The Idea of Africa (re-invented) #2

15 Feb - 27 Mar 2011

THE IDEA OF AFRICA (RE-INVENTED) #2

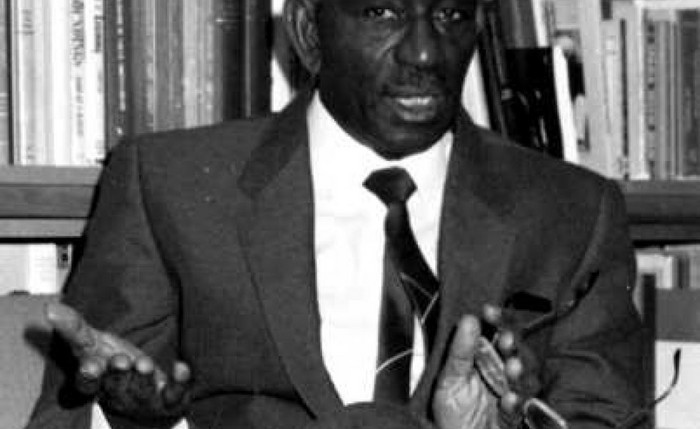

CHEIKH ANTA DIOP

05.02. - 27.03.2011

This second exhibition in the project The idea of Africa (re-invented) is smaller in scale, less visual, more discursive, and indirectly tackles one of the most sensitive subjects: race. An anecdote has been lingering in my head since visiting Documenta XI in 2002, and maybe indirectly functioned as the impetus for this project. Strolling through the exhibition in Kassel, an acquaintance and colleague of mine could not withhold his irritation by his perception of the ubiquitous black body in the exhibition. It seemed as if in a strange way he considered a white body as neutral and normative in the context of an international exhibition. Or maybe his irritation arose because the black bodies in question were not contained in an exotic framework? I don’t know, but due to this fait-divers I was prompted to read a potentially involuntary subtext within Documenta XI, in the end an important element in the perception and the experience of an exhibition. Even if unintended, the exhibition provided an important shift of the gravity centre in the apparently still contested domain of skin colour in contemporary society, and it shed a clearer light on the preconceived assumptions under which a large scale exhibition like Documenta operates. Though the global orientation of Documenta XI focussed on how contemporary art in all its different forms can continue to develop in a dialectic relationship to the entirety of global culture, taking into account the current political, technological and ideological conflicts, developments and mixtures, it proved an extremely "difficult and sensitive" undertaking indeed. Decisive in the end was the breaking of taboos associated with the exhibition. The artistic director Okwui Enwezor cast doubt on Western culture’s claim to primacy by shifting, even inverting, the centres of development and the references to them.

The Idea of Africa (re-invented) is, as explained in the newspaper accompanying the first edition, inspired by the titles of two books by the Congolese philosopher Valentin Yves Mudimbe. Both trace how a certain “idea” of Africa was invented and constructed by the Western world from the Ancient Greeks until the 20th Century. Mudimbe also examines how African scholars who have worked within the limits of imposed language and epistemological frames ‘wrote back’. The exhibition-project at hand focuses on artistic and intellectual endeavours that trace another history, in which the ‘idea’ of Africa is not already a ‘given’ framed by the West.

Enter Senegalese historian, anthropologist, physicist and politician Cheikh Anta Diop (29 December 1923 in Thieytou, Diourbel Region - 7 February 1986 in Dakar). For Valentin Yves Mudimbe, Diop’s work on the cultural experiences of Africa is part of the most extreme examples of an ideological process set in motion by a group of African scholars in the 1950s: they made a distinction between “good” and “bad” works about Africa, according to their conception of the value of their own civilisation.[1] Diop’s ideas were formed early in his career and changed little thereafter. In lectures and articles in the early 1950s, he already proposed his main theses. Diop’s most controversial theory is of course that the Ancient Egyptians were Black Africans. By consequence, Western civilization, claiming to source itself in Ancient Greece – which was highly influenced by Egypt – would owe an enormous debt to a black civilization, an idea exorcised and shunned by the West from the 18th Century onwards.[2] The question of the race of ancient Egyptians was raised historically as a product of the scientific racism[3] of the 18th and 19th centuries. Since the second half of the 20th century, scholarly consensus has held that applying modern notions of race to ancient Egypt is anachronistic, but the debate has been revived in the popular domain of Afrocentric historiography and Black nationalism which tends to insist that Ancient Egypt was a "black civilization", with particular focus on the race of specific notable individuals from Dynastic times, including Tutankhamun, Cleopatra VII, and also the model for the Great Sphinx of Giza. For Diop this black Egyptian civilisation not only originated most important aspects of human social and intellectual development, but was also distinct from Eurasian societies in its matriarchal, spiritual, peaceable and humanistic character. Given that ancient Greece – and hence all European civilisation – was heavily influenced by this allegedly African Egyptian culture, Africa, Diop urged, must recover the glories of its ancient past, rejecting the colonial and racist mystifications which had obscured those glories and progress to the future by drawing on the lessons of the old Nile valley philosophies.[4]

