Toyin Ojih Odutola

Ilé Oriaku

07 Jun - 01 Sep 2024

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Ilé Oriaku, exhibition view, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Ilé Oriaku, exhibition view, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Ilé Oriaku, exhibition view, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Ilé Oriaku, exhibition view, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Toyin Ojih Odutola, detail view, in: Toyin Ojih Odutola, Ilé Oriaku, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Ilé Oriaku, exhibition view, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Don’t Be Afraid; Use What I Gave You, 2023, installation view, in: Toyin Ojih Odutola, Ilé Oriaku, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Toyin Ojih Odutola, When Past Meets Future, Will They Speak the Same Language? (Who Are You? / Mother?), 2023, installation view, in: Toyin Ojih Odutola, Ilé Oriaku, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Ilé Oriaku, exhibition view, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Ilé Oriaku, exhibition view, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

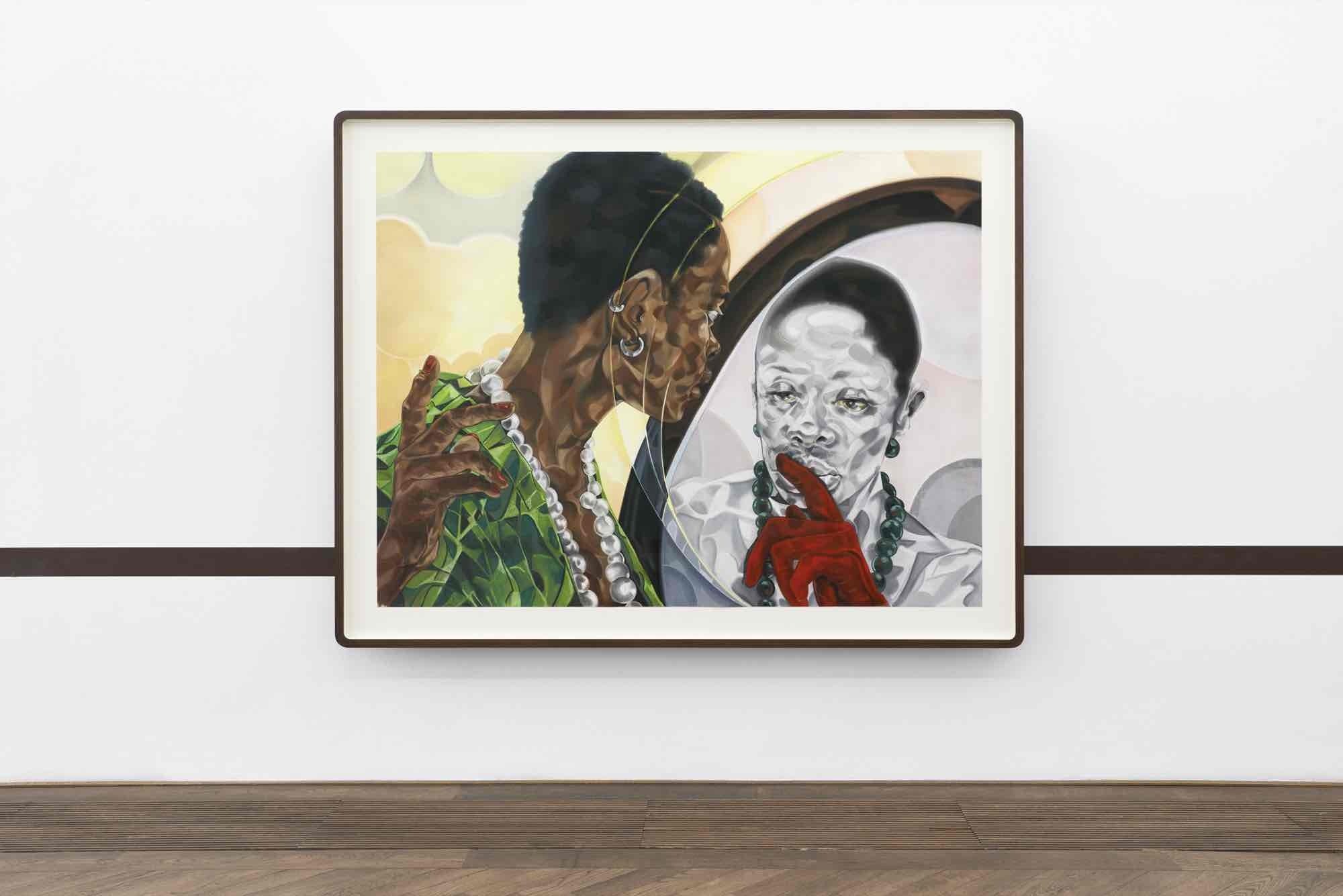

Upon entering the exhibition, we find ourselves immersed in a space populated by a diverse array of unique characters. Some figures are partially obscured while others meet our gaze directly, their forms shifting through windows and reflective surfaces. They change attire, apply makeup, gaze into mirrors, converse with others, rather simply rest in contemplation, preparing to move, maybe to dance. Whether alone or in groups, each moment seems to be charged with significance. Dressed in costume-like clothing, they wear striking red gloves, transparent veils, elaborate skirts and shoes. Their vibrant outfits and bare skin contrast sharply with the colorful and blurry backgrounds, and seamlessly blend into the set design. As one moves through the exhibition, the rhythm of the life of some spiritual performers becomes apparent, turning the viewer into an onlooker witnessing their moments of preparation and introspection inside the troupe’s house. Ilé Oriaku (House of Abundance) weaves these scenes into a tapestry of narration, transformation, ritual, and bold artistic expression.

