Deana Lawson

Centropy

09 Jun - 11 Oct 2020

DEANA LAWSON

Centropy

9 June – 11 October 2020

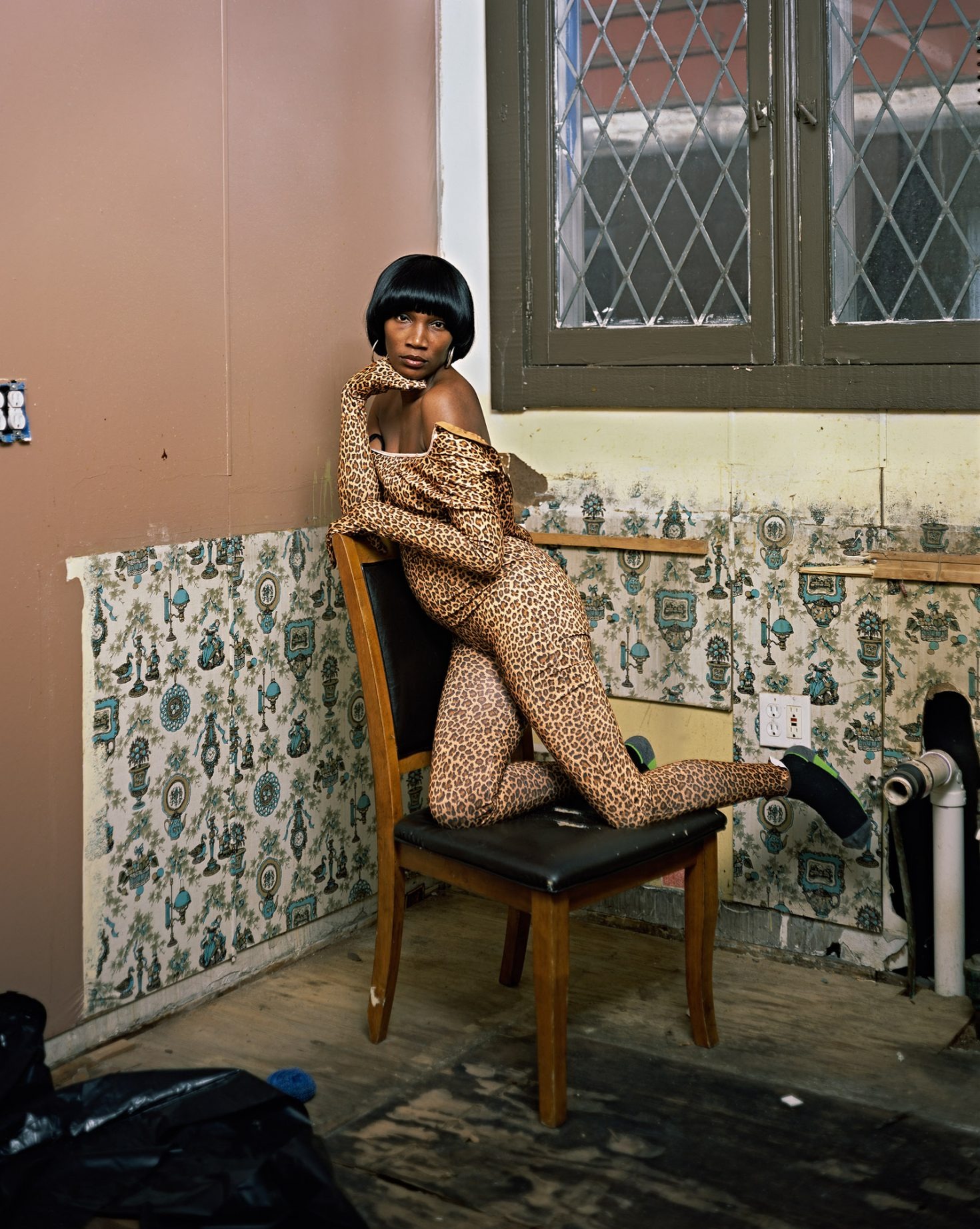

Deana Lawson is creating a family among strangers. She happens upon them in a lush Jamaican field, a Brazilian favela, or a