Diop’s influence was considerable; he was a politically active figure who contributed to restoring the African consciousness, which had been warped by slavery and colonialism. Diop had since his early days in Paris been politically active in the Rassemblement Democratique Africaine, highly active in politicizing the anti-colonial struggle, and in 1960, upon his return to Senegal, he continued what would be a life long political struggle.[5] Inspired by the efforts of Aimé Césaire[6] toward these ends, but not being a man of letters himself, Diop took up the call to rebuild the African personality from a strictly scientific, socio-historical perspective. He was keenly aware of the difficulties that such a scientific effort would entail and warned that "It was particularly necessary to avoid the pitfall of facility. It could seem too tempting to delude the masses engaged in a struggle for national independence by taking liberties with scientific truth, by unveiling a mythical, embellished past.” Diop believed that the political struggle for African independence would not succeed without acknowledging the civilizing role of the African people, dating from ancient Egypt. He singled out the contradiction of "the African historian who evades the problem of Egypt".

Diop supported his arguments with references to ancient authors such as Herodotus and Strabo. For example, when Herodotus wished to argue that the Colchian people were related to the Egyptians, he said that the Colchians were "black, with curly hair."[7] Diop used statements by these writers to illustrate his theory that the ancient Egyptians had the same physical traits as modern black Africans (skin colour, hair type). His interpretation of anthropological data (such as the role of matriarchy) and archaeological data led him to conclude that Egyptian culture was a Black African culture. In linguistics, he believed in particular that the Wolof language of contemporary West Africa is related to ancient Egyptian. Diop's arguments in favour of placing Egypt in the cultural and genetic context of Africa met a wide range of condemnation and rejection: mostly the seemingly felt need to split a localised Nile valley population arbitrarily into tribal or racial clusters. The often shaky scholarship was sometimes considered a form of racism in its turn, though Diop's early condemnation of European bias in his 1954 work Nations Nègres et Culture has been supported by later scholarship.[8] Diop's view that the scholarship of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century was based on a racist view of Africans was regarded as controversial when he expressed it from the 1950s until the early 1970s, as the field of African scholarship was still influenced by scientific racism.

The exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bern does not necessarily seek to re-evaluate the academic importance of Cheikh Anta Diop – that we leave to competent scholars –, but wants to shed light on a fascinating historical figure and thereby reflect on a specific ideological climate that pervaded 1960s Africa, a period when the notion of African cultural unity was formulated and promoted. This might be controversial, but the fact remains that Cheikh Anta Diop, having studied the human race's origins and pre-colonial African culture, is regarded as by far the most important figure in the development of “Afrocentric”[9] thought. Caught in the eye of a storm of controversy, Diop nevertheless opened up new paths of exploration, gave a new generation redemptive faith in its roots, and presented, if nothing else, a poetic image of greatness. In its daring, this dream of a lofty cradle of civilization may come closer to truth than the prosaic rebuttal of its critics, and as discoveries continue to be made, it proves itself more real than any dream. He is probably the only academic in the world who had a popular record album named in his honour: the Senegalese group Super Diamono titled one of their best-known LPs with Diop’s name after he had died; a fact that serves as an index of the scholar’s prominence and popularity.

We would like to thank Mohamed Ndiaye-Kingué and Vanessa Van Obberghen for their research in Dakar and for the preparation of the material featured in the exhibition.

[1] Valentin Yves Mudimbe, The Invention of Africa, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), 1988, p. 78

[2] See also: Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, a controversial three-volume work by Martin Bernal. Its subject matter is ancient Greece; the author's thesis regards the perception of ancient Greece in relation to its African and Asiatic neighbours by the West—Europe. Bernal alleges that a change in this Western perception took place from the 18th century onward and that this change fostered a subsequent denial by Western academia of any significant African and (western) Asiatic influences on ancient Greek culture. Black Athena had an enormous impact on African American Afrocentrist movements, because it offers a less Eurocentric theory of origin for western civilization. The book ignited a debate in the academic community. While some reviewers contend that studies of the origin of Greek civilization were tainted by a foundation of 19th century racism, many have criticised Bernal for the speculative nature of his hypothesis, his unsystematic and linguistically incompetent handling of etymologies as well as his naive analyses of ancient myth and historiography.