In Toyin Ojih Odutola’s first solo exhibition in Switzerland, she showcases a new body of work at Kunsthalle Basel, consisting of twenty-seven drawings depicting episodic scenes within the exhibitionʼs overarching narrative, which revolves around the themes of language and grief. For her monumental and detailed works, Ojih Odutola uses various materials, from charcoal, chalk, and pastel on paper, linen, or canvas board, to colored pencil and graphite on Dura-Lar film. Engaging with a grand tradition of portrait painting through a practice that channels the artistry of drawing, her work captures the fine qualities of her characters.

Visitors are welcomed in a space that evokes an imaginary Mbari house—a sacred space rooted in the traditions of the Nigerian Igbo community made to honor the goddess Ala, amongst other deities, who protect the Owerri Igbo tribe from supernatural calamities and misfortunes. Traditionally crafted from raw materials—clay, wood, and straw— these structures were adorned with figures, sculptures, geometric patterns, and wall paintings depicting spiritual or mythological themes. A grid on the wall connects the series of drawings throughout the entire exhibition space. The pattern is reminiscent of the scaffolding of Ojih Odutola’s imagined Mbari house, Ilé Oriaku. This name pays tribute to her grandmother and uncle, who belong to the Nigerian Igbo and Yoruba ethnic groups. “Ilé” means “house,” “building,” or “home” in Yoruba, while “Oriaku” is her grandmother’s Igbo name.

Through meticulous attention to detail, shifts in perspective, and physical proximity, Ojih Odutola establishes a close connection between the viewer and the figures. Through subtle facial expressions, gestures, and surroundings, the drawing creates an intimate atmosphere and encourages viewers to contemplate both with and through a beholder. Flashes of everyday life and routines in Ojih Odutolaʼs art enhance the viewer’s connection to them. These scenes convey the essence of daily transformation and closeness, while the choice of colors, inspired by traditional Mbari art, adds layers of cultural significance. Yellow, symbolizing vitality, is sourced from a sacred site along Nigeria’s Imo River, whereas green,representing renewal, comes from the river’s clay. The imported European washing blue offers contrast, while red, derived from camwood, signifies passion. At the same time, though, these colors are not mere historical and cultural references, they are firmly rooted in the present where the portrayed figures are accessible and approachable, exuding a contemporaneity that bridges different timelines and cultural contexts.

