Georgia Sagri

13 Apr - 08 Jun 2014

GEORGIA SAGRI

Mona Lisa Effect

13 April – 8 June 2014

The “Mona Lisa effect” is a term describing an optical and psychological effect produced by the famous painting by Leonardo da Vinci, now in the collection of the Louvre. Testifying to Leonardo’s mastery, the smiling Mona Lisa seems to follow us with her gaze as we move about the gallery – if we can move at all. For the painting itself, protected by bulletproof glass, two barriers and museum attendants, seems to have the power to transfix visitors in whatever spot they manage to find among the crowd, where their movements are limited to raising their arms and taking pictures.

Under the title “Mona Lisa Effect”, Georgia Sagri’s exhibition addresses the physical and political phenomenon of movement both inside and outside the gallery space, through a series of performative, rhetorical and technological devices that organize the exhibition space. This “movement” can further be understood as our natural human disposition (and right) to move, to gather and disperse, to convene and reconvene. In Sagri’s reading of the Mona Lisa effect, the gaze emanating from the masterpiece thus becomes a metaphor of the ever-surveying, ever-inspecting gaze of authority – the diffused political power that permeates human lives in contemporary society. This “soft” omnipresence of power has long since become an integral dimension of our lives as citizens: being a citizen today equals being subject to biopolitics, the form of power that impacts all aspects of human life, as the private and public sphere meld into an inseparable whole.

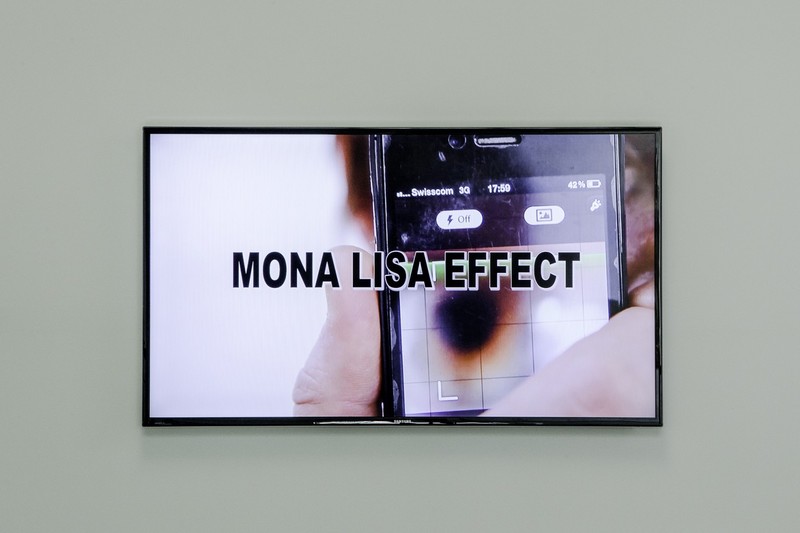

At the top of the stairs leading up to the Oberlichtsaal, a video playing on a flat screen serves as introduction, tutorial and manual to the exhibition. It has been produced as a sort of trailer, suggesting a range of possible actions that visitors will be able to perform or see once they enter the show.

A large wall divides the main gallery into two halves, with a gap at the right-hand end to allow visitors to proceed through the exhibition. The wall facing the arriving visitor is covered with wallpaper bearing a brickwork pattern. This fake brick wall evokes an outdoor space: a wall separates a building from the outside, thus establishing a boundary between the contained interior and the nominally public exterior. The red brick connotes factories of the early industrial era, as well as the simplest weapon used in city riots – the brick – or a place to post and spray-paint political messages. Looming over the pristine neoclassical gallery, the wall also alludes to the crudest forms of oppression, such as imprisonment and execution. Sagri has left the narrow end of her wall open, exposing its inner construction and hence the artificiality of the structure. The rear of the wall is plastered and remains white, thus creating a regular gallery space on this side of the wall.

During the exhibition, Sagri – wearing a specially created one-piece costume printed with a picture of her own body dressed in casual clothing – will perform specific movements in front of the wall and around its free corner. These will be divided into four sequences and performed at variable intervals in changing durations. The movement of the performer is organized from left to right along the wall, underlining the sequential, linear, proto-cinematic character of the performance: a build-up of suspense, action, culmination, and finally the repetition of the sequence.

White wall labels sparsely distributed in the galleries are placed at the height normally reserved for labels in a museum and imitate their design. We might imagine strolling through the gallery, looking at paintings or drawings, and then checking the title and date of the work, and the name of the artist. Here, however, the labels refer to things far away from the gallery space. Each label carries a name (of a person or collective body), date and a QR code – a type of barcode that can be read by software available as a free download for most mobile phones. By scanning the code, visitors instantly reach the content stored on the corresponding website. The show thus extends into several other settings and narrations. These range from video works commissioned by Sagri from fellow artists to pieces of music, essays and the websites of specific organizations (such as the artists’ collective CAGE and Embros, the occupied theatre in Athens that has played an important role as a venue for self-organized political and artistic activities in Athens during the recent economic crisis).

In the second gallery, a custom-made machine displays a panorama of a large photograph printed on PVC, continuously scrolling in one direction. The picture was taken in Exarcheia, a district of Athens considered an anarchist home base, on the site where a policeman shot 15-year-old student Alexis Grigoropoulos on the night of December 6, 2008. The riots that followed turned into a general protest against the systemic failure of the state, with its endemic social injustice and escalating poverty. It was the beginning of a confrontation between the government and the people that is still on-going today, and which addresses various concerns, takes different forms and involves a growing number of strategies of self-organization. Sagri’s panorama shows a wall covered with graffiti slogans that can be ascribed to several politically active dissident groups, along with two memorial plaques – one presented by the State and a smaller one installed by Grigoropoulos’s family and friends.

