Klára Hosnedlová

GROWTH

09 Feb - 20 May 2024

Klára Hosnedlová, GROWTH, exhibition view (with performers), Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser / Kunsthalle Basel

Klára Hosnedlová, GROWTH, exhibition view, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser / Kunsthalle Basel

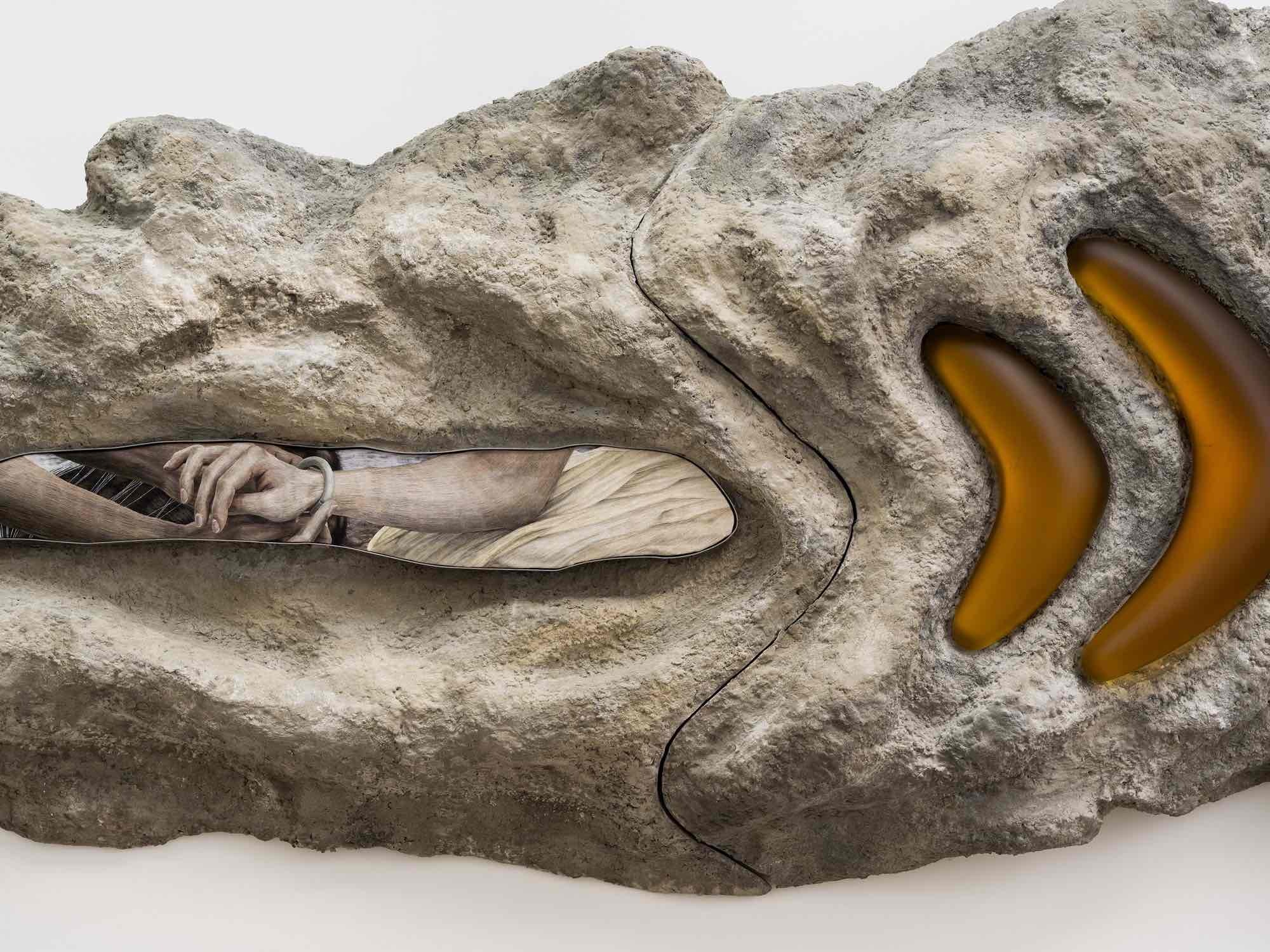

Klára Hosnedlová, Untitled (from the series Growth), 2024, detail, in: Klára Hosnedlová, GROWTH, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser / Kunsthalle Basel