Each architectural space of the exhibition is designed as a distinct scene that captures varied moments over the course of a grieving process. Ojih Odutola, a storyteller at heart, uses drawing as her medium to craft counter narratives. Challenging established histories, her stories investigate the potential of a visual language to generate new meanings and interpretations. Much like an author, she immerses herself in her subject matter, conducting research and developing her characters over extended periods to create comprehensive and deeply-intimate narratives. Each story unfolds in a series of works presented in a chapter-like structure. It is no coincidence that with Ojih Odutola the drawing pen resembles a writerʼs.

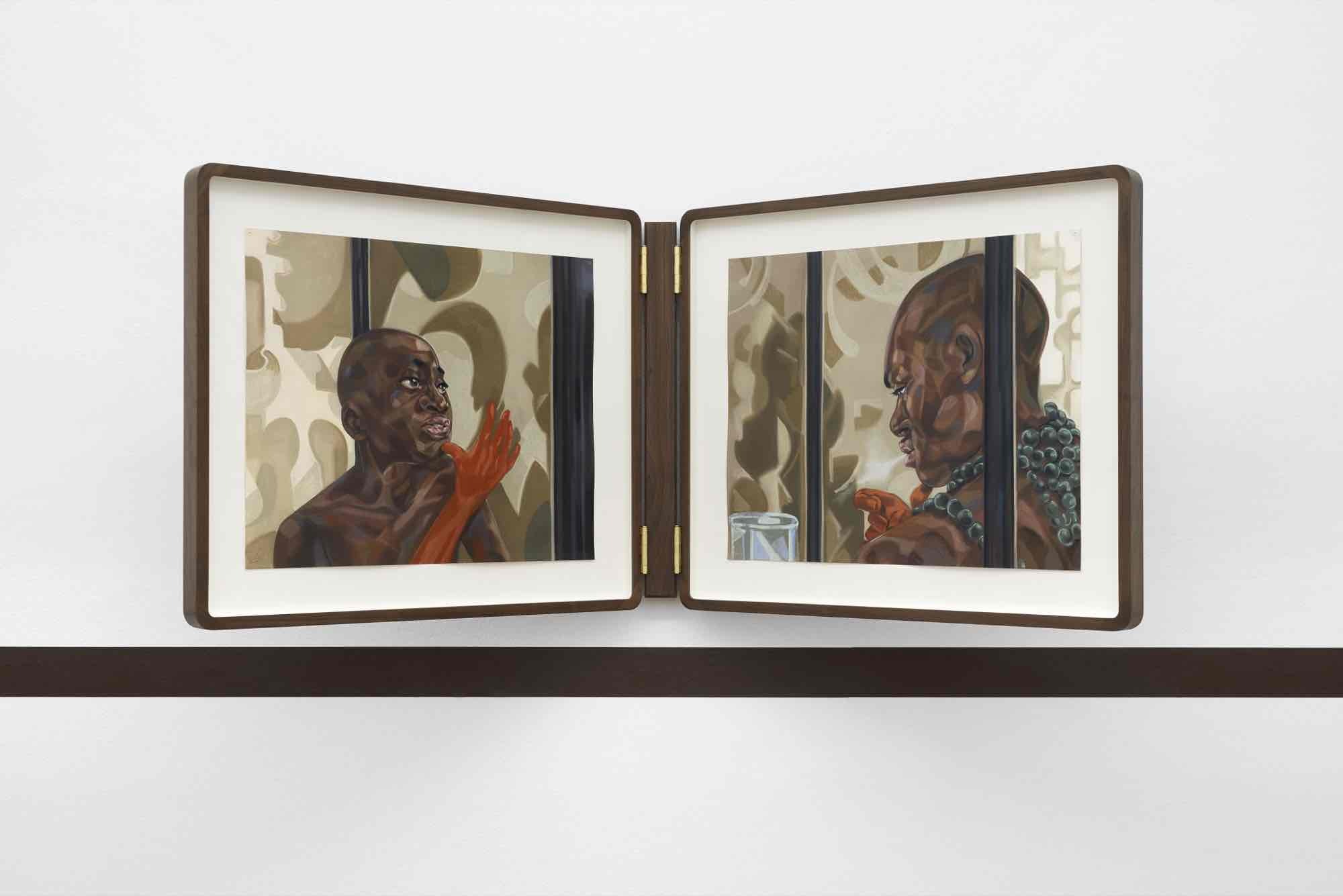

Although her drawings are rooted in texts, they instinctively transcend words and create a visual language with cues that language cannot convey. The diptychs What To Ask When You Meet Your Future Self?, 2022–23, and When Past Meets Future, Will They Speak the Same Language? (Who Are You? / Mother?), 2023, show two individuals at different ages and presumably in the same place. Not only through expressive facial expressions, but also through American Sign Language, the characters communicate with each other, bridging time and identity. Despite their visual separation, the protagonists remain connected through their interactions, inviting viewers to cotemplate the relationship between past and future selves within a unified space.

