Toasted Angels, Sounds Of Steel

Estate of León Ferrari

23 Nov 2019 - 01 Feb 2020

TOASTED ANGELS, SOUNDS OF STEEL

Estate of León Ferrari

23 Novmber – 1 February 2020

„The only thing I ask of art is that it helps me (...) to invent visual and critical signs that let me condemn more efficiently the barbarism of the West.“

León Ferrari, 1965

Earthworms are making themselves at home in the White House. They wiggle their way into the Oval Office and the private apartments, dangle from the flagpole on the roof, smear the star-spangled banner with their slime. Yuck. Sweet. Our exhibition opens with the video Casa Blanca, created in 2005. The desecration of a proud symbol? The defilement of an icon? Blasphemy? Whatever was León Ferrari thinking?

Ferrari did what he could. What he couldn’t do he didn’t. That sounds more banal than it is. For what Ferrari did was closely bound up with the political developments since the 1950s, for which he time and again found his own language, with the means at his disposal. A language—several languages—that breached the confines of the private sphere to go public and tell stories of war and tyranny, harassment, and freedom. Ferrari's artistic career began in 1955, the first year of the Vietnam War. For six decades, he traced the history of Western civilization as a history of globalized institutional violence. When León Ferrari died in his hometown of Buenos Aires in 2013 at the age of 93, he had long since become one of the great international voices of the Latin American continent.