children’s clothing store in the Bronx. She’ll scout out her own neighborhood or travel the world, to wherever the African diaspora emanates from or was exiled to, struck by someone’s presence or style, by a bodily curve, facial scar, or hairdo. In

these strangers, she recognizes what she calls “godlike beings.” One by one, she will convince them to allow her in: into their

homes, with all their love-worn particulari- ties, but also into their lives. There is a conspiratorial intimacy that enables her to

capture the subjects of her photographs as regal, commanding, supremely sensual, and very much of the here and now, while also seeming to channel past lives of stately sovereignty. Even if these often are, in fact, highly staged compositions, Lawson’s grip- ping portraits of contemporary Black life are no less candid, intimate, or real because of it.

One critic aptly called them “manipulated vérité.” Which is to say that hers is a form of documentary photography in which

art history, portraiture traditions, vernacular culture, and colonial legacies meet. Perhaps it couldn’t have turned out otherwise for Lawson, who was reared at the fulcrum of late modernity’s most popular visual technologies. Her father, the family photographer, worked for Xerox and her mother for Kodak in Rochester, New York, US, where Lawson grew up. Her grandmother cleaned the home of George Eastman, founder of the camera and film empire. Articles on the artist frequently recount these biographical details, suggesting that it might have been Lawson’s inevitable destiny to become a photographer. Just as important to this narrative, however, is how her deep-seated connection to the medium also compelled a thorough exposure to the skewed representations of Black subjects within dominant photographic histories (either not represented at all or cast in all-too-narrow roles): So different were these mainstream representations from those seen in the workingclass homes of Lawson’s friends and family, where men, women, and children appeared in personal photographs—not as stereotypes or stand-ins for a sociological category, but as themselves: fully, complexly, mysteriously, and triumphantly.

As activist and writer bell hooks understood: “Cameras gave black folks, irrespective of class, a means by which we could participate fully in the production of images... to create a counter-hegemonic world of images that would stand as visual resistance, challenging racist images.” It is Lawson’s keen, profoundlyingrained understanding of this technology’s power, and her response to it, that actuates a potent complexity: full of tenderness, her images exalt an everyday Black vernacular

while not glossing over the fact that if one is talking about race, one inevitably also has to address class. Novelist Zadie Smith recog- nized this in Lawson’s images, with their “half-painted walls, faulty wiring, sheetless mattresses, cardboard boxes filled with old-format technology, beat-up couches, frayed rugs, curling tiles, broken blinds... That these circumstances should prove so similar—from New York to Jamaica, from Haiti to the Democratic Republic of the Congo—carries its own political message.” And still, as in so much of Lawson’s portraiture, Blackness is an identity that is neither monolithic nor can it be understood apart from the passage, flight, and migration forced by a dominant white system that has dispersed people of color across the globe.

For her exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, the first presentation in Switzerland and the largest institutional exhibition of her work

to date, Lawson presents new and recent works, including a body of large-scale photo- graphs, holograms, 16mm films, a video, and several installations of small snapshot images, some printed on mirrors and bor- dered by crystal-encrusted mirrors. Each of the large-scale photographic works is set in an opulent frame built from mirrored glass. That typically extraneous, negligible element—the picture frame—here takes on particular importance. Extravagant and elegant at once, Lawson’s frames (one example even accompanied by the verdant spectral glow of a hologram that is set into the image itself) further elevate the pictured sitters in a play of reflections and the sort of ricocheting light that connects her sub- jects to something mystical and magnificent, despite their modest life situations.