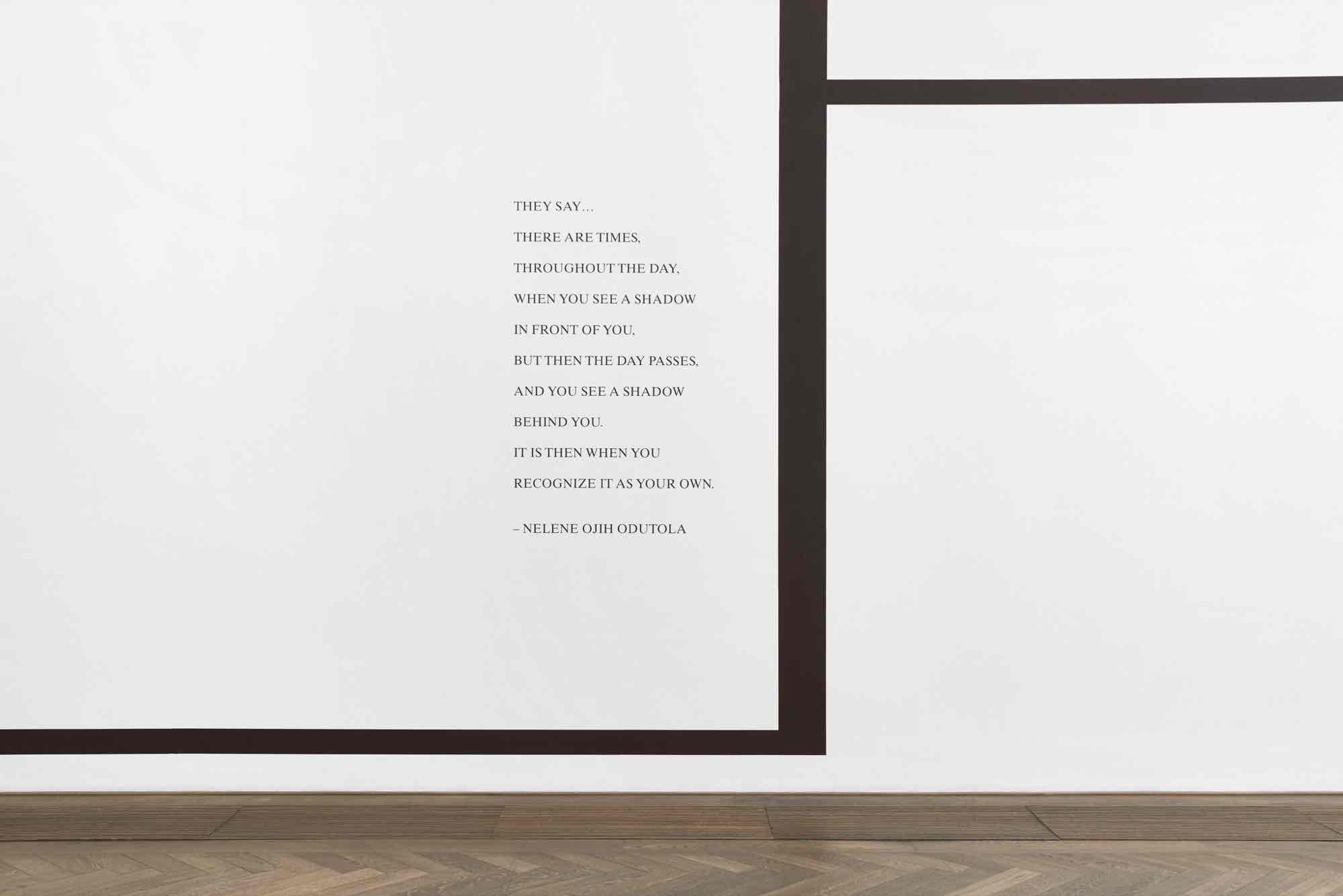

Language appears not only through her drawings but also through the voices of her family. In the first room, visitors are introduced to a poem written by her mother, Nelene. This initial encounter sets the tone for the profoundly personal narrative that unfolds throughout the exhibition. Later, one can listen to the sound piece that combines an audio conversation with her grandmother and bird songs from her teenage home in Alabama. In Ilé Oriaku / Nature Girl, 2024, her grandmother detailes her Igbo name: “I am here to enjoy.” Ojih Odutola’s family history and the way it is conveyed in the exhibition sharply illustrates how colonial forces irreversibly interfere and thereby transform the various facets of a community’s cultural composition. However, she reflects on instances where she engages in dialogue with her relatives in Nigeria, overcoming linguistic barriers imposed by external disruptions to find mutual understanding. Her work demonstrates that when words seem insufficient, new forms of communication—whether through art, sound, motions, or shared silence—come to the fore, allowing for a deeper, more visceral confluence.

While the exhibition’s visual narrative circles around the theme of loss, the moment of personal grief sets the stage for a broader exploration of ways of mourning and communication. Ojih Odutola’s drawings serve as a testament to the idea that language can be both a bridge and a barrier. Titles like She’s a Good Boy (Study), 2022, and Third Person Singular (kẹta eniyan / dị ndụ atọ) or Must She Account for Everything?, both 2023, suggest an interaction between the depicted figures or imply that an external presence is encouraging them with words of reassurance. By referencing various languages and narrative perspectives, the titles illustrate how contrasts between image and language can nevertheless lead to moments of convergence weaving written words into the visual language of the drawings.

