Independence

22 Sep - 02 Dec 2018

INDEPENDENCE

22 September – 2 December 2018

Under the term “autonomy”, independence in art long meant freedom of artistic creation independent of market or government influences. Especially in the second half of the twentieth century, artists served as a projection surface for a life freed from constraints that promised relative independence from socioeconomic conditions. Yet this unrealistic idea of artists having the freedom you, as a civic subject, do not dare to take has meanwhile been largely abandoned. A number of artists even pursued a critique of the institutions that include them and of the constraints associated with those institutions, though in the long run this didn’t lead anywhere. As necessary as it was, the constant pointing to the unfreedom of one’s situation eventually did start to smack of paid criticism and, instead of transforming the situation identified through analysis and critique, stabilised the institutions which accepted the criticism as a distinction. Nowadays, the situation is porous and the individual actors are more interdependent than ever. And yet the art world is at the same time a self-contained world whose rules and openings call for constant questioning.

The artistic practice presented in Independence is not a sceptical, detached position, but rather one that draws on unlimited resources inside the structures and stories of art. It is downright fascinated with mechanisms that shape the processes of value creation and taste formation. It is interested in how and when symbolic added value and desire are created. Especially in contemporary art, the latter manifest themselves as forms of a refined exploration of aesthetic and social dynamics – dynamics which occur in what tend to be more well-defined systems in other spheres also invoked here, such as fashion and film.

Both inside and outside of the Kunsthalle building, Independence is framed by backdrops that reference two films: Milos Forman’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), in which Jack Nicholson questions the prevailing order in a mental institution and turns it upside down. This film “has no interest in being about insanity. It is about a free spirit in a closed system” (Roger Ebert, film critic). The second film being referenced is Melancholia by Lars van Trier (2011). In this film, Justine (Kirsten Dunst), who is suffering from depression, foresees the collision of earth with the planet “Melancholia”. The confrontation with a sense of existential emptiness is central to this apocalyptic film. The cinematic references open up interpretations that could be applied allegorically to the institution of art and its society – an institution by itself in whose relentless dynamic some individuals find themselves brought to the edge of a psychological abyss.

The personal living environment provides a potential place of retreat. One of the characteristics of the artistic approach underlying Independence is that it lets the personal living environment and lifestyle, the “friends, lovers and financiers” of artistic practice, come very close – so close, in fact, that a cycle of production and recycling is created where it becomes fuzzy who acts and appropriates on whose behalf. And what is more, artistic production ends up becoming really staged and performed as a result of the specific social background – another backdrop of the exhibition – which no longer distinguishes between what is private and what is not.

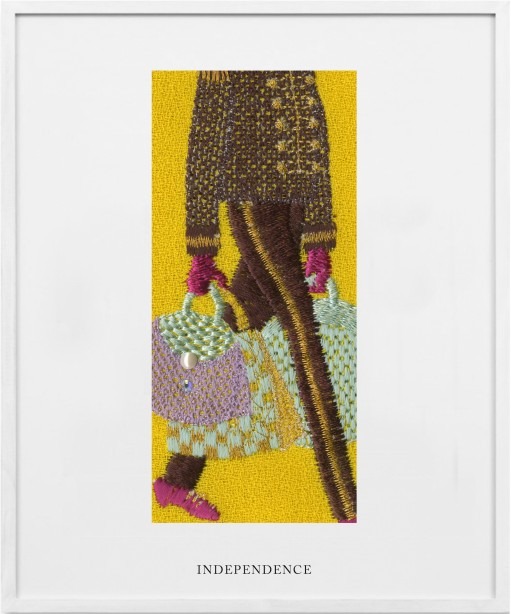

Arranged within these backdrops are new and older works, including many stemming from groups of works. for example, Independence features a series of new paintings which draw on imagery of the Japan collection of a famous St. Gallen-based textile company. From the 1960s until recently, the company developed figurative imagery for its Japanese clients, which represented a “typically European haute bourgeoisie” taste for luxury – imagery serving a demand in showing a variety of embroidered scenes in styles ranging from Art Deco to Dior’s New Look. These and other works exemplifying the practice demonstrate an interest in cultural transfer processes of styles and fashions within a sphere or beyond it, tracing global trajectories. The mechanisms of fashion, its dazzling power of seduction, of creating a desire to be someone else, and the possibilities it offers to embody or simulate identities are one of the key frames of reference for the practice presented here. It often operates similar to fashion whose logic ranges between the market and an elusive irrationality.

Another protagonist of Independence is Aibo. This silver-coloured robot dog is currently only available on the Japanese market through a lottery, a form of artificial scarcity that creates extreme desire. Hence it is celebrating its European premiere at the Kunsthalle Bern. The word “aibo” is Japanese for “partner” and is an acronym for “Artificial Intelligence Robot”. Aibo is no longer a toy like its first version in the late 1990s but a teachable artificial intelligence for the contemporary Japanese household. Some “events” in Independence and in this artistic practice in general also infiltrate (marketing) strategies of recent and older art history from other spheres. Practices of historical conceptual art or of “relational aesthetics”, which pushed social interactions between the public and the artist with feel-good actions, are discreetly taken up.

Against this backdrop of numerous references, the question remains what kind of independence is being declared here. Is it the independence from the Kunsthalle which shows one’s work? From the market? And if so, from which one? Or in general from the constraints of being in the world and from regulative structures that may be socially shared? The flipside of independence is and continues to be the lack of dissemination which eludes access, while at the same time being open to all invocations. It, too, finds a backdrop here.