The resultant charge of her pictures is height- ened by the scale of the prints, most exceeding one meter in width: This has the effect of almost bodily inviting viewers into the nearly life-sized domestic spaces they picture, but also taunting you—as one review put it: You are invited in but not allowed to stay. “The way they look at you!” Zadie Smith exclaims, referring to a particular Lawson photograph (but it could be just about any of them), adding that in it she perceives “a gaze so intense that it’s the viewer who ends up feeling naked.” Think of this as you look at House of My Deceased Lover (2019), in which a young woman bal- ances, nude and knees bent, facing the camera on the bed of her dead partner. She is defiant and strong, unblinking. Small me- mentos (a prayer card, money, a snapshot of giant diamond bling) are tucked into the edges of this work, turning the whole into a kind of altar, and its protagonist (no matter how broken the wardrobe or how unmade the bed), into a goddess or saint, worthy of worship and devotion.

Or there is Axis (2018), in which three nudes lock eyes with you (somehow, strangely, even the one whose eyes are closed) as they lie on their sides, each pressed against the other on a rug inside someone’s home. The striking photograph recalls an art historical image you think you might have seen (but, in fact, never have), all while the lustrous skin and variegated beauty of the trio, resembling synchronized swimmers on dry land, fans out like a gradient of brown.

Taneisha’s Gravity (2019) features two women in the backroom of a church—Jacqueline, who is flamboyant and poised, aware of the camera’s every movement, and Taneisha, whose eyes and head cannot hold themselves open and upright. They are encoun- tered again in the 16mm films in the exhibition’s back rooms, in which the stillness of the photographic version suddenly comes to life, and where their flickering presence is seen beside a single, unframed hologram: Printed on glass and portraying an outdated sound system, it assumes the aura of an almost magical object from the recent past whose uncanny glow electrifies the muted paraphernalia of Black music culture.

Then there is Chief (2019), in which mis- matched curtains billow in a living room where a man solemnly sits on the edge

of a velveteen couch, bedecked in golden jewelry and a makeshift crown, his gaze unperturbed. Though resolute in his com- manding poise, his kingdom is perhaps not of this world or time. Lining the stained walls behind him are an icon depicting

Jesus and a tapestry of his Last Supper... depicting this king as white. It is a detail distilling the tensions that so much of Lawson’s work exposes.

The figure in Chief reappears in Lawson’s video, which incorporates historic and contemporary material, splicing found footage from the 1930s of Ethiopian military troops with contemporary African-American youth displaying coded gestures signifying gang affiliation or a celebration of the historic roots of the Ashanti and its golden bedecked rituals with the ostentatious bling of African-American hip-hop culture— these and other juxtapositions reveal disparate African cultures as connected by an invisible but indelible tether that binds them across time and space. It is the present embodiment of a past majesty that acts like a through line in the exhibition. Yet there is an acute sense that even the majestic (or perhaps especially the majestic) is under threat: Lawson admits that with so many having been separated through the transatlantic slave trade of previous eras, a history inextricable from the fact of so many Black lives being taken in our present, she chose

to line the exhibition’s main room with photographs of her family of strangers hung relatively “close together,” as she says, “for [their own] safety.”

Lawson gathers her ensemble under the title, Centropy, which resonates in peculiar ways in our present moment. If entropy speaks of the way things dissolve into chaos, centropy describes the opposite, the electrification of matter that leads to creative renewal and order. As this exhibition is being installed and is opening to the public, cities across the USA are ablaze with anger and indignation that yet another Black life was lost (after countless others) at the hands of the very people

and systems supposed to serve and protect them. The exhibition comes, moreover, in the midst of a global pandemic that dis- proportionately affects those whose race, class, or sexuality already puts them at a disadvantage and exposes them, once more, to a higher health and economic risk. In times like our own, Centropy’s message is all the more urgent. Indeed, especially at a moment when the vulnerability of the com- munities Lawson photographs is so tragically visible, her dignified and resplendent repre- sentations of Black lives urge us to not look away.

Deana Lawson was born 1979 in Rochester, New York, US; she lives and works in New York City, US.

Meticulously staged yet profoundly intimate images of the sartorial styles, quotidian habits, and domestic interiors of the African diaspora in her native United States, Brazil, and beyond, Deana Lawson’s (* 1979) photographs are unforgettable portraits of contemporary Black life.