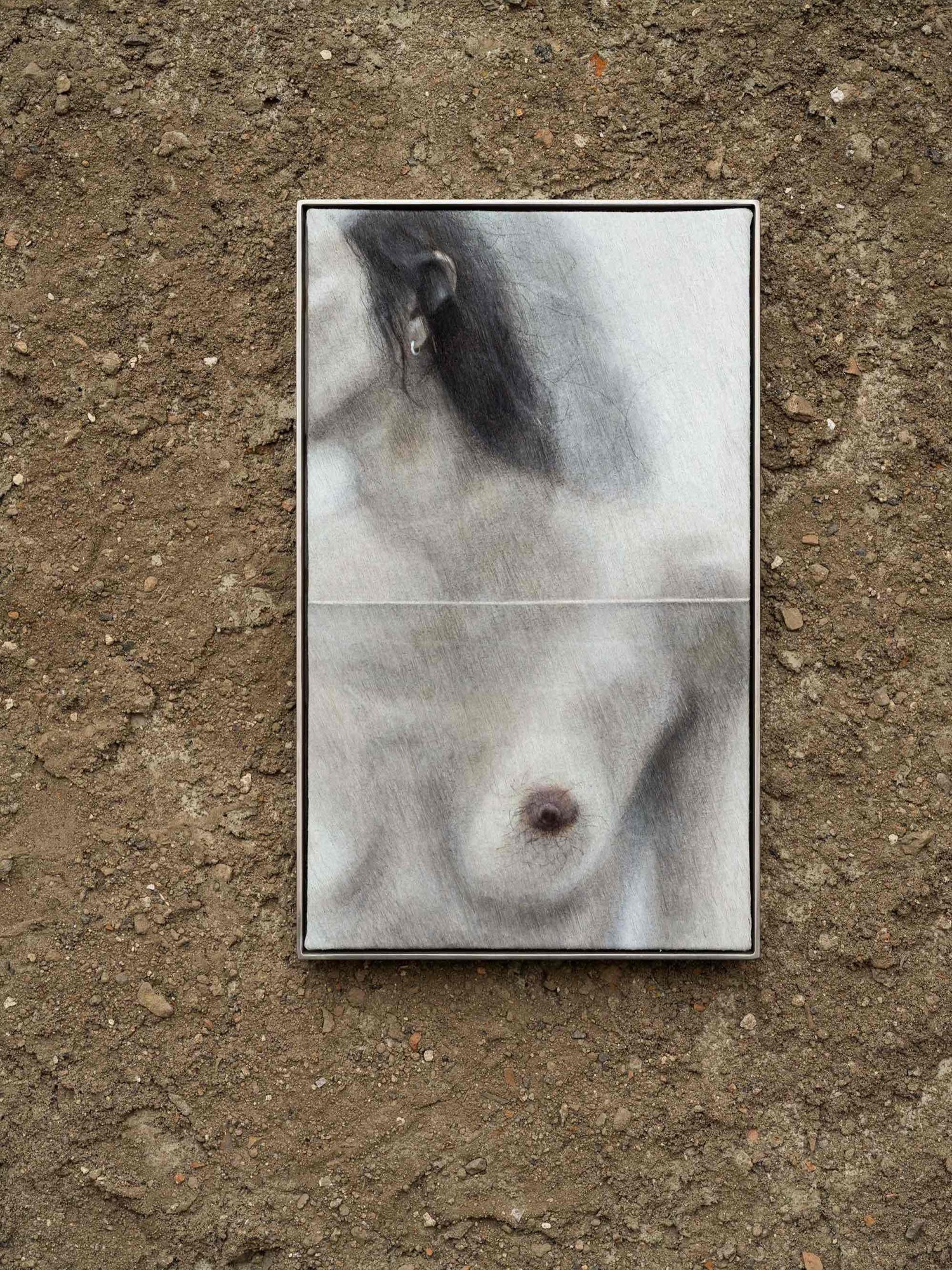

Klára Hosnedlová, Untitled (from the series To Infinity), 2023, installation view, in: Klára Hosnedlová, GROWTH, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser / Kunsthalle Basel

Klára Hosnedlová, GROWTH, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, exhibition view, photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser / Kunsthalle Basel