[3] Racial anthropology, pejoratively known as scientific racism, is the use of scientific, or ostensibly scientific, findings and methods to investigate differences among the human races, specifically in a historical context of ca. 1880 to 1930. As a term, scientific racism denotes the contemporary and historical scientific theories that employ anthropology (notably physical anthropology), anthropometry, craniometry, and other disciplines, in fabricating anthropologic typologies supporting the classification of human populations into physically discrete human races.

[4] Stephen Howe, Afrocentrism. Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes, (London-New York: Verso), 1998, pp. 165-166.

[5] Diop would in the course of over 25 years found three political parties that formed the major opposition in Senegal.

By 1962, Diop's party working on the basis of the ideas enumerated in his publication Black Africa: the economic and cultural basis for a federated state became a serious threat to the regime of then President Leopold Senghor. Diop was subsequently arrested and thrown in jail where he nearly died. The book expresses best Diop's political aims and objectives. He argues that only a united and federated African state will be able to overcome underdevelopment. This critical work constitutes a rational study of not only Africa's cultural, historical and geographical unity, but of Africa's potential for energy development and industrialization. Diop and other former members of his party continued their strong political activism, though president Senghor attempted to appease Diop by offering him and his supporters a certain number of government positions. Diop refused to enter into any negotiations until two conditions were met. The first, that all political prisoners be released, and the second that discussions be opened on government ideas and programs, not on the distribution of government posts. In protest to the refusal of the Senghor administration to release political prisoners, Diop remained largely absent from the political scene from 1966 to 1975.

[6] Aimé Fernand David Césaire (26 June 1913 – 17 April 2008) was an African-Martinican francophone poet, author and politician. He was one of the founders of the négritude movement in Francophone literature.

[7] Herodotus, History, Book II.

[8] Philip L Stein and Bruce M Rowe, Physical Anthropology, (McGraw-Hill), 2002, pp. 54-166

[9] Afrocentrism (also Afrocentricity; occasionally Africentrism) is an ethnocentric ideology which emphasizes the importance of African people, taken as a single group and often equated with black people, in culture, philosophy, and history. One might say that many significant ideas or claims put forward today by Afrocentrists were earlier expressed by Cheikh Anta Diop, though many have a much older, more diffuse ancestry. See: Stephen Howe, Afrocentrism. Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes, (London-New York: Verso), 1998, p. 163

CHEIKH ANTA DIOP

05.02. - 27.03.2011

This second exhibition in the project The idea of Africa (re-invented) is smaller in scale, less visual, more discursive, and indirectly tackles one of the most sensitive subjects: race. An anecdote has been lingering in my head since visiting Documenta XI in 2002, and maybe indirectly functioned as the impetus for this project. Strolling through the exhibition in Kassel, an acquaintance and colleague of mine could not withhold his irritation by his perception of the ubiquitous black body in the exhibition. It seemed as if in a strange way he considered a white body as neutral and normative in the context of an international exhibition. Or maybe his irritation arose because the black bodies in question were not contained in an exotic framework? I don’t know, but due to this fait-divers I was prompted to read a potentially involuntary subtext within Documenta XI, in the end an important element in the perception and the experience of an exhibition. Even if unintended, the exhibition provided an important shift of the gravity centre in the apparently still contested domain of skin colour in contemporary society, and it shed a clearer light on the preconceived assumptions under which a large scale exhibition like Documenta operates. Though the global orientation of Documenta XI focussed on how contemporary art in all its different forms can continue to develop in a dialectic relationship to the entirety of global culture, taking into account the current political, technological and ideological conflicts, developments and mixtures, it proved an extremely "difficult and sensitive" undertaking indeed. Decisive in the end was the breaking of taboos associated with the exhibition. The artistic director Okwui Enwezor cast doubt on Western culture’s claim to primacy by shifting, even inverting, the centres of development and the references to them.