Centropy

9 June – 11 October 2020

Deana Lawson is creating a family among strangers. She happens upon them in a lush Jamaican field, a Brazilian favela, or a

children’s clothing store in the Bronx. She’ll scout out her own neighborhood or travel the world, to wherever the African diaspora emanates from or was exiled to, struck by someone’s presence or style, by a bodily curve, facial scar, or hairdo. In

these strangers, she recognizes what she calls “godlike beings.” One by one, she will convince them to allow her in: into their

homes, with all their love-worn particulari- ties, but also into their lives. There is a conspiratorial intimacy that enables her to

capture the subjects of her photographs as regal, commanding, supremely sensual, and very much of the here and now, while also seeming to channel past lives of stately sovereignty. Even if these often are, in fact, highly staged compositions, Lawson’s grip- ping portraits of contemporary Black life are no less candid, intimate, or real because of it.

One critic aptly called them “manipulated vérité.” Which is to say that hers is a form of documentary photography in which

art history, portraiture traditions, vernacular culture, and colonial legacies meet. Perhaps it couldn’t have turned out otherwise for Lawson, who was reared at the fulcrum of late modernity’s most popular visual technologies. Her father, the family photographer, worked for Xerox and her mother for Kodak in Rochester, New York, US, where Lawson grew up. Her grandmother cleaned the home of George Eastman, founder of the camera and film empire. Articles on the artist frequently recount these biographical details, suggesting that it might have been Lawson’s inevitable destiny to become a photographer. Just as important to this narrative, however, is how her deep-seated connection to the medium also compelled a thorough exposure to the skewed representations of Black subjects within dominant photographic histories (either not represented at all or cast in all-too-narrow roles): So different were these mainstream representations from those seen in the workingclass homes of Lawson’s friends and family, where men, women, and children appeared in personal photographs—not as stereotypes or stand-ins for a sociological category, but as themselves: fully, complexly, mysteriously, and triumphantly.

As activist and writer bell hooks understood: “Cameras gave black folks, irrespective of class, a means by which we could participate fully in the production of images... to create a counter-hegemonic world of images that would stand as visual resistance, challenging racist images.” It is Lawson’s keen, profoundlyingrained understanding of this technology’s power, and her response to it, that actuates a potent complexity: full of tenderness, her images exalt an everyday Black vernacular

while not glossing over the fact that if one is talking about race, one inevitably also has to address class. Novelist Zadie Smith recog- nized this in Lawson’s images, with their “half-painted walls, faulty wiring, sheetless mattresses, cardboard boxes filled with old-format technology, beat-up couches, frayed rugs, curling tiles, broken blinds... That these circumstances should prove so similar—from New York to Jamaica, from Haiti to the Democratic Republic of the Congo—carries its own political message.” And still, as in so much of Lawson’s portraiture, Blackness is an identity that is neither monolithic nor can it be understood apart from the passage, flight, and migration forced by a dominant white system that has dispersed people of color across the globe.

For her exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, the first presentation in Switzerland and the largest institutional exhibition of her work

to date, Lawson presents new and recent works, including a body of large-scale photo- graphs, holograms, 16mm films, a video, and several installations of small snapshot images, some printed on mirrors and bor- dered by crystal-encrusted mirrors. Each of the large-scale photographic works is set in an opulent frame built from mirrored glass. That typically extraneous, negligible element—the picture frame—here takes on particular importance. Extravagant and elegant at once, Lawson’s frames (one example even accompanied by the verdant spectral glow of a hologram that is set into the image itself) further elevate the pictured sitters in a play of reflections and the sort of ricocheting light that connects her sub- jects to something mystical and magnificent, despite their modest life situations.

