserts and soaring mountains. He was educated in ceramics and photography at the Colorado State University (BFA, 1979) and the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, (MFA, 1982), after which he settled in Philadelphia and had a daughter. Raised in a Christian (Episcopalian) family that includes several members of the clergy, after reaching adulthood and traveling to India and Asia, Brummett found that the journey described in Western Abrahamic religions had lost its meaning for him, and he was drawn to Eastern Taoist/Buddhist theology. Rather than embarking on a pil-grimage of transcendence to a Deity who resides above and independent from the universe, Brummett found himself following Eastern monastic traditions that embark on a journey of immanence—intense observation of the world at hand. Such intense focus on the immediate resonates with the scientific method, and thus it is not surprising that Taoist/Buddhist thought permeates modern science and mathematics, as in the writings of Austri-an logician Ludwig Wittgenstein who wrote: “the place I must get to is the place where I already am” (Culture and Value, 1930). This mix of meditative practices and modern science is a thread running through Brummett’s art.

The parallel paths of the artist’s journey are clearly manifest in the series Infinities and Light Projections. In the series Light Projections the artist controlled the “circles of confusion” a lens can produce when out of focus. A “circle of confusion” is a term in optics for pinpoints of light (commonly known as bokeh [from the Japanese for “blur”]), which is an artifact of the lens that the artist describes as “an optical effect a lens produces with out of focus.” Brummett’s method of controlling and making images out of these so-called “circles of confusion” has never been done in the history of photography. According to the artist, the prints in this series “represent the physical manifestation of Light = The Infinite.” As the artist has stated: “The Light Projections for me are the perfect visual symbol of the Infinite. All light is a part of the natural world. Light is the very basis of the natu-ral world and all life and energy. [In this series] I was not shifting my attention away from the natural world but to its very essence. I was taking the natural world down to its purest form—Light.” With these words, Brummett is following in the footsteps of mystics throughout the ages who have associated light with infinity, and given these concepts divine associations. Notice that Brummett capitalizes “Light” and “the Infinite”, thus personifying/deifying them in the classical Greek tradition of “the Good” “the Just” and “the Triangle” which were, according to Plato, all divine. This association of light, infinity and divinity took deep root in Western thought.

An amateur astronomer can easily arrange to photograph through a ground-based telescope, but a non-scientist cannot book time on a telescope that orbits above earth’s atmosphere. So for photographs of outer space, Brummett used images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope that NASA makes available to the public. Starting with one of these recordings of light—a transatmospheric look back in time—the artist worked like a printmak-er and manipulated the image, desaturating the hue and layering the image with other patterns, all of which he has photographed from nature (Infinities [of Earth and Heaven] series 2013-16). The layers include images of stars, magnolia trees, a recording of snowflakes hitting a scanner, as well as real dust and mold from the artist’s studio. In these images Brummett describes his intention as to recreate William Blake’s idea of what the world would look like to all of us: “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, Infinite” (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1793).

Borrowing a term from thermodynamics, the artist calls his darkroom development process “entropic” (transfer of energy): “I print the image down to black and then resurrect it with bleaches, brushes and a redevelopment process. Each image is unique because the process is so naturally random.

The bleaches attack the metal in the paper literally eating it away.” The process is entropic because “the silver atoms move from a very ordered state to a chaotic state of dissolution or fragmentation, which give me a very beautiful line or edge.”

(Excerpts from a text by Lynn Gamwell, 2016)

Born in Colorado in 1955, Brummett matured with an appreciation of arid deserts and soaring mountains. He was educated in ceramics and photography at the Colorado State University (BFA, 1979) and the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, (MFA, 1982), after which he settled in Philadelphia and had a daughter. Raised in a Christian (Episcopalian) family that includes several members of the clergy, after reaching adulthood and traveling to India and Asia, Brummett found that the journey described in Western Abrahamic religions had lost its meaning for him, and he was drawn to Eastern Taoist/Buddhist theology. Rather than embarking on a pil-grimage of transcendence to a Deity who resides above and independent from the universe, Brummett found himself following Eastern monastic traditions that embark on a journey of immanence—intense observation of the world at hand. Such intense focus on the immediate resonates with the scientific method, and thus it is not surprising that Taoist/Buddhist thought permeates modern science and mathematics, as in the writings of Austri-an logician Ludwig Wittgenstein who wrote: “the place I must get to is the place where I already am” (Culture and Value, 1930). This mix of meditative practices and modern science is a thread running through Brummett’s art.

The parallel paths of the artist’s journey are clearly manifest in the series Infinities and Light Projections. In the series Light Projections the artist controlled the “circles of confusion” a lens can produce when out of focus. A “circle of confusion” is a term in optics for pinpoints of light (commonly known as bokeh [from the Japanese for “blur”]), which is an artifact of the lens that the artist describes as “an optical effect a lens produces with out of focus.” Brummett’s method of controlling and making images out of these so-called “circles of confusion” has never been done in the history of photography. According to the artist, the prints in this series “represent the physical manifestation of Light = The Infinite.” As the artist has stated: “The Light Projections for me are the perfect visual symbol of the Infinite. All light is a part of the natural world. Light is the very basis of the natu-ral world and all life and energy. [In this series] I was not shifting my attention away from the natural world but to its very essence. I was taking the natural world down to its purest form—Light.” With these words, Brummett is following in the footsteps of mystics throughout the ages who have associated light with infinity, and given these concepts divine associations. Notice that Brummett capitalizes “Light” and “the Infinite”, thus personifying/deifying them in the classical Greek tradition of “the Good” “the Just” and “the Triangle” which were, according to Plato, all divine. This association of light, infinity and divinity took deep root in Western thought.

An amateur astronomer can easily arrange to photograph through a ground-based telescope, but a non-scientist cannot book time on a telescope that orbits above earth’s atmosphere. So for photographs of outer space, Brummett used images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope that NASA makes available to the public. Starting with one of these recordings of light—a transatmospheric look back in time—the artist worked like a printmak-er and manipulated the image, desaturating the hue and layering the image with other patterns, all of which he has photographed from nature (Infinities [of Earth and Heaven] series 2013-16). The layers include images of stars, magnolia trees, a recording of snowflakes hitting a scanner, as well as real dust and mold from the artist’s studio. In these images Brummett describes his intention as to recreate William Blake’s idea of what the world would look like to all of us: “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, Infinite” (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1793).

Borrowing a term from thermodynamics, the artist calls his darkroom development process “entropic” (transfer of energy): “I print the image down to black and then resurrect it with bleaches, brushes and a redevelopment process. Each image is unique because the process is so naturally random.

The bleaches attack the metal in the paper literally eating it away.” The process is entropic because “the silver atoms move from a very ordered state to a chaotic state of dissolution or fragmentation, which give me a very beautiful line or edge.”

(Excerpts from a text by Lynn Gamwell, 2016)