Klára Hosnedlová, Untitled (from the series Growth), 2024, detail (with performers) , in: Klára Hosnedlová, GROWTH, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser / Kunsthalle Basel

Klára Hosnedlová, Untitled (from the series Growth), 2024, installation view (with performers) , in: Klára Hosnedlová, GROWTH, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser / Kunsthalle Basel

Klára Hosnedlová, GROWTH, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, exhibition view, photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser / Kunsthalle Basel

Klára Hosnedlová, GROWTH, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, exhibition view, photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser / Kunsthalle Basel

Klára Hosnedlová, Untitled (from the series To Infinity), 2023, installation view, in: Klára Hosnedlová, GROWTH, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser / Kunsthalle Basel

Lunar formations, rugged and sandy. The desiccated flesh of dinosaurs, punctuated by glassy ribs, or a beak. Alien cysts trapping frozen, hardened liquid. What bulges from Kunsthalle Basel’s walls in the inaugural room of this solo exhibition, Klára Hosnedlová’s first in Switzerland, could be any of such material formations. Adding to their mystification, each protrusion nestles within it a hyperrealistic figural representation rendered in embroidery. No matter what you recognize in them, these sculptures shrouded in sand with cast glass and needlework are deeply uncanny.

At the center of the room and in some of those that follow, the floor is paved with organized rows of the cement tiles ubiquitous in the public spaces of the former Eastern Bloc that the Czech artist is so familiar with. Hosnedlová has created gaps within their geometric order, pitting them with dirt, puddles of resin, and the occasional dead butterfly or tiny rusty metal element. They seem to be remnants of a bygone nuclear disaster. Or was it an alien invasion? Or the fall of a onceordered, perhaps not entirely human, regime? The evidence suggests something eerie and dystopian.

In this exhibition, as across her oeuvre, Hosnedlová melds sci-fi aesthetics with the meticulously handcrafted, the former indebted to the modernist architecture and historical legacies of Socialist Modernism that she grew up around. She began to experiment with traditional techniques of silk cotton embroidery already while at art school in the class of Czech conceptual artist Jiří Kovanda. The repetitive, painstaking handwork of creating an image from layers of thread fascinated her, with a result that looks so finely detailed as to appear industrially made. The artist revels in such contradictions, and to this day, she sews each embroidery herself in its entirety.

Hosnedlová initially based the motifs for her needlework on found pictures, including stills from postwar Eastern European cinema. Soon thereafter, she began to develop her imagery using a protocol that would define her subsequent practice: she creates non-public performances whose peculiar actions, brutalist backdrops, and retro-futurist costumes she stages and photographs for the exclusive purpose of providing pictorial fodder for the embroideries that will be shown in her next exhibition—where, in turn, she will design the actions, settings, and costumes for her subsequent set of embroideries. And on and on. Thus, each presentation of Hosnedlová’s work over the last years has carried within it the imagery of the performance that preceded it, while each exhibition or presentation also becomes the anticipatory site and backdrop for imagery that she will realize for subsequent, future exhibitions. Science fiction involves, necessarily, some kind of time travel, which the embroidered scenes not only take as inspiration but also enact in their own way.

The embroideries shown at Kunsthalle Basel thus pictorialize different details from photographs of a performance Hosnedlová staged in To Infinity, her preceding show. And, following her protocol, private choreographies enacted within her Kunsthalle Basel show will spur the embroideries for her next. In those on view now, she focuses on fragments of bodies rendered in her typically muted color palette—washes of grays, soft lavenders, flesh tones. They feature close-up depictions of body parts—breasts or shoulders, scalps or hands—sometimes in the act of lighting a fire or handling a technological device or, simply, touching.

In these collections of fragmented bodies, no single person is actually identifiable, and not one body is presented whole. The anonymity of the humanity depicted is such that these appear to be portraits of a species, rather than of individuals. Their portrayal and the societal structures we might intuit from them (as they perform one of humankind’s most essential acts or manipulate a digital screen) leave enigmatic whether they represent a faraway future or the past’s imagination of it. In Hosnedlová’s worlds, eras collide, and “her temporalities are as layered as her formal gestures,” as one critic rightly suggested.