The resultant charge of her pictures is height- ened by the scale of the prints, most exceeding one meter in width: This has the effect of almost bodily inviting viewers into the nearly life-sized domestic spaces they picture, but also taunting you—as one review put it: You are invited in but not allowed to stay. “The way they look at you!” Zadie Smith exclaims, referring to a particular Lawson photograph (but it could be just about any of them), adding that in it she perceives “a gaze so intense that it’s the viewer who ends up feeling naked.” Think of this as you look at House of My Deceased Lover (2019), in which a young woman bal- ances, nude and knees bent, facing the camera on the bed of her dead partner. She is defiant and strong, unblinking. Small me- mentos (a prayer card, money, a snapshot of giant diamond bling) are tucked into the edges of this work, turning the whole into a kind of altar, and its protagonist (no matter how broken the wardrobe or how unmade the bed), into a goddess or saint, worthy of worship and devotion.

Or there is Axis (2018), in which three nudes lock eyes with you (somehow, strangely, even the one whose eyes are closed) as they lie on their sides, each pressed against the other on a rug inside someone’s home. The striking photograph recalls an art historical image you think you might have seen (but, in fact, never have), all while the lustrous skin and variegated beauty of the trio, resembling synchronized swimmers on dry land, fans out like a gradient of brown.

Taneisha’s Gravity (2019) features two women in the backroom of a church—Jacqueline, who is flamboyant and poised, aware of the camera’s every movement, and Taneisha, whose eyes and head cannot hold themselves open and upright. They are encoun- tered again in the 16mm films in the exhibition’s back rooms, in which the stillness of the photographic version suddenly comes to life, and where their flickering presence is seen beside a single, unframed hologram: Printed on glass and portraying an outdated sound system, it assumes the aura of an almost magical object from the recent past whose uncanny glow electrifies the muted paraphernalia of Black music culture.

Then there is Chief (2019), in which mis- matched curtains billow in a living room where a man solemnly sits on the edge

of a velveteen couch, bedecked in golden jewelry and a makeshift crown, his gaze unperturbed. Though resolute in his com- manding poise, his kingdom is perhaps not of this world or time. Lining the stained walls behind him are an icon depicting

Jesus and a tapestry of his Last Supper... depicting this king as white. It is a detail distilling the tensions that so much of Lawson’s work exposes.

The figure in Chief reappears in Lawson’s video, which incorporates historic and contemporary material, splicing found footage from the 1930s of Ethiopian military troops with contemporary African-American youth displaying coded gestures signifying gang affiliation or a celebration of the historic roots of the Ashanti and its golden bedecked rituals with the ostentatious bling of African-American hip-hop culture— these and other juxtapositions reveal disparate African cultures as connected by an invisible but indelible tether that binds them across time and space. It is the present embodiment of a past majesty that acts like a through line in the exhibition. Yet there is an acute sense that even the majestic (or perhaps especially the majestic) is under threat: Lawson admits that with so many having been separated through the transatlantic slave trade of previous eras, a history inextricable from the fact of so many Black lives being taken in our present, she chose

to line the exhibition’s main room with photographs of her family of strangers hung relatively “close together,” as she says, “for [their own] safety.”

Lawson gathers her ensemble under the title, Centropy, which resonates in peculiar ways in our present moment. If entropy speaks of the way things dissolve into chaos, centropy describes the opposite, the electrification of matter that leads to creative renewal and order. As this exhibition is being installed and is opening to the public, cities across the USA are ablaze with anger and indignation that yet another Black life was lost (after countless others) at the hands of the very people

and systems supposed to serve and protect them. The exhibition comes, moreover, in the midst of a global pandemic that dis- proportionately affects those whose race, class, or sexuality already puts them at a disadvantage and exposes them, once more, to a higher health and economic risk. In times like our own, Centropy’s message is all the more urgent. Indeed, especially at a moment when the vulnerability of the com- munities Lawson photographs is so tragically visible, her dignified and resplendent repre- sentations of Black lives urge us to not look away.

Deana Lawson was born 1979 in Rochester, New York, US; she lives and works in New York City, US.

Meticulously staged yet profoundly intimate images of the sartorial styles, quotidian habits, and domestic interiors of the African diaspora in her native United States, Brazil, and beyond, Deana Lawson’s (* 1979) photographs are unforgettable portraits of contemporary Black life.