In the third gallery, a small Plexiglas box features a single coin – an American quarter that was placed on a train track and flattened to a thin, oval shape, similar to a guitar pick, with the face of George Washington strangely disfigured, and the words “liberty” and “in God we trust” barely legible. This violent transformation – from money to matter – seems to point to the possibility of larger-scale change and raises the hope that the current order of things is perhaps not as immutable as it appears.

Outside the Kunsthalle, at various locations in Basel, a series of posters presents photographs of the artist physically approaching paintings made in her studio. These photos are annotated with texts that obliquely refer to events that happened in the past, are happening now or will happen in the future.

Mona Lisa Effect

13 April – 8 June 2014

The “Mona Lisa effect” is a term describing an optical and psychological effect produced by the famous painting by Leonardo da Vinci, now in the collection of the Louvre. Testifying to Leonardo’s mastery, the smiling Mona Lisa seems to follow us with her gaze as we move about the gallery – if we can move at all. For the painting itself, protected by bulletproof glass, two barriers and museum attendants, seems to have the power to transfix visitors in whatever spot they manage to find among the crowd, where their movements are limited to raising their arms and taking pictures.

Under the title “Mona Lisa Effect”, Georgia Sagri’s exhibition addresses the physical and political phenomenon of movement both inside and outside the gallery space, through a series of performative, rhetorical and technological devices that organize the exhibition space. This “movement” can further be understood as our natural human disposition (and right) to move, to gather and disperse, to convene and reconvene. In Sagri’s reading of the Mona Lisa effect, the gaze emanating from the masterpiece thus becomes a metaphor of the ever-surveying, ever-inspecting gaze of authority – the diffused political power that permeates human lives in contemporary society. This “soft” omnipresence of power has long since become an integral dimension of our lives as citizens: being a citizen today equals being subject to biopolitics, the form of power that impacts all aspects of human life, as the private and public sphere meld into an inseparable whole.

At the top of the stairs leading up to the Oberlichtsaal, a video playing on a flat screen serves as introduction, tutorial and manual to the exhibition. It has been produced as a sort of trailer, suggesting a range of possible actions that visitors will be able to perform or see once they enter the show.

A large wall divides the main gallery into two halves, with a gap at the right-hand end to allow visitors to proceed through the exhibition. The wall facing the arriving visitor is covered with wallpaper bearing a brickwork pattern. This fake brick wall evokes an outdoor space: a wall separates a building from the outside, thus establishing a boundary between the contained interior and the nominally public exterior. The red brick connotes factories of the early industrial era, as well as the simplest weapon used in city riots – the brick – or a place to post and spray-paint political messages. Looming over the pristine neoclassical gallery, the wall also alludes to the crudest forms of oppression, such as imprisonment and execution. Sagri has left the narrow end of her wall open, exposing its inner construction and hence the artificiality of the structure. The rear of the wall is plastered and remains white, thus creating a regular gallery space on this side of the wall.

During the exhibition, Sagri – wearing a specially created one-piece costume printed with a picture of her own body dressed in casual clothing – will perform specific movements in front of the wall and around its free corner. These will be divided into four sequences and performed at variable intervals in changing durations. The movement of the performer is organized from left to right along the wall, underlining the sequential, linear, proto-cinematic character of the performance: a build-up of suspense, action, culmination, and finally the repetition of the sequence.

White wall labels sparsely distributed in the galleries are placed at the height normally reserved for labels in a museum and imitate their design. We might imagine strolling through the gallery, looking at paintings or drawings, and then checking the title and date of the work, and the name of the artist. Here, however, the labels refer to things far away from the gallery space. Each label carries a name (of a person or collective body), date and a QR code – a type of barcode that can be read by software available as a free download for most mobile phones. By scanning the code, visitors instantly reach the content stored on the corresponding website. The show thus extends into several other settings and narrations. These range from video works commissioned by Sagri from fellow artists to pieces of music, essays and the websites of specific organizations (such as the artists’ collective CAGE and Embros, the occupied theatre in Athens that has played an important role as a venue for self-organized political and artistic activities in Athens during the recent economic crisis).

In the second gallery, a custom-made machine displays a panorama of a large photograph printed on PVC, continuously scrolling in one direction. The picture was taken in Exarcheia, a district of Athens considered an anarchist home base, on the site where a policeman shot 15-year-old student Alexis Grigoropoulos on the night of December 6, 2008. The riots that followed turned into a general protest against the systemic failure of the state, with its endemic social injustice and escalating poverty. It was the beginning of a confrontation between the government and the people that is still on-going today, and which addresses various concerns, takes different forms and involves a growing number of strategies of self-organization. Sagri’s panorama shows a wall covered with graffiti slogans that can be ascribed to several politically active dissident groups, along with two memorial plaques – one presented by the State and a smaller one installed by Grigoropoulos’s family and friends.

In the third gallery, a small Plexiglas box features a single coin – an American quarter that was placed on a train track and flattened to a thin, oval shape, similar to a guitar pick, with the face of George Washington strangely disfigured, and the words “liberty” and “in God we trust” barely legible. This violent transformation – from money to matter – seems to point to the possibility of larger-scale change and raises the hope that the current order of things is perhaps not as immutable as it appears.

Outside the Kunsthalle, at various locations in Basel, a series of posters presents photographs of the artist physically approaching paintings made in her studio. These photos are annotated with texts that obliquely refer to events that happened in the past, are happening now or will happen in the future.