Ursula Mayer

30 Apr - 05 Jun 2014

URSULA MAYER

30 April - 5 June 2014

Ursula Mayer’s artistic manifestations deal with cross-gender body concepts, which she analyses against a backdrop of cultural references. Be it in film, photography, performance or installation, Mayer’s works focus on the fluidity of bodily dimensions and the resulting disintegration of traditional ideas of physicality.

The rejection of clear attributions of post-feminist body definitions and functions are reminiscent of Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto, in which she considers the social construction of the female in the late 20th century as a chimera, a theoretical and fabricated hybrid of machine and organism. Haraway’s cyborgs have no defined gender and therefore exist beyond hierarchies – this brings about new opportunities for emancipation. According to Haraway, cyborgs evoke a post-gender debate in a world of imagination and materiality/object-relatedness. In her photo series “The Unbegotten” (2013) Mayer alludes to this idea and depicts sculptures by Bruno Gironcoli that define the shape of the models’ bodies. The combination of machine and organism gives rise to questions about their object nature and fluidity – when the cyborgs resurrect after being melt into a hot, fluid aggregate phase, for example.

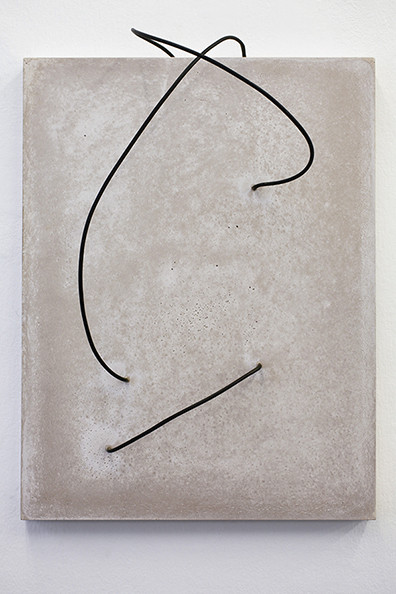

Ursula Mayer’s current exhibition in the Krobath Gallery takes visitors into a world of objects whose fluidity has been made visible, although they dominate the gallery space in solid form. The works draw on Graham Harman’s theory of object-oriented ontology (OOO), which views all forms of existence as constellations of objects. According to Harman there are two categories of objects: real objects and sensual or intentional objects. The latter correlate with Mayer’s works, where objects represent thoughts and imagination, thus also alluding to Haraway’s theories. In his theory, Harman also develops a metaphysical realism that releases objects from their human captivity and presents them in isolation. This also applies to Mayer’s objects, which extricate bodies from their pre-formulated identity in society. In line with Heraclitus’ philosophy “Panta Rhei” –“everything flows”– Mayer does not consider beings as static constructs, instead emphasising the dynamics of a constant transition.

The exhibition at the Krobath Gallery presents amorphous glass objects, some of which were already displayed under the title “Visceral Flowers” in Mayer’s solo exhibition at 21er Haus in Vienna. The “visceral” aspect brings to mind organs which determine the shape of objects, but it can also be interpreted as the remnants of melted cyborgs. What remains is an undefined surface symbolising the various formations of the medium of skin, which is often economically determined and also (re)produces technological surfaces. Mayer thus draws on Foucault’s biopolitics, which describes humans as a group that is dominated by biological processes and laws. Biopower relates to the regulation and organisation of life. Whether as individuals or in collectives, humans learn to use and modify their bodies to adapt to specific spaces. In a similar manner, Haraway’s studies of concepts of bodily limitations and social order lead to an awareness of how body metaphors refer to a certain worldview and a political discourse and patriarchal capitalism. In her works, Mayer addresses the fragmentation resulting from this discrepancy between the social and individual organisation of the body – a fragmentation that manifests itself in various forms of performance that go beyond a predetermined gender matrix.

Walter Seidl

(English translation: Mandana Taban)

30 April - 5 June 2014

Ursula Mayer’s artistic manifestations deal with cross-gender body concepts, which she analyses against a backdrop of cultural references. Be it in film, photography, performance or installation, Mayer’s works focus on the fluidity of bodily dimensions and the resulting disintegration of traditional ideas of physicality.

The rejection of clear attributions of post-feminist body definitions and functions are reminiscent of Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto, in which she considers the social construction of the female in the late 20th century as a chimera, a theoretical and fabricated hybrid of machine and organism. Haraway’s cyborgs have no defined gender and therefore exist beyond hierarchies – this brings about new opportunities for emancipation. According to Haraway, cyborgs evoke a post-gender debate in a world of imagination and materiality/object-relatedness. In her photo series “The Unbegotten” (2013) Mayer alludes to this idea and depicts sculptures by Bruno Gironcoli that define the shape of the models’ bodies. The combination of machine and organism gives rise to questions about their object nature and fluidity – when the cyborgs resurrect after being melt into a hot, fluid aggregate phase, for example.

Ursula Mayer’s current exhibition in the Krobath Gallery takes visitors into a world of objects whose fluidity has been made visible, although they dominate the gallery space in solid form. The works draw on Graham Harman’s theory of object-oriented ontology (OOO), which views all forms of existence as constellations of objects. According to Harman there are two categories of objects: real objects and sensual or intentional objects. The latter correlate with Mayer’s works, where objects represent thoughts and imagination, thus also alluding to Haraway’s theories. In his theory, Harman also develops a metaphysical realism that releases objects from their human captivity and presents them in isolation. This also applies to Mayer’s objects, which extricate bodies from their pre-formulated identity in society. In line with Heraclitus’ philosophy “Panta Rhei” –“everything flows”– Mayer does not consider beings as static constructs, instead emphasising the dynamics of a constant transition.

The exhibition at the Krobath Gallery presents amorphous glass objects, some of which were already displayed under the title “Visceral Flowers” in Mayer’s solo exhibition at 21er Haus in Vienna. The “visceral” aspect brings to mind organs which determine the shape of objects, but it can also be interpreted as the remnants of melted cyborgs. What remains is an undefined surface symbolising the various formations of the medium of skin, which is often economically determined and also (re)produces technological surfaces. Mayer thus draws on Foucault’s biopolitics, which describes humans as a group that is dominated by biological processes and laws. Biopower relates to the regulation and organisation of life. Whether as individuals or in collectives, humans learn to use and modify their bodies to adapt to specific spaces. In a similar manner, Haraway’s studies of concepts of bodily limitations and social order lead to an awareness of how body metaphors refer to a certain worldview and a political discourse and patriarchal capitalism. In her works, Mayer addresses the fragmentation resulting from this discrepancy between the social and individual organisation of the body – a fragmentation that manifests itself in various forms of performance that go beyond a predetermined gender matrix.

Walter Seidl

(English translation: Mandana Taban)