In Toyin Ojih Odutola’s first solo exhibition in Switzerland, she showcases a new body of work at Kunsthalle Basel, consisting of twenty-seven drawings depicting episodic scenes within the exhibitionʼs overarching narrative, which revolves around the themes of language and grief. For her monumental and detailed works, Ojih Odutola uses various materials, from charcoal, chalk, and pastel on paper, linen, or canvas board, to colored pencil and graphite on Dura-Lar film. Engaging with a grand tradition of portrait painting through a practice that channels the artistry of drawing, her work captures the fine qualities of her characters.

Visitors are welcomed in a space that evokes an imaginary Mbari house—a sacred space rooted in the traditions of the Nigerian Igbo community made to honor the goddess Ala, amongst other deities, who protect the Owerri Igbo tribe from supernatural calamities and misfortunes. Traditionally crafted from raw materials—clay, wood, and straw— these structures were adorned with figures, sculptures, geometric patterns, and wall paintings depicting spiritual or mythological themes. A grid on the wall connects the series of drawings throughout the entire exhibition space. The pattern is reminiscent of the scaffolding of Ojih Odutola’s imagined Mbari house, Ilé Oriaku. This name pays tribute to her grandmother and uncle, who belong to the Nigerian Igbo and Yoruba ethnic groups. “Ilé” means “house,” “building,” or “home” in Yoruba, while “Oriaku” is her grandmother’s Igbo name.