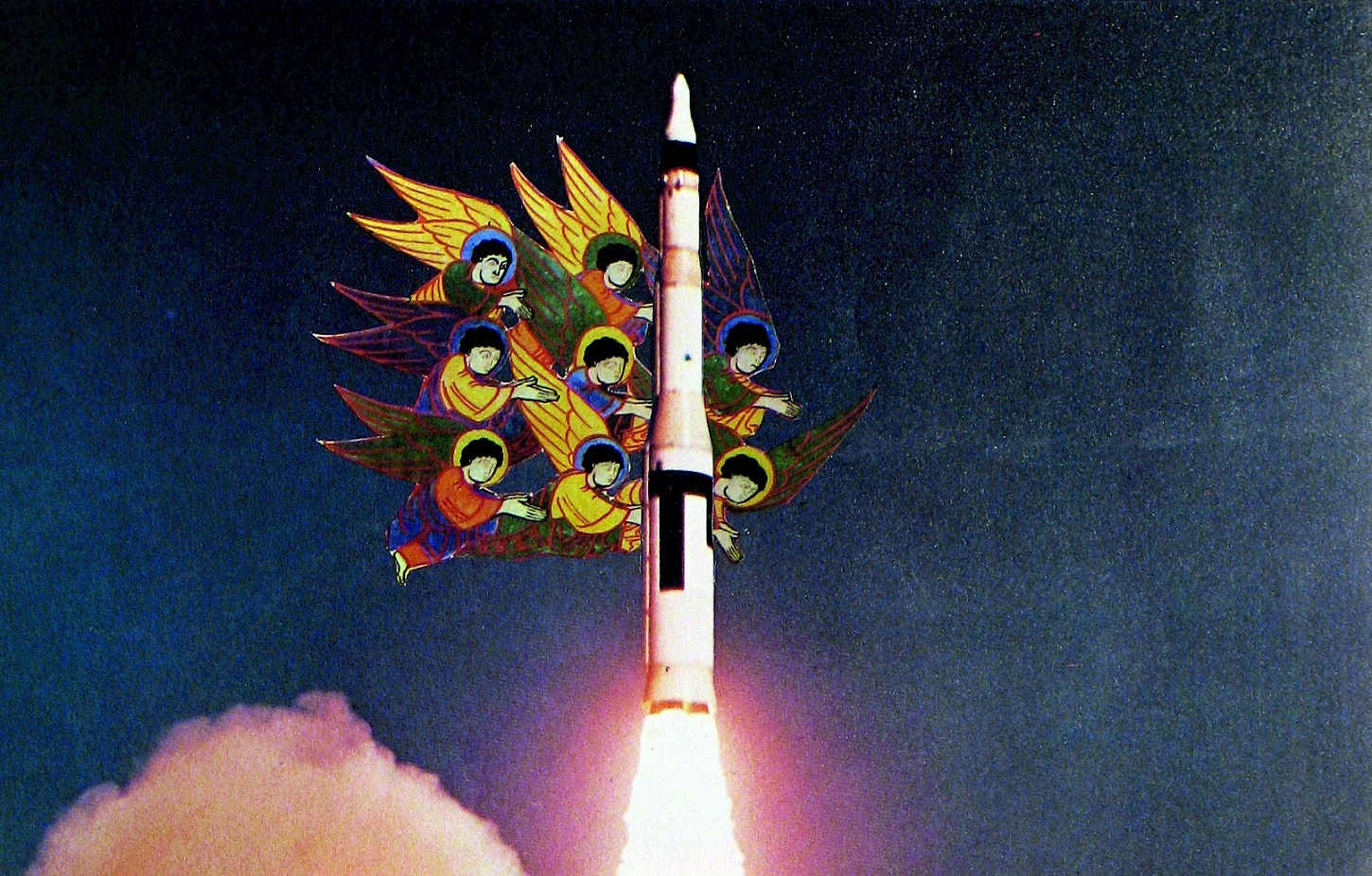

KOW presents a selective overview of his influential oeuvre, which has received too little attention in Germany. Even a cursory glance reveals that Ferrari had an axe to grind with the Catholic Church. His most famous and surely most controversial piece, La Civilización Occidental y Cristiana (1965), shows a painted-wood Jesus figure crucified to the replica of an American fighter jet from the Vietnam War. The work got him in trouble with the government, the Vatican, museums, but in the end it prevailed. We present previously unpublished collages from the 1980s which follow on from La Civilizacíon ... The works from the cycle Relecturas de la Biblia may provoke strong feelings even today: Nazi terror meets Catholic propaganda, combat tanks and long-range missiles protected by angels, the clergy at the Vatican contemplating the Holocaust as though it were a Last Judgment with God’s blessing, regimes of military and religious power hand in hand in the same picture. A hell on earth—forged of steel tubes, cyanide, and glorioles.

Objects from the late 2000s bring this anticlerical iconography of violence up to date in almost comedic fashion. With figures of saints in blenders, toasters, and preserve jars flanked by military equipment embellished with colorful feathers, Ferrari has devised a popular imagery that defies his subject’s all-too-human gravitas. He underscores how profoundly the history of the Occident, and of his native Argentina in particular, has been shaped by the Church’s missionary abuses, by a hegemonic canon of Western articles of faith that arrived with gunfire, was buttressed by dollars, and is overdue for the mincer.

A look back. March 1976. The military junta takes control of Argentina. Until 1983, the dictatorial regime disappears, tortures, and kills an estimated 30,000 people, with the tacit support of the United States and, to some extent, the Federal Republic of Germany. Ferrari’s son is among those who vanish without a trace. Ferrari goes in search of him, leaves Argentina for exile in Brazil, in São Paulo, lying low for a while to gather the strength he needs to keep going. He soon renders the megalopolis as a vast structure forcibly imposing antlike conformity, finds modern forms to articulate the modern city’s encroachments upon the individual—and begins making affordable reproductions of his works, circulates unlimited editions, looks for ways to democratize artistic production. In the late 1980s, he gradually moves his life back to Buenos Aires.

Ferrari’s iconoclastic and overtly more political work exists side by side with sculptures, lithographs, and drawings created over the course of several decades that speak in a more abstract and conceptual formal idiom. We showcase two of his minimalist steel sculptures, which he developed in the late seventies. Dozens of vertical metal rods can be set in motion and made to sound by visitors. The sculpture becomes a musical instrument that can be played together with several hands. Early drawings and late prints take up these filigree movements, translating them into a diction of lines and nodal points. Dating from the 1960s, these works seem to anticipate the hypertextuality of the internet age, but they also suggest a concrete poetry charting the space between word, writing, and gesture, reading now as anarchic expression without literal meaning, now as pamphlets.

Perhaps no less important than Ferrari’s output was his presence as a moral authority and lifelong mentor to many of his fellow artists. Walking into a bar or an alternative cultural center in Buenos Aires, a visitor today may well stumble across one of his sculptures that he set down years ago and never picked up. His art did not stop at the door of his studio, and his political activities were not limited to his own production. He designed covers for newspapers and magazines that offered critical takes on social realities, directed stage plays, wrote essays, gave interviews. León Ferrari’s estate is now managed by his family. His heirs seek to honor the progressive humanism that was the mainspring of his work and keep it alive for the future.