The artist presented in this exhibition remains nameless, for now. Visitors may wonder whether it is worth travelling to the opening when it remains unclear who is hiding behind the invitation to the exhibition. To the artist, on the other hand, it may offer the freedom to place special emphasis on the exhibition itself rather than on the marketing of the name.

While the name may represent a promise or create certain expectations, self-imposed anonymity flirts with seduction through the appeal of the mysterious.

22 September – 2 December 2018

Under the term “autonomy”, independence in art long meant freedom of artistic creation independent of market or government influences. Especially in the second half of the twentieth century, artists served as a projection surface for a life freed from constraints that promised relative independence from socioeconomic conditions. Yet this unrealistic idea of artists having the freedom you, as a civic subject, do not dare to take has meanwhile been largely abandoned. A number of artists even pursued a critique of the institutions that include them and of the constraints associated with those institutions, though in the long run this didn’t lead anywhere. As necessary as it was, the constant pointing to the unfreedom of one’s situation eventually did start to smack of paid criticism and, instead of transforming the situation identified through analysis and critique, stabilised the institutions which accepted the criticism as a distinction. Nowadays, the situation is porous and the individual actors are more interdependent than ever. And yet the art world is at the same time a self-contained world whose rules and openings call for constant questioning.

The artistic practice presented in Independence is not a sceptical, detached position, but rather one that draws on unlimited resources inside the structures and stories of art. It is downright fascinated with mechanisms that shape the processes of value creation and taste formation. It is interested in how and when symbolic added value and desire are created. Especially in contemporary art, the latter manifest themselves as forms of a refined exploration of aesthetic and social dynamics – dynamics which occur in what tend to be more well-defined systems in other spheres also invoked here, such as fashion and film.

Both inside and outside of the Kunsthalle building, Independence is framed by backdrops that reference two films: Milos Forman’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), in which Jack Nicholson questions the prevailing order in a mental institution and turns it upside down. This film “has no interest in being about insanity. It is about a free spirit in a closed system” (Roger Ebert, film critic). The second film being referenced is Melancholia by Lars van Trier (2011). In this film, Justine (Kirsten Dunst), who is suffering from depression, foresees the collision of earth with the planet “Melancholia”. The confrontation with a sense of existential emptiness is central to this apocalyptic film. The cinematic references open up interpretations that could be applied allegorically to the institution of art and its society – an institution by itself in whose relentless dynamic some individuals find themselves brought to the edge of a psychological abyss.

The personal living environment provides a potential place of retreat. One of the characteristics of the artistic approach underlying Independence is that it lets the personal living environment and lifestyle, the “friends, lovers and financiers” of artistic practice, come very close – so close, in fact, that a cycle of production and recycling is created where it becomes fuzzy who acts and appropriates on whose behalf. And what is more, artistic production ends up becoming really staged and performed as a result of the specific social background – another backdrop of the exhibition – which no longer distinguishes between what is private and what is not.

Arranged within these backdrops are new and older works, including many stemming from groups of works. for example, Independence features a series of new paintings which draw on imagery of the Japan collection of a famous St. Gallen-based textile company. From the 1960s until recently, the company developed figurative imagery for its Japanese clients, which represented a “typically European haute bourgeoisie” taste for luxury – imagery serving a demand in showing a variety of embroidered scenes in styles ranging from Art Deco to Dior’s New Look. These and other works exemplifying the practice demonstrate an interest in cultural transfer processes of styles and fashions within a sphere or beyond it, tracing global trajectories. The mechanisms of fashion, its dazzling power of seduction, of creating a desire to be someone else, and the possibilities it offers to embody or simulate identities are one of the key frames of reference for the practice presented here. It often operates similar to fashion whose logic ranges between the market and an elusive irrationality.

Another protagonist of Independence is Aibo. This silver-coloured robot dog is currently only available on the Japanese market through a lottery, a form of artificial scarcity that creates extreme desire. Hence it is celebrating its European premiere at the Kunsthalle Bern. The word “aibo” is Japanese for “partner” and is an acronym for “Artificial Intelligence Robot”. Aibo is no longer a toy like its first version in the late 1990s but a teachable artificial intelligence for the contemporary Japanese household. Some “events” in Independence and in this artistic practice in general also infiltrate (marketing) strategies of recent and older art history from other spheres. Practices of historical conceptual art or of “relational aesthetics”, which pushed social interactions between the public and the artist with feel-good actions, are discreetly taken up.

Against this backdrop of numerous references, the question remains what kind of independence is being declared here. Is it the independence from the Kunsthalle which shows one’s work? From the market? And if so, from which one? Or in general from the constraints of being in the world and from regulative structures that may be socially shared? The flipside of independence is and continues to be the lack of dissemination which eludes access, while at the same time being open to all invocations. It, too, finds a backdrop here.

The artist presented in this exhibition remains nameless, for now. Visitors may wonder whether it is worth travelling to the opening when it remains unclear who is hiding behind the invitation to the exhibition. To the artist, on the other hand, it may offer the freedom to place special emphasis on the exhibition itself rather than on the marketing of the name.

While the name may represent a promise or create certain expectations, self-imposed anonymity flirts with seduction through the appeal of the mysterious.