Jiří Kovanda

27 Feb - 04 Apr 2013

JIŘÍ KOVANDA

27 Febraury - 4 April 2013

The objects and room installations developed by Jiří Kovanda consist of ordinary materials, which – at first glance – do not represent anything related to art and could be found anywhere. The presentation of the objects is adapted and precisely tailored to each individual exhibition space and not tied to one particular studio. Kovanda has been using his trademark mode of assemblage since the 1990s, when he began to assemble found objects (objets trouvés) from his personal surroundings or from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, ripping them from their original context. Kovanda’s objects function as surrogates for deficiencies in life, which are thus replaced by art. The common feature of the pieces presented at the Krobath Gallery is that each comes with a pedestal, like those used in museums. However, they are not intended to showcase and support the pieces; rather, they are artworks in their own right.

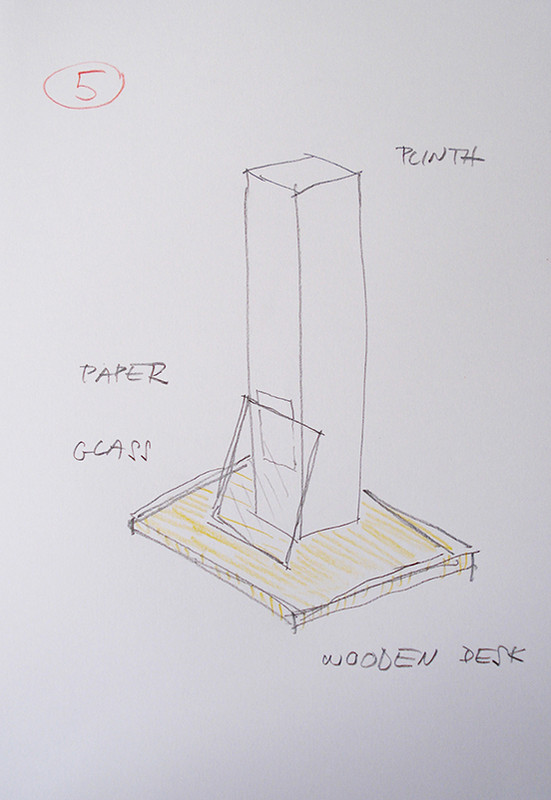

By combining various objects as auxiliary elements with the pedestals, Kovanda transforms them into pieces of art. These elements include wooden boards, paper, glass, a chair, a shirt, a leave, toy cars and a book of love poems. There is an ironic relationship between the elements: the pedestals are not the auxiliary items; on the contrary, the elements and materials support the pedestals. One exhibit, for example, comprises a shirt spread on the floor in the middle of the gallery, its sleeves pressed down by two pedestals. On the one hand, the pedestals are pinning down the shirt; on the other, the sleeves are underpinning the pedestals. Kovanda thus infringes the rules of conventional exhibition logic and explores physical limits. The other four pedestals in the exhibition are also supported by various objects: toy cars functioning as bearers, a chair or wooden boards.

The way Kovanda’s objects are assembled evokes a longing or desire for something new or different. From a psychoanalytical point of view, his objects produce a psychological urge to rectify a subjectively perceived deficiency and a compulsive desire to acquire new objects or create new states in order to compensate for the deficiency. This definition also corresponds to Kovanda’s understanding of art. According to Jacques Lacan’s theory, a compulsive desire also implies a sexual desire – Kovanda addresses this by including the book of love poems. It is rarely possible to fulfil the longing for vicarious objects to replace the deficiencies – a fact that is illustrated by the fragile pedestal objects, which hold their particular or oblique positions only with the support of other objects and would not function as individual objects in this spatial constellation. The disturbance caused by these objects amplifies the artistic potential of Kovanda, who used subtle performances to create confusion in everyday situations in the 1970s and today employs his art objects to provoke unease in an exhibition context.

Walter Seidl

(English translation: Mandana Taban)

27 Febraury - 4 April 2013

The objects and room installations developed by Jiří Kovanda consist of ordinary materials, which – at first glance – do not represent anything related to art and could be found anywhere. The presentation of the objects is adapted and precisely tailored to each individual exhibition space and not tied to one particular studio. Kovanda has been using his trademark mode of assemblage since the 1990s, when he began to assemble found objects (objets trouvés) from his personal surroundings or from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, ripping them from their original context. Kovanda’s objects function as surrogates for deficiencies in life, which are thus replaced by art. The common feature of the pieces presented at the Krobath Gallery is that each comes with a pedestal, like those used in museums. However, they are not intended to showcase and support the pieces; rather, they are artworks in their own right.

By combining various objects as auxiliary elements with the pedestals, Kovanda transforms them into pieces of art. These elements include wooden boards, paper, glass, a chair, a shirt, a leave, toy cars and a book of love poems. There is an ironic relationship between the elements: the pedestals are not the auxiliary items; on the contrary, the elements and materials support the pedestals. One exhibit, for example, comprises a shirt spread on the floor in the middle of the gallery, its sleeves pressed down by two pedestals. On the one hand, the pedestals are pinning down the shirt; on the other, the sleeves are underpinning the pedestals. Kovanda thus infringes the rules of conventional exhibition logic and explores physical limits. The other four pedestals in the exhibition are also supported by various objects: toy cars functioning as bearers, a chair or wooden boards.

The way Kovanda’s objects are assembled evokes a longing or desire for something new or different. From a psychoanalytical point of view, his objects produce a psychological urge to rectify a subjectively perceived deficiency and a compulsive desire to acquire new objects or create new states in order to compensate for the deficiency. This definition also corresponds to Kovanda’s understanding of art. According to Jacques Lacan’s theory, a compulsive desire also implies a sexual desire – Kovanda addresses this by including the book of love poems. It is rarely possible to fulfil the longing for vicarious objects to replace the deficiencies – a fact that is illustrated by the fragile pedestal objects, which hold their particular or oblique positions only with the support of other objects and would not function as individual objects in this spatial constellation. The disturbance caused by these objects amplifies the artistic potential of Kovanda, who used subtle performances to create confusion in everyday situations in the 1970s and today employs his art objects to provoke unease in an exhibition context.

Walter Seidl

(English translation: Mandana Taban)