Text: Alexander Koch / Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Estate of León Ferrari

23 Novmber – 1 February 2020

„The only thing I ask of art is that it helps me (...) to invent visual and critical signs that let me condemn more efficiently the barbarism of the West.“

León Ferrari, 1965

Earthworms are making themselves at home in the White House. They wiggle their way into the Oval Office and the private apartments, dangle from the flagpole on the roof, smear the star-spangled banner with their slime. Yuck. Sweet. Our exhibition opens with the video Casa Blanca, created in 2005. The desecration of a proud symbol? The defilement of an icon? Blasphemy? Whatever was León Ferrari thinking?

Ferrari did what he could. What he couldn’t do he didn’t. That sounds more banal than it is. For what Ferrari did was closely bound up with the political developments since the 1950s, for which he time and again found his own language, with the means at his disposal. A language—several languages—that breached the confines of the private sphere to go public and tell stories of war and tyranny, harassment, and freedom. Ferrari's artistic career began in 1955, the first year of the Vietnam War. For six decades, he traced the history of Western civilization as a history of globalized institutional violence. When León Ferrari died in his hometown of Buenos Aires in 2013 at the age of 93, he had long since become one of the great international voices of the Latin American continent.

KOW presents a selective overview of his influential oeuvre, which has received too little attention in Germany. Even a cursory glance reveals that Ferrari had an axe to grind with the Catholic Church. His most famous and surely most controversial piece, La Civilización Occidental y Cristiana (1965), shows a painted-wood Jesus figure crucified to the replica of an American fighter jet from the Vietnam War. The work got him in trouble with the government, the Vatican, museums, but in the end it prevailed. We present previously unpublished collages from the 1980s which follow on from La Civilizacíon ... The works from the cycle Relecturas de la Biblia may provoke strong feelings even today: Nazi terror meets Catholic propaganda, combat tanks and long-range missiles protected by angels, the clergy at the Vatican contemplating the Holocaust as though it were a Last Judgment with God’s blessing, regimes of military and religious power hand in hand in the same picture. A hell on earth—forged of steel tubes, cyanide, and glorioles.

Objects from the late 2000s bring this anticlerical iconography of violence up to date in almost comedic fashion. With figures of saints in blenders, toasters, and preserve jars flanked by military equipment embellished with colorful feathers, Ferrari has devised a popular imagery that defies his subject’s all-too-human gravitas. He underscores how profoundly the history of the Occident, and of his native Argentina in particular, has been shaped by the Church’s missionary abuses, by a hegemonic canon of Western articles of faith that arrived with gunfire, was buttressed by dollars, and is overdue for the mincer.

A look back. March 1976. The military junta takes control of Argentina. Until 1983, the dictatorial regime disappears, tortures, and kills an estimated 30,000 people, with the tacit support of the United States and, to some extent, the Federal Republic of Germany. Ferrari’s son is among those who vanish without a trace. Ferrari goes in search of him, leaves Argentina for exile in Brazil, in São Paulo, lying low for a while to gather the strength he needs to keep going. He soon renders the megalopolis as a vast structure forcibly imposing antlike conformity, finds modern forms to articulate the modern city’s encroachments upon the individual—and begins making affordable reproductions of his works, circulates unlimited editions, looks for ways to democratize artistic production. In the late 1980s, he gradually moves his life back to Buenos Aires.

Ferrari’s iconoclastic and overtly more political work exists side by side with sculptures, lithographs, and drawings created over the course of several decades that speak in a more abstract and conceptual formal idiom. We showcase two of his minimalist steel sculptures, which he developed in the late seventies. Dozens of vertical metal rods can be set in motion and made to sound by visitors. The sculpture becomes a musical instrument that can be played together with several hands. Early drawings and late prints take up these filigree movements, translating them into a diction of lines and nodal points. Dating from the 1960s, these works seem to anticipate the hypertextuality of the internet age, but they also suggest a concrete poetry charting the space between word, writing, and gesture, reading now as anarchic expression without literal meaning, now as pamphlets.

Perhaps no less important than Ferrari’s output was his presence as a moral authority and lifelong mentor to many of his fellow artists. Walking into a bar or an alternative cultural center in Buenos Aires, a visitor today may well stumble across one of his sculptures that he set down years ago and never picked up. His art did not stop at the door of his studio, and his political activities were not limited to his own production. He designed covers for newspapers and magazines that offered critical takes on social realities, directed stage plays, wrote essays, gave interviews. León Ferrari’s estate is now managed by his family. His heirs seek to honor the progressive humanism that was the mainspring of his work and keep it alive for the future.

Text: Alexander Koch / Translation: Gerrit Jackson