The Idea of Africa (re-invented) is, as explained in the newspaper accompanying the first edition, inspired by the titles of two books by the Congolese philosopher Valentin Yves Mudimbe. Both trace how a certain “idea” of Africa was invented and constructed by the Western world from the Ancient Greeks until the 20th Century. Mudimbe also examines how African scholars who have worked within the limits of imposed language and epistemological frames ‘wrote back’. The exhibition-project at hand focuses on artistic and intellectual endeavours that trace another history, in which the ‘idea’ of Africa is not already a ‘given’ framed by the West.

Enter Senegalese historian, anthropologist, physicist and politician Cheikh Anta Diop (29 December 1923 in Thieytou, Diourbel Region - 7 February 1986 in Dakar). For Valentin Yves Mudimbe, Diop’s work on the cultural experiences of Africa is part of the most extreme examples of an ideological process set in motion by a group of African scholars in the 1950s: they made a distinction between “good” and “bad” works about Africa, according to their conception of the value of their own civilisation.[1] Diop’s ideas were formed early in his career and changed little thereafter. In lectures and articles in the early 1950s, he already proposed his main theses. Diop’s most controversial theory is of course that the Ancient Egyptians were Black Africans. By consequence, Western civilization, claiming to source itself in Ancient Greece – which was highly influenced by Egypt – would owe an enormous debt to a black civilization, an idea exorcised and shunned by the West from the 18th Century onwards.[2] The question of the race of ancient Egyptians was raised historically as a product of the scientific racism[3] of the 18th and 19th centuries. Since the second half of the 20th century, scholarly consensus has held that applying modern notions of race to ancient Egypt is anachronistic, but the debate has been revived in the popular domain of Afrocentric historiography and Black nationalism which tends to insist that Ancient Egypt was a "black civilization", with particular focus on the race of specific notable individuals from Dynastic times, including Tutankhamun, Cleopatra VII, and also the model for the Great Sphinx of Giza. For Diop this black Egyptian civilisation not only originated most important aspects of human social and intellectual development, but was also distinct from Eurasian societies in its matriarchal, spiritual, peaceable and humanistic character. Given that ancient Greece – and hence all European civilisation – was heavily influenced by this allegedly African Egyptian culture, Africa, Diop urged, must recover the glories of its ancient past, rejecting the colonial and racist mystifications which had obscured those glories and progress to the future by drawing on the lessons of the old Nile valley philosophies.[4]

Diop’s influence was considerable; he was a politically active figure who contributed to restoring the African consciousness, which had been warped by slavery and colonialism. Diop had since his early days in Paris been politically active in the Rassemblement Democratique Africaine, highly active in politicizing the anti-colonial struggle, and in 1960, upon his return to Senegal, he continued what would be a life long political struggle.[5] Inspired by the efforts of Aimé Césaire[6] toward these ends, but not being a man of letters himself, Diop took up the call to rebuild the African personality from a strictly scientific, socio-historical perspective. He was keenly aware of the difficulties that such a scientific effort would entail and warned that "It was particularly necessary to avoid the pitfall of facility. It could seem too tempting to delude the masses engaged in a struggle for national independence by taking liberties with scientific truth, by unveiling a mythical, embellished past.” Diop believed that the political struggle for African independence would not succeed without acknowledging the civilizing role of the African people, dating from ancient Egypt. He singled out the contradiction of "the African historian who evades the problem of Egypt".

Diop supported his arguments with references to ancient authors such as Herodotus and Strabo. For example, when Herodotus wished to argue that the Colchian people were related to the Egyptians, he said that the Colchians were "black, with curly hair."[7] Diop used statements by these writers to illustrate his theory that the ancient Egyptians had the same physical traits as modern black Africans (skin colour, hair type). His interpretation of anthropological data (such as the role of matriarchy) and archaeological data led him to conclude that Egyptian culture was a Black African culture. In linguistics, he believed in particular that the Wolof language of contemporary West Africa is related to ancient Egyptian. Diop's arguments in favour of placing Egypt in the cultural and genetic context of Africa met a wide range of condemnation and rejection: mostly the seemingly felt need to split a localised Nile valley population arbitrarily into tribal or racial clusters. The often shaky scholarship was sometimes considered a form of racism in its turn, though Diop's early condemnation of European bias in his 1954 work Nations Nègres et Culture has been supported by later scholarship.[8] Diop's view that the scholarship of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century was based on a racist view of Africans was regarded as controversial when he expressed it from the 1950s until the early 1970s, as the field of African scholarship was still influenced by scientific racism.

The exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bern does not necessarily seek to re-evaluate the academic importance of Cheikh Anta Diop – that we leave to competent scholars –, but wants to shed light on a fascinating historical figure and thereby reflect on a specific ideological climate that pervaded 1960s Africa, a period when the notion of African cultural unity was formulated and promoted. This might be controversial, but the fact remains that Cheikh Anta Diop, having studied the human race's origins and pre-colonial African culture, is regarded as by far the most important figure in the development of “Afrocentric”[9] thought. Caught in the eye of a storm of controversy, Diop nevertheless opened up new paths of exploration, gave a new generation redemptive faith in its roots, and presented, if nothing else, a poetic image of greatness. In its daring, this dream of a lofty cradle of civilization may come closer to truth than the prosaic rebuttal of its critics, and as discoveries continue to be made, it proves itself more real than any dream. He is probably the only academic in the world who had a popular record album named in his honour: the Senegalese group Super Diamono titled one of their best-known LPs with Diop’s name after he had died; a fact that serves as an index of the scholar’s prominence and popularity.

We would like to thank Mohamed Ndiaye-Kingué and Vanessa Van Obberghen for their research in Dakar and for the preparation of the material featured in the exhibition.

[1] Valentin Yves Mudimbe, The Invention of Africa, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), 1988, p. 78

[2] See also: Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, a controversial three-volume work by Martin Bernal. Its subject matter is ancient Greece; the author's thesis regards the perception of ancient Greece in relation to its African and Asiatic neighbours by the West—Europe. Bernal alleges that a change in this Western perception took place from the 18th century onward and that this change fostered a subsequent denial by Western academia of any significant African and (western) Asiatic influences on ancient Greek culture. Black Athena had an enormous impact on African American Afrocentrist movements, because it offers a less Eurocentric theory of origin for western civilization. The book ignited a debate in the academic community. While some reviewers contend that studies of the origin of Greek civilization were tainted by a foundation of 19th century racism, many have criticised Bernal for the speculative nature of his hypothesis, his unsystematic and linguistically incompetent handling of etymologies as well as his naive analyses of ancient myth and historiography.

[3] Racial anthropology, pejoratively known as scientific racism, is the use of scientific, or ostensibly scientific, findings and methods to investigate differences among the human races, specifically in a historical context of ca. 1880 to 1930. As a term, scientific racism denotes the contemporary and historical scientific theories that employ anthropology (notably physical anthropology), anthropometry, craniometry, and other disciplines, in fabricating anthropologic typologies supporting the classification of human populations into physically discrete human races.

[4] Stephen Howe, Afrocentrism. Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes, (London-New York: Verso), 1998, pp. 165-166.

[5] Diop would in the course of over 25 years found three political parties that formed the major opposition in Senegal.

By 1962, Diop's party working on the basis of the ideas enumerated in his publication Black Africa: the economic and cultural basis for a federated state became a serious threat to the regime of then President Leopold Senghor. Diop was subsequently arrested and thrown in jail where he nearly died. The book expresses best Diop's political aims and objectives. He argues that only a united and federated African state will be able to overcome underdevelopment. This critical work constitutes a rational study of not only Africa's cultural, historical and geographical unity, but of Africa's potential for energy development and industrialization. Diop and other former members of his party continued their strong political activism, though president Senghor attempted to appease Diop by offering him and his supporters a certain number of government positions. Diop refused to enter into any negotiations until two conditions were met. The first, that all political prisoners be released, and the second that discussions be opened on government ideas and programs, not on the distribution of government posts. In protest to the refusal of the Senghor administration to release political prisoners, Diop remained largely absent from the political scene from 1966 to 1975.

[6] Aimé Fernand David Césaire (26 June 1913 – 17 April 2008) was an African-Martinican francophone poet, author and politician. He was one of the founders of the négritude movement in Francophone literature.

[7] Herodotus, History, Book II.

[8] Philip L Stein and Bruce M Rowe, Physical Anthropology, (McGraw-Hill), 2002, pp. 54-166

[9] Afrocentrism (also Afrocentricity; occasionally Africentrism) is an ethnocentric ideology which emphasizes the importance of African people, taken as a single group and often equated with black people, in culture, philosophy, and history. One might say that many significant ideas or claims put forward today by Afrocentrists were earlier expressed by Cheikh Anta Diop, though many have a much older, more diffuse ancestry. See: Stephen Howe, Afrocentrism. Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes, (London-New York: Verso), 1998, p. 163