A single framed embroidery appears bathed in dusky light in the second room. A sloping, dirtcovered wall or dike dominates the room and seems to have risen from below the Earth’s crust for the sole purpose of holding up the image. The latter pictures the side of a face and nude torso pressed against a frosted, translucent surface. A similarly milky surface blocks the room that follows, forming a divide and leaving a corridor through which the visitor can pass. To spy through that semi-transparent plastic wall is to notice the earthen piles and diffuse orange light behind it, but scarcely to understand their significance. The only clue, perhaps, is the following: on the plastic sheeting, you can make out blackened smears, traces of cryptic actions created by several performers in the days before the opening of the exhibition. Had they staged a struggle? A ritual? An ecstatic festivity? Nothing is certain. One would have to visit Hosnedlová’s next show and check the embroideries within it to find out.

A coda to the extraordinary cinematic trajectory she has created across the exhibition’s five rooms, the last space is a forest of large-scale suspended sculptures. Imposing, almost monstrous in their organic presence, and inspired by folkloric Bohemian textile traditions, they are comprised of a mixture of linen tow and yarn in gradients of browns and creams. The artist had them manufactured at the Czech Republic’s last extant linen factory, the others in this region with a rich history of textile production having gone bankrupt and closed due to cheaper, more technologically-driven processes outsourced to Asia. Her unruly sculptures were made on the Czech factory’s last still-working machine for processing the natural fiber. Once created, she attached her characteristic embroideries to their shaggy matting, leaving some to hang without this representational adornment.

To spend time within the exhibition is to realize that Hosnedlová doesn’t so much make sculp- ture, embroidery, or installation as build worlds. At once ancestral and post-human, these worlds are inescapably haunting. GROWTH is the young artist’s most expansive exhibition to date, and remarkably, it is only her second institutional solo show ever. Yet, her vision is articulated in an exquisite complexity and already so fully formed. By combining her interests in history, craft, fashion, design, architecture, sculpture, and performance, Hosnedlová has not only metamor- phosed Kunsthalle Basel into an ominous, highly theatrical, totally immersive environment but instigated a questioning of both our industrial past and our increasingly technologized future.

By the time you get to the last room of the exhi- bition, you understand that its title, GROWTH, may play on seemingly positive phenomena— the caterpillar that becomes a butterfly, a child who becomes an adult, as well as the growth of wealth, technology, and so-called global interconnectedness, and, with these, perceived access and ease. Yet, to speak of (a) growth can also signal a potentially threatening and sometimes unstoppable corporeal enlargement—a cancer- ous tumor or cyst. The ambiguity cuts to the core of the exhibition and to Hosnedlová’s oeuvre as a whole. Did the generations that came before us aspire to growth at any cost, she appears to ask? What do we do with what was lost or gained in the process? And do we still even desire the incessant and frictionless growth that has been considered synonymous with progress? If so, the urgent question remains: What responsibility do we have to our own still-unknown future and the people who will inhabit it?

Curator: Elena Filipovic

At the center of the room and in some of those that follow, the floor is paved with organized rows of the cement tiles ubiquitous in the public spaces of the former Eastern Bloc that the Czech artist is so familiar with. Hosnedlová has created gaps within their geometric order, pitting them with dirt, puddles of resin, and the occasional dead butterfly or tiny rusty metal element. They seem to be remnants of a bygone nuclear disaster. Or was it an alien invasion? Or the fall of a onceordered, perhaps not entirely human, regime? The evidence suggests something eerie and dystopian.

In this exhibition, as across her oeuvre, Hosnedlová melds sci-fi aesthetics with the meticulously handcrafted, the former indebted to the modernist architecture and historical legacies of Socialist Modernism that she grew up around. She began to experiment with traditional techniques of silk cotton embroidery already while at art school in the class of Czech conceptual artist Jiří Kovanda. The repetitive, painstaking handwork of creating an image from layers of thread fascinated her, with a result that looks so finely detailed as to appear industrially made. The artist revels in such contradictions, and to this day, she sews each embroidery herself in its entirety.

Hosnedlová initially based the motifs for her needlework on found pictures, including stills from postwar Eastern European cinema. Soon thereafter, she began to develop her imagery using a protocol that would define her subsequent practice: she creates non-public performances whose peculiar actions, brutalist backdrops, and retro-futurist costumes she stages and photographs for the exclusive purpose of providing pictorial fodder for the embroideries that will be shown in her next exhibition—where, in turn, she will design the actions, settings, and costumes for her subsequent set of embroideries. And on and on. Thus, each presentation of Hosnedlová’s work over the last years has carried within it the imagery of the performance that preceded it, while each exhibition or presentation also becomes the anticipatory site and backdrop for imagery that she will realize for subsequent, future exhibitions. Science fiction involves, necessarily, some kind of time travel, which the embroidered scenes not only take as inspiration but also enact in their own way.