Through meticulous attention to detail, shifts in perspective, and physical proximity, Ojih Odutola establishes a close connection between the viewer and the figures. Through subtle facial expressions, gestures, and surroundings, the drawing creates an intimate atmosphere and encourages viewers to contemplate both with and through a beholder. Flashes of everyday life and routines in Ojih Odutolaʼs art enhance the viewer’s connection to them. These scenes convey the essence of daily transformation and closeness, while the choice of colors, inspired by traditional Mbari art, adds layers of cultural significance. Yellow, symbolizing vitality, is sourced from a sacred site along Nigeria’s Imo River, whereas green,representing renewal, comes from the river’s clay. The imported European washing blue offers contrast, while red, derived from camwood, signifies passion. At the same time, though, these colors are not mere historical and cultural references, they are firmly rooted in the present where the portrayed figures are accessible and approachable, exuding a contemporaneity that bridges different timelines and cultural contexts.

Each architectural space of the exhibition is designed as a distinct scene that captures varied moments over the course of a grieving process. Ojih Odutola, a storyteller at heart, uses drawing as her medium to craft counter narratives. Challenging established histories, her stories investigate the potential of a visual language to generate new meanings and interpretations. Much like an author, she immerses herself in her subject matter, conducting research and developing her characters over extended periods to create comprehensive and deeply-intimate narratives. Each story unfolds in a series of works presented in a chapter-like structure. It is no coincidence that with Ojih Odutola the drawing pen resembles a writerʼs.

Although her drawings are rooted in texts, they instinctively transcend words and create a visual language with cues that language cannot convey. The diptychs What To Ask When You Meet Your Future Self?, 2022–23, and When Past Meets Future, Will They Speak the Same Language? (Who Are You? / Mother?), 2023, show two individuals at different ages and presumably in the same place. Not only through expressive facial expressions, but also through American Sign Language, the characters communicate with each other, bridging time and identity. Despite their visual separation, the protagonists remain connected through their interactions, inviting viewers to cotemplate the relationship between past and future selves within a unified space.

Language appears not only through her drawings but also through the voices of her family. In the first room, visitors are introduced to a poem written by her mother, Nelene. This initial encounter sets the tone for the profoundly personal narrative that unfolds throughout the exhibition. Later, one can listen to the sound piece that combines an audio conversation with her grandmother and bird songs from her teenage home in Alabama. In Ilé Oriaku / Nature Girl, 2024, her grandmother detailes her Igbo name: “I am here to enjoy.” Ojih Odutola’s family history and the way it is conveyed in the exhibition sharply illustrates how colonial forces irreversibly interfere and thereby transform the various facets of a community’s cultural composition. However, she reflects on instances where she engages in dialogue with her relatives in Nigeria, overcoming linguistic barriers imposed by external disruptions to find mutual understanding. Her work demonstrates that when words seem insufficient, new forms of communication—whether through art, sound, motions, or shared silence—come to the fore, allowing for a deeper, more visceral confluence.

While the exhibition’s visual narrative circles around the theme of loss, the moment of personal grief sets the stage for a broader exploration of ways of mourning and communication. Ojih Odutola’s drawings serve as a testament to the idea that language can be both a bridge and a barrier. Titles like She’s a Good Boy (Study), 2022, and Third Person Singular (kẹta eniyan / dị ndụ atọ) or Must She Account for Everything?, both 2023, suggest an interaction between the depicted figures or imply that an external presence is encouraging them with words of reassurance. By referencing various languages and narrative perspectives, the titles illustrate how contrasts between image and language can nevertheless lead to moments of convergence weaving written words into the visual language of the drawings.