The embroideries shown at Kunsthalle Basel thus pictorialize different details from photographs of a performance Hosnedlová staged in To Infinity, her preceding show. And, following her protocol, private choreographies enacted within her Kunsthalle Basel show will spur the embroideries for her next. In those on view now, she focuses on fragments of bodies rendered in her typically muted color palette—washes of grays, soft lavenders, flesh tones. They feature close-up depictions of body parts—breasts or shoulders, scalps or hands—sometimes in the act of lighting a fire or handling a technological device or, simply, touching.

In these collections of fragmented bodies, no single person is actually identifiable, and not one body is presented whole. The anonymity of the humanity depicted is such that these appear to be portraits of a species, rather than of individuals. Their portrayal and the societal structures we might intuit from them (as they perform one of humankind’s most essential acts or manipulate a digital screen) leave enigmatic whether they represent a faraway future or the past’s imagination of it. In Hosnedlová’s worlds, eras collide, and “her temporalities are as layered as her formal gestures,” as one critic rightly suggested.

A single framed embroidery appears bathed in dusky light in the second room. A sloping, dirtcovered wall or dike dominates the room and seems to have risen from below the Earth’s crust for the sole purpose of holding up the image. The latter pictures the side of a face and nude torso pressed against a frosted, translucent surface. A similarly milky surface blocks the room that follows, forming a divide and leaving a corridor through which the visitor can pass. To spy through that semi-transparent plastic wall is to notice the earthen piles and diffuse orange light behind it, but scarcely to understand their significance. The only clue, perhaps, is the following: on the plastic sheeting, you can make out blackened smears, traces of cryptic actions created by several performers in the days before the opening of the exhibition. Had they staged a struggle? A ritual? An ecstatic festivity? Nothing is certain. One would have to visit Hosnedlová’s next show and check the embroideries within it to find out.

A coda to the extraordinary cinematic trajectory she has created across the exhibition’s five rooms, the last space is a forest of large-scale suspended sculptures. Imposing, almost monstrous in their organic presence, and inspired by folkloric Bohemian textile traditions, they are comprised of a mixture of linen tow and yarn in gradients of browns and creams. The artist had them manufactured at the Czech Republic’s last extant linen factory, the others in this region with a rich history of textile production having gone bankrupt and closed due to cheaper, more technologically-driven processes outsourced to Asia. Her unruly sculptures were made on the Czech factory’s last still-working machine for processing the natural fiber. Once created, she attached her characteristic embroideries to their shaggy matting, leaving some to hang without this representational adornment.

To spend time within the exhibition is to realize that Hosnedlová doesn’t so much make sculp- ture, embroidery, or installation as build worlds. At once ancestral and post-human, these worlds are inescapably haunting. GROWTH is the young artist’s most expansive exhibition to date, and remarkably, it is only her second institutional solo show ever. Yet, her vision is articulated in an exquisite complexity and already so fully formed. By combining her interests in history, craft, fashion, design, architecture, sculpture, and performance, Hosnedlová has not only metamor- phosed Kunsthalle Basel into an ominous, highly theatrical, totally immersive environment but instigated a questioning of both our industrial past and our increasingly technologized future.

By the time you get to the last room of the exhi- bition, you understand that its title, GROWTH, may play on seemingly positive phenomena— the caterpillar that becomes a butterfly, a child who becomes an adult, as well as the growth of wealth, technology, and so-called global interconnectedness, and, with these, perceived access and ease. Yet, to speak of (a) growth can also signal a potentially threatening and sometimes unstoppable corporeal enlargement—a cancer- ous tumor or cyst. The ambiguity cuts to the core of the exhibition and to Hosnedlová’s oeuvre as a whole. Did the generations that came before us aspire to growth at any cost, she appears to ask? What do we do with what was lost or gained in the process? And do we still even desire the incessant and frictionless growth that has been considered synonymous with progress? If so, the urgent question remains: What responsibility do we have to our own still-unknown future and the people who will inhabit it?

Curator: Elena Filipovic